Royal Regalia: a Sword of the Last Sultan of Darfur, Ali Dinar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Muslim Sudan

Downloaded from Nile Basin Research Programme www.nile.uib.no through Bergen Open Research Archive http://bora.uib.no Trade and Wadis System(s) in Muslim Sudan Intisar Soghayroun Elzein Soghayroun FOUNTAIN PUBLISHERS Kampala Fountain Publishers P. O. Box 488 Kampala - Uganda E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.fountainpublishers.co.ug © Intisar Soghayroun Elzein Soghayroun 2010 First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-9970-25-005-9 Dedication This book is dedicated to my father: Soghayroun Elzein Soghayroun, with a tremendous debt of gratitude. iii Contents Dedication..................................................................................................... iiv List.of .Maps..................................................................................................vi List.of .plates..................................................................................................vii Preface.......................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgement.........................................................................................xiii 1 The Land, its People and History ...................................... 1 The Physiographic Features of the Country ......................................1 -

Ethnic Violence in Africa: Destructive Legacies of Pre-Colonial States

Ethnic Violence in Africa: Destructive Legacies of Pre-Colonial States Jack Paine* June 14, 2017 Abstract Despite endemic ethnic violence in post-colonial Africa, minimal research has analyzed historical causes of regional variance in civil wars and military coups. This paper argues that ethnic differences gained heightened political salience in countries with an ethnic group organized as a pre-colonial state (PCS). Combining this insight with a model on post-colonial rulers’ tradeoff between coups and civil wars implies PCS groups and other groups in their country should more frequently participate in ethnic violence. Regression evidence using original data on pre-colonial African states demonstrates that ethnic groups in countries with at least one PCS group have participated in either ethnic civil wars or coups more frequently than ethnic groups in other countries, with the modal type of violence for different groups mediated by how pre-colonial statehood affected ethnopolitical inclusion. Before 1989, 34 of 35 ethnic groups that participated in major civil wars belonged to countries with a PCS group. Keywords: African politics, Civil war, Coup d’etat, Ethnic politics, Historical statehood *Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester, [email protected]. The author thanks Leo Arriola, Kyle Beardsley, Ernesto dal Bo, Mark Dincecco, Thad Dunning, Erica Frantz, Anderson Frey, Bethany Lacina, Alex Lee, Peter Lorentzen, Robert Powell, Philip Roessler, Erin Troland, Tore Wig, and seminar participants at UC Berkeley, University of Rochester, WGAPE 2015 hosted at the University of Washington, SPSA 2016, and WPSA 2017. Political violence such as civil wars and military coups has plagued Sub-Saharan Africa (henceforth, “Africa”) since independence, causing millions of battle deaths and contributing substantially to the region’s poor overall economic performance. -

Darfur: in Search of Peace Exploring Viable Solutions to the Darfur Crisis

human rights & human welfare a forum for works in progress working paper no. 50 Darfur: In Search of Peace Exploring Viable Solutions to the Darfur Crisis Prepared and Presented by: Dr. George Shepherd Dr. Peter Van Arsdale Negin Sobhani Nicole Tanner Frederick Agyeman‐Duah Please direct all feedback to: [email protected] Posted on 5 January 2009 http://www.du.edu/korbel/hrhw/working/2009/50‐ATADarfur‐2009.pdf © Africa Today Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. This paper may be freely circulated in electronic or hard copy provided it is not modified in any way, the rights of the author not infringed, and the paper is not quoted or cited without express permission of the author. The editors cannot guarantee a stable URL for any paper posted here, nor will they be responsible for notifying others if the URL is changed or the paper is taken off the site. Electronic copies of this paper may not be posted on any other website without express permission of the author. The posting of this paper on the hrhw working papers website does not constitute any position of opinion or judgment about the contents, arguments or claims made in the paper by the editors. For more information about the hrhw working papers series or website, please visit the site online at http://www.du.edu/gsis/hrhw/working Darfur: In Search of Peace 2 DDAARRFFUURR:: IINN SSEEAARRCCHH OOFF PPEEAACCEE EExxpplloorriinngg VViiaabbllee SSoolluuttiioonnss ttoo tthhee DDaarrffuurr CCrriissiiss REPORT OF A CONSULTATION HELD IN NAIROBI, KENYA, EAST AFRICA JUNE 911, 2008 PREPARED & PRESENTED BY: Dr. -

SWASTIKA the Pattern and Ideogram of Ideogram and Pattern The

Principal Investigators Exploring Prof. V. N. Giri the pattern and ideogram of Prof. Suhita Chopra Chatterjee Prof. Pallab Dasgupta Prof. Narayan C. Nayak Prof. Priyadarshi Patnaik pattern and ideogram of Prof. Aurobindo Routray SWASTIKA Prof. Arindam Basu Prof. William K. Mohanty Prof. Probal Sengupta Exploring the A universal principle Prof. Abhijit Mukherjee & of sustainability Prof. Joy Sen SWASTIKA of sustainability A universal principle SandHI INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR The Science & Heritage Initiative www.iitkgpsandhi.org INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR Exploring the pattern and ideogram of SWASTIKA A universal principle of sustainability SandHI The Science & Heritage Initiative INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR ii iii Advisor Prof. Partha P. Chakrabarti Director, IIT Kharagpur Monitoring Cell Prof. Sunando DasGupta Dean, Sponsored Research and Industrial Consultancy, IIT Kharagpur Prof. Pallab Dasgupta Associate Dean, Sponsored Research and Industrial Consultancy, IIT Kharagpur Principal Investigator (overall) Prof. Joy Sen Department of Architecture & Regional Planning, IIT Kharagpur Vide order no. F. NO. 4-26/2013-TS-1, Dt. 19-11-2013 (36 months w.e.f 15-1-2014 and 1 additional year for outreach programs) Professor-in-Charge, Documentation and Dissemination Prof. Priyadarshi Patnaik Department of Humanities & Social Sciences, IIT Kharagpur Research Scholars Group (Coordinators) Sunny Bansal, Vidhu Pandey, Tanima Bhattacharya, Shreyas P. Bharule, Shivangi S. Parmar, Mouli Majumdar, Arpan Paul, Deepanjan Saha, Suparna Dasgupta, Prerna Mandal Key Graphics Support Tanima Bhattacharya, Research Scholar, IIT Kharagpur Exploring ISBN: 978-93-80813-42-4 the pattern and ideogram of © SandHI A Science and Heritage Initiative, IIT Kharagpur Sponsored by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, Government of India Published in July 2016 SWASTIKA www.iitkgpsandhi.org A universal principle Design & Printed by Cygnus Advertising (India) Pvt. -

Egyptian Rule in the Sudan

SOME SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF TURKO - EGYPTIAN RULE IN THE SUDAN GABRIEL R. WARBURG Between 1821 and 1885 most of the area constituting the present Su- dan came under Turko-Egyptian rule. The annexation of the Sudan to Egypt was undertaken in 1820-1 by Muhammad `Ali, the Ottoman Vali of Egypt, and was completed under his grandson, the Khedive Ismacil, who extended this rule to the Great Lakes in the south and to Bahr al- Ghazal and Darfur in the west. In the history of the Sudan, this period became known as the (first) Turkiyya. The term Turkiyya is not really ar- bitrary since Egypt was itself an Ottoman province, ruled by an Ottoman (Albanian) dynasty. Moreover, most of the high officials and army officers serving in the Sudan were of Ottoman rather than Egyptian origin. Last- ly, though Arabic made considerable headway during the second half of the century in daily administrative usage, the senior officers and off~ cials continued to communicate in Turkish, since their superior- the Khedive - was a Turk and Turkish was the language of the ruling elite. Hence, when the Mahdist revolt errupted in June 1881, its main enemy were the Turks who had oppressed the Sudanese and had - according to the Mahdi - corrupted Islam. a. European Historical and other Writings on N~ neteenth-Century Sudan Until the second half of the twentieth century western views both on Turkish rule in the Sudan as well as on the Mahdiyya, were largely based on the writings of European trades, explorers and soldiers of for- tune. -

SARS SN15 Mcgregor Opt.Pdf

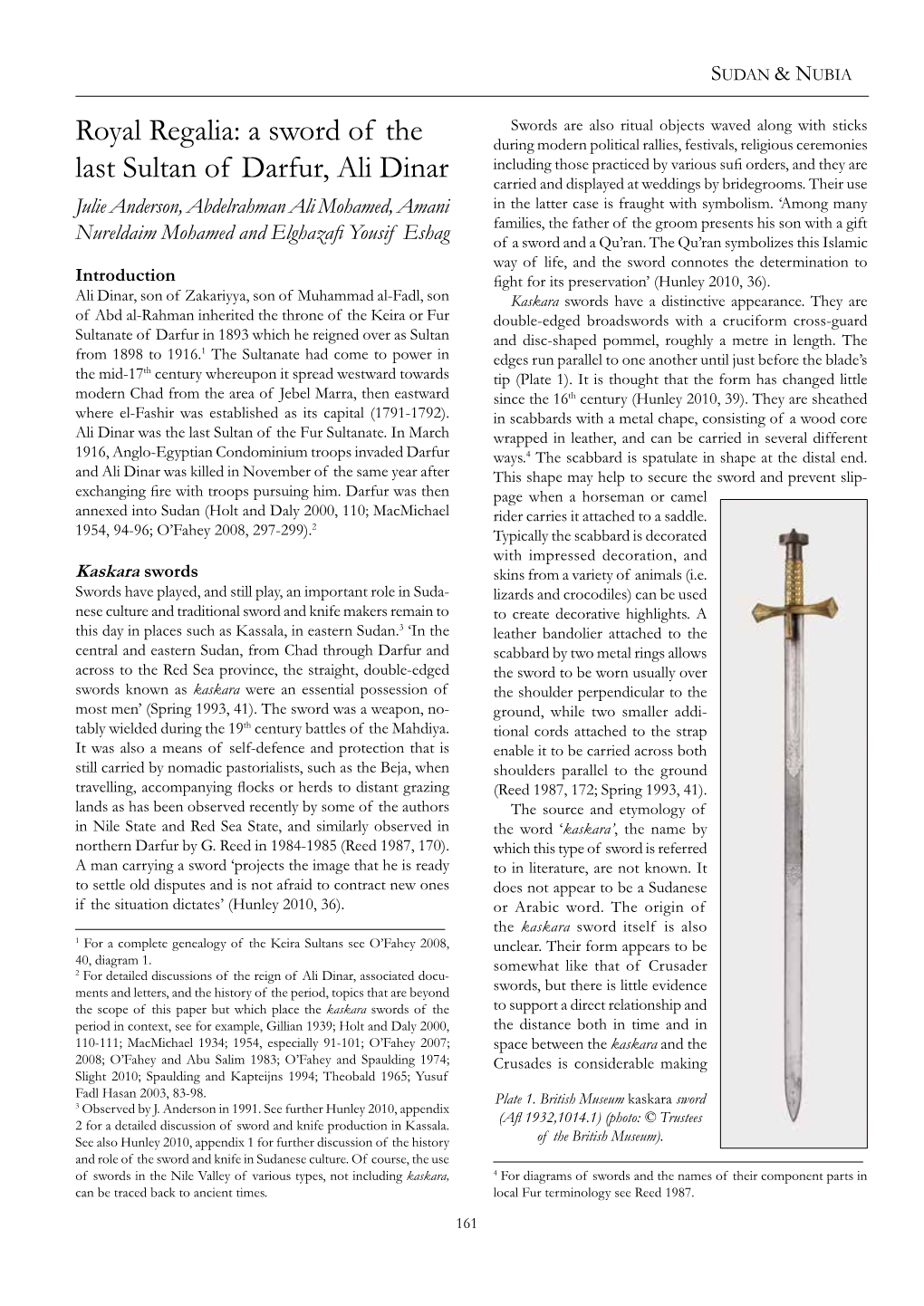

1 2 S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 15 2011 Contents The Sudan Archaeological Research Society – 2 A Meroitic offering table from Maharraka - 105 An Anniversary Tribute Found, recorded, lost or not? William Y. Adams Jochen Hallof Early Makuria Research Project. Excavations at ez-Zuma. The Third Season, 108 The Kirwan Memorial Lecture Jan.-Feb. 2009 Mahmoud el-Tayeb and Ewa Czyżewska Qasr Ibrim: The last 3000 years 3 Pamela J. Rose Report on burial architecture of tumuli T. 11 119 and T. 13 Katarzyna Juszczyk Reports A preliminary report on mortuary practices and 124 social hierarchy in Akad cemetery Neolithic beakers from North-Eastern Africa 13 Mohamed Faroug Abd el-Rahman Anna Longa Palaces in the Mountains: An Introduction to the 129 Pottery from Sites Surveyed in Sodari District, 18 Archaeological Heritage of the Sultanate of Darfur Kordofan Province. An Interim Report 2008-2009 Andrew McGregor Howeida M. Adam and Abdelrahim M. Khabir The archaeological and cultural survey of the Dongola 142 The early New Kingdom at Sai Island: preliminary 23 Reach, west bank from el-Khandaq to Hannek: results based on the pottery analysis (4th Season 2010) Survey Analysis Julia Budka Intisar Soghayroun Elzein Sesebi 2011 34 Kate Spence, Pamela J. Rose, Rebecca Bradshaw, Pieter Collet, Amal Hassan, John MacGinnis, Aurélia Masson Miscellaneous and Paul van Pelt The 10th-9th century BC – New Evidence from the 39 Obituary Cemetery C of Amara West John A. Alexander (1922-2010) 146 Michaela Binder Pamela J. Rose Excavations at Kawa, 2009-10 54 Book reviews Derek A. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Some Aspects of Turco-African Relations with Special

Some aspects of Tu rco-African Relations with special reference to the Sudan Yusuf Fadl Hasan Introduction Turkey’s relation with Africa is old, it goes back to the sixteenth century. It had developed political, cultural and economic relations with the Arab North African countries, the Nilotic Sudan and some strategic parts in East Africa. There was no significant presence or relation with Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the religious bond linked nearly all-African Muslims especially those of Bilad al-Sudan and North-East Africa with the Ottoman Caliphate – the Servitor of the Two Holy Places – Mecca and Medina is of great signifi- cance. Although the Sudan is an Afro-Arab country, much influenced by the Ottoman Empire, like other Arab countries, I am considering it in this paper as a Sub-Saharan African country. Africa with its vast resources now represents the world new Economic Frontier and hence it is laid open to tough competition among the highly developed nations. Mighty in civilization, well armed as a regional power and equipped with the characteristic of a modern state. Turkey aims at developing its relations with the African continent. In 1998, an Action Plan of the Turkish Foreign Policy of Opening Up to Africa was initiated. On 21st, September 2005. H. E. Mr. Abdullah Gül, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, of the Republic of Turkey, in his speech to the 60th session of United Nations General Assembly states: “We attach great importance to fur- thering our relations and cooperation with the African Continent. According to an Action plan Turkey is vigorously developing its relations with Africa as a whole. -

Georgetown University-SFS-Q Research Seminar Anthropology of War and Peace in Darfur ANTH 305-1 August 21-Nov.27, 2017 Fall 2017

Georgetown University-SFS-Q Research Seminar Anthropology of War and Peace in Darfur ANTH 305-1 August 21-Nov.27, 2017 Fall 2017 Instructor Rogaia Mustafa Abusharaf Office Number 0D-55 Office Hours Monday & Wednesday: By Appointment 1 Doyle Seminar This course is a Doyle Seminar, part of the Doyle Engaging Difference Program, a new campus- wide curricular initiative, and gives faculty the opportunity to enhance the student research component of upper-level seminars that address questions of national, social, cultural, religious, moral, and other forms of difference. The Doyle seminars are intended to deepen student learning about diversity and difference through enhanced research opportunities, interaction with thought leaders, and dialogue with the Georgetown community and beyond. Description Generations of travelers, historians, ethnographers, colonial administrators, humanitarian workers, celebrities, and NGO personnel have produced an enormous amount of knowledge about the Darfur. This course draws upon illustrative examples from the earliest forms of travel writing to the most recent forms of digital activism. Although recent events around the world have managed to divert attention from Darfur, its significance in international politics continued since the arrest warrant was issued for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1593, concerning genocide and war crimes in Darfur. The United Nations Security Council referred the case to Luis Moreno-Ocampo, former prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, after the investigation of Sudan's own special prosecutor had not led to war prosecutions, suggesting the failure of institutions of justice within the country. Events of this magnitude are to be expected given the pervasive political violence that engulfed the country following its independence from British rule in January 1956. -

Ibn Dayfulla's Tabaqat

Ibn Dayfulla’s Tabaqat: An Analysis of Proto- National Identity under the Funj Sultanate in the North-Central Sudan (1504 – 1821) By Waad I. Adam Mentored by Dr. Karine V. Walther Reader: Mohammad Riza Pirbhai April 17th, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of Honors in Culture and Politics, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service in Qatar, Georgetown University, Spring 2014. Waad Adam Table of Contents Introduction Setting the Stage …………………………………………………………………… 2 Thesis Question …………………………………………………………………… 3 Background on the Funj Sultanate ………………………………………………. 5 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………….. 9 Methodology ……………………………………………………………………….. 19 Chapter I – Religion in the Tabaqat ................................................................. 23 Religion and Theories of Nationalism ……………………………………......... 23 History of Islamization of the Sudan …………………………………………… 26 Analysis of Tabaqat ………………………………………………………………. 31 Chapter II – Language in the Tabaqat ………………………………………… 35 Language and Theories of Nationalism ………………………………………... 37 History of Arabization of the Sudan …………………………………………… 39 Analysis of Tabaqat ………………………………………………………………. 43 Chapter III – Genealogy in the Tabaqat ……………………………………… 52 Genealogy and Theories of Nationalism ……………………………………….. 53 History of Arab Genealogy in the Sudan ……………………………………… 57 Analysis of Tabaqat ………………………………………………………………. 61 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………… 66 1 Waad Adam Introduction In October 1966, Saddiq el-Mahdi, the former prime minister and -

Charity and Commercial Success As Vectors of Asymmetry and Inequality: the Unconceptualised Elements of Development in Islamist Sudan During the First Republic

chapter �� Charity and Commercial Success as Vectors of Asymmetry and Inequality: The Unconceptualised Elements of Development in Islamist Sudan during the First Republic Raphaëlle Chevrillon-Guibert Abstract The Sudanese Islamist experiment is far from having put an end to the conflict-ridden history of the country, despite the South achieving independence in July 2011. How- ever, a higher degree of regional integration outside the South was one of the stated aims of the Islamists when they came to power in 1989. This chapter will investigate the apparent paradox by exploring the experiments in development undertaken by Sudanese Islamists during their first republic (1989–2011) on the basis of the study of certain social practices they actively encouraged, namely evergetism and philanthro- py. It is based on an analysis of the charitable practices carried out by the main traders in the Sudanese capital’s principal market during the Islamist regime. The regional— more specifically Darfurian—origin of most of these main traders makes it possible to compare what these practices produce in each different territory. The chapter shows that this encouragement, which is not part of any specific plan thought up by the Is- lamists, leads to different forms of development that vary depending on the local and human contexts in which the actors live, and also the way they conceive their roles within in the circles to which they belong. It then highlights how these variations pro- duce extremely disparate and often conflict-ridden results, which ultimately pursue the asymmetric formation of the Sudanese state, prolonging a historical trajectory that has produced injustice and generated conflict (Figure 11.1). -

DARFUR HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS: a CATALOGUE by R.S. O'fahey

1 DARFUR HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS: A CATALOGUE by R.S. O’Fahey University of Bergen Bergen 2006 2 Dedicated to the memory of my friend and mentor The late Dr. Mu˛ammad Ibrhım Abü Salım (1927-2004) & to the memory of the brothers, al-‡ayyib and Ibrhım Mu˛ammad al-Nür, Fulani merchants and scholars who made this collection possible through their material generosity, but, more importantly, who through their generosity of spirit, scholarship and understanding 3 CONTENTS Note to the Second Edition The Sultans of Darfur Introduction to the First Version (March 1981) The Catalogue: DF1.1.1 to DF380.60/8 Index of Archives Bibliography 4 NOTE TO THE SECOND EDITION The present work is a revised and extended version of the first catalogue, made as a typescript for limited circulation under a similar title in March 1981.1 This version is intended as source-book to my ongoing project to lay out and make available the sources on the customary and sultanic law of Darfur.2 The next stage will be the publication of my notes on the same topic from the Condominium sources. A third stage, which will have to involve lawyers from Darfur, will be to extract from this body of material some general principles to act as guidelines for the redistribution of land in the province. Thus my purpose in preparing this second version of the Catalogue is far from purely academic; the issue of land is a vital, contentious and fundamental issue in the ongoing conflict in Darfur, as I have discovered working as a consultant to the UN Mission to the Sudan (UNMIS) and the African Union (AU) over the last year.