The Dickensian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

25 December 2020 Page 1 of 3

BBC 4 Listings for 19 – 25 December 2020 Page 1 of 3 SATURDAY 19 DECEMBER 2020 beyond including all the big hits, rare 60s performances from SUN 23:00 Soul Noel: Gospel and Soul Stars Sing European TV, including a stunning I Started a Joke, a rarely Christmas (b00wvcs3) SAT 19:00 The Two Ronnies Sketchbook (b007cdzh) seen Top of the Pops performance of World, the big hits of the A Christmas concert with a difference, as carols, Christmas Christmas 70s and some late performances from the 90s, with the brothers anthems and the odd pop classic are performed with a gospel Gibb in perfect harmony. and soul twist. Back again for one very last extra special Christmas outing, the Two Ronnies bring you their favourite treats from their many Warm yourself on a winter's night with gospel, soul, reggae, ska classic Christmas shows. Look out for The Milkman's SAT 00:30 Disco at the BBC (b01cqt74) and soca versions of classics such as Silent Night, Hark the Christmas Message, Christmas Day in the Yukon and a lavish A foot-stomping return to the BBC vaults of Top of the Pops, Herald Angels Sing, Jingle Bells, God Rest Ye Merry interpretation of Alice through the Looking Glass - Ronnies The Old Grey Whistle Test and Later with Jools as the Gentlemen and many more. style. Music comes courtesy of Katie Melua singing Have programme spins itself to a time when disco ruled the floor, the Yourself a Merry Little Christmas. airwaves and our minds. The visual floorfillers include classics Filmed at the Porchester Hall in west London, it features UK from luminaries such as Chic, Labelle and Rose Royce to glitter soul diva Beverley Knight, the multi- talented jazz blues soul ball surprises by The Village People. -

Appendix: Street Plans

Appendix: Street Plans Charles Dickens' birthplace. (Michael Allen) 113 114 Appendix The Hawke Street area as it is now, showing the site of number 16. (Michael Allen) Appendix 115 The Wish Street area as it is now, showing the site of the house occupied by the Dickens family. (Michael Allen) 116 Appendix Cleveland Street as it is now, showing the site of what was 10 Norfolk Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 117 Site of 2 Ordnance Terrace. (Michael Allen) 118 Appendix Site of 18 StMary's Place, The Brook. (Michael Allen) Appendix 119 Site of Giles' House, Best Street. (Michael Allen) 120 Appendix Site of 16 Bayham Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 121 Site of 4 Gower Street North. (Michael Allen) 122 Appendix Site of 37 Little College Street. (Michael Allen) Appendix 123 "'2 ~ <( Qj ftl ~ 0 ~ a; .......Q) ....... en ...., c .. ftl ...-' .. 0 ~ -....Q) .. u; 124 Appendix Site of 29 Johnson Street. (Michael Allen) Notes The place of publication is London unless otherwise stated. INTRODUCTION 1. 'Dickens's obscure childhood in pre-Forster biography', by Elliot Engel, in The Dickensian, 1976, pp. 3-12. 2. The letters of Charles Dickens, Pilgrim edition, Vol. 1: 1820-1839 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965) p. 423. 3. In History, xlvii, no. 159, pp. 42-5. 4. The Pickwick Papers (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) p. 521. 5. John Forster, The life of Charles Dickens (Chapman & Hall, 1872-4) Vol. 3, p. 11. 6. Ibid., Vol. 1, p. 17. 1 PORTSMOUTH 1. Gladys Storey, Dickens and daughter (Muller, 1939) p. 31. 2, 'The Dickens ancestry: some new discoveries', in The Dickensian, 1949, pp. -

Textileartscouncil William Morrisbibliography V2

TAC Virtual Travels: The Arts and Crafts Heritage of William and May Morris, August 2020 Bibliography Compiled by Ellin Klor, Textile Arts Council Board. ([email protected]) William Morris and Morris & Co. 1. Sites A. Standen House East Grinstead, (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/standen-house-and-garden/features/discover-the- house-and-collections-at-standen Arts and Crafts family home with Morris & Co. interiors, set in a beautiful hillside garden. Designed by Philip Webb, taking inspiration from the local Sussex vernacular, and furnished by Morris & Co., Standen was the Beales’ country retreat from 1894. 1. Heni Talks- “William Morris: Useful Beauty in the Home” https://henitalks.com/talks/william-morris-useful-beauty/ A combination exploration of William Morris and the origins of the Arts & Crafts movement and tour of Standen House as the focus by art historian Abigail Harrison Moore. a. Bio of Dr. Harrison Moore- https://theconversation.com/profiles/abigail- harrison-moore-121445 B. Kelmscott Manor, Lechlade - Managed by the London Society of Antiquaries. https://www.sal.org.uk/kelmscott-manor/ Closed through 2020 for restoration. C. Red House, Bexleyheath - (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/red-house/history-at-red-house When Morris and Webb designed Red House and eschewed all unnecessary decoration, instead choosing to champion utility of design, they gave expression to what would become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris’ work as both a designer and a socialist were intrinsically linked, as the creation of the Arts and Crafts Movement attests. D. William Morris Gallery - Lloyd Park, Forest Road, Walthamstow, London, E17 https://www.wmgallery.org.uk/ From 1848 to 1856, the house was the family home of William Morris (1834-1896), the designer, craftsman, writer, conservationist and socialist. -

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

Various Locations in England Including Pip's Home in Kent, a Cemetery On

1. SETTING: Various locations in England including Pip’s home in Kent, a cemetery on the marshes, Miss Havisham’s estate a.k.a. Satis House, Joe Gargery’s forge, and Pip’s rooms in London. The time flows between the years 1812 and 1840. AT RISE: The ruined gardens of Satis House, 1840. ACTORS #3, #4, #5, and #6 enter. They look around the garden in wonder, then take the positions they will assume at play’s end. PIP enters and looks around at the disaster of what was once a grand estate. After a moment… PIP (To audience) My name is Philip Pirrip, but ever since I was a young lad I was known as… ACTOR #4 Pip… ACTOR #5 Pip… ACTOR #6 Pip… ACTOR #3 Pip… (ESTELLA enters.) ESTELLA Hello, Pip. (PIP turns to her, surprised. He takes a step towards her.) PIP Estella! (ESTELLA, ACTOR #6, and ACTOR #5 twirl off.) 2. PIP (cont.) (To audience) At the age of two I was orphaned, and was taken in by my brother-in-law, a kind-hearted blacksmith named Joe Gargery… (ACTOR # 4 steps forward and becomes JOE.) …and his wife, my much older sister, whom I have always referred to as “Mrs. Joe.” (ACTOR #3 steps forward and becomes MRS. JOE.) Mrs. Joe resented my presence in her household. MRS. JOE I did and I do and I don’t deny it. Left with a child such as this to raise up… (She shakes PIP.) Lazy and useless, that’s what you are! A trial to my very soul! JOE Now, there’s no need for that. -

Charles Dickens Unit Study

Charles Dickens Unit Study Subjects: Reading, History, Writing, Math, Following Directions, Geography ©2019 Randi Smith www.peanutbutterfishlessons.com Teacher Instructions Thank you for downloading our Charles Dickens Unit Study! It was created to be used with the books: Magic Tree House: A Ghost Tale for Christmas Time and Who Was Charles Dickens?. You may incorporate other books about Charles Dickens, as well. Here is what is included in the study: Pages 3-10: Facts about Charles Dickens Notetaking Sheets: Use with Who Was…? Contains answer key. Pages 11-12: Facts about Charles Dickens Notetaking Sheets Short Version: Use with MTH. Contains answer key. Pages 13-16: Timeline of Charles Dickens’ Life: Students may write on timeline or cut and glue events provided. Page 17: Writing Prompt: Diary Entry of one of Dickens’ characters. Page 18: Scrambled Words Page 19: Compare and Contrast: Two of Dickens’ characters Pages 20-21: British Money Activity Page 22: Answer Key for Scrambled Words and Money Activity Pages 23-24: Following Directions in London with map. Also refer to our post: Charles Dickens FREE Unit Study for: 1. A list of some of his popular books and movies that are appropriate for children. 2. Videos to learn more about Charles Dickens 3. Links to other resources such as a Virtual Tour of the Charles Dickens Museum and A Christmas Carol FREE Unit Study. You May Also Be © Interested In: 2019 Credits www.peanutbutterfishlessons.com Smith Randi Frames by: Map Clip Art by: Facts about Charles Dickens Birth (date and place): _____________________________ -

Charles' Childhood

Charles’ Childhood His Childhood Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812 in Portsmouth. His parents were John and Elizabeth Dickens. Charles was the second of their eight children . John was a clerk in a payroll office of the navy. He and Elizabeth were an outgoing, social couple. They loved parties, dinners and family functions. In fact, Elizabeth attended a ball on the night that she gave birth to Charles. Mary Weller was an early influence on Charles. She was hired to care for the Dickens children. Her bedtime stories, stories she swore were quite true, featured people like Captain Murder who would make pies of out his wives. Young Charles Dickens Finances were a constant concern for the family. The costs of entertaining along with the expenses of having a large family were too much for John's salary. In fact, when Charles was just four months old the family moved to a smaller home to cut expenses. At a very young age, despite his family's financial situation, Charles dreamed of becoming a gentleman. However when he was 12 it looked like his dreams would never come true. John Dickens was arrested and sent to jail for failure to pay a debt. Also, Charles was sent to work in a shoe-polish factory. (While employed there he met Bob Fagin. Charles later used the name in Oliver Twist.) Charles was deeply marked by these experiences. He rarely spoke of this time of his life. Luckily the situation improved within a year. Charles was released from his duties at the factory and his father was released from jail. -

Broadstairs Dickens Fellowship Newsletter March 2021

BROADSTAIRS DICKENS FELLOWSHIP NEWSLETTER MARCH 2021 NSPCC/DICKENS FELLOWSHIP BROADSTAIRS We are delighted to announce that the reading of A Christmas Carol performed by the Dickens Declaimers from Broadstairs raised a total of £1400 for the NSPCC over the Christmas period. The NSPCC have issued this certificate and we, like the charity, are delighted with the result. A big thank you to everyone out there who donated. It’s much appreciated. The Mystery of Charles Dickens by A.N. Wilson Published by Atlantic Books (Paperback edition out in June 2021, £9.99) BOOK REVIEWS A.N.Wilson asserts that Dickens “was a man of masks, who probably never revealed himself to anyone; quite conceivably, he did not reveal himself to himself.” So he undertakes to find the hidden mysteries behind these masks, the events in his life that have formed the man and the writer. One such which was unacknowledged by Dickens at the time (though well-known to us nowadays) was his childhood work at Warren’s Blacking Factory after his fantasist father had been condemned to the Marshalsea for debt. This dreadful experience of abandonment and poverty marked him for life and appeared in his novels in the guise of David Copperfield and Oliver Twist. He blamed his mother more than his father, channelling her into so many of his foolish women characters, whereas his feckless father becomes the affectionate and resilient Micawber. This flawed relationship with his mother probably soured his relationship with his wife, Catherine. It is part of the solution to the mystery of how a man so imbued with pity for humanity could be so cruel to his wife. -

Magwitch's Revenge on Society in Great Expectations

Magwitch’s Revenge on Society in Great Expectations Kyoko Yamamoto Introduction By the light of torches, we saw the black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud of the shore, like a wicked Noah’s ark. Cribbed and barred and moored by massive rusty chains, the prison-ship seemed in my young eyes to be ironed like the prisoners (Chapter 5, p.34). The sight of the Hulk is one of the most impressive scenes in Great Expectations. Magwitch, a convict, who was destined to meet Pip at the churchyard, was dragged back by a surgeon and solders to the hulk floating on the Thames. Pip and Joe kept a close watch on it. Magwitch spent some days in his hulk and then was sent to New South Wales as a convict sentenced to life transportation. He decided to work hard and make Pip a gentleman in return for the kindness offered to him by this little boy. He devoted himself to hard work at New South Wales, and eventually made a fortune. Magwitch’s life is full of enigma. We do not know much about how he went through the hardships in the hulk and at NSW. What were his difficulties to make money? And again, could it be possible that a convict transported for life to Australia might succeed in life and come back to his homeland? To make the matter more complicated, he, with his money, wants to make Pip a gentleman, a mere apprentice to a blacksmith, partly as a kind of revenge on society which has continuously looked down upon a wretched convict. -

Pip's Ego Oscillations in Charles Dickens's Great Expectations

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume 5, Number 1. February 2021 Pp.262 -278 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol5no1.19 Pip's Ego Oscillations in Charles Dickens's Great Expectations Bechir Saoudi English Department, College of Science and Humanities, Hotat Bani Tamim, Prince Sattam Bin AbdulAziz University, Al-Kharj, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia English Department, ISEAH, Kef, Jendouba University, Tunisia Correspondent Author: [email protected] Lama Fahad Al-Eid English Department, College of Science and Humanities, Hotat Bani Tamim, Prince Sattam Bin AbdulAziz University, Al-Kharj, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Noura Mohammed Al-Break English Department, College of Science and Humanities, Hotat Bani Tamim, Prince Sattam Bin AbdulAziz University, Al-Kharj, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Rahaf Saad Al-Samih English Department, College of Science and Humanities, Hotat Bani Tamim, Prince Sattam Bin AbdulAziz University, Al-Kharj, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Tarfah Abdullah Al-Hammad English Department, College of Science and Humanities, Hotat Bani Tamim, Prince Sattam Bin AbdulAziz University, Al-Kharj, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Received: 12/10/ 2020 Accepted: 2/2/2021 Published: 2/24/2021 Abstract This research project studies Pip's ego fluctuations in Charles Dickens's Great Expectations. Freud's division of the human psyche into id, ego and superego is appropriate for the analysis of the rise and fall of the hero in his pursuit to attain gentlemanhood. Four main questions have been addressed: First, what makes up Pip's id? Second, what are the main components of his superego? Third, does Pip's ego succeed or fail in striking a balance between his id and superego? In what ways does it fail? And fourth, how does Pip's ego eventually succeed in striking a balance between his id and superego? The study finds out that Pip's id is demonstrated through his fascination with high-class lifestyle and relinquishment of common life. -

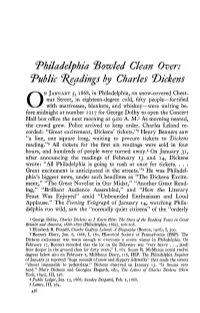

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP). -

The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XI

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen's University Research Portal The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XI Litvack, L. (2009). The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XI. The Dickensian, 105 (1), 36-53. Published in: The Dickensian Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:15. Feb. 2017 1 The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XI References (at the top left of each entry) to the earlier volumes of the British Academy-Pilgrim edition of The Letters of Charles Dickens are by volume, page and line, every printed line below the running head being counted. Where appropriate, note and column number are included. Dickens letters continue to come in and at least a further four Supplements are anticipated. The editors gratefully acknowledge the help of the following individuals and institutions: Christine Alexander; Biblioteca Berio, Genoa; Dan Calinescu; the late Richard Davies; Ray Dubberke; Eamon Dyas and Nicholas Mays (Times Newspapers Limited Archive, News International Limited); Andrew Lambert (King’s College, University of London); Paul Lewis; David McClay and Rachel Thomas (National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh); Alastair J.