12 Prof. Penelope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

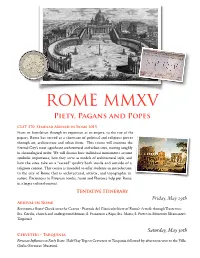

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

VERGIL in VROMA: Exploring the Capitoline Hill

VERGIL IN VROMA: Exploring the Capitoline Hill Goals: 1. Practice methods of navigation and conversation in the MOO 2. Explore some of the educational resources in VRoma 3. Use virtual space to come to a better understanding of Roman culture and civilization through group discussion of issues surrounding a selected site. 4. Enhance understanding and appreciation of the Aeneid through exploring the epic’s connections with the city of Rome. Worksheets: 1. Quick Start Guide to the VRoma Learning Environment 2. Group Site Assignment General Instructions: Explore your assigned site completely, visiting all its rooms and examining its varied contents, including texts, objects, bots, and links Read your Site Assignment through carefully to be clear about the topics you are asked to discuss. When you have completed the assignment, save your HTML Chat Log and email a copy of it to your professor. Site Assignment: Teleport to the site by typing @go Capitoline 1. Read the materials there to get a sense of the geography and topography of the area. Why did this hill come to have such symbolic power for the Romans? Compare and contrast the use that Ovid and Horace make of this symbolism. What does Vergil use instead of the hill itself to symbolize Rome's ability to endure and prevail? 2. Then using the exit links at the bottom of the screen, move to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and read about its structure, divinities, and history. What was unusual about this temple in comparison with the newer temples being built by Augustus, and why didn't the Romans want to change its structure? What links does the Jupiter in this temple have with the god portrayed by Vergil? What about the Juno in this temple? As protectress of Rome, she is certainly different from Vergil's goddess. -

2010 NJCL Ancient Geography Test

Contest ID 1018 2010 NJCL Ancient Geography Test Identify the following locations from the map of Italy (page 6 of this test): 1. Rome A. 17 B. 21 C. 25 D. 27 2. Brundisium A. 6 B. 7 C. 8 D. 9 3. Ostia A. 17 B. 22 C. 24 D. 25 4. Liguria A. 28 B. 29 C. 31 D. 32 5. Croton A. 2 B. 5 C. 6 D. 25 6. Naples A. 23 B. 24 C. 25 D. 26 7. Syracuse A. 1 B. 2 C. 4 D. 6 8. Milan A. 15 B. 16 C. 18 D. 19 9. Aquilea A. 10 B. 12 C. 16 D. 18 10. Illyricum A. 28 B. 29 C. 31 D. 32 11. Ravenna A. 10 B. 11 C. 13 D. 15 12. Mt. Etna A. 1 B. 2 C. 3 D. 4 13. Pisa A. 15 B. 17 C. 21 D. 25 14. Capua A. 6 B. 23 C. 24 D. 27 15. Eryx A. 1 B. 3 C. 9 D. 25 Identify the following locations from the map of Greece (page 7 of this test): 16. Athens A. 8 B. 13 C. 14 D. 16 17. Sparta A. 2 B. 4 C. 5 D. 11 18. Thebes A. 1 B. 11 C. 15 D. 17 19. Troy A. 22 B. 23 C. 24 D. 26 20. Corinth A. 1 B. 6 C. 8 D. 10 2010 NJCL Ancient Geography, Page 1 21. Knossus A. 2 B. 4 C. 27 D. 28 22. Epidaurus A. 6 B. 8 C. -

The Hidden Father, Francesco Albertini.Pdf

C.PP.S. Resource Series — 34 Michele Colagiovanni, C.PP.S. THE HIDDEN FATHER Francesco Albertini and the Missionaries of the Precious Blood TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction . 1 1 . Daily Life . 5 2 . From Intragna to Rome . 13 3 . The Mazzoneschis and the Albertinis . 19 4 . The Sources of His Spirituality . 25 5 . School and Society . 38 6 . An Interior Revolution . 47 7 . Family Reorganization . 60 8 . One Republic, Or Rather Two . 68 9 . Revolution In the Parish . 86 10 . A Fire Beneath the Ashes . 97 11 . The Association . 105 12. An Inflammatory Relic . 116 13 . The Revelatory Exile . 126 14 . Bastia, Corsica . 137 15 . Unshakeable . 152 16 . To Calvi: A Finished Man? . 161 17 . Deep Calls to Deep . 176 18 . Everyone Is in Rome . 183 19 . Reward and Punishment . 190 20 . The Great Maneuvers . 195 21 . Refounding . 207 22 . Women in the Field . 215 23 . An Experimental Diocese . 224 24 . A Pioneer Bishop . 233 25 . The Bishop and the Secretary . 243 26 . Death Comes Like a Thief . 252 27 . The Memory of the Just . 260 Epilogue . 262 Notes . 268 INTRODUCTION Most people familiar with Saint Gaspar know that Francesco Albertini was his spiritual director and was largely responsible for nurturing Gaspar’s devotion to the Precious Blood . Perhaps less well known is that it was Albertini, founder of the Archconfraternity of the Most Precious Blood, who wanted to see his association develop a clerical branch made up of priests who would renew the Church by spreading the devotion to the Blood of Christ . Albertini believed that Gaspar was exactly the right man to inaugurate this new venture, and he did all he could to encourage his beloved spiritual son to found the Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood 1. -

Sulla's Tabularium

Sulla’s Tabularium by Sean Irwin A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Architecture Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2010 © Sean Irwin 2010 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis examines the Tabularium in Rome. Very little is written about this building, despite its imposing size and commanding location at the juncture of the Forum Roma- num and the two crests of the Capitoline hill. It remains a cipher, unconsidered and unexplained. This thesis provides an explanation for the construction of the Tabularium consonant with the building’s composi- tion and siting, the character of the man who commissioned it, and the political climate at the time of its construction — reconciling the Tabularium’s location and design with each of these factors. Previous analyses of the Tabularium dwelt on its topo- graphic properties as a monumental backdrop for the Forum to the exclusion of all else. This thesis proposes the Tabularium was created by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla as a military installation forging an architectural nexus between political and religious authority in Rome. The Tabularium was the first instance of military architec- ture behind the mask of a civic program — a prototype for Julius and Augustus Caesar’s monumental interventions in the Forum valley. iii Acknowledgments First, I wish to convey my appreciation to my parents. -

The Goddess Mother of Money Dianne M. Juhl the Feminine Face Of

The Goddess Mother of Money Dianne M. Juhl the feminine face of money© June 2009 The Goddess Mother of Money Money talks and she has something to say. Wisdom is rooted in her very name. In everything she is abundant, richly bountiful, profusely fertile and generative. Money, in its origins, embodies the divine feminine who desires remembrance. This Thing We Call Money If we peel back thousands of years of cultural conditioning and assumptions to take a fresh look at money, we can begin with some very basic observations. Money is not a product of nature. Money doesn’t grow on trees. Pennies don’t rain from heaven. Money is an invention, a distinctly human invention. It is a total fabrication of our genius. We made it up and we manufacture it. It is an inanimate object that has appeared in many different forms in its more than 2,500-to-3,500-year history, whether we’re talking about shells or stones or ingots of precious metals, a paper bill or a blip on a computer screen. (Twist & Barker, 2003), p. 8) This thing we call “money” is plainly a human invention. The local living economies or the national and global economies in which money circulates are a social construction. Further, money takes innumerable forms as is typical of human inventions. For example, where I live in the Paciic Northwest region of the United States, the mediums of exchange (the measure and store of wealth too) has included: shells, ish teeth, whale bone, sea otter pelts, dried salmon, eagle feathers, cedar bark baskets, produce from strawberry ields or apple orchards, and millions of board feet of timber (ir, cedar, hemlock, sequoia). -

Arrival in Rome from Naples Via Train; Taxi from Station to Accommodations in Rome: Villa Riari, in the Trastevere (“Trans-Tiber”) Neighborhood

History 5010: Studies in Ancient History, May 2018 (8W1) Ancient & Medieval History in Rome Instructors: Dr. Christopher Fuhrmann ([email protected]) 264 Wooten Hall, x4527 The best way to contact me is via email. Put “Italy program” somewhere in the subject line. Dr. Silvio De Santis ([email protected]) 405A Language Building Course Description. This graduate class entails an intensive study program to Rome, and is linked to a section of HIST 4262 in southern Italy; together, the whole travel portion runs from May 13/14 – June 2, 2018, with some meetings before travel commences. It offers a rich overview to the history and culture of the city of Rome, from antiquity to the present, via personal encounters with the monuments, art, and topography of the city. The itinerary and academic plan are oriented towards ancient and medieval interests, but there is scope for students to explore interests in later eras, especially the Renaissance, the nineteenth-century Risorgimento (unification of Italy), the fascist period, and modern Italy (indeed, the physical nature of Rome as it exists now insists on considering different histories together). Relevant previous coursework is recommended but not required. Knowledge of Latin or Italian is not required. This class entails preparatory work during Spring 2018, and the completion of long papers (described below) during the first five-week Summer 2018 term. The travel portion does not extend beyond Maymester (3Wk1), and students can be back in Denton in time for Summer 5Wk1 classes. Course Goals. -

Hearken to the Sacred Geese of Juno Moneta

HEARKEN TO THE SACRED GEESE OF JUNO MONETA Antal E. Fekete E-mail: [email protected] On April 6 last I sent an open letter Congressmen Ron Paul of Texas accusing the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, Dr. Ben Bernanke, that (1) his program of Quantitative Easing(QE) whereby the Federal Reserve banks purchase U.S. Treasury paper directly from the U.S. Treasury is not authorized by the Federal Reserve Act and is therefore unlawful; (2) even if for the sake of argument we disregard where the Fed buys its paper, the sum appears to be higher than all available Federal Reserve credit outstanding and, moreover, the F.R. banks do not have unencumbered collateral to post in order to create more to conclude these purchases. I have received an unusually large feedback in my e-mail. People want to know how I can substantiate these accusations against Dr. Bernanke. Of course I cannot say that I have caught Dr. Bernanke red-handed. All I can do is to present circumstantial evidence. I start with a statement that I am fully aware of the seriousness of my accusations, and my responsibility in making them. I do not make them frivolously. I have been contemplating to do it for decades. My reasons for postponing have to do with calculating for maximum impact. I am but an isolated individual trying to take on the incumbent of one of the most powerful offices ever created on this earth. Wrong timing may be suicidal. I first came to suspect that in injecting F.R. -

The Roman Triumph As Material Expression of Conquest, 211-55 BCE

Engineering Power: The Roman Triumph as Material Expression of Conquest, 211-55 BCE Alyson Maureen Roy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Sandra Joshel, Chair Eric Orlin Joel Walker Adam Warren Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History © Copyright 2017 Alyson Maureen Roy University of Washington Abstract Engineering Power: The Roman Triumph as Material Expression of Conquest, 211-55 BCE Alyson Maureen Roy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sandra Joshel, History This dissertation explores the intersection between the Roman triumph, architecture, and material culture. The triumph was a military parade that generals were granted for significant victories and represented the pinnacle of an elite Roman man’s career, engendering significant prestige. My interest is in the transformation of the transitory parade, into what I term “material expressions of power” including architecture, decoration, inscriptions, and coins. I assert that from the mid-third century BCE through the mid-first century BCE, material expressions of power became of central importance to elite expressions of prestige. More importantly, by tracing the process of bringing plundered material to Rome, constructing victory monuments, and decorating them with plundered art, I have determined that this process had a profound impact on the development of a luxury art market in Rome, through which elite Romans bought objects that resembled triumphal plunder, and on the development of a visual language of power that the Romans used to talk to each other about conquest and that they then exported into the provinces as material expressions of their authority. -

Art and Politics in Republican Rome

ART AND POLITICS IN REPUBLICAN ROME ARH 362 20240 TTH 3.30–5.00 Prof. Penelope J. E. Davies DFA 2.518 232-2518 [email protected] Office hours: Tues 3–4 Course description: This course covers the art and architecture of Republican Rome, ca. 500-44 BC, when Rome began to establish dominance in the Mediterranean and to develop an artistic tradition that would flourish into the Empire. Copious wealth from victories abroad led to massive public works such as temples, civic buildings and triumphal monuments, which articulated the competing ambitions of elite families, jostling for political prominence. Students should gain a good grounding in Republican Roman visual culture and politics, and be able to assess works of art within their political and social context. Reading: Text: Penelope J. E. Davies, Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome (Cambridge 2017). For students with little familiarity with ancient Rome, A. and N. Ramage, Roman Art, from Romulus to Constantine, provides a superficial overview. General information concerning sites in Rome can be found in L. Richardson Jr’s A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome and the more comprehensive 5-volume Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae edited by M. Steinby (in a variety of languages). Both of these works are available in the Classics Library Reference Room. Also useful: Axel Boethius, Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture (Pelican 1970); Amanda Claridge, Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford 1998); Diana E.E. Kleiner, Roman Sculpture (Yale 1992); Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Cornell 1983); Timothy J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (Routledge 1995). Requirements and grading: Two mid-term exams (40% each); one presentation, researched and delivered in teams of 2–3 (20%).