2010 NJCL Ancient Geography Test

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Urban Development at Rome's Porta Esquilina and Church of San Vito

This is the first page only. On how to acquire the full article please click this link. Urban development at Rome’s Porta Esquilina and church of San Vito over the longue durée Margaret Andrews and Seth Bernard San Vito’s modern location on the Esquiline betrays little of the importance of the church’s site in the pre-modern city (fig. 1). The small church was begun under Pope Six- tus IV for the 1475 jubilee and finished two years later along what was at that time the main route between Santa Maria Maggiore and the Lateran.1 Modern interventions, however, and particularly the creation of the quartiere Esquilino in the late 19th c., changed the traffic patterns entirely. An attempt was made shortly thereafter to connect it with the new via Carlo Alberto by reversing the church’s orientation and constructing a new façade facing this modern street. This façade, built into the original 15th-c. apse, was closed when the church was returned to its original orientation in the 1970s, and, as a result, San Vito today appears shuttered.2 In the ancient and mediaeval periods, by contrast, San Vito was set at a key point in Rome’s eastern environs. It was at this very spot that the main route from the Forum, leading eastward up the Argiletum and clivus Suburanus, crossed the Republican city-walls at the Porta Esquilina to become the consular via Tiburtina (fig. 2). The central of the original three bays of the Augustan arch marking the Porta Esquilina still stands against the W wall of the early modern church, bearing a rededication in A.D. -

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: the IDEA of the MONUMENT in the ROMAN IMAGINATION of the AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller a Dissertatio

ROMAN ARCHITEXTURE: THE IDEA OF THE MONUMENT IN THE ROMAN IMAGINATION OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE by Nicholas James Geller A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo, Chair Associate Professor Ruth Rothaus Caston Professor Bruce W. Frier Associate Professor Achim Timmermann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people both within and outside of academia. I would first of all like to thank all those on my committee for reading drafts of my work and providing constructive feedback, especially Basil Dufallo and Ruth R. Caston, both of who read my chapters at early stages and pushed me to find what I wanted to say – and say it well. I also cannot thank enough all the graduate students in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan for their support and friendship over the years, without either of which I would have never made it this far. Marin Turk in Slavic Languages and Literature deserves my gratitude, as well, for reading over drafts of my chapters and providing insightful commentary from a non-classicist perspective. And I of course must thank the Department of Classical Studies and Rackham Graduate School for all the financial support that I have received over the years which gave me time and the peace of mind to develop my ideas and write the dissertation that follows. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……………………………………………………………………iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………....v CHAPTER I. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

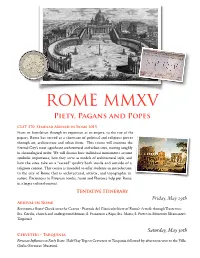

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Bsr Summer School 2-15(

1 BSR SUMMER SCHOOL 4-16 SEPTEMBER 2013 PROGRAMME Wednesday 4th September 16.15 Tea in courtyard; building & library tour 18.30 Introductory lecture (Robert Coates-Stephens) 19.30 Drinks 20.00 Dinner (as every day except Saturdays) Thursday 5th September THE TIBER Leave 8.30 Forum Boarium: Temples of Hercules & Portunus / 10.00 Area Sacra di S. Omobono [PERMIT] / ‘Arch of Janus’ / Arch of the Argentarii / S. Maria in Cosmedin & crypt (Ara Maxima of Hercules?) / Tiber Island / ‘Porticus Aemilia’ / 15.00 Monte Testaccio [PERMIT] 18.30 Seminar, in the BSR Library: “Approaches to Roman topography” (RCS) Friday 6th September FEEDING ROME: OSTIA Coach leaves 8.40 Ostia Antica, including 12.00 House of Diana [PERMIT] 18.30 Lecture: “The Triumph” (Ed Bispham) Saturday 7th September THE TRIUMPH OF THE REPUBLIC Leave 8.30 Pantheon / Area Sacra of Largo Argentina / Theatre of Pompey / Porticus of Octavia / Temples of Apollo Sosianus & Bellona / Theatre of Marcellus / 12.00 Three Temples of Forum Holitorium [PERMIT] / Circus Maximus / Meta Sudans / Arch of Constantine / Via Sacra: Arches of Titus, Augustus and Septimius Severus / 15.00 Mamertine prison [PERMIT] 18.30 Lecture: “The Fora” (Ed Bispham) Sunday 8th September FORUM ROMANUM & IMPERIAL FORA Leave 8.30 9.30 Forum Romanum: Introduction, central area [PERMIT] / Comitium, Atrium Vestae, Temples of Concord, Vespasian, Saturn, Castor, Divus Julius, Antoninus and Faustina, Basilicas Aemilia and Julia / Capitoline Museums & Tabularium / 14.00 Imperial Fora: Museo dei Fori Imperiali & Markets of -

VERGIL in VROMA: Exploring the Capitoline Hill

VERGIL IN VROMA: Exploring the Capitoline Hill Goals: 1. Practice methods of navigation and conversation in the MOO 2. Explore some of the educational resources in VRoma 3. Use virtual space to come to a better understanding of Roman culture and civilization through group discussion of issues surrounding a selected site. 4. Enhance understanding and appreciation of the Aeneid through exploring the epic’s connections with the city of Rome. Worksheets: 1. Quick Start Guide to the VRoma Learning Environment 2. Group Site Assignment General Instructions: Explore your assigned site completely, visiting all its rooms and examining its varied contents, including texts, objects, bots, and links Read your Site Assignment through carefully to be clear about the topics you are asked to discuss. When you have completed the assignment, save your HTML Chat Log and email a copy of it to your professor. Site Assignment: Teleport to the site by typing @go Capitoline 1. Read the materials there to get a sense of the geography and topography of the area. Why did this hill come to have such symbolic power for the Romans? Compare and contrast the use that Ovid and Horace make of this symbolism. What does Vergil use instead of the hill itself to symbolize Rome's ability to endure and prevail? 2. Then using the exit links at the bottom of the screen, move to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and read about its structure, divinities, and history. What was unusual about this temple in comparison with the newer temples being built by Augustus, and why didn't the Romans want to change its structure? What links does the Jupiter in this temple have with the god portrayed by Vergil? What about the Juno in this temple? As protectress of Rome, she is certainly different from Vergil's goddess. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 12 February 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Witcher, R.E. (2013) '(Sub)urban surroundings.', in The Cambridge companion to Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 205-225. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/classical-studies/ancient-history/cambridge-companion- ancient-rome Publisher's copyright statement: c Cambridge University Press 2015 Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk R. D ON t\1 J l l£R such monumen ts. not to mention their external appearance. The testi mony of anci ent writers attests the importance of thi s visual medium, which played a central role in enabling the Roman elite to communicate their social value s and to win everlasting fame. Yet in the end it seems 12 : (SUB)URBAN that not everyone pursued glor y through a commemorative monument. -

The City Boundary in Late Antique Rome Volume 1 of 1 Submitted By

1 The City Boundary in Late Antique Rome Volume 1 of 1 Submitted by Maria Anne Kneafsey to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in December 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changing meaning and conceptualisation of the city boundary of Rome, from the late republic and imperial periods into late antiquity. It is my aim in this study to present a range of archaeological and historical material from three areas of interest: the historical development of the city boundary, from the pomerium to the Aurelian wall, change and continuity in the ritual activities associated with the border, and the reasons for the shift in burial topography in the fifth century AD. I propose that each of these three subject areas will demonstrate the wide range of restrictions and associations made with the city boundary of Rome, and will note in particular instances of continuity into late antiquity. It is demonstrated that there is a great degree of continuity in the behaviours of the inhabitants of Rome with regard to the conceptualisation of their city boundary. The wider proposal made during the course of this study, is that the fifth century was significant in the development of Rome – archaeologically, historically, and conceptually – but not for the reasons that are traditionally given. -

Volcanic Eruptions Damned the River with Deposits of Ash, Called Tuffs6

volcanic eruptions damned the river with deposits of ash, called tuffs6, and changed its course. Both of the volcanic fields, the Sabatini to the northwest and the Alban hills to the southeast, played important roles in creating the terrain; plateaus pinching the Tiber floodplain and creating high ground for Rome (Heiken, Funiciello & De Rita, 2005:11). Despite the advantageous location, Rome is still susceptible to flooding due to the large drainage area of the Tiber. The climate from the end of the republic, throughout the years of the Empire, up to perhaps between 800 and 1200 A.D., was warmer and drier than later years. During the wet period between 1310 and 1320 A.D., and the so-called "little ice age" of 1500 to 1800 A.D., Rome was more susceptible to flooding (Lamb, 1995). This is perhaps a good thing, as repeated natural destruction of the city may have had a large influence on the superstitious Roman mind, providing "evidence" for the displeasure of the gods, and perhaps the resulting abandonment of the site. The Alban hills are approximately 50 kilometres in diameter with an elevation of nearly 1000 metres above sea level, and span the coastal plain between the Apennines and the sea. The summit is broad and dominated by a caldera, which has mostly been covered with material from later volcanoes. The slopes were once covered with oak, hazel and maple trees. Archaeolog- ical evidence from around the edges of the Nemi and Albano lakes indicate that the area has been occupied since the Bronze Age. -

The Hidden Father, Francesco Albertini.Pdf

C.PP.S. Resource Series — 34 Michele Colagiovanni, C.PP.S. THE HIDDEN FATHER Francesco Albertini and the Missionaries of the Precious Blood TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction . 1 1 . Daily Life . 5 2 . From Intragna to Rome . 13 3 . The Mazzoneschis and the Albertinis . 19 4 . The Sources of His Spirituality . 25 5 . School and Society . 38 6 . An Interior Revolution . 47 7 . Family Reorganization . 60 8 . One Republic, Or Rather Two . 68 9 . Revolution In the Parish . 86 10 . A Fire Beneath the Ashes . 97 11 . The Association . 105 12. An Inflammatory Relic . 116 13 . The Revelatory Exile . 126 14 . Bastia, Corsica . 137 15 . Unshakeable . 152 16 . To Calvi: A Finished Man? . 161 17 . Deep Calls to Deep . 176 18 . Everyone Is in Rome . 183 19 . Reward and Punishment . 190 20 . The Great Maneuvers . 195 21 . Refounding . 207 22 . Women in the Field . 215 23 . An Experimental Diocese . 224 24 . A Pioneer Bishop . 233 25 . The Bishop and the Secretary . 243 26 . Death Comes Like a Thief . 252 27 . The Memory of the Just . 260 Epilogue . 262 Notes . 268 INTRODUCTION Most people familiar with Saint Gaspar know that Francesco Albertini was his spiritual director and was largely responsible for nurturing Gaspar’s devotion to the Precious Blood . Perhaps less well known is that it was Albertini, founder of the Archconfraternity of the Most Precious Blood, who wanted to see his association develop a clerical branch made up of priests who would renew the Church by spreading the devotion to the Blood of Christ . Albertini believed that Gaspar was exactly the right man to inaugurate this new venture, and he did all he could to encourage his beloved spiritual son to found the Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood 1.