Biography of Edward Irving BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995) VOLUME 11 Section G: Societies and organisations by Timothy E. Powell and Caroline Thibeaud NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn 124 NCUACS 104/3/02 SECTION G SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS G.1-G.732 G.1 ACADEMIA EUROPAEA G.2-G.6 AMERICAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION G.7-G.11 BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE G.12-G.63 COSPAR (COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH) G.64-G.67 DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY: ENERGY TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT UNIT G.68-G.76 EUROPEAN GEOPHYSICAL SOCIETY G.77 EUROPEAN PLANETARY GEOLOGY CONSORTIUM G.78-G.111 EUROPEAN SCIENCE FOUNDATION G.112-G.1S3 EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY G.1S4-G.230 INTERNATIONAL ASTRONOMICAL UNION G.231-G.277 INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEODESY AND GEOPHYSICS G.278 INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES G.279-G.294 INTER-UNION COMMISSION FOR STUDIES OF THE MOON G .29S-G .300 JOINT SERVICES WEST-EAST SAHARA EXPEDITION G.301, G.302 LIBERAL PARTY G.303-G.311 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE S.K. Runcorn 125 NCUACS 104/3/02 Societies and organisations G.312 METEORITICAL SOCIETY G.313 MINERALOLOGICAL SOCIETY G.314-G.319 MINISTRY OF SUPPLY G.320 MUSEUM OF NORTHERN ARIZONA G.321-G.333 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION (NASA) G.334-G.338 NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION G.339-G.342 NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANISATION (NATO) G.343 NUFFIELD FOUNDATION G.344-G.365 POI\ITIFICAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES G.366 PROVINCIAAL UTRECHTS GENOOTSCHAP VAN KUISTEN EN WETENSCHAPPEN G.367-G.386 ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY G.387-G.731 ROYAL SOCIETY G.732 STANDING CONFERENCE OF PROFESSORS OF PHYSICS S.K. -

SCIENCE and SUSTAINABILITY Impacts of Scientific Knowledge and Technology on Human Society and Its Environment

EM AD IA C S A C I A E PONTIFICIAE ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARVM ACTA 24 I N C T I I F A I R T V N Edited by Werner Arber M O P Joachim von Braun Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo SCIENCE and SUSTAINABILITY Impacts of Scientific Knowledge and Technology on Human Society and Its Environment Plenary Session | 25-29 November 2016 Casina Pio IV | Vatican City LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA VATICAN CITY 2020 Science and Sustainability. Impacts of Scientific Knowledge and Technology on Human Society and its Environment Pontificiae Academiae Scientiarvm Acta 24 The Proceedings of the Plenary Session on Science and Sustainability. Impacts of Scientific Knowledge and Technology on Human Society and its Environment 25-29 November 2016 Edited by Werner Arber Joachim von Braun Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo EX AEDIBVS ACADEMICIS IN CIVITATE VATICANA • MMXX The Pontifical Academy of Sciences Casina Pio IV, 00120 Vatican City Tel: +39 0669883195 • Fax: +39 0669885218 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.pas.va The opinions expressed with absolute freedom during the presentation of the papers of this meeting, although published by the Academy, represent only the points of view of the participants and not those of the Academy. ISBN 978-88-7761-113-0 © Copyright 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, pho- tocopying or otherwise without the expressed written permission of the publisher. PONTIFICIA ACADEMIA SCIENTIARVM LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA VATICAN CITY The climate is a common good, belonging to all and meant for all. -

California Institute of Technology Catalog 1957-8

Bulletin of the California Institute of Technology Catalog 1957-8 PAS ADEN A, CALIFORNIA BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 66 NUMBER 3 The California Institute of Technology Bulletin is published quarterly Entered as Second Class Matter at the Post Office at Pasadena, California, under the Act of August 24, 1912 CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY A College, Graduate School, and Institute of Research in Science, Engineering, and the Humanities CATALOG 1957 -1958 PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE SEPTEMBER, 1957 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS PART ONE. GENERAL INFORMATION PAGE Academic Calendar .............................. __ ...... _.. _._._. __ . __ . __ . __ .. _____ 11 Board of Trustees ..................... _...................... _... __ ....... _.. ______ .. 15 Trustee Committees ......................... _..... __ ._ .. _____ .. _........... _... __ .. 16 Administrative Officers of the Institute ..... ___ ........... _.. _.. _.... 18 Faculty Officers and Committees, 1957-58 ... __ .. __ ._ .. _... _......... _.... 19 Staff of Instruction and Research-Summary ._._ .. ___ ... ___ ._. 21 Staff of Instruction and Research .... _. __ .. __ .... _____ ._ .. __ .... _ 38 Fellows, Scholars and Assistants _.. _: __ ... _..._ ...... __ . __ .. _ 66 California Institute Associates .... _... _ ... _._ .. _... __ ... ._ .. __ .. _.. 79 Historical Sketch .................... _..... __ ........... __ .. __ ... _.... _... _.. ____ . 83 Educational Policies ...... _.. __ .... __ . 88 Industrial Associates ........_. __ 91 Industrial -

History of Oceanography, Number 14

No. 14 September 2002 CONTENTS EDITORIAL........................................................................................................................ 1 IN MEMORIAM PHILIP F. REHBOCK............................................................................ ARTICLE.......................................................................................................................... Scientific research, management advice; evolution of ICES’s dual identity ICHO VII IN KALINGRAD 2003....................................................................................... CLASSES IN HISTORY OF MARINE SCIENCES........................................................... BOOK ANNOUNCEMENTS AND REVIEWS................................................................. KEITH RUNCORN PAPERS.............................................................................................. NEWS AND EVENTS........................................................................................................ ANNUAL BIBLIOGRAPHY AND BIOGRAPHIES.......................................................... INTERNATIONAL UNION OF THE HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE DIVISION OF THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE COMMISSION OF OCEANOGRAPHY President Eric L. Mills Department of Oceanography Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 4J1 CANADA Vice Presidents Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre La Verveine 7, Square Kraemer 06240 Beausoleil, FRANCE Margaret B. Deacon 3 Rewe Court, Heazille Barton Rewe, Exeter EX5 4HQ Devon, UNITED KINGDOM Walter Lenz Institut für Klima-und -

Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS ( 1922-1995)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS ( 1922-1995) VOLUME I General Introduction Section A: Biographical Section B: University of Manchester Section C: University of Newcastle Section D: Research Section E: Publications Section F: Lectures by Timothy E. Powell and Caroline Thibeaud NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn NCUACS 104/3/02 Title: Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995), geophysicist Compiled by: Timothy E. Powel! and Peter Harper Description level: Fonds Date of material: 1936-1995 Extent of material: 100 boxes, ca 2,800 items Deposited in: College Archives, Imperial College London Reference code: GB 0098 B/RUNCORN © 2002 National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, University of Bath. NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn 2 NCUACS 104/3/02 The work of the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists, and the production of this catalogue, are made possible by the support of the following societies and organisations: Friends of the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics The British Computer Society The British Crystallographic Association The Geological Society The Institute of Physics The Royal Society The Royal Astronomical Society The Royal Society of Chemistry The Wellcome Trust S.K. Runcorn 3 NCUACS 104/3/02 NOT ALL THE MATERIAL IN THIS COLLECTION MAY YET BE AVAILABLE FOR CONSULTATION. ENQUIRIES SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FIRST INSTANCE TO: THE COLLEGE ARCHIVIST -

Adirondack Chronology

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks Chronology Management Team Gary Chilson Professor of Environmental Studies Editor, The Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies Paul Smith’s College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 265 Paul Smiths, NY 12970-0265 [email protected] Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 20 January (No. 43) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. It is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks. It is hoped that it may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in-depth research. Can the ARL further serve your research needs? To find out, visit our web page, or even better, visit the ARL at the Center for the Forest Preserve, 897 St. David's Lane, Niskayuna, N.Y., 12309. The ARL houses one of the finest collections available of books and periodicals, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and private papers dealing with the Adirondacks. Its volunteers will gladly assist you in finding answers to your questions and locating materials and contacts for your research projects. Introduction Is a chronology of the Adirondacks really possible? -

CURRICULUM VITAE -- ROBERT MILLER HAZEN – June 2015 Work

CURRICULUM VITAE -- ROBERT MILLER HAZEN – June 2015 Work Address (CIW): Geophysical Laboratory 5251 Broad Branch Road, NW Washington, DC 20015-1305 Work Telephone: 202-478-8962 FAX 202-478-8901 E-mail [email protected] Websites: http://hazen.gl.ciw.edu/ and http://deepcarbon.net Work Address (GMU): George Mason University Mail Stop 1D6 Fairfax, VA 22030-4444 Work Telephone: 703-993-2163 FAX 703-993-2175 Place of Birth: Rockville Centre, NY Citizenship: USA Date of Birth: November 1, 1948 Marital Status: Married August 9, 1969 to Margaret Joan Hindle Children: Benjamin Hindle Hazen (b. June 18, 1976) Elizabeth Brooke Hazen (b. September 1, 1978) Education: Massachusetts Inst. of Tech. 1966-1970 B.S. Earth Science Massachusetts Inst. of Tech. 1970-1971 S.M. Earth Science Indiana University 1969 Summer Field Geology Harvard University 1971-1975 Ph.D. Mineralogy & Crystallography Employment History (Scientific Research and Education): Executive Director and PI, Deep Carbon Observatory, 2008- Clarence Robinson Professor of Earth Science, George Mason University, 1989- Senior Staff Scientist, Geophysical Laboratory, Carnegie Institution, 1978- President, Robert & Margaret Hazen Foundation, 2008- Research Associate, Smithsonian Institution, Department of Paleobiology, 2007- President, Hazen Associates, Ltd., 1994-2007 Professional Trumpeter, 1965-2013 Visiting Researcher, Univ. California at Santa Barbara, Chemistry Department, 1987. Summer Faculty, IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, 1978. Research Associate, Geophysical Laboratory, 1976-1978. NATO Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Cambridge, Department of Mineralogy and Petrology, Cambridge, England, 1975-1976. Research Assistant and Teaching Fellow, Harvard, 1973-1975. Field Assistant, U. S. Geological Survey, Summers of 1970 and 1971. Curator of Geological Collections, M.I.T., 1967-1970. -

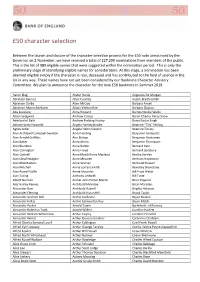

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

Pdf Preprint

TREATISE ON GEOPHYSICS VOLUME 7 Mantle Dynamics 7.01 Mantle Dynamics Past, Present and Future: An Introduction and Overview∗ David Bercovici, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA ◦ 2007 Author preprint Contents 7.01.1 Introduction 2 7.01.2 A Historical Perspective on Mantle Dynamics 2 7.01.2.1 Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (1753-1814) . ........................ 3 7.01.2.2 John William Strutt, Lord Rayleigh (1842-1919) . .......................... 7 7.01.2.3 Henri Claude B´enard (1874-1939) . ..................... 10 7.01.2.4 Arthur Holmes (1890-1965) . ................... 13 7.01.2.5 Anton Hales and Chaim Pekeris . ................... 15 7.01.2.5.1 Anton Linder Hales (1911-2006) . .................. 16 7.01.2.5.2 Chaim Leib Pekeris (1908-1993) . .................. 18 7.01.2.6 Harry Hammond Hess (1906-1969) . ................... 21 7.01.2.7 Stanley Keith Runcorn 1922-1995 . ..................... 23 7.01.2.8 Mantle convection theory in the last 40 years . ......................... 26 7.01.3 Observations and evidence for mantle convection 26 7.01.4 Mantle properties 27 7.01.5 Questions about mantle convection we have probably answered 28 7.01.5.1 Does the mantle convect? . .................. 28 7.01.5.2 Is the mantle layered at 660 km? . ................... 29 7.01.5.3 What are the driving forces of tectonic plates? . .......................... 29 7.01.6 Major unsolved issues in mantle dynamics 31 ∗D. Bercovici, Mantle dynamics past, present and future: An introduction and overview, in Treatise on Geophysics, vol.7 “Mantle Dynamics”, D. Bercovici ed.; G.Schubert, ed. in chief, Elsevier:New York, Ch.1, pp.1-30, 2007 1 2 An Introduction and Overview 7.01.6.1 Energy sources for mantle convection . -

Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995)

Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Stanley Keith Runcorn FRS (1922-1995) VOLUME III Section H: Visits and conferences Section J: Correspondence Index of correspondents by Timothy E. Powell and Caroline Thibeaud NCUACS catalogue no. 104/3/02 S.K. Runcorn 215 NCUACS 104/3/02 SECTION H VISITS AND CONFERENCES H.1-H.897 From the 1950s to his death, Runcorn made a very great number of visits abroad, mainly to the USA but also to the continent of Europe and a few to Australia, Asia etc. It is sometimes difficult to keep an exact track of his whereabouts given his peripatetic lifestyle and it is not always clear whether planned visits did indeed always take place. Although his visits to the United States generally were in connection with specific conferences or meetings - he was a regular attender at Lunar and Planetary Science conferences in Houston, Texas and American Geophysical Union meetings, for example - he very often also took the opportunity to visit colleagues and deliver lectures at other research centres and there may be voluminous correspondence relating to such more informal visits. There is also material relating to meetings within the UK. There is good documentation of Runcorn's attendance at Royal Astronomical Socjety and Royal Society discussion meetings, and of his work promoting, organising and contributing to NATO Advanced Study Institutes held at Newcastle. Not all of Runcorn's visits are recorded, even in this very large section. Many meetings in connection with the international and European geophysics and planetary science organisations with which he was associated are documented in section G, Societies and organisations. -

Guide to the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Papers 1913-2011

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Papers 1913-2011 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 4 Scope Note 5 Related Resources 9 Subject Headings 9 INVENTORY 10 Series I: Personal Correspondence and Papers 10 Subseries 1: Biographical materials and personal papers 10 Subseries 2: Personal correspondence 12 Series II: Scientific Correspondence 20 Series III: Scientific Writings 45 Series IV: Lecture Notes 122 Subseries 1: Cambridge University notes 122 Subseries 2: University of Chicago Notes 124 Subseries 3: Special lectures 130 Series V: Astrophysical Journal Records 134 Series VI: Articles by Colleagues 136 Subseries 1: Offprints 136 Subseries 2: Typescripts 136 Series VII: Addenda 137 Subseries 1: Personal and Biographical 140 Sub-subseries 1: General personal and biographical papers 140 Sub-subseries 2: Personal correspondence 154 Sub-subseries 3: Publications 158 Sub-subseries 4: Chandra X-Ray Observatory 163 Subseries 2: Correspondence 164 Subseries 3: Writing 193 Subseries 4: Writings about Chandrasekhar 223 Subseries 5: Writings by others 229 Subseries 6: Audiovisual 239 Sub-subseries 1: Photographic material 239 Sub-subseries 2: Audio 267 Sub-subseries 3: Video 275 Subseries 7: Oversize 276 Subseries 8: Artifacts and framed items 292 Subseries 9: Medals 295 Subseries 10: Restricted 297 Sub-subseries 1: Administrative records and referee’s reports 297 Sub-subseries 2: Financial records 297 Sub-subseries 3: Letters of recommendation for colleagues and faculty appointment301 material Sub-subseries 4: Student grades and letters of recommendation 305 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.CHANDRASEKHAR Title Chandrasekhar, Subrahmanyan. -

Dawies Az Ötödik Csoda.Pdf

PAUL DAVIES Az ötödik csoda AZ ÉLET EREDETÉNEK NYOMÁBAN VINCE KIADÓ A mű eredeti címe: The Fifth Miracle. The Search for the Origin of Life Copyright © Orion Productions, 1998 All rights reserved A fordítás az Allen Lane, The Penguin Press 1998. évi kiadása alapján készült Fordította: Kertész Balázs A fordítást ellenőrizte, a magyar kiadás jegyzeteit és a magyar nyelvű ajánlott irodalom jegyzékét összeállította: dr. Almár Iván Minden jog fenntartva. Kritikákban és recenziókban felhasznált rövid idézetek kivételével a mű egyetlen része sem publikálható semmilyen eljárással a jogtulajdonos előzetes engedélye nélkül Hungarian translation © Kertész Balázs, 2000 Kiadta a Vince Kiadó Kft. 2000 (1027 Budapest, Margit körút 64/b) A kiadásért a Vince Kiadó igazgatója felel Felelős szerkesztő: Teravagimov Péter Műszaki szerkesztő: M. Beck Anna ISBN 963 9192 78 3 Keith Runcorn emlékére Nyomás és kötés: Szekszárdi Nyomda Kft. Felelős vezető: Vadász József igazgató A könyv digitális változatát a NeTtErRoRiStA eLiTkOmMaNdÓ készítette! Az élet eredete egyike a tudomány legérdekesebb és még megválaszolatlan kérdéseinek. Az élet csupán egy kémiai baleset eredménye, ami egyedülálló az Univerzumban? Vagy éppen ellenkezőleg, mélyen bele van vésve a természet törvényeibe, és fel is bukkan ott, ahol a körülmények kedvezőek? Paul Davies, a világszerte elismert tudós és több népszerű könyv szerzője ebben a művében a legújabb biogenezis- elméleteket veszi sorra. A csak nemrég felfedezett, a Föld forró mélységeiben tanyázó „élő kövületek” és baktériumok lehetséges nyomai egy Marsról származó meteoritban alaposan felforgatták az eddigi nézeteket a legkorábbi élő szervezetekről. Az egyre gyarapodó bizonyítékok amellett szólnak, hogy az élet valahol mélyen a felszín alatt, korábban elviselhetetlennek tartott körülmények közepette született, és sziklákba zártan akár utazhatott is a Föld és Mars között, vagy talán bárhová a világűrön át.