The Cassone Paintings of Francesco Di Giorgio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Painting in Renaissance Siena

Figure r6 . Vecchietta. The Resurrection. Figure I7. Donatello. The Blood of the Redeemer. Spedale Maestri, Torrita The Frick Collection, New York the Redeemer (fig. I?), in the Spedale Maestri in Torrita, southeast of Siena, was, in fact, the common source for Vecchietta and Francesco di Giorgio. The work is generally dated to the 1430s and has been associated, conjecturally, with Donatello's tabernacle for Saint Peter's in Rome. 16 However, it was first mentioned in the nirieteenth century, when it adorned the fa<;ade of the church of the Madonna della Neve in Torrita, and it is difficult not to believe that the relief was deposited in that provincial outpost of Sienese territory following modifications in the cathedral of Siena in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. A date for the relief in the late I4 5os is not impossible. There is, in any event, a curious similarity between Donatello's inclusion of two youthful angels standing on the edge of the lunette to frame the composition and Vecchietta's introduction of two adoring angels on rocky mounds in his Resurrection. It may be said with little exaggeration that in Siena Donatello provided the seeds and Pius II the eli mate for the dominating style in the last four decades of the century. The altarpieces commissioned for Pienza Cathedral(see fig. IS, I8) are the first to utilize standard, Renaissance frames-obviously in con formity with the wishes of Pius and his Florentine architect-although only two of the "illustrious Si enese artists," 17 Vecchietta and Matteo di Giovanni, succeeded in rising to the occasion, while Sano di Pietro and Giovanni di Paolo attempted, unsuccessfully, to adapt their flat, Gothic figures to an uncon genial format. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

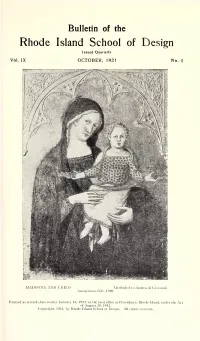

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

![Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7048/madonna-and-child-with-the-blessing-christ-and-saints-peter-james-major-anthony-abbott-and-a-deacon-saint-entire-triptych-c-1997048.webp)

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Martino di Bartolomeo Sienese, active 1393/1434 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [entire triptych] c. 1415/1420 tempera on panel Inscription: middle panel, on Christ's book: Ego S / um lu / x m / undi / [et] via / veritas / et vita / quise / gui ... (I am the light of the world and the way, the truth and the life; a conflation of John 8:12 and 14:6) [1] Gift of Samuel L. Fuller 1950.11.1.a-c ENTRY This triptych's image of the Madonna and Child recalls the type of the Glykophilousa Virgin, the “affectionate Madonna.” She rests her cheek against that of the child, who embraces her. The motif of the child’s hand grasping the hem of the neckline of the Virgin’s dress seems, on the other hand, to allude to the theme of suckling. [1] The saints portrayed are easily identifiable by their attributes: Peter by the keys, as well as by his particular facial type; James Major, by his pilgrim’s staff; Anthony Abbot, by his hospitaller habit and T-shaped staff. [2] But the identity of the deacon martyr saint remains uncertain; he is usually identified as Saint Stephen, though without good reason, as he lacks that saint’s usual attributes. Perhaps the artist did not characterize him with a specific attribute because the triptych was destined for a church dedicated to him. -

La Pinacoteca Nazionale Di Siena. Quattrocento E Primi Del Cinquecento

A70 15 La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena A71 ItInerArIo 15 a Pinacoteca di Siena ha sede nei palazzi le confraternite laiche soppresse dal grandu- LBonsignori e Brìgidi. Il primo è un edi- ca Pietro Leopoldo nel 1783. ficio costruito dopo il 1440 in forme gotiche Dopo il 1810, anno in cui Napoleone per volontà del banchiere senese Giovanni decretò la soppressione di alcuni ordini La Pinacoteca di Guccio Bichi; il secondo, invece, risale al religiosi, furono acquisiti dalla Pinacoteca Trecento. anche molti capolavori provenienti da chie- Nazionale Il nucleo primitivo delle collezioni della se e monasteri. Donazioni, depositi e altre di Siena. Pinacoteca è costituito dalla raccolta messa soppressioni (1867) hanno accresciuto nel assieme nella seconda metà del Settecen- corso degli ultimi anni il patrimonio d’arte Quattrocento to dall’abate Giuseppe Ciaccheri (Livorno, del museo, in specie di dipinti senesi dalle 1723-Siena, 1804), acquistando le opere del- origini (XIII secolo) al Manierismo. e primi del Cinquecento Piante del primo, secondo e terzo piano. 26 11 10 6 23 14 7 30 24 9 5 8 29 27 22 13 12 31 15 20 1 37 19 32 15 bis 4 3 Via San Pietro, 29 33 34 35 36 16 17 2 Siena 1-2. origini 12-14. Pittura senese della pittura del primo senese e Guido Quattrocento da Siena 15-19. Pittura senese 3-4. Duccio e pittori della seconda ducceschi metà del 5-6. Simone Martini Quattrocento 3° Piano Collezione Spannocchi e seguaci 26. Le sculture 7-8. Ambrogio e 20-23. Pittori del Pietro Lorenzetti Quattrocento 10. -

Vecchietta's Reliquary Cupboard: Frame And

VECCHIETTA’S RELIQUARY CUPBOARD: FRAME AND FRAMED AT SANTA MARIA DELLA SCALA, SIENA Jordan Famularo The national museum in Siena houses the remains of a painted reliquary cupboard made in the fifteenth century by Lorenzo di Pietro, known as Vecchietta (fig. 1). Two doors and part of their attached framework are all that survive from the original container. Vecchietta began work on the cupboard in 1445 and probably completed it late that year or in 1446.1 The cupboard doors and frame were installed over a cavity in the south wall of a newly constructed sacristy in Santa Maria della Scala,2 the church and hospital complex located on the south side of Siena’s Piazza del Duomo. The sacristy soon underwent more construction, during which the cupboard doors and frame were removed. The art- historical literature provides no indication that Vecchietta’s cupboard was reinstalled elsewhere in the church in the wake of renovations made to it in the second half of the fifteenth century. During the cupboard’s removal, its sides were damaged, but otherwise the surviving parts are in a good state of preservation.3 The cupboard was commissioned in the midst of a campaign led by Giovanni Buzzichelli, the rector of Santa Maria della Scala, to strengthen the hospital’s finances by attracting increased flows of pilgrims and pious donations. From its earliest documented history, Santa Maria della Scala served travelers and pilgrims. Siena was on the main route between Rome and places northward, whether northern Italy or transalpine locales.4 Two pilgrimage halls were added to the building in 1325 and enlarged periodically; by 1399 there were beds enough to accommodate 130 adults. -

Italy, 1200 to 1400

Italy, 1200 to 1400 1 Italy Around 1400 2 Goals • Understand the influence of the Byzantine and classical worlds on the art and architecture. • Understand the rejection of medieval artistic elements and the growing interest in the natural world. • Examine the revival of classical values, in particular, the growth of humanism. • Examine elements of the patronage system that developed at that time, and the patronage rivalries among the developing city states. • Examine the architecture and art as responsive to the growing European power structures at that time. 3 Figure 19-6 Nave of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy, ca. 1246-1470. 4 Let’s Go To Pisa! 5 Figure 17-25 Cathedral complex, Pisa, Italy; cathedral begun 1063; baptistery begun 1153; campanile begun 1174. 6 Rejection of Medieval Artistic Values • Understand the influence of the Byzantine and classical worlds on the art and architecture. • Understand the rejection of medieval artistic elements and the growing interest in the natural world. • Examine the artistic interest in illusionism, pictorial solidity, spatial depth, and emotional display in the human figure. 7 Figure 19-2 NICOLA PISANO, pulpit of the baptistery, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. Marble, 15’ high. 8 Figure 19-3 NICOLA PISANO, Annunciation, Nativity, and Adoration of the Shepherds, relief panel on the baptistery pulpit, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. Marble, 2’ 10” x 3’ 9”. 9 Battle of Romans and barbarians (Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus), from Rome, Italy, ca. 250– 260 CE. Marble, 5’ high. Museo Nazionale Romano-Palazzo Altemps, Rome. 11 Figure 19-3 NICOLA PISANO, Annunciation, Nativity, and Adoration of the Shepherds, relief panel on the baptistery pulpit, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. -

Bulgarini, Saint Francis, and the Beginnings of a Tradition

BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Laura Dobrynin June 2006 This thesis entitled BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION by LAURA DOBRYNIN has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Associate Professor of Art History Charles McWeeney Dean, College of Fine Arts DOBRYNIN, LAURA, M.A., June 2006, Art History BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION (110 pp.) Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw This thesis examines the influence of the fourteenth-century Sienese painter Bartolommeo Bulgarini through his depiction of Saint Francis of Assisi exposing his side wound. By tracing the development of this motif from its inception to its dispersal in selected Tuscan panel paintings of the late-1300’s, this paper seeks to prove that Bartolommeo Bulgarini was significant to its formation. In addition this paper will examine the use of punch mark decorations in the works of artists associated with Bulgarini in order to demonstrate that the painter was influential in the dissemination of the motif and the subsequent tradition of its depiction. This research is instrumental in recovering the importance of Bartolommeo Bulgarini in Sienese art history, as well as in establishing further proof of the existence of the hypothesized Sienese “Post-1350” Compagnia, a group of Sienese artists who are thought to have banded together after the bubonic plague of c.1348-50. -

The Assumption of the Virgin with Busts of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin of the Annunciation C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Paolo di Giovanni Fei Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411 The Assumption of the Virgin with Busts of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin of the Annunciation c. 1400/1405 tempera on panel painted surface: 66.5 × 38.1 cm (26 3/16 × 15 in.) overall: 79.8 × 51 cm (31 7/16 × 20 1/16 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.71 ENTRY Although the bodily Assumption of the Virgin did not officially become the dogma of the Catholic Church until 1950, [1] it began to be represented in art in the eleventh century (with some isolated examples even earlier than that). [2] In Italy, one of the first large-scale images of the Assumption is found in Siena, in the great rose window of the cathedral, based on a cartoon by Duccio di Buoninsegna (Sienese, c. 1250/1255 - 1318/1319) and dating to c. 1288. Here Mary is sitting in a mandorla of light, supported by angels in flight, with her hands joined in prayer, in the pose in which she would be frequently portrayed in the following centuries. [3] The image of Mary borne up to heaven by angels would then be enriched with further details in the course of the fourteenth century. In particular, it would be accompanied (as in the present panel) with a scene of the apostles with expressions of wonder and awe gathered around the Virgin’s tomb, which is filled with flowers only, [4] and with the figure of Saint Thomas, who is shown kneeling The Assumption of the Virgin with Busts of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin of 1 the Annunciation National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries on the Mount of Olives, separated from his companions and praying to Mary.