The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Paolo di Giovanni Fei Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411 The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple 1398-1399 tempera on wood transferred to hardboard painted surface: 146.1 × 140.3 cm (57 1/2 × 55 1/4 in.) overall: 147.2 × 140.3 cm (57 15/16 × 55 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.4 ENTRY The legend of the childhood of Mary, mother of Jesus, had been formed at a very early date, as shown by the apocryphal Gospel of James, or Protoevangelium of James (second–third century), which for the first time recounted events in the life of Mary before the Annunciation. The iconography of the presentation of the Virgin that spread in Byzantine art was based on this source. In the West, the episodes of the birth and childhood of the Virgin were known instead through another, later apocryphal source of the eighth–ninth century, attributed to the Evangelist Matthew. [1] According to this account of her childhood, Mary, on reaching the age of three, was taken by her parents, together with offerings, to the Temple of Jerusalem, so that she could be educated there. The child ascended the flight of fifteen steps of the temple to enter the sacred building, where she would continue to live, fed by an angel, until she reached the age of fourteen. [2] The legend linked the child’s ascent to the temple and the flight of fifteen steps in front of it with the number of Gradual Psalms. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85162-6 - Artistic Centers of the Italian Renaissance: Florence Edited by Francis Ames-Lewis Table of Contents More information CONTENTS S List of Illustrations page xi List of Contributors xxi Acknowledgments xxiii introduction 1 Francis Ames-Lewis 1 florence, 1300–1600 7 Francis W. Kent 2 florence before the black death 35 Janet Robson 3 the arts in florence after the black death 79 Louise Bourdua 4 republican florence, 1400–1434 119 Adrian W. B. Randolph 5 the florence of cosimo “il vecchio” de’ medici: within and beyond the walls 167 Roger J. Crum 6 art and cultural identity in lorenzo de’ medici’s florence 208 Caroline Elam 7 republican florence and the arts, 1494–1513 252 Jill Burke ix © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85162-6 - Artistic Centers of the Italian Renaissance: Florence Edited by Francis Ames-Lewis Table of Contents More information x CONTENTS 8 florence under the medici pontificates, 1513–1537 290 William E. Wallace 9 cosimoiandthearts 330 Elizabeth Pilliod Bibliography 375 Index 413 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85162-6 - Artistic Centers of the Italian Renaissance: Florence Edited by Francis Ames-Lewis Table of Contents More information ILLUSTRATIONS S Color Plates XI Andrea di Cione (Orcagna), Tabernacle, Color plates follow pages xxiv, 120, and 208. Orsanmichele, Florence I Giotto, Crucifix, Santa Maria Novella, XII Anonymous, Episodes from the Lives of Florence Diana and Actaeon (obverse side of II Giotto, Trial by Fire, Bardi Chapel, Santa wooden tray). -

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Mary Magdalene

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Pietro Lorenzetti Sienese, active 1306 - 1345 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Mary Magdalene and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych] probably 1340 tempera on panel transferred to canvas Inscription: middle panel, across the bottom edge, on a fragment of the old frame set into the present one: [PETRUS] L[A]URENTII DE SENIS [ME] PI[N]XIT [ANNO] D[OMI]NI MCCCX...I [1] Gift of Frieda Schiff Warburg in memory of her husband, Felix M. Warburg 1941.5.1.a-c ENTRY The central Madonna and Child of this triptych, which also includes Saint Catherine of Alexandria, with an Angel [right panel] and Saint Mary Magdalene, with an Angel [left panel], proposes a peculiar variant of the so-called Hodegetria type. The Christ child is supported on his mother’s left arm and looks out of the painting directly at the observer, whereas Mary does not point to her son with her right hand, as is usual in similar images, but instead offers him cherries. The child helps himself to the proffered fruit with his left hand, and with his other is about to pop one of them into his mouth. [1] Another unusual feature of the painting is the smock worn by the infant Jesus: it is embellished with a decorative band around the chest; a long, fluttering, pennant-like sleeve (so-called manicottolo); [2] and metal studs around his shoulders. The group of the Madonna and Child is flanked by two female saints. -

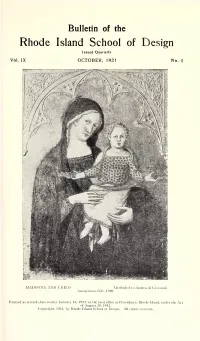

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

Agnolo Gaddi

Frammentiarte.it vi offre l'opera completa ed anche il download in ordine alfabetico per ogni singolo artista Giorgio Vasari - Le vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (1568) Parte prima Agnolo Gaddi VITA D’AGNOLO GADDI PITTOR FIORENTINO Di quanto onore e utile sia l’essere eccellente in un’arte nobile, manifestamente si vide nella virtù e nel governo di Taddeo Gaddi, il quale, essendosi procacciato con la industria e fatiche sue oltre al nome buonissime faccultà, lasciò in modo accomodate le cose della famiglia sua, quando passò all’altra vita, che agevolmente potettono Agnolo e Giovanni suoi figliuoli dar poi principio a grandissime ricchezze et all’esaltazione di casa Gaddi, oggi in Fiorenza nobilissima et in tutta la cristianità molto reputata. E di vero è ben stato ragionevole, avendo ornato Gaddo, Taddeo, Agnolo e Giovanni colla virtù e con l’arte loro molte onorate chiese, che siano poi stati i loro successori dalla S. Chiesa Romana e da’ sommi Pontefici di quella, ornati delle maggiori dignità ecclesiastiche. Taddeo dunque, del quale avemo di sopra scritto la vita, lasciò Agnolo e Giovanni suoi figliuoli in compagnia di molti suoi discepoli, sperando che particolarmente Agnolo dovesse nella pittura eccellentissimo divenire; ma egli, che nella sua giovanezza mostrò volere di gran lunga superare il padre, non riuscì altramente secondo l’openione che già era stata di lui conceputa, perciò che, essendo nato e alevato negl’agi, che sono molte volte d’impedimento agli studii, fu dato più ai traffichi e alle mercanzie che all’arte della pittura. -

![Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7048/madonna-and-child-with-the-blessing-christ-and-saints-peter-james-major-anthony-abbott-and-a-deacon-saint-entire-triptych-c-1997048.webp)

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Martino di Bartolomeo Sienese, active 1393/1434 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [entire triptych] c. 1415/1420 tempera on panel Inscription: middle panel, on Christ's book: Ego S / um lu / x m / undi / [et] via / veritas / et vita / quise / gui ... (I am the light of the world and the way, the truth and the life; a conflation of John 8:12 and 14:6) [1] Gift of Samuel L. Fuller 1950.11.1.a-c ENTRY This triptych's image of the Madonna and Child recalls the type of the Glykophilousa Virgin, the “affectionate Madonna.” She rests her cheek against that of the child, who embraces her. The motif of the child’s hand grasping the hem of the neckline of the Virgin’s dress seems, on the other hand, to allude to the theme of suckling. [1] The saints portrayed are easily identifiable by their attributes: Peter by the keys, as well as by his particular facial type; James Major, by his pilgrim’s staff; Anthony Abbot, by his hospitaller habit and T-shaped staff. [2] But the identity of the deacon martyr saint remains uncertain; he is usually identified as Saint Stephen, though without good reason, as he lacks that saint’s usual attributes. Perhaps the artist did not characterize him with a specific attribute because the triptych was destined for a church dedicated to him. -

Cennino Cennini

Rudolf Kuhn Cennino Cennini Sein Verständnis dessen, was die Kunst in der Malerei sei, und seine Lehre vom Entwurfs- und vom Werkprozeß1 (Zuerst gedruckt in: Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft vol. 36, 1991, 104 – 153; die Seitenumbrüche dieser Druckausgabe sind in Klammern angegeben) Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 3 I. Der Libro dell'Arte ist ein Lehrbuch der Kunst 4 1. Das Lehrbuch der Kunst enthält einen Lehrgang 5 2. Vom Inhalt des Lehrganges der Kunst und die Aufzählung der Aufgaben der Kunst in der Malerei 6 3. Die Länge der Ausbildung eines Künstlers 8 II. Storia und Componere 8 1. Storia 9 2. Componere 10 3. Lehrte Cennini, vorbereitend auf dem Papier zu entwerfen oder zeichnend auf dem Bildträger (Wand oder Tafel)? 12 3,1. Was ergibt sich aus seinem Lehrbuch der Kunst? 12 3,2. Und die erhaltenen Ureinfälle, Skizzen und abschließenden Reinzeichnungen? 14 4. Entwurfsprozess auf dem Bildträger 18 4,1. Der Entwurf auf der Wand 18 4,2. Der Entwurf auf der Tafel 20 5. Hell-dunkel und Farbe 21 5,1. Die sieben Farben 21 5,2. Die Abstufung (digradazione) der Farben sowie des Hell und Dunkels 22 6. Proportionen, Räumliche Verhältnisse, Perspektiven 26 6,1. Die Maßrechnung 26 6,2. Die Frage nach den Proportionen der Körper von Mann, Frau und Tier 27 1 Im Rahmen eines Akademiestipendiums der Stiftung Volkswagen konnte ich u.a. dieses Kapitel einer Abhandlungsfolge fertigstellen. Ich danke der Stiftung Volkswagen dafür sehr. 6,3. Die räumlichen Verhältnisse bei Figur und Storia 27 6,4. Die Perspektive 28 III. Studien 28 1. -

Entire Triptych

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Agnolo Gaddi Florentine, c. 1350 - 1396 Madonna and Child with Saints Andrew, Benedict, Bernard, and Catherine of Alexandria with Angels [entire triptych] shortly before 1387 tempera on poplar panel left panel (overall): 197 × 80 cm (77 9/16 × 31 1/2 in.) middle panel (overall): 204 × 80 cm (80 5/16 × 31 1/2 in.) right panel (overall): 194.6 × 80 cm (76 5/8 × 31 1/2 in.) Inscription: left panel, across the bottom below the saints: S. ANDREAS AP[OSTO]L[U]S; S. BENEDICTUS ABBAS; left panel, on the book held by St. Benedict: AUSCU / LTA.O/ FILI.PR / ECEPTA / .MAGIS / [T]RI.ET.IN / CLINA.AUREM / CORDIS.T / UI[ET]A[D]MONITIONE / M.PII.PA / TRIS.LI / BENTE / R.EXCIP / E.ET.EF[FICACITER COMPLE] (Harken, O son, to the precepts of the master and incline the ear of your heart and willingly receive the admonition of the pious father and efficiently);[1] middle panel, across the bottom: AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS [TECUM] (Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee; from Luke 1:28); middle panel, on the book held by the Redeemer in the gable: EGO SUM / A[ET] O PRINCI / PIU[M] [ET] FINIS / EGO SUM VI / A. VERITAS / [ET] VITA (I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, I am the way, the truth, and the life; from John 14:6; Revelations 22:13); right panel, across the bottom under the saints: S. -

Pittura Gotica

LICEO SCIENTIFICO N. COPERNICO Classe 3AL anno scolastico 2017/2018 LA PITTURA GOTICA Gruppo di lavoro: Calamai Martina Cecchi Giulia Desii Niccolò Incarbona Benedetta Magnini Alessandra prof. Claudio Puccetti LA PITTURA GOTICA LA SCUOLA FIORENTINA CIMABUE GIOTTO LA SCUOLA SENESE DUCCIO DI BUONINSEGNA SIMONE MARTINI AMBROGIO E P I E T R O LORENZETTI Le caratteristiche della pittura gotica Ha un suo spazio Non è subordinata all’architettura Scopo: educare il fedele Temi principalmente sacri (Bibbia) Opere commissionate dal clero Difficile distaccamento iniziale dalla tradizione Maggior naturalismo Attenzione per la figura umana La scuola fiorentina e la scuola senese Corrente fiorentina (Cimabue) Corrente senese (Duccio) Pochi colori, ma contrastanti Colori molto luminosi timbrici e vari Forme disposte per suggerire la Il volume non viene evidenziato profondità Attenzione ai particolari Volume più reale, più fisico Assenza elementi che suggeriscono la Struttura più architettonica profondità Forme più sintetiche Non c’è chiaroscuro Chiaroscuro forte > evidenzia il La linea più libera volume La linea agisce in rapporto al volume CIMABUE (1240 ca – 1302) CIMABUE - Crocifisso Arezzo, Chiesa San Domenico Il corpo si flette, dando maggior senso di volume Volto addolorato e all’orientale Indumento copre le nudità CIMABUE (1240 ca – 1302) CIMABUE (1240 ca – 1302) CIMABUE - Crocifisso Firenze, Chiesa Santa Croce Naturalismo nella posizione Panno quasi trasparente; si intravedono le linee del corpo Novità più accentuate -

Indexes Index of Changes of Attribution

INDEXES INDEX OF CHANGES OF ATTRIBUTION Old Attributioll Kress Number New Attributioll Amadeo da Pistoia KI024 'Alunno di Benozzo,' p. II7, Fig. 320 Amadeo cia Pistoia KI02S 'Alunno di Denozzo,' p. II8, Fig. 319 Andrea da Firenze K263 Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece, p. 29, Fig. 68 Andrea di Giusto K269 Attributed to Vecchietta, p. lSI, Fig. 409 Baldovinetti K402 Pier Francesco Fiorentino, p. II4, Fig. 312 Balduccio, Matteo K222 Girolamo di Benvenuto, p. 162, Fig. 448 Baronzio KI3I2 Master of the Life of St. John the Baptist, p. 68, Fig. 182 Baronzio K264 Master of the Life of St.John the Baptist, p. 69, Fig. 184 Baronzio KI084 Master of the Blessed Clare, p. 70, Fig. 187 Bartolo di Fredi K204S Paolo di Giovanni Fei, p. 62, Fig. IS9 Bartolommeo di Giovanni K77 Master of the 'Apollini Sacrum,' p. 128, Fig. 34S Bartolommeo di Giovanni K79 Master of the 'Apollini Sacrum,' p. 128, Fig. 346 Bartolommeo di Giovanni KI72IA, B Master of the Apollo and Daphne Legend, p. 129, Figs. 347, 349 Cimabue(?) K36r Italian School, c. 1300, p. 6, Fig. II Cimabue (?) K324 Italian School, c. 1300, p. 6, Fig. 12 Cimabue, Contemporary 01 KII89 Tuscan School, Late XIII Century, p. 6, Fig. 8 Cossa, Francesco del K3 87 Ferrarese School, Late XV Century, p. 86, Fig. 236 Daddi, Bernardo KI97 Master of San Martino alla Palma, p. 30, Fig. 71 Daddi, Bernardo, Follower of K263 Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece, p. 29, Fig. 68 Domenico di Michelino KS40 Pesellino and Studio, p. IIO, Fig. 302 Domenico di Michelino KS41 Pesellino and Studio, p.