The Assumption of the Virgin with Busts of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin of the Annunciation C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides Spirituality through Art 2015 Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides Recommended Citation Contis, George M.D., "Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God" (2015). Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides/5 This Exhibit Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Spirituality through Art at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H . Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H. Booklet created for the exhibit: Icons from the George Contis Collection Revelation Cast in Bronze SEPTEMBER 15 – NOVEMBER 13, 2015 Marian Library Gallery University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio 45469-1390 937-229-4214 All artifacts displayed in this booklet are included in the exhibit. The Nativity of Christ Triptych. 1650 AD. The Mother of God is depicted lying on her side on the middle left of this icon. Behind her is the swaddled Christ infant over whom are the heads of two cows. Above the Mother of God are two angels and a radiant star. The side panels have six pairs of busts of saints and angels. Christianity came to Russia in 988 when the ruler of Kiev, Prince Vladimir, converted. -

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Paolo di Giovanni Fei Sienese, c. 1335/1345 - 1411 The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple 1398-1399 tempera on wood transferred to hardboard painted surface: 146.1 × 140.3 cm (57 1/2 × 55 1/4 in.) overall: 147.2 × 140.3 cm (57 15/16 × 55 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.4 ENTRY The legend of the childhood of Mary, mother of Jesus, had been formed at a very early date, as shown by the apocryphal Gospel of James, or Protoevangelium of James (second–third century), which for the first time recounted events in the life of Mary before the Annunciation. The iconography of the presentation of the Virgin that spread in Byzantine art was based on this source. In the West, the episodes of the birth and childhood of the Virgin were known instead through another, later apocryphal source of the eighth–ninth century, attributed to the Evangelist Matthew. [1] According to this account of her childhood, Mary, on reaching the age of three, was taken by her parents, together with offerings, to the Temple of Jerusalem, so that she could be educated there. The child ascended the flight of fifteen steps of the temple to enter the sacred building, where she would continue to live, fed by an angel, until she reached the age of fourteen. [2] The legend linked the child’s ascent to the temple and the flight of fifteen steps in front of it with the number of Gradual Psalms. -

Dositheos Notaras, the Patriarch of Jerusalem (1669-1707), Confronts the Challenges of Modernity

IN SEARCH OF A CONFESSIONAL IDENTITY: DOSITHEOS NOTARAS, THE PATRIARCH OF JERUSALEM (1669-1707), CONFRONTS THE CHALLENGES OF MODERNITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Christopher George Rene IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser Theofanis G. Stavrou SEPTEMBER 2020 © Christopher G Rene, September 2020 i Acknowledgements Without the steadfast support of my teachers, family and friends this dissertation would not have been possible, and I am pleased to have the opportunity to express my deep debt of gratitude and thank them all. I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, who together guided me through to the completion of this dissertation. My adviser Professor Theofanis G. Stavrou provided a resourceful outlet by helping me navigate through administrative channels and stay on course academically. Moreover, he fostered an inviting space for parrhesia with vigorous dialogue and intellectual tenacity on the ideas of identity, modernity, and the role of Patriarch Dositheos. It was in fact Professor Stavrou who many years ago at a Slavic conference broached the idea of an Orthodox Commonwealth that inspired other academics and myself to pursue the topic. Professor Carla Phillips impressed upon me the significance of daily life among the people of Europe during the early modern period (1450-1800). As Professor Phillips’ teaching assistant for a number of years, I witnessed lectures that animated the historical narrative and inspired students to question their own unique sense of historical continuity and discontinuities. Thank you, Professor Phillips, for such a pedagogical example. -

![Iiiilij]M]I~Llij~Lj~Llll]~ 1111 130112 Abb.3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4233/iiiilij-m-i-llij-lj-llll-1111-130112-abb-3-554233.webp)

Iiiilij]M]I~Llij~Lj~Llll]~ 1111 130112 Abb.3

P f ( ; ; c.: ;: f ./ : t', " i l: ." J (J I I t 36. R!p,. IIIIlij]m]I~llij~lj~llll]~ 1111 130112 Abb.3. Meo da Siena, Christ and Apostles Frankfurt, Stadel-Museum NOTES ON TUSCAN PAINTERS OF THE TRECENTO IN THE STAoEL INSTITUT AT FRANKFURT BY B. BERENSON he Stiidel Institut at Frankfurt possesses a number of works by minor masters of the Tuscan TTrecento. Although several have already been published, a systematic account of all of them will scarcely come amiss. It will serve for reference, or help to make them a subject of discourse. The earliest are two panels, Fig. 3 and 4, dated 1333 that must have served as pred elle to the front or back of some altarpiece. Curt Weigelt correctly ascribed them to Meo of Siena 1). In one of the panels Our Lord sits enthroned under a trefle arch between the twelve disciples each of whom stand under a similar arch. In the other Our Lady also sits similarly with angels in attend ance, and the donor, a monk, at her feet. To right and left stand twelve saints each under a trefle arch. Peter returns, but here as Pope, and the other Pope is probably Gregory. It is easy to identify Paul and the Baptist, Stephen and probably Lawrence. The others remain for me anonymous. In the spandrils between the arches busts of angels appear in the predella with Our Lord, and busts of prophets and sibyls in the one of Our Lady. Except David, strumming on a kind of harp, the others are busy unfurling, or reading, or expounding scrolls. -

MEDIEVAL and EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous

MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous (French) Illuminated page from a Psalter in Latin, ca. 1200-1210 Ink, Pigments and gold on parchment 2002.15 Gilbreath-McLorn Fund This page comes from a Psalter, a bound collection of the 150 Psalms, which provided medieval readers with tools for private and communal devotions. Stylistically, this leaf resembles other manuscripts produced in Northeastern France, Paris and England during the reign of the French monarch Philip Augustus (1179-1223). The script is written in a Gothic liturgical hand, and the large illuminated initials and painted line-endings were created at the same time as the text. The Verso linear penwork in-fills and flourishes were probably added after 1250. The high quality of the decoration, together with the lavish use of gold and lapis blue, indicates that this page comes from a book made for a member of the royal court or a high- ranking cleric. (MAA 11/05) Recto MAA 6/2012 Docent Manual Volume 2 Medieval and Early Renaissance 1 MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous (Netherlandish) Adoration of the Magi from a Book of Hours, ca. 1480 Ink, pigments and gold on parchment 2003.1 Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a fashion developed among wealthy Europeans for lavishly illustrated Books of Hours. These manuscripts contained psalms and prayers for recitation and devotions throughout the eight canonical hours of the day. In Books of Hours devoted to the Virgin Mary, an image of The Adoration of the Magi traditionally accompanies the text for sext, to be read during the mid-afternoon. -

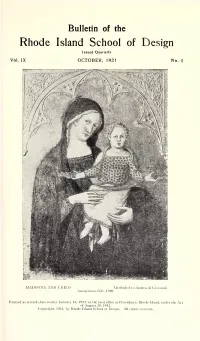

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

The Early Netherlandish Underdrawing Craze and the End of a Connoisseurship Era

Genius disrobed: The Early Netherlandish underdrawing craze and the end of a connoisseurship era Noa Turel In the 1970s, connoisseurship experienced a surprising revival in the study of Early Netherlandish painting. Overshadowed for decades by iconographic studies, traditional inquiries into attribution and quality received a boost from an unexpected source: the Ph.D. research of the Dutch physicist J. R. J. van Asperen de Boer.1 His contribution, summarized in the 1969 article 'Reflectography of Paintings Using an Infrared Vidicon Television System', was the development of a new method for capturing infrared images, which more effectively penetrated paint layers to expose the underdrawing.2 The system he designed, followed by a succession of improved analogue and later digital ones, led to what is nowadays almost unfettered access to the underdrawings of many paintings. Part of a constellation of established and emerging practices of the so-called 'technical investigation' of art, infrared reflectography (IRR) stood out in its rapid dissemination and impact; art historians, especially those charged with the custodianship of important collections of Early Netherlandish easel paintings, were quick to adopt it.3 The access to the underdrawings that IRR afforded was particularly welcome because it seems to somewhat offset the remarkable paucity of extant Netherlandish drawings from the first half of the fifteenth century. The IRR technique propelled rapidly and enhanced a flurry of connoisseurship-oriented scholarship on these Early Netherlandish panels, which, as the earliest extant realistic oil pictures of the Renaissance, are at the basis of Western canon of modern painting. This resulted in an impressive body of new literature in which the evidence of IRR played a significant role.4 In this article I explore the surprising 1 Johan R. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos -

THE BERNARD and MARY BERENSON COLLECTION of EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls

THE BERNARD AND MARY BERENSON COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PAINTINGS AT I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls GENERAL INDEX by Bonnie J. Blackburn Page numbers in italics indicate Albrighi, Luigi, 14, 34, 79, 143–44 Altichiero, 588 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum catalogue entries. (Fig. 12.1) Alunno, Niccolò, 34, 59, 87–92, 618 Angelico (Fra), Virgin of Humility Alcanyiç, Miquel, and Starnina altarpiece for San Francesco, Cagli (no. SK-A-3011), 100 A Ascension (New York, (Milan, Brera, no. 504), 87, 91 Bellini, Giovanni, Virgin and Child Abbocatelli, Pentesilea di Guglielmo Metropolitan Museum altarpiece for San Nicolò, Foligno (nos. 3379 and A3287), 118 n. 4 degli, 574 of Art, no. 1876.10; New (Paris, Louvre, no. 53), 87 Bulgarini, Bartolomeo, Virgin of Abbott, Senda, 14, 43 nn. 17 and 41, 44 York, Hispanic Society of Annunciation for Confraternità Humility (no. A 4002), 193, 194 n. 60, 427, 674 n. 6 America, no. A2031), 527 dell’Annunziata, Perugia (Figs. 22.1, 22.2), 195–96 Abercorn, Duke of, 525 n. 3 Alessandro da Caravaggio, 203 (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale Cima da Conegliano (?), Virgin Aberdeen, Art Gallery Alesso di Benozzo and Gherardo dell’Umbria, no. 169), 92 and Child (no. SK–A 1219), Vecchietta, portable triptych del Fora Crucifixion (Claremont, Pomona 208 n. 14 (no. 4571), 607 Annunciation (App. 1), 536, 539 College Museum of Art, Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion Abraham, Bishop of Suzdal, 419 n. 2, 735 no. P 61.1.9), 92 n. 11 (no. SK-C-1596), 331 Accarigi family, 244 Alexander VI Borgia, Pope, 509, 576 Crucifixion (Foligno, Palazzo Gossaert, Jan, drawing of Hercules Acciaioli, Lorenzo, Bishop of Arezzo, Alexeivich, Alexei, Grand Duke of Arcivescovile), 90 Kills Eurythion (no. -

Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ICONS AND SAINTS OF THE EASTERN ORTHODOX CHURCH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alfredo Tradigo | 384 pages | 01 Sep 2006 | Getty Trust Publications | 9780892368457 | English | Santa Monica CA, United States Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church PDF Book In the Orthodox Church "icons have always been understood as a visible gospel, as a testimony to the great things given man by God the incarnate Logos". Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol —the "red" corner see Icon corner. Guide to Imagery Series. Samuel rated it really liked it Jun 21, It did not disappoint on this detail. Later communion will be available so that one can even utilize the sense of taste during worship. Statues in the round were avoided as being too close to the principal artistic focus of pagan cult practices, as they have continued to be with some small-scale exceptions throughout the history of Eastern Christianity. The Art of the Byzantine Empire — A Guide to Imagery 10 , Bildlexikon der Kunst 9. Parishioners do not sit primly in the pews but may walk throughout the church lighting candles, venerating icons. Modern academic art history considers that, while images may have existed earlier, the tradition can be traced back only as far as the 3rd century, and that the images which survive from Early Christian art often differ greatly from later ones. Aldershot: Ashgate. In the Orthodox Church an icon is a sacred image, a window into heaven. Purple reveals wealth, power and authority. Vladimir's Seminary Press, The stillness of the icon draws us into the quiet so that we can lay aside the cares of this world and meditate on the splendor of the next.