Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage Israëls, M. Publication date 2003 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Israëls, M. (2003). Sassetta's Madonna della Neve. An Image of Patronage. Primavera Pers. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Index Note Page references in bold indicate Avignonese period of the papacy, 108, Bernardino, Saint, 26, 82n, 105 illustrations. 11 in Bertini (family), 3on, 222 - Andrea di Francesco, 19, 21, 30 Abbadia Isola Baccellieri, Baldassare, 15011 - Ascanio, 222 - Abbey of Santi Salvatore e Cirino, Badia Bcrardcnga, 36n - Beatrice di Ascanio, 222, 223 -

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

Construction As Depicted in Western Art Construction As Depicted in Western Art

Tutton Construction Michael Tutton as Depicted in Western Art Construction as Depicted in Western Art Western in Depicted as Construction From Antiquity to the Photograph Construction as Depicted in Western Art Construction as Depicted in Western Art From Antiquity to the Photograph Michael Tutton Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: 1587, German, unknown master, The Tower of Babel, oil or tempera on panel. Z 2249, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 255 0 e-isbn 978 90 4853 259 9 doi 10.5117/9789462982550 nur 684 © M. Tutton / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Catherine, Emma and Samuel Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the following for help and support in producing this book: Catherine Tutton, Emma Tutton, Nicole Blondin, James W P Campbell, David Davidson, Monica Knight, Eleonora Scianna, Catherine Yvard, and my editors at AUP. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 List of Figures 11 Introduction 31 Scope 31 Current Literature and Sources 32 Definitions 33 Layout of the Book 33 1. -

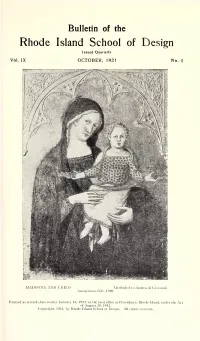

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

The Guido Riccio Controversy in Art History Michael Mallory and Gordon Moran

6 The Guido Riccio controversy in art history Michael Mallory and Gordon Moran Published in Brian Martin (editor), Confronting the Experts (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996), pp. 131-154 Introduction can be challenged both inside and outside The Guido Riccio is a fresco, or wall painting, academia. in the city of Siena in Italy. Guido Riccio is The lengthy duration of the Guido Riccio short for the full name, Guido Riccio da controversy has given us the time and the Fogliano at the Siege of Montemassi. The opportunity to study other academic contro- standard view has long been that Simone versies of the past and present, and to compare Martini, a famous painter from Siena, painted notes with other scholars who are involved in the entire fresco in 1328-1330, a view adopted ongoing disputes of their own. Such compari- by generations of scholars and repeated in sons have enabled us to detect, even predict, many textbooks, guidebooks, reference books, patterns of behaviour on the part of experts as and classroom lectures. This was also our own they attempt to overcome challenges. These view until 1977, when we proposed that a patterns include: the suppression and censor- portion of the fresco, namely the horse and ship of the challengers’ ideas from scholarly rider, was painted by a close follower of conferences, symposia, and journals; personal Simone Martini in 1352, while still attributing attacks, including insults, retaliation, and the rest of the painting to Simone. ostracism, against the challengers; and On the face of it, it would seem that the secrecy, instead of open discussion and debate. -

THE BERNARD and MARY BERENSON COLLECTION of EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls

THE BERNARD AND MARY BERENSON COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PAINTINGS AT I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls GENERAL INDEX by Bonnie J. Blackburn Page numbers in italics indicate Albrighi, Luigi, 14, 34, 79, 143–44 Altichiero, 588 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum catalogue entries. (Fig. 12.1) Alunno, Niccolò, 34, 59, 87–92, 618 Angelico (Fra), Virgin of Humility Alcanyiç, Miquel, and Starnina altarpiece for San Francesco, Cagli (no. SK-A-3011), 100 A Ascension (New York, (Milan, Brera, no. 504), 87, 91 Bellini, Giovanni, Virgin and Child Abbocatelli, Pentesilea di Guglielmo Metropolitan Museum altarpiece for San Nicolò, Foligno (nos. 3379 and A3287), 118 n. 4 degli, 574 of Art, no. 1876.10; New (Paris, Louvre, no. 53), 87 Bulgarini, Bartolomeo, Virgin of Abbott, Senda, 14, 43 nn. 17 and 41, 44 York, Hispanic Society of Annunciation for Confraternità Humility (no. A 4002), 193, 194 n. 60, 427, 674 n. 6 America, no. A2031), 527 dell’Annunziata, Perugia (Figs. 22.1, 22.2), 195–96 Abercorn, Duke of, 525 n. 3 Alessandro da Caravaggio, 203 (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale Cima da Conegliano (?), Virgin Aberdeen, Art Gallery Alesso di Benozzo and Gherardo dell’Umbria, no. 169), 92 and Child (no. SK–A 1219), Vecchietta, portable triptych del Fora Crucifixion (Claremont, Pomona 208 n. 14 (no. 4571), 607 Annunciation (App. 1), 536, 539 College Museum of Art, Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion Abraham, Bishop of Suzdal, 419 n. 2, 735 no. P 61.1.9), 92 n. 11 (no. SK-C-1596), 331 Accarigi family, 244 Alexander VI Borgia, Pope, 509, 576 Crucifixion (Foligno, Palazzo Gossaert, Jan, drawing of Hercules Acciaioli, Lorenzo, Bishop of Arezzo, Alexeivich, Alexei, Grand Duke of Arcivescovile), 90 Kills Eurythion (no. -

Povera E Regale Allo Stesso Tempo

Quotidiano Data 30-03-2013 L’OSSERVATORE ROMANO Pagina 5 Foglio 1 / 2 Il senso iconografico della Madonna dell’umiltà Povera e regale allo stesso tempo Sassetta, «Madonna dell’umiltà» (1435, Musei Vaticani) mentre fa le coccole al piccolo Gesù. Così Masaccio in un di ANTONIO PAOLUCCI celebre piccolo dipinto che sta agli Uffizi, così gli ortodossi nella iconografia della glicofilusa . Ma la Madonna è anche Mater misericordiae , protettrice Papa Francesco nella sua visita a Castel Gandolfo al dai mali del mondo e i pittori hanno voluto darle immagine suo predecessore Benedetto, gli ha portato in regalo un mentre spalanca il mantello a coprire come un’abside di piccolo dipinto raffigurante la Madonna dell’umiltà . chiesa il popolo dei suoi fedeli. Piero della Francesca, al Sono sicuro che molti si sono chiesti qual è il soggetto centro del polittico che si conserva nel Museo civico di iconografico che porta questo titolo. Che cos’è, che cosa Borgo San Sepolcro, ce ne ha consegnato una interpretazione rappresenta la Madonna dell’umiltà ? Per capirlo bisogna tanto celebre quanto insuperata. Anche la Madonna inc inta andare indietro nei secoli e porre mente alle innumerevoli (ancora Piero a Monterchi), la Madonna che ospita nel suo varianti che l’immaginar io popolare, nelle varie epoche e grembo il Corpus Christi e lo presenta all’adorazione del nelle diverse culture, ha voluto dare all’immagine della popolo come la particola consacrata nel ciborio, può essere Madre di Dio. La storia dell’arte ci offre un campionario rappresentata. praticamente infinito di situazioni e quindi di iconografie. I cristiani hanno sempre saputo che la Vergine è Regina E infatti come si può rappresentare la Madonna ? Se lo del Cielo e quindi come una sovrana nella gloria del trono e sono chiesto, generazione dopo generazione, i cristiani e nell’omaggio degli angeli e dei santi deve essere se lo sono chiesto gli artisti che le attese, le idee e i rappresentata. -

Italy, 1200 to 1400

Italy, 1200 to 1400 1 Italy Around 1400 2 Goals • Understand the influence of the Byzantine and classical worlds on the art and architecture. • Understand the rejection of medieval artistic elements and the growing interest in the natural world. • Examine the revival of classical values, in particular, the growth of humanism. • Examine elements of the patronage system that developed at that time, and the patronage rivalries among the developing city states. • Examine the architecture and art as responsive to the growing European power structures at that time. 3 Figure 19-6 Nave of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy, ca. 1246-1470. 4 Let’s Go To Pisa! 5 Figure 17-25 Cathedral complex, Pisa, Italy; cathedral begun 1063; baptistery begun 1153; campanile begun 1174. 6 Rejection of Medieval Artistic Values • Understand the influence of the Byzantine and classical worlds on the art and architecture. • Understand the rejection of medieval artistic elements and the growing interest in the natural world. • Examine the artistic interest in illusionism, pictorial solidity, spatial depth, and emotional display in the human figure. 7 Figure 19-2 NICOLA PISANO, pulpit of the baptistery, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. Marble, 15’ high. 8 Figure 19-3 NICOLA PISANO, Annunciation, Nativity, and Adoration of the Shepherds, relief panel on the baptistery pulpit, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. Marble, 2’ 10” x 3’ 9”. 9 Battle of Romans and barbarians (Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus), from Rome, Italy, ca. 250– 260 CE. Marble, 5’ high. Museo Nazionale Romano-Palazzo Altemps, Rome. 11 Figure 19-3 NICOLA PISANO, Annunciation, Nativity, and Adoration of the Shepherds, relief panel on the baptistery pulpit, Pisa, Italy, 1259–1260. -

Bulgarini, Saint Francis, and the Beginnings of a Tradition

BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Laura Dobrynin June 2006 This thesis entitled BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION by LAURA DOBRYNIN has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Associate Professor of Art History Charles McWeeney Dean, College of Fine Arts DOBRYNIN, LAURA, M.A., June 2006, Art History BULGARINI, SAINT FRANCIS, AND THE BEGINNING OF A TRADITION (110 pp.) Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw This thesis examines the influence of the fourteenth-century Sienese painter Bartolommeo Bulgarini through his depiction of Saint Francis of Assisi exposing his side wound. By tracing the development of this motif from its inception to its dispersal in selected Tuscan panel paintings of the late-1300’s, this paper seeks to prove that Bartolommeo Bulgarini was significant to its formation. In addition this paper will examine the use of punch mark decorations in the works of artists associated with Bulgarini in order to demonstrate that the painter was influential in the dissemination of the motif and the subsequent tradition of its depiction. This research is instrumental in recovering the importance of Bartolommeo Bulgarini in Sienese art history, as well as in establishing further proof of the existence of the hypothesized Sienese “Post-1350” Compagnia, a group of Sienese artists who are thought to have banded together after the bubonic plague of c.1348-50. -

Ministero Per I Beni E Le Attività Culturali Progetto Di Diagnostica Per La Mostra DA JACOPO DELLA QUERCIA a DONATELLO IL PR

Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali Opificio delle Pietre Dure e Laboratori di Restauro di Firenze Viale degli Alfani, 78 50100 Firenze Progetto di diagnostica per la mostra DA JACOPO DELLA QUERCIA A DONATELLO IL PRIMO RINASCIMENTO A SIENA La collaborazione da parte dell’Opificio alla mostra “Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello ‐ Primo Rinascimento a Siena” si inserisce in modo più che perfetto nell’ambito delle ricerche sulle tecniche artistiche, che da tempo affiancano l’attività più propriamente operativa dell’Istituto. Sono state effettuate indagini non invasive su un campione di opere che andranno in mostra (principalmente della Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena), campione estremamente vasto e significativo sia dal punto di vista cronologico che da quello dell’autografia. Si tratta di tecniche di indagine tra le più diffuse nel campo del restauro e della conoscenza dei Beni Culturali, ma che si qualificano, in questo caso, per l’altissima definizione dei risultati (in particolare la Radiografia a lastra unica dell’OPD e la riflettografia InfraRossa ad alta risoluzione dello scanner di OPD e Istituto Nazionale di Ottica CNR di Firenze). Il Settore Dipinti Mobili dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure ha lavorato a questo progetto con passione e grande interesse. Marco Ciatti e Cecilia Frosinini (direttore e vice‐direttore) grazie alle comprovate esperienze nel campo della storia delle tecniche artistiche di Roberto Bellucci e Ciro Castelli, hanno lavorato di stretta intesa con la Pinacoteca di Siena (Annamaria Guiducci ed Elena Pinzauti) alle indagini a più di 30 opere (segue elenco), venendo così a costituire un catalogo parallelo a quello della mostra, dedicato alla tecnica di esecuzione delle botteghe senesi di primo Quattrocento. -

Press Dossier

Press Dossier National Museum of Ancient Art 19 May - 10 September 2017 Nota de prensa This is the first exhibition resulting from the alliance established by ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation and the BPI to implement social and cultural projects in Portugal Madonna. Portugal Presents Treasures from the Vatican Museums • The MNAA, ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation and the BPI present Madonna. Treasures from the Vatican Museums. The exhibition features a selection of works from the famous collections of the Vatican Museums, particularly the extraordinary art gallery. • The show takes visitors on a chronological journey spanning nearly one thousand years, from late Antiquity to the modern age, taking the iconography of Our Lady as its central theme. • The works on show include paintings by “Primitive” Italian artists (Taddeo di Bartolo, Sano de Pietro, Fra Angelico) and great Renaissance and Baroque masters (Rafael, Pinturicchio, Salviati, Pietro da Cortona, Barocci), as well as outstanding tapestries and manuscripts from the Vatican Apostolic Library. • The exhibition is the first fruit from the cultural sponsorship programme established by ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation and the BPI after the two institutions announced their intention to jointly promote social and cultural projects in Portugal over the coming years. Madonna. Treasures from the Vatican Museums . Dates : 19 May - 10 September 2017. Place : National Museum of Ancient Art (R. das Janelas Verdes). Concept and production : ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation, Vatican Museums, National Museum of Ancient Art and BPI. Curators : Alessandra Rodolfo (Vatican Museums) and José Alberto Seabra Carvalho (MNAA). @FundlaCaixa Nota de prensa Lisbon, 16 May 2017. Antônio Filipe Pimentel, director of the National Museum of Ancient Art; Elisa Durán, assistant general manager of ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation; José Pena Amaral, of the BPI Executive Board; and the curators of the exhibition, Alessandra Rodolfo and José Alberto Seabra Carvalho today presented Madonna.