UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multidecadal Climate Variability and the Florescence of Fremont Societies in 2 Eastern Utah

ARTICLE 1 Multidecadal Climate Variability and the Florescence of Fremont Societies in 2 Eastern Utah 3 Judson Byrd Finley , Erick Robinson, R. Justin DeRose, and Elizabeth Hora 4 Fremont societies of the Uinta Basin incorporated domesticates into a foraging lifeway over a 1,000-year period from AD 300 to 5 AD 1300. Fremont research provides a unique opportunity to critically examine the social and ecological processes behind the 6 adoption and abandonment of domesticates by hunter-gatherers. We develop and integrate a 2,115-year precipitation recon- 7 struction with a Bayesian chronological model for the growth of Fremont societies in the Cub Creek reach of Dinosaur National 8 Monument. Comparison of the archaeological chronology with the precipitation record suggests that the florescence of Fremont 9 societies was an adaptation to multidecadal precipitation variability with an approximately 30-plus-year periodicity over most, 10 but not all, of the last 2,115 years. Fremont societies adopted domesticates to enhance their resilience to periodic droughts. We 11 propose that reduced precipitation variability from AD 750 to AD 1050, superimposed over consistent mean precipitation avail- 12 ability, was the tipping point that increased maize production, initiated agricultural intensification, and resulted in increased 13 population and development of pithouse communities. Our study develops a multidecadal/multigenerational model within 14 which to evaluate the strategies underwriting the adoption of domesticates by foragers, the formation of Fremont communities, 15 and the inherent vulnerabilities to resource intensification that implicate the eventual dissolution of those communities. 16 Keywords: Fremont, Uinta Basin, Bayesian modeling, precipitation reconstruction 17 Las sociedades de Fremont de la cuenca de Uinta incorporaron a los domesticados en una forma de vida de alimentación dur- 18 ante un período de 1,000 años desde 300–1300 dC. -

Dinosaur Colorado/Utah

National Monument Dinosaur Colorado/Utah Rock Art As you travel around the Colorado Plateau, you have a great opportunity to discover and leam about the ancient cultures of the region. In the Dinosaur National Monument area, you will find evidence of a group of Native Americans we call the Fremont people, who lived here about 1,000 years ago. The Fremont were not the only early dwellers here; archaeological evidence indicates human occupancy as far back as 8,000 years ago. However, it was the Fremont who left the most visible reminders of their presence, in the form of their rock art. Fremont rock art includes both pictographs (designs created by applying pigment to the rock surface) and petroglyphs (designs chipped or carved into the rock). Pictographs are relatively rare here, perhaps because they are more easily weathered. Most of the rock art in the monument is in the form of petroglyphs, usually found on smooth sandstone cliffs darkened by desert varnish (a naturally-formed stain of iron and manganese oxides). The style and content of Fremont rock art vary throughout the region. In the Uinta Basin, in which most of Dinosaur National Monument lies, the "Classic Vernal Style" predominates. It is characterized by well-executed anthropomorphs (human-like figures), zoomorphs (animal-like figures), and abstract designs. The anthropomorphs typically have trapezoidal bodies, which may or may not include arms, legs, fingers, and toes. They are often elaborately decorated with designs suggesting headdresses, earrings, and necklaces, and they may hold shields or other objects. The zoomorphs include recognizable bighorn sheep, birds, snakes, and lizards, as well as more abstract animal-like shapes. -

(Pdf) Download

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLORADO ROCK ART ASSOCIATION (CRAA) A Chapter of the Colorado Archaeological Society http://www.coloradorockart.org September 2016 Volume 7, Issue 7 As Colorado Rock Art Association members you are also Inside This Issue members of the Colorado Archaeological Society. The Colorado Archaeological Society is having its annual Field Trips …………..….… page 2 meeting October 7-10 in Grand Junction. There will be many field trips, including many that include rock art. In addition, there will be lectures aimed at the avocational Feature Article: The audience. CRAA is sponsoring noted rock art specialist Mu:kwitsi/Hopi (Fremont) Sally Cole. In addition, the Keynote speaker is Steve Lekson who will talk about Chaco Canyon. Steve Lekson is abandonment and Numic a noted Southwest Archaeologist. He is a professor at Immigrants into Nine Mile Colorado University and a curator at the University of Canyon as depicted in the Colorado Museum of Natural History. He has written several books including Chaco Meridian: One Thousand rock art. Years of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest (second ………………………………….…..page 4 edition)(2015) and A History of the Ancient Southwest (2009). Please consider signing up for the annual meeting. Information on how to do sign up is in this issue. Sign up for CAS Annual meeting and other conferences This month’s feature article is part 2 of The Mu:kwitsi/Hopi …………………………….…..…. page 3 (Fremont) abandonment and Numic Immigrants into Nine Mile Canyon as depicted in the rock art, written by CRAA member Carol Patterson. PAAC Fall Classes The new Assistant State Archaeologist Chris Johnston has …………………………………page 12 announced PAAC Classes for this fall around the state. -

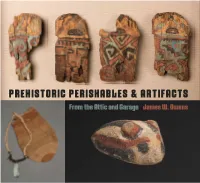

Prehistoric Perishables & Artifacts

PREHISTORIC PERISHABbES I ARTIFACTS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. PREHISTORIC PERISHABLES & ARTIFACTS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 1 6/28/19 10:54 AM Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 2 6/28/19 10:54 AM PREHISTORIC PERISHABLES & ARTIFACTS From the Attic and Garage JAMES W. OWENS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 3 6/28/19 10:54 AM Privately published by James W. Owens Albuquerque, New Mexico and Casper, Wyoming Copyright © !"#$ James W. Owens %&& '()*+, '-,-'.-/ Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 4 6/28/19 10:54 AM Dedicated to Clifford A. Owens 0%+*-' Elaine Day Stewart 12+*-' Helen Snyder Owens ,+-312+*-' Without whom this book would not have been possible. Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 5 6/28/19 10:54 AM Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 6 6/28/19 10:54 AM CONTENTS Preface ix %//(+(2;%& (+-1, : Acknowledgments xii Jewelry ##6 Location, Location, Location # %//(+(2;%& (+-1, < Hohokam #76 /(,3&%4 5%,- # Painted Objects 6 %//(+(2;%& (+-1, $ Hogup Cave #97 /(,3&%4 5%,- ! Hunting Objects !7 %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #" Fremont #:: /(,3&%4 5%,- 7 Cache Pots and Cradleboard 8# %//(+(2;%& (+-1, ## Baskets #<$ /(,3&%4 5%,- 8 Footwear and Accessories 9# %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #! Various Items !": /(,3&%4 5%,- 6 Fremont Items :: %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #7 Pottery !77 /(,3&%4 5%,- 9 Ceremonial Objects $$ Bibliography !67 Permission to copy images denied without written approval. -

Iuc5 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY

uuO I iuc5G NO. 1US GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau Robert G. Campbell i II No. 11 March 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Grover E. Murray, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Clint Formby (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jr., Bill E. Collins, John J. Hinchey, A. J. Kemp, Jr., Robert L. Pfluger, Charles G. Scruggs, Judson F. Williams, and Don R. Workman. l'olic C mmiiiiicc.--J. Knox Jones,Academic Jr. (Chairman. Pidlicatio Dilford C. P Carter (Executive Director), C. Leonard Ainsworth, Frank B. Conselman, Samuel F. Curl. Hugh H. Genoways, Ray C. Janeway, William R. Johnson, S. M. Kennedy, Thomas A. Langford. George F. Meenaghan, Harley D. Oberhclman, Robert L. Packard, and Charles W. Sargent. Graduate Studies No. 11 118 pp. 5 March 1976 $3.00 Graduate Studies are numbered separately and published on an irregular basis under the auspices of the Dean of the Graduate School and Director of Academic Publications, and in cooperation with the International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies. Copies may be obtained on an exchange basis from, or purchased through, the Exchange Librarian, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409. V Texas Tech Press, Lubbock. Texas 1976 GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY The Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau Robert G. Campbell No. 11 March 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Grover E. Murray, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Clint Formby (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jr., Bill E. Collins, John J. Hinchey, A. J. Kemp, Jr., Robert L. Pfluger, Charles G. Scruggs, Judson F. -

Paisaje Y Arquitectura Tradicional Del Noreste De México

Paisaje y arquitectura tradicional del noreste de México Un enfoque ambiental Esperanza García López Dr. Salvador Vega y León Rector General M. en C.Q. Norberto Manjarrez Álvarez Secretario General UNIDAD CUAJIMALPA Dr. Eduardo Abel Peñalosa Castro Rector Dra. Caridad García Hernández Secretaria Académica Dra. Esperanza García López Directora de la División de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Diseño Mtro. Raúl Roydeen García Aguilar Secretario Académico de la División de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Diseño Comité Editorial Mtra. Nora A. Morales Zaragoza Mtro. Jorge Suárez Coéllar Dr. Santiago Negrete Yankelevich Dra. Alejandra Osorio Olave Dr. J. Sergio Zepeda Hernández Dra. Eska Elena Solano Meneses Paisaje y arquitectura tradicional del noreste de México Un enfoque ambiental Esperanza García López Clasificación Dewey: 304.2097217 Clasificación LC: GF91.M6 García López, Esperanza Paisaje y arquitectura tradicional del noroeste de México : un enfoque ambiental / Esperanza García López . -- México : UAM, Unidad Cuajimalpa, División de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Diseño, 2015. 158 p. 15 x 21.5 cm. ISBN: 978-607-28-0619-1 I. Ecología humana – Evaluación del paisaje – México Norte II. México Norte – Condiciones ambientales – Siglo XX-XXI III. México Norte – Descripciones y viajes – Siglo XX-XXI IV. México Norte – Usos y costumbres – Siglo XX-XXI V. Arquitectura mexicana – Historia – Siglo XX-XXI VI. Indígenas de México – Historia Paisaje y arquitectura tradicional del noreste de México. Un enfoque ambiental Esperanza García López Primera edición, 2015. D.R. © Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Cuajimalpa División de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Diseño Avenida Vasco de Quiroga #4871, Colonia Santa Fe Cuajimalpa, Delegación Cuajimalpa, C.P: 05300 México D.F. -

(Pdf) Download

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLORADO ROCK ART ASSOCIATION (CRAA) A Chapter of the Colorado Archaeological Society http://www.coloradorockart.org August 2016 Volume 7, Issue 6 A group of seven us enjoyed a field trip to Sweetwater Inside This Issue Cave last month. Sweetwater cave has pictographs from the historic Ute. It was nice to enjoy rock art in the middle Field Trips …………..….… page 2 of the summer in a nice cool cave. You can see us at the cave in a photo published in this issue. Feature Article: The As Colorado Rock Art Association members you are also Mu:kwitsi/Hopi (Fremont) members of the Colorado Archaeological Society. The Colorado Archaeological Society is having its annual abandonment and Numic meeting October 7-10 in Grand Junction. There will be Immigrants into Nine Mile many field trips, including many that include rock art. In Canyon as depicted in the addition, there will be lectures aimed at the avocational audience. A special lecture sponsored by CRAA is noted rock art. rock art specialist Sally Cole. In addition, the Keynote ………………………………….…..page 3 speaker is Steve Lekson who will talk about Chaco Canyon. Please consider signing up for the annual meeting. Information on how to do sign up is in this issue. PAAC Fall Classes …………………………………page 12 This month’s feature article is by CRAA member Dr. Carol Patterson on The Mu:kwitsi/Hopi (Fremont) abandonment and Numic Immigrants into Nine Mile Canyon as depicted Sign up for CAS Annual in the rock art. Nine Mile Canyon is a well-known, meeting and other conferences extensive rock art site in Utah. -

Human Securities, Sustainability, and Migration in the Ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest

Copyright © 2021 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Ingram, S. E., and S. M. Patrick. 2021. Human securities, sustainability, and migration in the ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest. Ecology and Society 26(2):9. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12312-260209 Synthesis Human securities, sustainability, and migration in the ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest Scott E. Ingram 1 and Shelby M. Patrick 2 ABSTRACT. In the U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest region, arid-lands agriculturalists practiced sedentary agriculture for at least four thousand years. People developed diverse lifeways and a repertoire of successful dryland strategies that resemble those of some small-scale agriculturalists today. A multi-millennial trajectory of variable population growth ended during the early 1300s CE and by the late 1400s population levels in the region declined by about one-half. Here we show, through a meta-analysis of sub-regional archaeological studies, the spatial distribution, intensity, and variation in social and environmental conditions throughout the region prior to depopulation. We also find that as these conditions, identified as human insecurities by the UN Development Programme, worsened, the speed of depopulation increased. Although these conditions have been documented within some sub-regions, the aggregate weight and distribution of these insecurities throughout the Southwest/Northwest region were previously unrecognized. Population decline was not the result of a single disturbance, such as drought, to the regional system; it was a spatially patterned, multi-generational decline in human security. Results support the UN’s emphasis on increasing human security as a pathway toward sustainable development and lessening forced migration. -

The Nature of Prehistory

The Nature of Prehistory In Colorado, mountains ascended past clouds and were eroded to valleys, salty seas flooded our land and were dried to powder or rested on us as freshwater ice, plants rose from wet algae to dry forests and flowers, animals transformed from a single cell to frantic dinosaurs and later, having rotated around a genetic rocket, into sly mammals. No human saw this until a time so very recent that we were the latest model of Homo sapiens and already isolated from much of the terror of that natural world by our human cultures' perceptual permutations and re flections. We people came late to Colorado. The first humans, in the over one hundred thousand square miles of what we now call Colorado, saw a landscape partitioned not by political fences or the orthogonal architecture of wall, floor, and roadway, but by gradations in game abundance, time to water, the supply of burnables, shelter from vagaries of atmosphere and spirit, and a pedestrian's rubric of distance and season. We people came as foragers and hunters to Colorado. We have lived here only for some one hundred fifty centuries-not a long time when compared to the fifty thousand centuries that the Euro pean, African, and Asian land masses have had us and our immediate prehuman ancestors. It is not long compared to the fifty million cen turies of life on the planet. We humans, even the earliest prehistoric The Na ture of Prehistory 3 societies, are all colonists in Colorado. And, except for the recent pass ing of a mascara of ice and rain, we have not been here long enough to see, or study, her changing face. -

Table of Contents

University of Nevada, Reno Moving beyond Boundaries: Fremont and Anasazi Archaeology and Rock Art in Southeastern Utah A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology by Leticia A. Neal Dr. Gary Haynes/Thesis Advisor May, 2010 © by Leticia A. Neal 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by LETICIA A. NEAL entitled Moving beyond Boundaries: Fremont and Anasazi Archaeology and Rock Art in Southeastern Utah be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Gary Haynes, Ph.D., Advisor Catherine S. Fowler, Ph.D., Committee Member Paul Starrs, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2010 i ABSTRACT Southeastern Utah was occupied by groups for whom movement, abandonment, and resettlement was a way of life. Although the Fremont and the Anasazi are often conceptualized as distinct cultural traditions, underlying similarities in lifeways are embodied in their use and conception of the landscape in the Moab area. The Colorado River is often used to demarcate the boundary between the Fremont and the Anasazi. Generally, Fremont rock art styles and sites are located north of the Colorado River, while Anasazi rock art styles and sites are south of the Colorado River. The distribution of Anasazi and Fremont sites, ceramics, and rock art imagery indicate social interaction and a fluctuating border as people, pots, and rock art imagery moved across this frontier. Rock art, in conjunction with other lines of archaeological evidence, provides a unique opportunity to explore the dynamic relationships among communities. -

Chase Orchard: a Potiil Phase Pueblo in the Cimarron District, Northeastern New Mexico with a Suggested Reconstruction of Tanoan Origins and Migrations

Chase Orchard: A Potiil Phase Pueblo in the Cimarron District, Northeastern New Mexico with a Suggested Reconstruction of Tanoan Origins and Migrations James A. Gunnerson with an Appendix on Faunal Remains by R. George Corner Memoir 11 of the Oklahoma Anthropological Society Robert E. Bell Monographs in Anthropology 4 of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History 2007 · Chase Orchard: A Poiiil Phase Pueblo in the Cimarron District, Northeastern New Mexico with a Suggested Reconstruction of Tanoan Origins and Migrations James A. Gunnerson with an Appendix on Faunal Remains by R. George Corner Memoir 11 of the Oklahoma Anthropological Society Robert E. Bell Monographs in Anthropology 4 of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History 2007 Copyright 2007 Oklahoma Anthropological Society Jon Denton Secretary, Oklahoma Anthropological Society Newcastle, Oklahoma This volume formatted in InDesign and edited by Don G. Wyckoff Memoir Editor, Oklahoma Anthropological Society Table of Contents Page Preface ......................................................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... ii A Dedication by Dr. James H. Gunnerson ................................................................................................................ iii The Chase Orchard Pueblo Site Introduction -

American Archaeologywinter 2013-14 a Quarterly Publication of the Archaeological Conservancy Vol

INVESTIGATING 19TH-CENTURY MINING sA LEGENDARY ARCHAEOLOGIST sINSIDE A CIVIL WAR PRISON american archaeologyWINTER 2013-14 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 17 No. 4 PLAYINGPLAYING ANCIENTANCIENT GAMESGAMES $3.95 WINTER 2013-14 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 17 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 12 THE GAMES PEOPLE PLAYED BY ALEXANDRA WITZE What did ancient people do once the day’s work was done? They played games. 19 REINTERPRETING AN ANCIENT ISLAND BY LINDA MARSA A research project on California’s Santa Catalina Island is using ethnographic evidence and sophisticated technology to develop new interpretations of the island’s past. 24 LIFE IN THE WORLD’S LARGEST PRISON CAMP BY MIKE TONER Archaeologists are discovering what took place in Camp Lawton, a huge Civil War prison. 32 WHEN COPPER WAS KING BY CHRISTIE BLECK The Cliff Mine in Michigan’s remote Upper Peninsula triggered a copper boom in the mid-19th century. Archaeologists are investigating the mine to understand how it happened. 39 THE BEST OF HER PROFESSION BY KRISTIN OHLSON Linda Cordell excelled at many things during her long career in archaeology. 44 new acquisition ELEVEN THOUSAND YEARS OF HISTORY The Conservancy’s first site in South Carolina contains one of the oldest known features in the state. 45 new acquisition ARCHAIC SITE SAVED THROUGH PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP Sopris is one of the few Archaic sites in the region. james snead 39 46 point acquisition 48 point acquisition RENOWNED BURIAL SITE PRESERVED LEARNING ABOUT THE MOHAWK The Conservancy is in the process of obtaining the famous The Conservancy acquires the Cayadutta site.