Frost, Gregory T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multilingualism in the Fet Band Schools of Polokwane Area, a Myth Or a Reality

MULTILINGUALISM IN THE FET BAND SCHOOLS OF POLOKWANE AREA, A MYTH OR A REALITY BY MOGODI NTSOANE (2002O8445) SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE; MASTER OF EDUCATION IN LANGUAGE EDUCATION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LIMPOPO, SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUPERVISOR: MONA M.J (MR.) UNIVERSITY OF LIMPOPO PRIVATE BAG X 1106 SOVENGA 0727 LIMPOPO PROVINCE SOUTH AFRICA CHAPTER ONE 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LANGUAGE PROBLEM IN SOUTH AFRICA Extract Language prejudice is of two types: positive and negative. Negative prejudice is image effacing. It is characterized by negative evaluation of one’s own language or speech patterns and a preference for someone else’s. An example of this kind of self- -denigration is the case of David Christiaan, the Nama Chief in Namibia, who, in response to the Dutch missionaries’ attempt to open schools that would conduct their teaching using Nama as a medium of instruction, is reported to have shouted, “Only Dutch, Dutch only! I despise myself and I want to hide in the bush when I am talking my Hottentot language” (Vedder, 1981: 275 as quoted in Ohly, 1992:65. In Ambrose, et al (eds.) undated: 15). 1.1.1 Introduction The South African Constitution (1996) and the Language-in-Education Policy (1997) have declared the eleven languages spoken in the country as official. Despite this directive, it remains questionable when it comes to the issue of the language of instruction and indigenous languages in schools. In most cases, the language of instruction becomes an issue with new governments that come into offices in countries that are multilingual. -

LIFE and WORK in the BANANA FINCAS of the NORTH COAST of HONDURAS, 1944-1957 a Dissertation

CAMPEÑAS, CAMPEÑOS Y COMPAÑEROS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda January 2011 © 2011 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda CAMPEÑAS Y CAMPEÑOS: LIFE AND WORK IN THE BANANA FINCAS OF THE NORTH COAST OF HONDURAS, 1944-1957 Suyapa Gricelda Portillo Villeda, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 On May 1st, 1954 banana workers on the North Coast of Honduras brought the regional economy to a standstill in the biggest labor strike ever to influence Honduras, which invigorated the labor movement and reverberated throughout the country. This dissertation examines the experiences of campeños and campeñas, men and women who lived and worked in the banana fincas (plantations) of the Tela Railroad Company, a subsidiary of the United Fruit Company, and the Standard Fruit Company in the period leading up to the strike of 1954. It describes the lives, work, and relationships of agricultural workers in the North Coast during the period, traces the development of the labor movement, and explores the formation of a banana worker identity and culture that influenced labor and politics at the national level. This study focuses on the years 1944-1957, a period of political reform, growing dissent against the Tiburcio Carías Andino dictatorship, and worker agency and resistance against companies' control over workers and the North Coast banana regions dominated by U.S. companies. Actions and organizing among many unheralded banana finca workers consolidated the powerful general strike and brought about national outcomes in its aftermath, including the state's institution of the labor code and Ministry of Labor. -

South Africa

<*x>&&<>Q&$>ee$>Q4><><>&&i<>4><><i^^ South Africa UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA HE political tension of the previous three years in the Union of South TAfrica (see articles on South Africa in the AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, Vols. 51, 52 and 53) broke, during the period under review, into a major constitutional crisis. A struggle began between the legislature and the judi- ciary over the "entrenched clauses" of the South Africa Act, which estab- lished the Union, and over the validity of a law passed last year by Daniel Francois Malan's Nationalist Government to restrict the franchise of "Col- ored" voters in Cape Province in contravention of these provisions. Simul- taneously, non-European (nonwhite) representative bodies started a passive resistance campaign against racially discriminatory legislation enacted by the present and previous South African governments. Resulting unsettled condi- tions in the country combined with world-wide economic trends to produce signs of economic contraction in the Union. The developing political and racial crisis brought foreign correspondents to report at first hand upon conditions in South Africa. Not all their reports were objective: some were characterized by exaggeration and distortion, and some by incorrect data. This applied particularly to charges of Nationalist anti-Semitism made in some reports. E. J. Horwitz, chairman of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies (central representative body of South Afri- can Jewry) in an interview published in Die Transvaler of May 16, 1952, specifically refuted as "devoid of all truth" allegations of such anti-Semitism, made on May 5, 1952, in the American news magazine Time. -

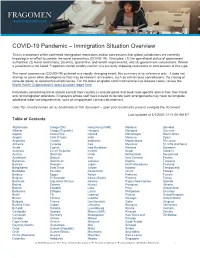

Immigration Situation Overview

COVID-19 Pandemic – Immigration Situation Overview This is a summary of the confirmed immigration restrictions and/or concessions that global jurisdictions are currently imposing in an effort to contain the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). It includes: (1) the operational status of government authorities; (2) travel restrictions; (3) entry, quarantine, and health requirements; and (4) government concessions. Where a jurisdiction is not listed, Fragomen cannot reliably confirm it is currently imposing restrictions or concessions of this type. The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak is a rapidly changing event; this summary is for reference only. It does not attempt to cover other developments that may be relevant to travelers, such as airline route cancellations, the closing of consular posts, or national travel advisories. For the latest on global confirmed coronavirus disease cases, review the World Health Organization’s latest situation report here. Individuals considering travel should consult their country’s consular posts and seek case-specific advice from their travel and /or immigration providers. Employers whose staff have moved to remote work arrangements may need to complete additional labor law requirements, such as employment contract amendment. User Tip: country names act as bookmarks in this document – open your bookmarks pane to navigate the document. Last updated at 6/1/2020 11:11:00 AM ET Table of Contents Afghanistan Congo (DR) Hong Kong (SAR) Moldova Slovakia Albania Congo (Republic) Hungary Mongolia Slovenia Algeria -

The Perpetual Motion Machine: National Co-Ordinating Structures and Strategies Addressing Gender-Based Violence in South Africa

THE PERPETUAL MOTION MACHINE: NATIONAL CO-ORDINATING STRUCTURES AND STRATEGIES ADDRESSING GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE IN SOUTH AFRICA A MISTRA WORKING PAPER 11 August 2021 Lisa Vetten Lisa Vetten is a research/project consultant in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg and a research associate of the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies based at the University of the Witwatersrand. Her work on gendered forms of violence has ranged across the NGO sector, academia and the bureaucracy, and has encompassed counselling, research and policy development. Abstract Violence, and the ways it is gendered, have long constituted a serious problem in South Africa. In 2000, Cabinet set up the first coordinating structure tasked with developing a plan to combat this violence, and, since 2011, there has been an expanding apparatus of structures, institutions and processes around GBV. They have, however, been founded in a set of generic – even formulaic – prescriptions that ignore the current state of the South African state. As such, the many plans and structures that constitute the machinery to address GBV are characterised by hasty, ad hoc institutional design, unaccountability and wasted endeavour. Contrasting with these managerial processes, are the anger and grief experienced by the many individuals whose lives are affected by GBV. While this has manifested in the proliferation of popular protest by women’s organisations and other formations demanding action from the state, it has not resulted in a disruption to the myriad processes and institutions that constitute the governance machinery surrounding GBV. Struggles between women within the sector have instead resulted in a politics of bad blood which, while not the sum total of the sector’s politics, works in ways that are powerfully divisive. -

(IPADA) Conference Proceedings 2017

Conference Proceedings Published by the INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND DEVELOPMENT ALTERNATIVES (IPADA) The 2nd Annual Conference on ‛‛ The Independence of African States in the Age of Globalisation” ISBN: 978-620-73782-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-620-73783-8 (e-book) EDITORS Prof MP Sebola, University of Limpopo Prof JP Tsheola, University of Limpopo Tlotlo Hotel and Conference Centre, Gaborone, Botswana July 26-28, 2017 Editorial Committee Prof MP Sebola, University of Limpopo Dr RM Mukonza, Tshwane University of Technology Dr KB Dipholo, University of Botswana Dr YF April, Human Sciences Research Council Dr KN Motubatse, Tshwane University of Technology Editorial Board Prof SR Malefane, University of South Africa Dr B Mothusi, University of Botswana Dr MDJ Matshabaphala, University of Witwatersrand Prof CC Ngwakwe, University of Limpopo Prof O Mtapuri, University of KwaZulu-Natal Dr LB Mzini, North West University Prof L de W Fourie, Unitech of New Zealand Prof M Marobela, University of Botswana Prof BC Basheka, Uganda Technology and Management University Dr RB Namara, Uganda Management Institute Dr M. Maleka, Tshwane University of Technology Prof KO Odeku, University of Limpopo Prof RS Masango, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Prof O Fatoki, University of Limpopo Dr S Kyohairwe, Uganda Management Institute Dr A Asha, University of Limpopo Dr J Coetzee, Polytechnic of Namibia Dr MT Makhura, Land Bank of South Africa Prof Jumbo, University of Venda Dr E Bwalya, University of Botswana Prof EK, Botlhale, University -

Deadly Delay: South Africa's Efforts to Prevent HIV in Survivors of Sexual Violence

Human Rights Watch March 2004, Vol. 16, No. 3 (A) Deadly Delay: South Africa's Efforts to Prevent HIV in Survivors of Sexual Violence I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 3 To the Government of South Africa..................................................................................... 3 Institutional and Programmatic Measures ........................................................................ 3 Legal and Policy Measures .................................................................................................. 5 To Donors and Regional and International Organizations ........................................... 7 III. Methods................................................................................................................................... 7 IV. Background: HIV/AIDS and Sexual Violence in South Africa...................................... 8 HIV/AIDS in South Africa .................................................................................................... 8 Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in South Africa.............................................. 9 The Role of Gender-Specific Violence in HIV Transmission.........................................11 Preventing HIV After Sexual Violence Through HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis....13 Antiretroviral Drug -

Shaping the Future of Africa with the People 1 Declarations and Resolutions

2015 Johannesburg SHAPING THE FUTURE OF AF2015RICA JOHANNESBURG WITH | SHAPING THE THE FUTURE PEOPLE OF AFRICA WITH THE PEOPLE i The 7th edition of the Africities Summit took place at the Sandton Convention Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa from 29 November to 3 December 2015. The Summit was convened by the United Cities and Local Governments of Africa and hosted by the City of Johannesburg, the South African Local Government Association and the South African Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. This report has been compiled by the South African Cities Network. cooperative governance Department: Cooperative Governance REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Contents Declarations and Resolutions 2 PART 1 Introduction 3 1.1 The African Context 4 PART 2 Overview of Africities 7 2.1 Theme of Africities 7 Summit 8 2.2 Objectives of Africities 7 9 2.3 Africities 7 Sessions 9 2.4 The 12 Lessons of Africities 10 PART 3 The Speeches 13 PART 4 Achieving the Future of Agenda 2063 42 4.1 Exploration of Possible Futures 43 4.2 The Formulation of Strategies 45 PART 5 The Contribution of African Local Governments to Achieving the Agenda 2063 49 5.1 Challenges and Opportunities 49 5.2 Women’s Voices on the Implementation of the Agenda 2063 53 5.3 Tripartite Discussion 54 5.4 Political Resolutions and Commitments 56 5.5 Concluding Resolutions 57 5.6 Other Declarations 61 PART 6 Experience of Local Government and Partners 65 6.1 The South African Cities Network (SACN) Sessions 65 6.2 UCLG Africa Sessions 80 6.3 Stakeholder Sessions 99 6.4 Partner -

A1132-C270-001-Jpeg.Pdf

faJUtl&fp j y ^ V No. 4 ' Weekly Edition REPU^lC OF SOUTH AFRICA ^ HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY DEBATES (HAN S ARsQ) THIRD SESSION — THIRD PARLIAMENT 26th FEBRUARY to 1st MARCH, 1968 The sign * indicates that the speech was delivered in Afrikaans and then translated. Where both official languages are used in the same ministerial speech, t indicates the original and * the translated version. CONTENTS Stages of Bills taken without debate are not indicated below COL. NO. COL. NO. M onday, 26th February Births, Marriages and Deaths Registra tion Amendment Bill—Second Human Sciences Research Bill—Com Reading ............................................ 1220 mittee ............................................... 1119 Wine and Spirits Control Amendment Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amend Bill—Second Reading ..................... 1229 ment Bill—Third Reading .............. 1120 Bantu Administration by Local Authori Indians Advanced Technical Education ties—Motion .................................... 1231 Bill—Committee ............................. 1123 South African Indian Council Bill—Sec W ednesday, 28th F ebruary ond Reading.................................... 1124 Report of Commission of Enquiry into Wine. Other Fermented Beverages and Improper Political Interference and Spirits Amendment Bill—Second Political Representation of the Reading............................................ 1156 Various Population Group s— Waterval River (Lydenburg) Bill—Sec Motion ............................................. 1265 ond Reading ................................... -

Travel Document Information Guide

EU Letters must be completed to the highest standard every time. High quality applications with supporting evidence offer the best opportunity for a successful outcome. WITH WITH MINIMUM ETD / EUL WITH COUNTRY EUL or ETD Column redacted CURRENT COUNTRY INFORMATION Column redacted ORIGINAL COPY ETD VALID FOR Column redacted Column redacted REQUIREMENTS NO EVIDENCE EVIDENCE EVIDENCE AFGHANISTAN EUL Please refer to guidance on the CROS website, providing instruction on the completion of an EUL. Where you have a documentation query regarding an EUL country or a barrier to the use of an EUL has been identified, please contact CROS (telephone number redacted) ALBANIA EUL Please refer to guidance on the CROS website, providing instruction on the completion of an EUL. Where you have a documentation query regarding an EUL country or a barrier to the use of an EUL has been identified, please contact CROS (telephone number redacted) Submission Letter to accompany ETD application 6 Passport photographs 2 Algerian Application forms to be completed in English and Arabic or French Arrest and Detention form for all detained cases only (under the section 'reasons for arrest' state 'immigration offence' or 'to effect deportation') Algeria specific Bio-data Clear copy or original fingerprints Verification checks are completed in country unless 2 to 4 weeks approximately Supporting evidence, if available, to include original or copy of expired the application pack contains an original expired 6-12 months for no with original expired passport, 3 months approximately with passport, military card, ID card, family book, driving license, birth passport, ID card or military card where it would be supporting evidence, military card or ID card. -

Overthrow Kinzer.Pdf

NATIONAL BESTSELLER "A detailed, I)assionateandconvincingbook ... [wilh] lhe pace and grip ofagood lhriller." - TheNew York Tillles BookReview STEPHEN KINZER AUTHOR OF ALL THE SHAH'S MEN OVERTHROW ___________4 _____ 4 __ 111_11 __iii _2_~ __11 __ __ AMERICA'S CENTURY OF REGIME CHANGE FROM HAWAII TO IRAQ STEPHEN KINZER TIM E S BOO K S Henry Holt and Company New York Times Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com Henry Holt® is a registered trademark of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 2006 by Stephen Kinzer All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kinzer, Stephen. Overthrow: America's century of regime change from Hawaii to Iraq I Stephen Kinzer. -1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-8240-1 ISBN-1O: 0-8050-8240-9 1. United States-Foreign relations-20th century. 2. Hawaii-History Overthrow of the Monarchy, 1893.3. Iraq War, 2003- 4. Intervention (Internationallaw)-History-20th century. 5. Legitimacy of governments-History-20th century. I. Title. E744.K49 2006 327. 73009-dc22 2005054856 Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. Originally published in hardcover in 2006 by Times Books First Paperback Edition 2007 Designed by Kelly S. Too Printed in the United States of America 791086 Time present and time past Are both perhaps present in time future, And time future contained in time past. -T. -

Latin America Relations After the Inevitable US Military Intervention In

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN U.S. – Latin America relations after the inevitable U.S. Military intervention in Guatemala in 1954 Relaciones Estados Unidos - América Latina después de la inevitable intervención militar norteamericana de 1954 en Guatemala Fecha de recepción: Agosto de 2014 Fecha de aceptación: Septiembre de 2014 Gianmarco Vassalli MA in International Cooperation for Development of Universidad de San Buenaventura, Cartagena in agreement with the University of Pavia and BA International Relations with Business Dirección postal: Calle Portobello, San Diego C38 10-15, Apt. B13, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia Correo electrónico: [email protected] Revista INTERNACIONAL de COOPERACIÓN y DESARROLLO VOL. 1, NÚM. 2. ISSN (online): 2382-5014 JULIO – DICIEMBRE, 2014 195 U.S. – LATIN AMERICA RELATIONS AFTER THE INEVITABLE U.S. MILITARY INTERVENTION IN GUATEMALA IN 1954 Abstract The 1954 U.S. intervention in Guatemala is a controversial key matter that still finds different and opposing interpretations in academia. In this article the impact of the U.S. coup in Guatemala on U.S.- Central America socio-political relations will be evaluated, through the critical analysis of different perspectives and attributes on the subject. This work identifies, with reference to academic theories, key motives and interests behind the intervention, in relation to the significance of Guatemalan democratic president Jacopo Arbenz’ s reforms in the wider social context of Central America. The possible wide-scale impact of these reforms with the creation of viable alternative model to American liberal capitalism and consequently of a perceivable potential threat to U.S. intrinsic interests in its hemisphere, will be reflectively explored throughout with the intent of proposing a solution over the 1954 U.S.