The Imperial Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, Whose Conspiracy Led to the Assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J

SWAPNIL SANSAR, ENGLISH WEEKLY,LUCKNOW, 21,MARCH, (07) Sukhdev Thapar, Freeom Fighter Sukhdev Thapar was an revolutionary. He was a senior member of Hindustan in New Delhi (8th April 1929), Sukhdev and his accomplices have been arrest - Socialist Republican Association. He was hanged on 23 March1931 at the age ed and convicted of their crime, going through the loss of life sentence as the of 23.Sukhdev Thapar, born (15 May 1907) in Ludhiana, Punjab, British India to verdict. On twenty-third March 1931, the 3 courageous revolutionaries, Bhagat Ramlal Thapar and Ralli Devi. Sukhdev's father died and he was brought up by Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru have been hanged, at the same his uncle Lala Achintram.Sukhdev Thapar was a member of the Hindustan time as their bodies were secretly cremated at the banks of the River Sutlej. Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), and organised revolutionary cells in Sukhdev Thapar turned into just 24 years vintage whilst he became a martyr for Punjab and other areas of North India.Sukhdev is best remembered for his his motherland, however, he will usually be remembered for his courage, patri - involvement in the Lahore Conspiracy Case of 18 December 1928 and its after - otism, and sacrifice of his existence for India's independence. Agency. math. He was an accomplice of Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, whose conspiracy led to the assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J. P. Shivaram Hari Rajguru Saunders in 1928 in response to the vio - Shivaram Hari Rajguru was an revolutionary from Maharashtra, known mainly lent death of a veteran leader,On 23 March for his involvement in the assassination of a British Raj police officer.Rajguru 1931, the three men were hanged. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

Rrb Ntpc Top 100 Indian National Movement Questions

RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Stay Connected With SPNotifier EBooks for Bank Exams, SSC & Railways 2020 General Awareness EBooks Computer Awareness EBooks Monthly Current Affairs Capsules RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Click Here to Download the E Books for Several Exams Click here to check the topics related RRB NTPC RRB NTPC Roles and Responsibilities RRB NTPC ID Verification RRB NTPC Instructions RRB NTPC Exam Duration RRB NTPC EXSM PWD Instructions RRB NTPC Forms RRB NTPC FAQ Test Day RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS 1. The Hindu Widows Remarriage act was Explanation: Annie Besant was the first woman enacted in which of the following year? President of Indian National Congress. She presided over the 1917 Calcutta session of the A. 1865 Indian National Congress. B. 1867 C. 1856 4. In which of the following movement, all the D. 1869 top leaders of the Congress were arrested by Answer: C the British Government? Explanation: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act A. Quit India Movement was enacted on 26 July 1856 that legalised the B. Khilafat Movement remarriage of Hindu widows in all jurisdictions of C. Civil Disobedience Movement D. Home Rule Agitation India under East India Company rule. Answer: A 2. Which movement was supported by both, The Indian National Army as well as The Royal Explanation: On 8 August 1942 at the All-India Indian Navy? Congress Committee session in Bombay, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched the A. Khilafat movement 'Quit India' movement. The next day, Gandhi, B. -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

Shaheed Diwas

Shaheed Diwas drishtiias.com/printpdf/shaheed-diwas Why in News Prime Minister of India paid tributes to Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Rajguru on Shaheed Diwas (23rd March). The Day is also known as Martyrs’ Day or Sarvodaya Day. This Day should not be confused with the Martyrs’ Day observed on 30th January, the day Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated. Key Points About: Every year on 23rd March, Shaheed Diwas is observed. It was on this day that Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were executed by the British government in 1931. They were hanged to death for assassinating John Saunders, a British police officer in 1928. They had mistook him for British police superintendent James Scott. It was Scott who had ordered lathi charge, which eventually led to the death of Lala Lajpat Rai. While Singh, who had publicly announced avenging Rai’s death, went into hiding for many months after this shootout, he resurfaced along with an associate Batukeshwar Dutt, and the two, in April 1929, set off two explosive devices inside the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi. Allowed themselves to be arrested, while shouting the famous slogan: “Inquilab Zindabad“, or “Long live the revolution”. Their lives inspired countless youth and in their death, they set an example. They carved out their own path for independence, where individual heroism and their aggressive need to do something for the nation stood out, departing from the path followed by the Congress leaders then. 1/3 Bhagat Singh: Born as Bhaganwala on the 26th September, 1907, Bhagat Singh grew up in a petty-bourgeois family of Sandhu Jats settled in the Jullundur Doab district of the Punjab. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Prof. Pramod Kumar Srivastava

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prof. Pramod Kumar Srivastava Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Prof. Pramod Kumar Srivastava Renowned historian and a pioneer in the field of oral history, Prof. Pramod Kumar Srivastava was born on 7 October 1952 at Ballia, Uttar Pradesh. Prof. Srivastava received his initial education at King Edward Government Inter College, Deoria, U.P., and obtained a Master‟s degree from the Department of Western History, University of Lucknow, UP. He obtained his doctorate on „American Imperialism in Philippines‟ (1983), and D.Lit. on the „Struggle for Existence of British Colonies of South Pacific Islands, Fiji Islands, Solomon Islands, Islands of New Hebrides and Tonga‟ (1990) also from the University of Lucknow. He initially joined the Western History Department of Lucknow University as a Research Associate (1983), was appointed lecturer (1994), promoted as Professor in 2007, retired as its Head in 2015, and after retirement, became Emeritus Fellow (UGC), 2015-2017. During his distinguished teaching and research career, Prof. Pramod Kumar Srivastava headed many research projects such as „Oral History of Freedom Struggle with special reference to Ex-Andaman Freedom Fighters, 1921-1947‟ for Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi, (1991); „Segregating Dangerous Ideas: Colonial and Criminal Justice in the Andaman Islands, 1898-1948‟ as UGC Major Research Project (2006-2010); and „Political Protests from Behind the Bars: Escapes, Assaults, Work and Hunger Strikes in British Colonial Prisons‟ as UGC-Emeritus Fellow (2015-2017). He is acclaimed for documenting the role and experiences of political prisoners transported to Cellular Jail, Andaman Islands during the colonial rule. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

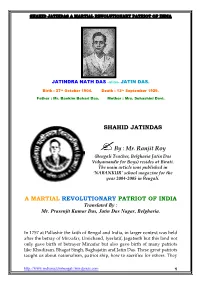

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff Meerut and the Creation of “Official” Communism in India

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East Separating the Wheat from the Chaff Meerut and the Creation of “Official” Communism in India Ali Raza ew events have been as significant for the leftist movement in colonial India as the Meerut Conspir- acy Case. At the time, the case captured the imagination of virtually all political sections in British India as well as left- leaning organizations around the globe. It also defined the way in which the FLeft viewed itself and conducted its politics. Since then, the case has continued to attract the attention of historians working on the Indian Left. Indeed, it is difficult to come across any work on the Left that does not accord a prominent place to Meerut. Despite this, the case has been viewed mostly in terms that tend to diminish its larger significance. For one, within the rather substantial body of literature devoted to the Indian Left, there have been very few works that examine the case with any degree of depth. Most of those have been authored by the Left itself or by political activists who were defendants in the case. Whether authored by the Left or by academ- ics, the literature generally contends that the Raj failed in its objective to administer a fatal blow to “com- munism” in India. Instead, it’s commonly thought that the trial actually provided a fillip to communist politics in India.1 Not only did the courtroom provide an unprecedented opportunity to the accused to openly articulate their political beliefs, but it also generated public sympathy for communism. -

History 2021

History (2-minute series) January 2021 - April 2021 Visit our website www.sleepyclasses.com or our YouTube channel for entire GS Course FREE of cost Also Available: Prelims Crash Course || Prelims Test Series T.me/SleepyClasses Table of Contents 1. Nagpur Session (1920) of the Indian National Congress ...................................1 2. 5 Important Things about Lord Curzon 1 3. The Red Fort ............................................2 4. Kalighat paintings ..................................5 5. Kangra School of Painting ....................6 6. The Rajasthani Schools of Painting ...7 7. Rogan School of Art ...............................9 8. Lala Lajpat Rai ........................................10 9. Shaheed Bhagat Singh ..........................12 10.Pathrughat Peasant Uprising ..............15 11.Gyanvapi Mosque ..................................16 12.Dr. B.R. AMBEDKAR ..............................17 13.Rabindranath Tagore ............................20 Note: The YouTube links for all the topics are embedded in the name of the Topic itself www.sleepyclasses.com Call 6280133177 T.me/SleepyClasses 1. Nagpur Session (1920) of the Indian National Congress December 1920 At the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress • The programme of non-cooperation was endorsed. • An important change was made in the Congress creed: now, instead of having the attainment of self- government through constitutional means as its goal, the Congress decided to have the attainment of Swaraj through peaceful and legitimate means, thus committing itself to an extraconstitutional mass struggle. • Some important organizational changes were made: ✓ a Congress Working Committee (CWC) of 15 members was set up to lead the Congress from now onwards; ✓ Provincial Congress Committees on linguistic basis were organized; ✓ Ward Committees was organized; and entry fee was reduced to four annas. • Gandhiji declared that if the non-cooperation programme was implemented completely, swaraj would be ushered in within a year.