(2018:11) Rasmus Broms: the Electoral Consequences Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Do Local Politicians Perceive Party Conflicts? Effects of Power, Trust and Ideology

How do local politicians perceive party conflicts? Effects of power, trust and ideology Paper prepared for presentation at NORKOM XXVI, Reykjavík 1 – 2 Dec 2017 First draft – do not cite Louise Skoog and David Karlsson School of Public Administration University of Gothenburg Abstract This study reveals how politicians’ conflict perceptions could be affected by ideology, power, and trust: socialists tend to perceive political dissent as higher while politicians who have higher levels of generalized and specified political trust perceive the level of antagonistic behaviour as lower. Influential politicians tend to perceive levels of both forms of conflict as lower. More insights about how and why political actors perceive the same situation differently could potentially foster a greater understanding – a political empathy – among political combatants that may facilitate their interactions. And in turn, increased empathy may generate a mutual political trust, which could further reduce the perception of potentially damaging conflicts such as antagonistic behaviour. The study builds on data from a survey conducted among all councillors in the 290 municipalities in Sweden. 1. Introduction Political work consists of collective processes, where politicians handle political conflicts, interact with representatives from both their own political party and from others, respond to positions and views of other actors. And how political actors perceive actions and positions of others will in turn affect their ability to cooperate (Balliet & Van Lange, 2013; De Swaan & Rapoport, 1973), develop potential strategies, and make decisions regarding future policies. In order to facilitate a functioning democracy, more knowledge is needed on how elected officials perceive the situation they are in. -

Assessment and Analytical Framework for Sustainable Urban Planning And

UPTEC STS 16001 Examensarbete 30 hp Februari 2016 Assessment and analytical framework for sustainable urban planning and development A comparative study of the city development projects in Knivsta, Norrtälje and Uppsala Wasan Hussein Abstract Assessment and analytical framework for sustainable urban planning and development Wasan Hussein Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten This thesis examines how the three urban development projects: Nydal, Norrtälje Harbor and Rosendal address the energy use in future buildings and how their energy Besöksadress: strategies are articulated in relation to requirements specified in the SGBC’s Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 certification system Citylab Action. The building Smaragden in Rosendal has been used Hus 4, Plan 0 as a model of a future building in the two other district areas in order to calculate the energy performance in each project, this by using the energy use simulation software Postadress: IDA ICE. Further on the energy mix for each district area has been analyzed in order Box 536 751 21 Uppsala to determine the renewability rate for them. The results shows that the energy performance of Rosendal was 60,8 kWh/m2/year and the heat mix was only 7,92 % Telefon: renewable. Nydal has an energy performance of 45,4 kWh/m2/year and their heat mix 018 – 471 30 03 was 76,80 % renewable. Norrtälje Harbor had the energy performance of 70,9 Telefax: kWh/m2/year and their heat mix had the renewability rate of 79,60 %. Comparing 018 – 471 30 00 these three projects, the Nydal project was the most sustainable when it came to the energy performance since it had the lowest rate. -

Monthly Journal from the Luleå Biennial 0

� Monthly journal from the Luleå Biennial 0:- Nr.1 “We Were Traitors of the Nation, They Said” Aug 2018 attack can be seen as the culmination of the preceding years of nationalism, warmongering and hatred against the communists in the re- gion. Its features and planning are remarkable: one of the key agents in the act, Ebbe Hallberg, was state attorney and chief of police in Luleå. Together with a journalist at the conservative newspaper Norrbottens-Kuriren and some army officers, they organised and carried out the bru- tal deed with the aim of silencing dissidents. We will also direct our attention to the history of the Swedish government’s establishment of internment camps for anti-fascists and anti-na- zis during the 1930s and 40s. The largest of the camps was located in the Norrbotten town Stors- ien in the Kalix municipality. Interned here were, among others, members of Flamman’s editorial staff. The camp and the attack overlap in time, 1 sentiment and the destinies they affected. 1 By addressing this dark history, we reflect on Swe- den’s idea of itself and its neutrality. How do these Monument by Toivo Lundmark, in memory of the attack events resonate today? What happens when we on Norrskensflamman. Photo: Thomas Hämén, 2018. look back and remember together? And why do these stories feel especially pertinent at this par- Between two private residences on Kungsgatan ticular time? These are questions we have raised 32 in the centre of Luleå is a memorial to the five in a research process that will lead us further to- people who fell victim to the attack on the com- wards the opening of the Luleå Biennial in Novem- munist newspaper Norrskensflamman on the 3rd ber 2018. -

Year-End Report January-December/2020 the Period in Summary

Year-end Report January-December/2020 The period in summary Full-year January-December 2020 October-December 2020 quarter • Rental income amounted to SEK 231.1m (180.6), an increase • Rental income amounted to SEK 62.8m (52.6), an increase of 28%. of 19%. • Net operating income amounted to SEK 177.4m (129.9), an • Net operating income amounted to SEK 47.2m (35.5), an increase of 37%. increase of 33%. • Income from property management1 increased 49% to SEK • Income from property management1 amounted to SEK 60.8m (40.8), of which income from property management 10.8m (13.7), of which income from property management attributable to ordinary shareholders was SEK 18.8m (4.1), attributable to ordinary shareholders was SEK 0.3m (3.2), corresponding to SEK 0.53 (0.09) per ordinary share. corresponding to SEK 0.01 (0.10) per ordinary share. • Net income after tax amounted to SEK 418.0m (571.0), • Net income after tax amounted to SEK 108.2m (150.6), corresponding to SEK 10.69 (11.77) per ordinary share. The corresponding to SEK 2.47 (4.56) per ordinary share. decrease is a result of lower value changes during the period compared with 2019. • Long-term net asset value attributable to ordinary shareholders increased 62% to SEK 2,364.6m (1,457.0), corresponding to SEK 59.75 (47.43) per ordinary share. • The Board proposes that a dividend of SEK 10.50 (10.50) per preference share be distributed quarterly and that no dividend be paid on ordinary shares. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020 We challenge conventional packaging for a sustainable future 2020 in brief External trends Strategy Target fulfi lment Our business Sustainability Directors’ report Risk management Financial reports Sustainability data Additional information We have clickable navigation. Contents This is BillerudKorsnäs 3 2020 in brief 4 CEO’s statement 6 Our business model 8 Climate effect 9 External trends 10 Strategy 12 Targets and target fulfi lment 15 BillerudKorsnäs’ mission to challenge conven- Our business 16 tional packaging for a sustainable future clearly Commercial 17 sets out why we exist and how we view our role Product area Board 18 in society. Challenging the conventional and Product area Paper 20 thinking outside the box are essential if we Innovative packaging solutions 22 are to develop the innovative and sustainable Operations 23 packaging solutions our planet needs, hand Wood supply 25 in hand with our customers and partners. Sustainability 26 Focus areas 27 Safety fi rst 28 Climate impact 30 Materials for the future 32 Our value chain 33 Sustainability foundation 34 Sustainable wood supply 34 Responsible supply chain 35 Engaging workplaces 37 Resource-effi cient production 39 Community engagement 40 Responsible business 41 Directors’ report This year’s Annual Report and Sustainability Report BillerudKorsnäs reports the Group’s fi nancial and non-fi nancial infor- Financial statements and notes mation in a joint report. The report refl ects BillerudKorsnäs’ mission Contents 43 and integrates fi nancial, sustainability and corporate governance Sustainability data 114 information to provide a full and cohesive description. BillerudKorsnäs’ statutory annual report, which includes the Directors’ report and fi nan- Additional information cial statements, can be found on pages 43–110. -

Analysis of P2g/P2l Systems in Piteå/Norrbotten for Combined Production of Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels

REPORT f3 2016:10 ANALYSIS OF P2G/P2L SYSTEMS IN PITEÅ/NORRBOTTEN FOR COMBINED PRODUCTION OF LIQUID AND GASEOUS BIOFUELS Report from an f3 project October 2016 Photo: SP/ETC Piteå. Authors: Anna-Karin Jannasch, Roger Molinder, Magnus Marklund & Sven Hermansson, SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden ANALYSIS OF P2G / P2L SYSTEMS IN PITEÅ/NORRBOTTEN FOR COMBINED PRODUCTION OF LIQUID AND GASEOUS BIOFUELS PREFACE This report is the result of a collaborative project within the Swedish Knowledge Centre for Renewable Transportation Fuels (f3). f3 is a networking organization, which focuses on development of environmentally, economically and socially sustainable renewable fuels, and Provides a broad, scientifically based and trustworthy source of knowledge for industry, governments and public authorities, Carries through system oriented research related to the entire renewable fuels value chain, Acts as national platform stimulating interaction nationally and internationally. f3 partners include Sweden’s most active universities and research institutes within the field, as well as a broad range of industry companies with high relevance. f3 has no political agenda and does not conduct lobbying activities for specific fuels or systems, nor for the f3 partners’ respective areas of interest. The f3 centre is financed jointly by the centre partners, the Swedish Energy Agency and the region of Västra Götaland. f3 also receives funding from Vinnova (Sweden’s innovation agency) as a Swedish advocacy platform towards Horizon 2020. Chalmers Industriteknik (CIT) functions as the host of the f3 organization (see www.f3centre.se). This report shoud be cited as: Jannasch, A-K, Molinder, R, Marklund, M & Hermansson, S (2016) Analysis of P2G / P2L systems in Piteå/Norrbotten for combined production of liquid and gaseous biofuels, Report No 2016:10, f3 The Swedish Knowledge Centre for Renewable Transportation Fuels, Sweden. -

Government Communication 2011/12:56 a Coordinated Long-Term Strategy for Roma Skr

Government communication 2011/12:56 A coordinated long-term strategy for Roma Skr. inclusion 2012–2032 2011/12:56 The Government hereby submits this communication to the Riksdag. Stockholm, 16 February 2012 Fredrik Reinfeldt Erik Ullenhag (Ministry of Employment) Key contents of the communication This communication presents a coordinated and long-term strategy for Roma inclusion for the period 2012–2032. The strategy includes investment in development work from 2012–2015, particularly in the areas of education and employment, for which the Government has earmarked funding (Govt. Bill. 2011/12:1, Report 2011/12:KU1, Riksdag Communication 2011/12:62). The twenty-year strategy forms part of the minority policy strategy (prop. 2008/09:158) and is to be regarded as a strengthening of this minority policy (Govt. Bill 1998/99:143). The target group is above all those Roma who are living in social and economic exclusion and are subjected to discrimination. The whole implementation of the strategy should be characterised by Roma participation and Roma influence, focusing on enhancing and continuously monitoring Roma access to human rights at the local, regional and national level. The overall goal of the twenty-year strategy is for a Roma who turns 20 years old in 2032 to have the same opportunities in life as a non-Roma. The rights of Roma who are then twenty should be safeguarded within regular structures and areas of activity to the same extent as are the rights for twenty-year-olds in the rest of the population. This communication broadly follows proposals from the Delegation for Roma Issues in its report ‘Roma rights — a strategy for Roma in Sweden’ (SOU 2010:55), and is therefore also based on various rights laid down in international agreements on human rights, i.e. -

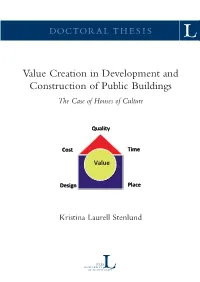

Value Creation in Development and Construction of Public Buildings

ISSN: 1402-1544 ISBN 978-91-7439-XXX-X Se i listan och fyll i siffror där kryssen är DOCTORAL T H E SI S Kristina Laurell Stenlund Department of Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering Division of Architecture and Infrastructure Value Creation in Development and ISSN: 1402-1544 ISBN 978-91-7439-129-9 Construction of Public Buildings Luleå University of Technology 2010 Creation and in ConstructionDevelopment of Value Public Buildings The Case of Houses of Culture Quality Cost Time Value Design Place Kristina Laurell Stenlund The Case of Houses of Culture VALUE CREATION IN DEVELOPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS THE CASE OF HOUSES OF CULTURE Kristina Laurell Stenlund Division of Architecture and Infrastructure Department of Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering Luleå University of Technology 971 87 LULEÅ www.ltu.se/shb VALUE CREATION IN DEVELOPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC BUILDINGS – THE CASE OF HOUSES OF CULTURE © Kristina Laurell Stenlund, 2010 Published and distributed by Luleå University of Technology 971 87 Luleå, Sweden ISSN: 1402-1544 ISBN: 978-91-7439-129-9 Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå, 2010 Preface Public buildings such as houses of culture, with a content of cultural activities, create places for people to meet, develop knowledge and understanding. This is a story of building houses of culture and the effects for the built environment in terms of social and economic effects for public clients, construction professionals, citizens and society. Open spaces such as a square or a market place enhance the expression of the city and its buildings. A fountain in the middle attracts people towards the open space creating a meeting spot with an air of experiences. -

The Swedish Water Sector

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lundin, Erik Working Paper Strategic interaction vs. regulatory compliance among regulated utilities: The Swedish water sector IFN Working Paper, No. 998 Provided in Cooperation with: Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm Suggested Citation: Lundin, Erik (2013) : Strategic interaction vs. regulatory compliance among regulated utilities: The Swedish water sector, IFN Working Paper, No. 998, Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/95638 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IFN Working Paper No. 998, 2013 Strategic Interaction vs. Regulatory Compliance among Regulated Utilities: The Swedish Water Sector Erik Lundin Research Institute of Industrial Economics P.O. -

Gørill Nilsen the USE of MARINE MAMMAL BLUBBER: PARAMETERS for DEFINING FAT-RENDERING STRUCTURES

Fennoscandia archaeologica XXXIII (2016) Gørill Nilsen THE USE OF MARINE MAMMAL BLUBBER: PARAMETERS FOR DEFINING FAT-RENDERING STRUCTURES Abstract A large number of structures, primarily pits, dating to the Bronze Age / Early Metal Period and Iron Age are situated along the coasts of Sweden, Finland, Åland Islands and Norway. The article discusses a series of examples of such structures thought to be genuine fat-rendering structures located in the Counties of Troms and Finnmark (northern Norway), the Åland Islands (Finland), and Västerbotten (Sweden), and compares them to contemporary pits from Sweden and Finland, the interpretation of which is less certain. Results from archaeological excavations and experimental reconstructions of north Norwegian slab-lined pits form the basis for discussing the interpreta- tions given to the structures in question. Keywords: Marine mammal blubber, fat-rendering, Bronze Age/Early Metal Age–Iron Age, northern Scandinavia Gørill Nilsen, Department of Archaeology and Social Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway. P.O. Box 6050 Langnes, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway: [email protected]. INTRODUCTION perature refining procedure of seal blubber has not been directly documented in Scandinavia, Throughout prehistory the utilization of marine there have been studies discussing the possibility resources such as mammals, fish, shells and of the same procedure being employed based on crustaceans is likely to have been of the utmost use-wear studies of 12000-year-old Hensbacka importance in coastal areas, both as a source of awl bits and flake axes (Schmitt 1998; Schmitt food and of raw materials. This article focuses et al. -

If a Dam Breaks

If a dam breaks Information to all residents in Boden Municipality What do you do if a dam breaks? The risk of a dam breaking on the Lule River is very small, but cannot be ignored. We in Luleå and Boden municipalities have therefore produced this folder to- gether with the County Administrative Board and the power company Vattenfall. How do you find out about a evacuate from housing for the elderly, breaking dam? so ordinary public transport will stop. In Boden town, the outdoor signal Vik- tigt meddelande (important message) is Where should you go? sounded for two minutes. Residents in Boden are to evacuate In the Harads area, information is to Kalix Municipality and will there given by personnel from the rescue receive further information. You will services and repeated messages on the possibly spend the night in Kalix, radio. Överkalix, Pajala, Övertorneå or Hap- aranda. Finland may also be a possibi- When you hear the outdoor signal turn lity for some people. on the radio, channel P4. If a dam has broken, you are informed of what has Boden residents are housed, fed and happened and what you are to do. supplied for a few days. The receiving municipality registers all evacuees. Missing persons are reported What should you do? to the police on tel. 114 14. If an evacuation is announced, you must immediately travel east to Ka- Naturally, if you have relatives or lix. See the next page for evacuation friends not affected by the dam break routes. in the Lule River Valley, you may Each person is responsible for his or travel to them. -

Annual Report 2019 Wallenstam AB

Contents This is This is Wallenstam 1 Strategic Direction Wallenstam This is how we create value 2 Business plan 2019–2023 4 Guiding principle Customer 6 Guiding principle Employee 7 Guiding principle Environment 8 Comments by the CEO 9 Vision Comments by the Chairman 12 Wallenstam shall be the natural choice of Board of Directors 14 people and companies for housing and Group Management 16 premises. The Wallenstam share 18 Investing in Wallenstam 22 Financial strategy 24 Business concept Responsible enterprise 27 We develop and manage people’s homes Risks that generate opportunities 34 and workplaces based on a high level of service and long-term sustainability in Operations and Markets selected metropolitan areas. Organization and employees 40 Market outlook 43 Property management 48 Goal Value of the properties 53 To achieve an increase in net asset value Value-creating construction 56 of SEK 40 per share through 2023. We are building here 62 Five-year summary 64 Core values Financial Reports Progress, respect, commitment. How to read our income statement 66 Administration report 67 Consolidated accounts 72 Group accounting principles and notes 76 Parent company accounts 112 Parent company accounting principles and notes 116 Auditor’s report 129 Corporate governance report 132 Property List Stockholm Business Area 138 Gothenburg Business Area 140 Completed new construction, acquisitions and sales 145 Wind power 145 Other Wallenstam’s GRI reporting 146 Annual General Meeting 2020 149 Glossary 149 Definitions see cover Calendar see cover Wallenstam’s statutory sustainability report is found on the following pages: business model pages 2–4, environmental questions pages 8, 27–33, 39 and 146–148, social conditions and personnel-related ques- tions pages 7, 27–35, 40–42 and 146–148, respect for human rights pages 27–33 and 147–148, anti-corruption pages 27–30, 32–33, 36 and 148 as well as diversity in the Board pages 42 and 133.