The Decemberists's the Tain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot |

1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com EMAIL/USERNAME PASS (FORGOT?) Email Password NEW USER? LOGIN MUSIC DEC 02, 2009, 06:07AM Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot Matt Poland [/authors/Matt%20Poland] Straight from the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina. The following audio was included in this article: The following audio was included in this article: A few years after American indie folk’s middecade spike in visibility, which, with overexposed albums including Devendra Banhart’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Joanna Newsom’s Ys, may not have been a musical zenith, the http://www.splicetoday.com/music/live-review-the-low-anthem-and-blind-pilot 1/6 1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com genre has settled back into an unassuming position that seems to fit the music better. The “freak folk” fringe having largely faded, the nourishing, elemental influence of Americana in all its permutations continues to generate quietly exciting new music. This was evident last week at Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina, during an evening of itinerant, wornin, unbeaten songs performed by The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot. Both bands make music that is melancholy but not maudlin, that is steeped in oldtime American music but not anachronistic. The Low Anthem, a Rhode Island trio, began their set with pretty unconventional instrumentation: Ben Knox Miller playing acoustic guitar and singing, Jeffrey Prystowsky on organ, and Jocie Adams playing the crotales— sort of a small xylophone made up of discs instead of planks—with a violin bow, by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen done with a violin bow since I last saw Sigur Rós. -

Take the Road to Success

B10 Thursday, April 12, 2007 Old Gold & Black Sports Baseball: Deacs go on five-game win streak, top Costal Carolina Continued from Page B1 As in the previous day, the Deacs saidd pitching coach Greg Bauer. “But One day later, Hunter made his first all the way to third base off a throwing er- jumped on the scoreboard early, as they it’s just exciting for our guys to have Wake Forest start as the Deacs defeated ror by the Chanticleers center fielder. scored all seven of their runs in the first their leader back.” Coastal Carolina 4-3 April 11. Costal Carolina managed to score an- innings. “It’s nice to put some things three innings. Returning home The Deacs got off to a good start, scor- other run in the sixth inning, but were together and get these wins,” junior Goff again keyed Wake Forest’s of- April 10, Wake ing a run in the first inning, when fresh- unable to overtake the Deacs, giving the outfielder Ben Terry said. fensive attack with a pair of hits and a overcame an early man catcher Michael Murray’s single to Deacs a 4-3 win and moving them to “We just have to carry this momentum pair of RBIs. deficit to demolish center field drove in Linnekohl. 20-16 on the season. and keep the bats and pitching going to Senior catcher Dan Rosaia and sopho- UNC-Greensboro Wake Forest held the Chanticleers “We’ve switched up the rotation a bit get these wins.” more shortstop Dustin Hood also col- by a final score of scoreless in the first two innings of play, and moved (junior fireballer Eric) Niesen The final game in the series on April lected two hits each. -

Historic Coast Culture's Farm‐To‐Fork Chef Series

Historic Coast Culture’s Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Series Presented by the St. Johns Cultural Council Overview Food is a major part of understanding any culture or region. On Florida’s Historic Coast, the culinary scene reflects 450 years of its coastal location and diverse heritage. From the original Spanish settlers, British colonists and the Greeks and Minorcans who emigrated here, visitors can savor a fascinating array of local culinary tastes and farm‐to‐table dishes. Visitors can experience everything from fine dining and quick eats to food festivals, in‐town and farm‐tasting events and culinary classes. Vision Today, farm‐to‐table Culinary is one of Florida’s Historic Coast’s key cultural assets that offers cultural travelers even deeper experiences while they are visiting. To showcase St. Johns County’s farm‐to‐table restaurants and farms, the St. Johns Cultural Council is creating a series of Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Dinners. Each will feature a top local chef from a farm‐to‐table restaurant and a local farm(s). The Chef Series will include both “In‐Town Dinners” at unusual places and “Farm Dinners” in rural settings. These culinary events will also feature local artisans, farm‐to‐table produce, local seafood and/or meats, farm‐to‐table desserts as well as local spirits. Each event will be unique, with a theme chosen by the Chef(s) for the location. These tastings will feel like an intimate dining experience where 30‐40 guests can speak one‐on‐one with the Chef(s) as well as local artisans and farms. -

Art Or Exploitation? Hit Hard by Economy Recession Causes College to Lose Approx

From cheerleader to floor leader Peace Corps requires a ‘Watchmen’ is special character for the readers SEE BACK PAGE SEE PAGE 7 SEE PAGE 9 The twice-weekly student newspaper of the College of William and Mary — Est. 1911 VOL.98, NO.37 FRIDAY, MARCH 20, 2009 FLATHATNEWS.COM THE CENTURY PROJEct Endowment Art or exploitation? hit hard by economy Recession causes College to lose approx. $100 million By JESSICA KAHLENBERG Flat Hat Staff Writer The College of William and Mary’s endowment de- creased by 17.2 percent from $580 million to approxi- mately $480.3 million between July and December of last year. Vice President of Finance Sam Jones said the endow- ment’s declining value was caused by the current eco- nomic crisis. “What we’re experiencing is what all markets are ex- periencing. We really had no place to hide because the CAITLIN FAIRChild — THE FLAT HAT decline was so severe and so broad. It goes back to the Students observe the Century Project, a controversial photography exhibit currently on display at in the Muscarelle Museum of Art. decrease in the national and global economy because that’s where peoples’ money is invested,” Jones said. Jones said there is no way to tell how long the decline Photo show opens amid debates after being moved to the Muscarelle will continue. “It all depends on what happens with the economy,” By JULIA RIESENBERG photographed under the age of eighteen be- “If you look at the picture, the focus is on the Jones said. “A lot is being done on the national level, The Flat Hat cause I know that that’s the core of the contro- energy of the woman, and the message trying but the question is when and if that will take hold. -

2015 Year in Review

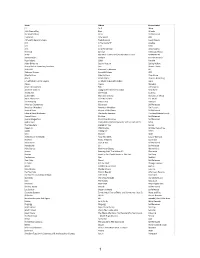

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.Com)

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.com) What was it that made it clear just a line or two into Carbon Glacier that this was something really good? It was original, first of all, both the guitar part and the melody. And it was strong, clear, very sure-footed. It was not pretentious, precious, or clever. It was recorded very well. Such were the first impressions, estimations that have only improved with time. And that wasn't even the latest album, Year of Meteors, so after a few songs, we were led there. The diversity was very satisfying, yet the continuity strong. Sounded like a young artist who really had a sense of her evolving self. There was a very free spirit to the tracking and the arrangements, a really good atmosphere. There is a palpable feeling of harmony. That was a relief, since an interview was already booked. It's still a blessed shock, every time an artist that's new to us goes into the player and a beautiful sound comes out of the speakers. And we're still very grateful when that happens. Laura Veirs is a product of the Seattle music community. She is a friend of many musical luminaries of that area, like Bill Frisell, Robin Holcomb, Wayne Horvitz, Danny Barnes, Keith Lowe and many others. She is one of the rare songwriters ever signed to Nonesuch Records. She appears to have come up through the folk channel years ago, very gracefully and convincingly into a more pop sound. This is well-illustrated by a great noisy guitar solo on "Rialto" on the new record, where the melody, handclaps and other friendly sounds keep it anchored in a very beautiful sonic bed. -

The Decemberists Explore a New Sound in MASS Moca Performance on June 15

For Immediate Release 17 January 2018 Contact: Jodi Joseph Director of Communications 413.664.4481 x8113 [email protected] The Decemberists explore a new sound in MASS MoCA performance on June 15 Acclaimed Portland band tours in support of new album, which embraces influences like Roxy Music & New Order to spark a new creative path, due March 16 NORTH ADAMS, MASSACHUSETTS — The Decemberists explore a new sound in a MASS MoCA performance on Friday, June 15 in support of their eighth studio album I’ll Be Your Girl, which will be released on March 16 on Capitol Records. The acclaimed Portland, Oregon-based band worked with producer John Congleton on the record (St. Vincent, Lana Del Rey) and embraced influences such as Roxy Music and New Order to spark a new creative path, as can be heard on the synth-driven lead single “Severed,” which is available today to stream or download. I’ll Be Your Girl will be released on a multitude of formats, including 180gm LP, 180gm Limited Edition Orange LP, 180gm Limited Edition Blue LP (available at indie record stores), 180gm Limited Edition Purple LP (available at Barnes & Noble), softpak CD, cassette, digital download, and a mystery deluxe edition box dubbed I’ll Be Your Girl: The Exploded Version, for which details will be revealed shortly. The band has also announced the first dates of their Your Girl / Your Ghost 2018 World Tour, which comes to MASS MoCA in North Adams on June 15. “When you’ve been a band for 17 years, inevitably there are habits you fall into,” says Colin Meloy. -

Music Collection

collection! 2573 songs, 6:19:50:59 total time, 9.72 GB Artist Album # Songs Total Time The Arcade Fire 2001 Demos 10 51:06 Arcade Fire EP 7 32:52 Funeral 14 1:06:04 The Arcade Fire/David Bowie Live EP 3 14:28 Audioslave Audioslave 9 39:54 Out of Exile 16 1:10:20 The Beatles A Hard Day's Night 13 30:30 Abbey Road 17 47:22 Alternate Abbey Road 7 25:44 Beatles For Sale 14 34:13 Help 15 37:30 Let It Be 10 28:15 Magical Mystery Tour 10 32:51 Past Masters - Volume One 18 42:28 Past Masters - Volume Two 13 40:02 Please Please Me 13 30:23 Revolver 13 32:19 Rubber Soul 14 35:48 Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 13 39:50 The White Album CD1 17 46:21 The White Album CD2 14 54:17 With The Beatles 14 33:24 Yellow Submarine 13 40:07 Bob Dylan Blood On The Tracks 10 51:53 Bob Dylan 14 41:07 Highway 61 Revisited 8 45:24 Love And Theft 8 36:34 Nashville 1 2:17 Shot of Love 10 44:55 The Best of Bob Dylan 6 31:31 The Essential Bob Dylan 26 1:47:02 The Freewheeling Bob Dylan 13 50:07 The Rolling Thunder Revue CD1 11 51:02 The Rolling Thunder Revue CD2 11 51:12 Bob Dylan/Johnny Cash Nashville 20 59:45 Buffalo Springfield Retrospective: The Best of Buffalo Springfield 12 40:21 The Cardigans First Band on the Moon 11 39:06 Life 14 48:07 Super Extra Gravity 14 47:57 Clap Your Hands Say Yeah Clap Your Hands Say Yeah 12 38:41 Coldplay A Rush of Blood To The Head 12 58:47 Live 2003 14 1:17:35 Live at Glastonbury 2005 15 1:17:26 Parachutes 10 35:51 X&Y 14 1:05:53 Danny Elfman Big Fish OST 22 57:39 Dave Matthews Band Before These Crowed Streets 11 1:10:21 Busted -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Knowing fans, knowing music : an exploration of fan interaction on Twitter Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0776z7tk Author McCollum, Nick Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Knowing Fans, Knowing Music: An Exploration of Fan Interaction on Twitter A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Nick McCollum Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Guy, Chair Professor David Borgo Professor Eun-Young Jung 2011 Copyright Nick McCollum, 2011 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nick McCollum is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page........................................................................................ iii Table of Contents..................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.................................................................................. v Abstract of the Thesis.............................................................................. vi Chapter I: Introduction............................................................................. 1 About Me: How I Got To This Point (in more than 140 characters)...................................................... -

RHA, Green Quad Celebrate Earth Day ‘Do It in the Dark’ Meant to Environmental Issues

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons April 2008 4-22-2008 The aiD ly Gamecock, TUESDAY, APRIL 22, 2008 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2008_apr Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, TUESDAY, APRIL 22, 2008" (2008). April. 6. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2008_apr/6 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2008 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in April by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mix Sports Nick Godwin and the Opinion..................4 Tim Roth stars in the new Puzzles....................6 Francis Ford Coppola drama Gamecocks will try to Comics.....................6 avoid a sweep against Horoscopes...............6 “Youth Without Youth.” Classifi ed............... 8 See page 7 the in-state rival Furman Paladins. See page 10 dailygamecock.com THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA TUESDAY, APRIL 22, 2008 VOL. 126, NO. 73 ● SINCE 1908 RHA, Green Quad celebrate Earth Day ‘Do It In The Dark’ meant to environmental issues. like me too and you end up “The overall goal for ‘Do It In learning stuff.” entertain, educate students on The Dark’ is to celebrate Earth Scott said the idea for serious environmental issues Day and bring awareness to the event was inspired by global warming as well as educate a conference she went to students on everyday green in November called the Haley Dreis solutions,” Scott said. Powershift 2007 in College THE DAILY GAMECOCK The event will include live music Park, Md. -

Portland's Artisan Economy

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning 1-1-2010 Brew to Bikes: Portland's Artisan Economy Charles H. Heying Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Entrepreneurial and Small Business Operations Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Heying, Charles H., "Brew to Bikes: Portland's Artisan Economy" (2010). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 52. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/52 This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Brew to bikes : Portland's artisan economy Published by Ooligan Press, Portland State University Charles H. Heying Portland State University Urban Studies Portland, Oregon This material is brought to you for free and open access by PDXScholar, Portland State University Library (http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/9027) Commitment to Sustainability Ooligan Press is committed to becoming an academic leader in sustainable publishing practices. Using both the classroom and the business, we will investigate, promote, and utilize sustainable products, technolo- gies, and practices as they relate to the production and distribution of our books. We hope to lead and encour- age the publishing community by our example. -

Decemberists Albums Free Download Torrent the Decemberists Release Music Video on Bittorrent

decemberists albums free download torrent The Decemberists Release Music Video on BitTorrent. The indie rock band “The Decemberists” has more faith in BitTorrent than MTV. The band from Portland, Oregon want their video to be available to a wide public, and BitTorrent is the easiest way to do so. For the most part, MTV and VH1 won’t touch video unless bands have sold a huge number of records, it’s impossible to get rotation.” Publishing a video on BitTorrent, is cheap, easy and efficient. The hardcore fans helped to seed the torrent and within a couple of days the torrent was downloaded more that 2000 times. Slim Moon, founder of Kill Rock Stars, the Decemberists’ record label responds: “No matter where you stand on issues of copyright, a network like BitTorrent is really for exactly this kind of thing When you have content that you want to freely distribute, it seems like … the most logical way to distribute.” The video for “Sixteen Military Wives” was shot for less than $6,000 at a high school in Portland, Oregon, and features members of the band participating in a Model United Nations, a simulation popular in high schools to teach students about problem-solving and international relations. In the video, Decemberists singer Colin Meloy represents the United States and boldly declares war on Luxembourg, a not-so-subtle jab at the Bush administration’s decision to go to war. By the way, their album “Castaways and Cutouts” probably looks familiar to most people in the BitTorrent community. The Decemberists Albums: Ranked from Worst to Best.