UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot |

1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com EMAIL/USERNAME PASS (FORGOT?) Email Password NEW USER? LOGIN MUSIC DEC 02, 2009, 06:07AM Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot Matt Poland [/authors/Matt%20Poland] Straight from the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina. The following audio was included in this article: The following audio was included in this article: A few years after American indie folk’s middecade spike in visibility, which, with overexposed albums including Devendra Banhart’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Joanna Newsom’s Ys, may not have been a musical zenith, the http://www.splicetoday.com/music/live-review-the-low-anthem-and-blind-pilot 1/6 1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com genre has settled back into an unassuming position that seems to fit the music better. The “freak folk” fringe having largely faded, the nourishing, elemental influence of Americana in all its permutations continues to generate quietly exciting new music. This was evident last week at Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina, during an evening of itinerant, wornin, unbeaten songs performed by The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot. Both bands make music that is melancholy but not maudlin, that is steeped in oldtime American music but not anachronistic. The Low Anthem, a Rhode Island trio, began their set with pretty unconventional instrumentation: Ben Knox Miller playing acoustic guitar and singing, Jeffrey Prystowsky on organ, and Jocie Adams playing the crotales— sort of a small xylophone made up of discs instead of planks—with a violin bow, by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen done with a violin bow since I last saw Sigur Rós. -

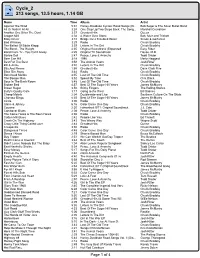

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Historic Coast Culture's Farm‐To‐Fork Chef Series

Historic Coast Culture’s Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Series Presented by the St. Johns Cultural Council Overview Food is a major part of understanding any culture or region. On Florida’s Historic Coast, the culinary scene reflects 450 years of its coastal location and diverse heritage. From the original Spanish settlers, British colonists and the Greeks and Minorcans who emigrated here, visitors can savor a fascinating array of local culinary tastes and farm‐to‐table dishes. Visitors can experience everything from fine dining and quick eats to food festivals, in‐town and farm‐tasting events and culinary classes. Vision Today, farm‐to‐table Culinary is one of Florida’s Historic Coast’s key cultural assets that offers cultural travelers even deeper experiences while they are visiting. To showcase St. Johns County’s farm‐to‐table restaurants and farms, the St. Johns Cultural Council is creating a series of Farm‐to‐Fork Chef Dinners. Each will feature a top local chef from a farm‐to‐table restaurant and a local farm(s). The Chef Series will include both “In‐Town Dinners” at unusual places and “Farm Dinners” in rural settings. These culinary events will also feature local artisans, farm‐to‐table produce, local seafood and/or meats, farm‐to‐table desserts as well as local spirits. Each event will be unique, with a theme chosen by the Chef(s) for the location. These tastings will feel like an intimate dining experience where 30‐40 guests can speak one‐on‐one with the Chef(s) as well as local artisans and farms. -

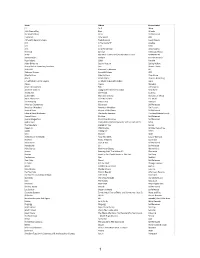

2015 Year in Review

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Spring 2013 8:00 P.M

Friday, May 17 Grant from the Southeastern Minnesota Spring 2013 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Arts Council. Carleton Symphony Band Concert This activity is made possible by the voters of Ronald Rodman, director Sunday, April 7 Minnesota through a grant from the South- 3:00 p.m. Concert Hall The Symphony Band wraps up the aca- eastern Minnesota Arts Council thanks to a Faculty Recital demic year with a concert celebrating the legislative appropriation from the arts & cultural “Exploring Organ Music: A Survey of graduating seniors. Christophe Dethier heritage fund. Manualiter Organ Music: Program III” ‘13 will be featured as clarinet soloist Lawrence Archbold, organ performing Weber’s Concertino. Other Thursday, May 30 pieces on the program include Mendels- 12:10 p.m. Concert Hall This concert is the third in a third series sohn’s Fingal’s Cave Overture, Tichelli’s Student Chamber Recital I of “Exploring Organ Music” recitals Blue Shades, Four Scottish Dances by Nicola Melville, coordinator presented by Lawrence Archbold, the Enid Malcolm Arnold, and music from the and Henry Woodward College Organist. film, The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey Friday, May 31 “A Survey of Manualiter Organ Music: by Howard Shore. 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Program III” features an all-French pro- Carleton Orchestra Concert gram with music by ten composers from Timothy Semanik, director three centuries, c.1650 to c.1950, includ- Saturday, May 18 ing Couperin, Franck, and Messiaen. 8:00 p.m. Chapel Guest Artist Concert The Carleton Orchestra’s Spring Concert will include Johannes Brahms’ Second Friday, April 19 The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Symphony as well as performances by this 8:00 p.m. -

Song/Casting: Combining Podcasts and Songs to Create a Hybrid Medium

Nate Sahr 1 Song/Casting: Combining Podcasts and Songs to Create a Hybrid Medium A Thesis Presented to the Honors Tutorial College, Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Media Arts & Studies By Nate Sahr May 2021 Nate Sahr 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction – What is a Songcast? 4 The Hypothetical Songcast: Preliminary Research & Codification 9 Storytelling in Podcasts 10 Storytelling in Songs 12 Parasocial Relationships 14 Music 16 The Actual Songcast: Creative Process 17 Evaluating my Songcast 30 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 34 Nate Sahr 3 Abstract In my creative project and associated paper, I explore a hybrid medium, songcasting, that combines the most compelling elements of podcasts with the most compelling elements of songs. For the creation of this specific songcast, I interviewed 7 talented storytellers to capture audio recordings of them telling stories. From these, I chose a story about a Minnesotan teenager and his sister exploring Australia in 1979, and I built my songcast around it. This story explores coming of age, what it means to live in the modern world, cross-cultural relations, and more. The music and narration are carefully arranged and fused together to provide an immersive listening experience. While this songcast highlights the medium’s strengths, it is only one example of the many possibilities of songcasting. By synthesizing music, an emphasis on parasocial relationships, and the storytelling modes of both songs and podcasts, songcasts stand apart as unique audio format. Nate Sahr 4 Introduction – What is a Songcast? Imagine a spectrum: on one side of the spectrum is the color blue, on the other side is the color yellow. -

The Decemberists's the Tain

November 2, 2015 American Folk Rock Cattle Raid: The Decemberists’s The Tain Kendra Leonard (Humble, TX) The Decemberists’s The Tain is a five-part, 18-minute audiovisual piece in which the music and lyrics obliquely comment on the story, crafted in stop-motion animation using paper silhouettes. In this confluence of music and literature, we hear and see an ancient Irish epic become a twentieth-century folk rock narrative. The combination of roots music with an edge and sly, knowing lyrics—together with the animation—offers an imaginative approach to the legend, the action of which is said to have taken place in the first century CE. The Decemberists’s The Tain. It’s worth the whole 18 minutes, I promise. In the original Irish legend—Táin Bó Cúailnge (pronounced “Tane bo coo-lenje”) or The Cattle Raid of Cooley—Queen Medb of Connacht plots to steal the prize bull of Ulster, the neighboring kingdom. But the bull is protected by the great Irish hero Cúchulainn, who has a number of supernatural friends who mostly help him in his quest to save the bull and, ultimately, Ulster. The battles of the Raid generally involve Cúchulainn (“coo hull-an”) against a single foe, but at times he must take on an entire army by himself, as the other warriors of Ulster are cursed and suffer a debilitating illness. The story of the Raid is one of the oldest in Irish literature and has been translated into English several times. In The Decemberists’s video, the artists include a simplified version of the story using intertitles—a technique from silent film where frames of text help viewers understand the action sequences. -

Nada Surf Til Norge – Feirer Platejubileum

Foto: Bernie DeChant 16-11-2017 16:22 CET NADA SURF TIL NORGE – FEIRER PLATEJUBILEUM NADA SURF TIL NORGE FEIRER 15-ÅRSJUBILEUMET TIL "LET GO" Nada Surf solgte ut John Dee og leverte en særdeles minneverdig aften i fjor – nå kommer de tilbake til Norge for å gjenta suksessen med en helt spesiell konsertkveld! For 15 år siden, i 2002, slapp Nada Surf albumet "Let Go", en plate som har blitt en svært viktig del av bandets historie og som anses som albumet som hjalp gruppen å sparke nytt liv i karrieren etter å ha skilt veier med Elektra Records, plateselskapet som slapp debutalbumet deres "High/Low" i 1996. Nå legger Nada Surf ut på en stor turné for å feire "Let Go" sitt 15- årsjubileum. Platen inneholder klassikere som "Inside of Love", "Blonde on Blonde", "Hi Speed Soul" og "The Way You Wear Your Head", og ble hyllet av musikkpressen. Konsertene har fått navnet "An Evening With Nada Surf", og denne spesielle kvelden vil bandet først spille "Let Go" i sin helhet, for så å spille et sett til etter en kort pause. HØR "LET GO" PÅ SPOTIFY HER Nada Surf er i dag en kvartett bestående av frontmann og gitarist Matthew Caws, bassist Daniel Lorca, trommis Ira Elliot, og Doug Gillard på gitar. Etter syv studioalbum og intensiv turnering rundt hvert slipp, bestemte Nada Surf seg for å ta en velfortjent pause etter at albumet "The Stars Are Indifferent to Astronomy" kom ut i 2012. Så, i januar 2015, når Caws informerte Nada Surf sin trofaste fanskare på Facebook om at neste album mer eller mindre var ferdiglaget, ble nyheten møtt med eksplosiv entusiasme fra fansen. -

Nada Surf High Low Vinyl

Nada surf high low vinyl Find a Nada Surf - High / Low first pressing or reissue. Complete your Nada Surf collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Musically-speaking it was the best of times and worst of times, but into this foamy, cultural hot tub came High/Low, Nada Surf's debut. The release. This month's Vinyl in the Wild takes Nada Surf's High/Low at the 50 yard line of the football field at Clairemont High School in San Diego, the. Nada Surf - High/Low - Music. of 5 stars 35 customer reviews; Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #59, in CDs & Vinyl (See Top in CDs & Vinyl). This week The Vinyl Geek is basking in the glory of the recent vinyl reissue of Nada Surf's debut album. Watch, as The Vinyl Geek unboxes his eleventh record from Vinyl Me, Please, High/Low by Nada Surf. This. Buy High / Low [ Gram Orange Vinyl Me Please Issue] (LP) by Nada Surf (LP). Amoeba Music. Ships Free in the U.S. Vinyl Me, Please takes a trip down memory lane with January's exclusive release of 'High/Low' by Nada Surf. Previously only available in the boxed set, Vinyl Me, Please are putting this out in January on g orange vinyl with an eight page. Excited to announce that 'high/low' is the Vinyl Me, Please January featured album. VMP Edition details: – g orange vinyl – 8-page book. High/Low, the debut album from Nada Surf, is getting its first stand-alone vinyl pressing through the Vinyl Me, Please service. The pressing will. -

Guy Mendilow Ensemble TFFK

FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM PERFORMED BY THE GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE COMPLETE PRESENTER’S KIT (CLIck ON A HEADING PAGE TO NAVIGATE IT) The Show …………………………………………………………………….…...…....p. 1 NOW TOURING: TALES FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM Presenters’ Testimony: Audience Impact….....…………………….……...... p. 2 Media Recognition..………..………………………….……………………….…….p. 3 Audio & Video Samples……………………….……………………………………..p. 4 About the Guy Mendilow Ensemble………………….…….………………..….p. 5 Cast Bios………………….………….………………………………….……………....p. 6 Select Performance Credits……………..……………………………………..…..p. 8 Discography, Radio, Television & Film Credits….…………………….….....p. 9 ADDITIONAL OFFERINGS University Lecture Demos…………….………….……………………………….p.10 Residences & Workshops: 13 yrs — Adult……………………………………p. 11 Residences & Workshops: Children……………….…………………………..p.11 Family Performances……………………………………………………………....p.12 Process: Springboarding from Tradition into Modern Imagination ….p. 13 Booking/Management: Guy Mendilow : Tel. +1.857-222-0235 | Fax 617-524-1463 | [email protected] www.guymendilow.com INDEX FROM THE FORGOTTEN KINGDOM PERFORMED BY THE GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE THE SHOW Embark on a musical trek to kingdoms long forgotten and bustling towns now vanished. Follow the stories of vagabond queens, pauper poets and lovers lost to the sea, all set to spellbinding arrangements of old Sephardi songs worthy of symphonic film scores. Wrap these tales up with lush soulful harmonies evoking Flamenco’s gutsiness and the longings of Fado, all combined with heart-pounding percussion, masterful narration -

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.Com)

A Conversation with Laura Veirs by Frank Goodman (12/2005, Puremusic.com) What was it that made it clear just a line or two into Carbon Glacier that this was something really good? It was original, first of all, both the guitar part and the melody. And it was strong, clear, very sure-footed. It was not pretentious, precious, or clever. It was recorded very well. Such were the first impressions, estimations that have only improved with time. And that wasn't even the latest album, Year of Meteors, so after a few songs, we were led there. The diversity was very satisfying, yet the continuity strong. Sounded like a young artist who really had a sense of her evolving self. There was a very free spirit to the tracking and the arrangements, a really good atmosphere. There is a palpable feeling of harmony. That was a relief, since an interview was already booked. It's still a blessed shock, every time an artist that's new to us goes into the player and a beautiful sound comes out of the speakers. And we're still very grateful when that happens. Laura Veirs is a product of the Seattle music community. She is a friend of many musical luminaries of that area, like Bill Frisell, Robin Holcomb, Wayne Horvitz, Danny Barnes, Keith Lowe and many others. She is one of the rare songwriters ever signed to Nonesuch Records. She appears to have come up through the folk channel years ago, very gracefully and convincingly into a more pop sound. This is well-illustrated by a great noisy guitar solo on "Rialto" on the new record, where the melody, handclaps and other friendly sounds keep it anchored in a very beautiful sonic bed. -

PRESS RELEASE July 24, 2014 Contact: Camille Cintrón, Manager, Public Relations 703.255.4096 Or [email protected]

PRESS RELEASE July 24, 2014 Contact: Camille Cintrón, Manager, Public Relations 703.255.4096 or [email protected] High-resolution images of the artists listed are available on Wolf Trap’s website: wolftrap.org/Media_and_Newsroom/Photos_for_Publication.aspx Wolf Trap Presents Noche Flamenca, Nickel Creek and Josh Ritter, Boney James and Eric Benet, YANNI, and ABBA—The Concert All Shows at the Filene Center at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, 1551 Trap Road, Vienna, Virginia 22182 Noche Flamenca Tuesday, August 12, 2014 at 8:30 pm The passionate flair of traditional Spanish dance and music strikes a pose onstage at the Filene Center with Noche Flamenca. The group, founded in Madrid in 1993, is highly decorated, having been honored with the Lucille Lortel Award for Special Theatrical Experience in 2003 and awards from the National Dance Project in 2006 and 2009. Additionally, lead dancer and co-founder Soledad Barrio won a New York Dance and Performance Award for her acclaimed style. Her husband Martín Santangelo co- founded the group with her and serves as the artistic director, stylizing shows that are performed throughout the world, including full annual seasons in Buenos Aires and New York City. Dance Magazine says Barrio is “a gift to flamenco and the troupe a testament to the art’s underlying relevance.” Video: Noche Flamenca – Promotional Video Nickel Creek Josh Ritter Wednesday, August 13, 2014 at 7:30 pm “Newgrass” band Nickel Creek partners with acoustic artist Josh Ritter to create an evening of homey folk at the Filene Center. Nickel Creek brings their unique blend of progressive bluegrass and acoustic folk to their Wolf Trap debut.