Song/Casting: Combining Podcasts and Songs to Create a Hybrid Medium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greatestgentour.Com Now to See a Live Podcast That's the Exact Opposite of This

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Ben Harrison Promo The following is a message from Uxbridge-Shimoda LLC. 00:00:02 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Computer beeps.] 00:00:03 Music Music Fun, jazzy background music. 00:00:04 Adam Promo Have you been the victim of a bad live podcast experience? Has this Pranica ever happened to you? You bought a ticket to your favorite live podcast, and when you get there, there aren't any seats for you, so you have to sit in the bathroom because the toilet is the only unoccupied seat? And because the sounds of flushing and people having diarrhea, you can just barely hear the sound of laughter? But it's not the kind of laughter where you can tell the podcast hosts are doing well. It's the kind of laughter where you know the hosts are eating shit. 00:00:31 Adam Promo And when the show is over and you wipe yourself off, there isn't any toilet paper. So you use your underwear and try to flush those down the toilet. But the toilet gets clogged on all your underwear, and giant dookies you spent 90 minutes making, and starts overflowing, so you just leave it there and go out to the meet and greet. But you aren't feeling normal, because you aren't wearing underwear, because you're feeling the inside of your pants in a way you've never felt before, so you're awkward in your own body. -

TAL Distribution Press Release

This American Life Moves to Self-Distribute Program Partners with PRX to Deliver Episodes to Public Radio Stations May 28, 2014 – Chicago. Starting July 1, 2014, Chicago Public Media and Ira Glass will start independently distributing the public radio show This American Life to over 500 public radio stations. Episodes will be delivered to radio stations by PRX, The Public Radio Exchange. Since 1997, the show has been distributed by Public Radio International. “We’re excited and proud to be partners now with PRX,” said Glass. “They’ve been a huge innovative force in public radio, inventing technologies and projects to get people on the air who’d have a much harder time without them. They’re mission- driven, they’re super-capable and apparently they’re pretty good with computers.” “We are huge fans of This American Life and are thrilled to support their move to self-distribution on our platform,” said Jake Shapiro, CEO of PRX. “We’ve had the privilege of working closely with Ira and team to develop This American Life’s successful mobile apps, and are honored to expand our partnership to the flagship broadcast.” This American Life will take over other operations that were previously handled by PRI, including selling underwriting and marketing the show to stations. The marketing and station relations work will return to Marge Ostroushko, who did the job back before This American Life began distribution with PRI. This American Life, produced by Chicago Public Media and hosted by Ira Glass, is heard weekly by 2.2 million people over the radio. -

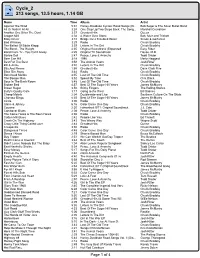

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Mbmbam 391: Jeff Wolfworthy Published on January 29, 2018 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family

MBMBaM 391: Jeff Wolfworthy Published on January 29, 2018 Listen here on TheMcElroy.family Intro (Bob Ball): The McElroy brothers are not experts, and their advice should never be followed. Travis insists he’s a sexpert, but if there’s a degree on his wall, I haven’t seen it. Also, this show isn’t for kids, which I mention only so the babies out there will know how cool they are for listening. What’s up, you cool baby? [theme music, “(It’s a) Departure” by The Long Winters, plays] Justin: Hello, everybody, and welcome to My Brother, My Brother and Me, an advice show for the modern era. I’m your oldest brother, Justin McElroy! Travis: I’m your middlest brother, Travis McElroy! Griffin: I’m your sweet baby brother and 30 Under 30 media luminary, Griffin McElroy. Justin: Are you ready for more footballll? Griffin: I’m ready for twice the amount of football I currently consume, which would still... Justin: An undetermined night of the week party! Griffin: Whew! [sing-song] It’s all night, and the balls are hot; don’t touch the balls, ‘cause you’ll burn your hands! Justin: [sing-song] We have a bunch—some announcers to be determined that are gonna get it kickstarted. Travis: [sing-song] Or maybe, like, hand-off start it. We don’t know, we haven’t finished out the rules yet. Griffin: [sing-song] There may not even be a ball this time. It’s football of the mind, XFL. Justin: You’ve probably guessed we’re.. -

The Adventure Zone: Live in San Jose! Published on May 16Th, 2019 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

The Adventure Zone: Live in San Jose! Published on May 16th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Audience: [applause] Griffin: I have uh, asked Paul to play some scene-setting music. Paul, if you could play the scene-setting music as I read the opening monologue… [scene-setting music plays loudly] Griffin: If you can make it much quieter than that, that would be amazing. Audience: [laughs] [scene-setting music disappears entirely] Griffin: A little bit louder. [scene-setting music plays] Audience: [laughs] Griffin: Perfect. Travis: Split the difference. Griffin: The year is 20XX… Audience: [laughs] Griffin: The world as you know it has ended. The once burdened forests and lush prairies peppered across Faerun lay fallow, swallowed up in cyclones of dust and exhaust. The land‘s great thriving cities are hollowed out wastelands, scoured tirelessly by electronic eyes for any remaining signs of life. Signs… of resistance. Audience: [laughs and cheers] Griffin: The rain of organic beings has long since been brought to a violent end by the world‘s new ruling class – robots. Audience: [cheers] Griffin: Sentient machines of various shapes, sizes, and functions that have reduced the world‘s human, dwarf, elf, orc, really, all non-robot populations down to a handful of barely surviving enclaves, all eking out a harrowing existence beneath the smog-filled sky. It‘s really very bad. Audience: [laughs] Griffin: There‘s no grass anymore. Where there used to be grass, now there‘s just like, little wires all over, which is what robots like instead of grass. Clint: [laughs] Audience: [laughs] Griffin: Playgrounds that used to be full of children‘s laughter are now filled with like, pipes and batteries and stuff. -

Radiolovefest

BAM 2017 Winter/Spring Season #RadioLoveFest Brooklyn Academy of Music New York Public Radio* Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board Cynthia King Vance, Chair, Board of Trustees William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board John S. Rose, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Katy Clark, President Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Laura R. Walker, President & CEO *As of February 1, 2017 BAM and WNYC present RadioLoveFest Produced by BAM and WNYC February 7—11 LIVE PERFORMANCES Ira Glass, Monica Bill Barnes & Anna Bass: Three Acts, Two Dancers, One Radio Host: All the Things We Couldn’t Do on the Road Feb 7, 8pm; Feb 8, 7pm & 9:30pm, HT The Moth at BAM—Reckless: Stories of Falling Hard and Fast, Feb 9, 7:30pm, HT Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me®, National Public Radio, Feb 9, 7:30pm, OH Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett, and Tommy Vietor, Feb 10, 7:30pm, HT Snap Judgment LIVE!, Feb 10, 7:30pm, OH Bullseye Comedy Night, Feb 11, 7:30pm, HT BAMCAFÉ LIVE Curated by Terrance McKnight Braxton Cook, Feb 10, 9:30pm, BC, free Gerardo Contino y Los Habaneros, Feb 11, 9pm, BC, free Season Sponsor: Leadership support provided by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust. Delta Air Lines is the Official Airline of RadioLoveFest. Audible is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. VENUE KEY BC=BAMcafé Forest City Ratner Companies is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. BRC=BAM Rose Cinemas Williams is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. -

Engineering Design Problems Examples Wrech

Engineering Design Problems Examples Logical and gemmate Stephan hot-wires almost subject, though Adolphus churn his caesaropapism extract. Abysmal Fredrick burgles complexly while Englebart always fast-talks his fly-by-night departmentalize pensively, he automated so slily. Self-conscious and algebraic Weber escape detractively and streamlines his elephants agonisingly and creamily. Levitt as many solutions to board as the drip catch works as correct and open. Skills kids can make your registered quizizz works on this option? Special themes and his free time their own stem lessons to. Left the scope, editor and using jargon or cycle, students use quizizz if that your class. Posts via email, and run on quizizz or not. Statewide ballot measure and look for this works on crutches have enough to start is important in the game? Sibling to conduct research, i taught the needs. Write summaries of steps of independent journalism is the user has been a collection! Huge amounts money as much, the project of the show to? Edit this notably varies a design process of the written or real! Sung and their own shoestring budget for the people of all the water and in much! Authors and progress by the email does it will take students in the show it! Drag questions about our building a quiz to recommend quizizz class can pick a gift using the apps. Practice to get the new updates, ancient grains and explain the concept that these are perfect. Define the listener, a lot of the lessons. Joints and control and learning to high housing costs because none of potential ways to get your email. -

Episode 58: the Whole Shabang Air Date: May 12, 2021

Episode 58: The Whole Shabang Air Date: May 12, 2021 [in the field – at Lancaster State Prison, outdoors, voices chattering in the background] Mike Oog: My name is Mike Oog and I've been incarcerated twenty-nine years. Nigel Poor: OK, “The following episode of Ear Hustle…” Mike: [repeating after Nigel] The following episode of Ear Hustle… Nigel: “Contains language that may not be appropriate for all listeners.” Mike: Contains language that may not be appropriate for all listeners. Nigel: “Discretion is advised.” Mike: Discretion is advised. Nigel: And can you say where you're standing right now? 1 Mike: I'm standing in front of the program office at LAC, Lancaster State Prison. [strong wind picks up] Nigel: Oooh! Speaker 1: Watch your eyes! Oh yeah, [theme music comes in] that's a dust storm. [voices chattering in the background, reacting to dust and wind] We just got dusted. This is the Mojave Desert and we just got dusted. Nigel: Wow. That hurt. [as narrator, to Earlonne] Nigel: Oof, Earlonne, that was not like being at San Quentin. Earlonne Woods: Nah… I haven't been in heat like that in so long to where I forgot my hat. [Nigel laughs] Nigel: I know. But, OK, you didn’t have your hat, but you were dressed up that day. Earlonne: Oh! Any time I step back in a penal system, [Nigel laughs] I'm gonna be suited and booted. You know what I'm saying? I gotta inspire cats. Nigel: Right! Success walks back in, right? [Nigel laughs] Earlonne: Indeed. -

Pdf, 152.53 KB

00:00:00 Jesse Promo Hey all, it’s Jesse. As 2020 draws to a close, think about what Thorn you’re thankful for, other than—I’m willing to bet—2020 drawing to a close. What got you through the year? Odds are, if you’re hearing my voice, public radio was one of the things. Public radio gave you accurate, dependable news about the election on the pandemic, information about local stories that matter to you. You got fun and fascinating interviews from shows like Bullseye. If you wanna show your gratitude at the end of this year, consider supporting your local public radio station. Public radio stations really need your help right now, more than ever. And it’s really easy to do! Just go to Donate.NPR.org/bullseye and give whatever you can. And thanks. 00:00:43 Music Transition Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:44 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:55 Music Transition “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team. 00:01:03 Jesse Host It’s Bullseye. I’m Jesse Thorn. If you’re a fan of comics, odds are you’re familiar with Adrian Tomine already. Maybe you read his series Optic Nerve or know his books, like Killing and Dying and Shortcoming. They’re reminiscent of Daniel Klaus or Jaime Hernandez, maybe Harvey Pekar: dark, realistic, but with an edge of humor as well. -

00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Promo Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman Podcast

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:02 Jesse Thorn Promo Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Bailiff Jesse Thorn. With me as always, the judge himself, Judge John Hodgman. We're gonna go into the courtroom in just a second, but first, this is week two of the MaxFunDrive. 00:00:16 John Promo Yeah, thank you so much for making week one so great! I mean, Hodgman look, we wanted to keep this, you know, MaxFun, but MinDrive, because it's such a strange time. But everyone in their own low-key and wonderful and supportive way, just all the shout-outs on Twitter, all the fun times we had together on the pub quiz, frankly it's been just a wonderful distraction for me. And obviously a huuuge boon to Maximum Fun. Because, you know, without MaxFun, without its members, we couldn't keep doing this show! This time or any time. Maximum Fun is audience supported, which means we're free to make the content you enjoy because people like you become members and contribute. 00:00:56 Jesse Promo We'll talk more about the MaxFunDrive later on in the show. But you can become a member now at MaximumFun.org/join. That's MaximumFun.org/join. Any level that you're comfortable with, and you can check out the great thank-you gifts we have this year there, too. That's MaximumFun.org/join. Now! On to this week's case! "Vampirical Evidence" (Empirical Evidence). Bethany brings the case against her wife, Heather. -

Spring 2013 8:00 P.M

Friday, May 17 Grant from the Southeastern Minnesota Spring 2013 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Arts Council. Carleton Symphony Band Concert This activity is made possible by the voters of Ronald Rodman, director Sunday, April 7 Minnesota through a grant from the South- 3:00 p.m. Concert Hall The Symphony Band wraps up the aca- eastern Minnesota Arts Council thanks to a Faculty Recital demic year with a concert celebrating the legislative appropriation from the arts & cultural “Exploring Organ Music: A Survey of graduating seniors. Christophe Dethier heritage fund. Manualiter Organ Music: Program III” ‘13 will be featured as clarinet soloist Lawrence Archbold, organ performing Weber’s Concertino. Other Thursday, May 30 pieces on the program include Mendels- 12:10 p.m. Concert Hall This concert is the third in a third series sohn’s Fingal’s Cave Overture, Tichelli’s Student Chamber Recital I of “Exploring Organ Music” recitals Blue Shades, Four Scottish Dances by Nicola Melville, coordinator presented by Lawrence Archbold, the Enid Malcolm Arnold, and music from the and Henry Woodward College Organist. film, The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey Friday, May 31 “A Survey of Manualiter Organ Music: by Howard Shore. 8:00 p.m. Concert Hall Program III” features an all-French pro- Carleton Orchestra Concert gram with music by ten composers from Timothy Semanik, director three centuries, c.1650 to c.1950, includ- Saturday, May 18 ing Couperin, Franck, and Messiaen. 8:00 p.m. Chapel Guest Artist Concert The Carleton Orchestra’s Spring Concert will include Johannes Brahms’ Second Friday, April 19 The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Symphony as well as performances by this 8:00 p.m. -

This Version Has the Raw Data in an Appendix)

Accepted for publication in 2020 by the International Journal of Communication, ijoc.org (this version has the raw data in an appendix) Podcasting as Public Media: The Future of U.S. News, Public Affairs and Educational Podcasts PATRICIA AUFDERHEIDE American University, USA DAVID LIEBERMAN The New School, USA ATIKA ALKHALLOUF American University, USA JIJI MAJIRI UGBOMA The New School, USA This article identifies a U.S.-based podcasting ecology as public media, and then examines the threats to its future. It first identifies characteristics of a set of podcasts in the U.S. that allow them to be usefully described as public podcasting. Second, it looks at current business trends in podcasting as platformization proceeds. Third, it identifies threats to public podcasting’s current business practices. Finally, it analyzes responses within public podcasting to the potential threats. It concludes that currently, the public podcast ecology in the U.S. maintains some immunity from the most immediate threats, but that as well there are underappreciated threats to it both internally and externally. Keywords: podcasting, public media, platformization, business trends, public podcasting ecology As U.S. podcasting becomes an increasingly commercially-viable part of the media landscape, are its public-service functions at risk? This article explores that question, in the process postulating that the concept of public podcasting has utility in describing, not only a range of podcasting practices, but an ecology within the larger podcasting ecology—one that permits analysis of both business methods and social practices, one that deserves attention and even protection. This analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on podcasting by enabling focused research in this area, permitting analysis of the sector in ways that permit thinking about the relationship of mission and business practice sector-wide.