Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photographic Evidence of Desert Cat Felis Silvestris Ornata and Caracal

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Photographic evidence of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated forests of Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, India Raju Lal Gurjar* & Anil Kumar Chhangani Department of Environmental Science, Maharaja Ganga Singh University, Bikaner- 334001 (Rajasthan) *Email: [email protected] Received: July 04, 2018 Accepted: August 22, 2018 ABSTRACT We recorded movement of Desert cat Felis silvestris ornata and Caracal Felis caracal using camera traps in human dominated corridors from Ranthambhore National Park to Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary, Western India. We obtained 9 caracal captures and one Desert cat capture in 360 camera trap nights. Our findings revels that presence of both cat species outside park in corridors was associated with functionality of corridor as well as availability of prey. Further the forest patches, ravines and undulating terrain supports dispersal of small mammals too. Desert cat and Caracals were more active late at night and during crepuscular hours. There was a difference in their activity between dusk and dawn. Since this is its kind of observation beyond parks regime we genuinely argue for conservation of corridors and its protection leads us to conserve both large as well as small cats in the region. Keywords: Desert Cat, Caracal, Camera Trap, Ranthambhore National Park, Kailadevi Wildlife Sanctuary INTRODUCTION India has 11 species of small cats besides the charismatic big cats like tiger Panthera tigris, leopard Panthera pardus, Snow leopard Panthera uncia and Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica. -

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

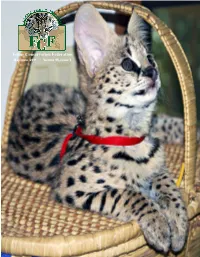

Feline Conservation Federation May/June 2011 • Volume 55, Issue 3 T ABLE Ofcontents Features MAY/JUNE 2011 | VOLUME 55, ISSUE 3

Feline Conservation Federation May/June 2011 • Volume 55, Issue 3 T ABLE OFcontents Features MAY/JUNE 2011 | VOLUME 55, ISSUE 3 Great Art for a Great Cause 15 Ocelot cub portrait by Jessica Kale to go to the highest bidder. 17 Make Fundraising Music with the FCF Let J.W. Everitt make your next event sing! 21 Initial Steps Toward Bigger & Greater Dreams Wildlife educators course and top-level exhibitors help prepare Craig DeRosa for his future. Stewie the Serval: Supercat! 25 Jackie Adebahr introduces us to a beloved member of her family. 30 Small Cat Populations Decimated in the Kẻ Gỗ-Khê Nét Lowlands, Central Vietnam Daniel Wilson finds no cats in the forest. Paws for More Outstanding Art at 32 Convention Cindy Weitzel makes a philanthropic gift to the FCF. Can I really buy a Cheetah on the Internet?! 35 Internet investigator Dolly Gluck wants answers. Small Cat Awareness in Massachusetts 45 Mona Headen attends show featuring Jim Sanderson, Debi Willoughby and Geoffroy’s cat Spirit. 25 Cover Photo: Gucci lays in wait for the Easter bunny. Photo by Rebecca Jensen, owner, A Wild Side Cattery. 15 16 45 Feline Conservation Federation Volume 55, Issue 3 • May/June 2011 TO SUBSCRIBE TO THE FCF JOURNAL AND JOINTHE FCF IN ITS CONSERVATION EFFORTS A membership to the FCF entitles you to six issues of the Journal, the back-issue DVD, an invitation to FCF hus- bandry and wildlife education courses and annual convention, and participation in our online discussion group. The FCF works to improve captive feline husbandry and ensure that habitat is available. -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

First Photographic Record of Asiatic Wildcat in Bandhav- Garh TR, India

short communication TAHIR ALI RATHER1*, SHARAD KUMAR2, SHAIZAH TAJDAR1, RAMAN KALIKA SRIVASTAVA3 AND JAMAL A. KHAN1 First photographic record of Asiatic wildcat in Bandhav- garh TR, India The Asiatic wildcat Felis silvestris ornata is one of five subspecies of the wildcat Felis silvestris listed as Least Concern in the IUCN Red list. Being previously un- reported in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve TR, we provide here the first photographic evidences of Asiatic wildcat in Bandhavgarh TR from a camera trap survey. During subsequent camera trapping, we recorded kittens of Asiatic wildcat, strongly sugge- sting the existence of a breeding population in Bandhavgarh TR. We report a first photographic record of Asi- (Fig. 3) on 6 May 2016 at a site located at atic wildcat in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, 23°49'6.7" N / 80°56'11.7" E at an eleva- Madhya Pradesh, India (Fig. 1). The Asiatic tion of 411 m. During the study period of six Fig. 1. Map of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve wildcat is considered as one of five subspe- months we recorded the Asiatic wildcat on and camera trap locations of Asiatic wild- cies of the wildcat Felis silvestris which is 15 occasions at different camera trap sta- cat (TCF, Bandhavgarh). listed as Least Concern in the IUCN Red List tions in habitats ranging from well wooded (Yamaguchi et al. 2015). The Asiatic wildcat Sal forests, mixed forests to scrubs and is legally protected in India under Schedule around human habitations. Information on I of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972). The their status, range, distribution and ecology Asiatic wildcat occurs in a wide variety of are lacking in India and most of the informa- habitats ranging from arid, semi-arid, scrubs, tion comes from opportunistic sightings. -

Predicting Global Population Connectivity and Targeting Conservation Action for Snow Leopard Across Its Range

Ecography 39: 419–426, 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecog.01691 © 2015 e Authors. Ecography © 2015 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Bethany Bradley. Editor-in-Chief: Miguel Araújo. Accepted 27 April 2015 Predicting global population connectivity and targeting conservation action for snow leopard across its range Philip Riordan, Samuel A. Cushman, David Mallon, Kun Shi and Joelene Hughes P. Riordan ([email protected]) and J. Hughes, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. – S. A. Cushman, US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 800 E Beckwith, Missoula, MT 59801, USA. – D. Mallon, Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, School of Science and the Environment, Manchester Metropolitan Univ., Manchester, M1 5GD, UK. – K. Shi and PR, Wildlife Inst., College of Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry Univ., 35, Tsinghua-East Road, Beijing 100083, China. Movements of individuals within and among populations help to maintain genetic variability and population viability. erefore, understanding landscape connectivity is vital for effective species conservation. e snow leopard is endemic to mountainous areas of central Asia and occurs within 12 countries. We assess potential connectivity across the species’ range to highlight corridors for dispersal and genetic flow between populations, prioritizing research and conservation action for this wide-ranging, endangered top-predator. We used resistant kernel modeling to assess snow leopard population connectivity across its global range. We developed an expert-based resistance surface that predicted cost of movement as functions of topographical complexity and land cover. e distribution of individuals was simulated as a uniform density of points throughout the currently accepted global range. -

Selected Methods of in Vitro Embryo Production in Felids – a Review*

Animal Science Papers and Reports vol. 35 (2017) no. 4, 361-377 Institute of Genetics and Animal Breeding, Jastrzębiec, Poland Selected methods of in vitro embryo production in felids – a review* Sylwia Prochowska1**, Wojciech Niżański1, Agnieszka Partyka1, Joanna Kochan2, Wiesława Młodawska2, Agnieszka Nowak2, Anna Migdał2, Józef Skotnicki3, Teresa Grega3, Marcin Pałys3 1 Department of Reproduction and Clinic of Farm Animals, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, pl. Grunwaldzki 49, 50-366 Wrocław 2 Institute of Veterinary Science, University of Agriculture in Cracow, Al. Mickiewicza 24/28, 30-059 Kraków 3 Foundation Municipal Park and the Zoological Garden in Cracow, Kasy Oszczędności Miasta Krakowa 14, 30-232 Kraków (Accepted November 6, 2017) During the past decade the need for Artificial Reproductive Techniques in felids has greatly increased. Mostly, this is a result of growing expectations that these techniques may be applied in conservation biology and thereby contribute to saving wild felids from extinction. In this article we describe three most common methods of obtaining embryos in vitro in the domestic cat and its wild relatives: classic in vitro fertilisation, in vitro fertilisation by intracytoplasmic sperm injection and somatic cell nuclear transfer. Each of the methods provides a cleavage rate of around 50% and approx. 20% of embryos develop to the blastocyst stage. After the transfer of embryos produced by these methods, scientists obtained living offspring of the domestic cat, as well as several wild cats: the tiger, serval, fishing cat, caracal, ocelot, wild cat, sand cat, black-footed cat and the oncilla. These successes, in spite of the low efficiency of the discussed methods, are promising and suggest that biotechniques of reproduction will be valuable tools in the protection of wild species. -

Return of a Lost Structure in the Evolution of Felid Dentition Revisited: a Devoevo Perspective on the Irreversibility of Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Return of a lost structure in the evolution of felid dentition revisited: A DevoEvo perspective on the irreversibility of evolution Vincent J. Lynch Department of Biological Sciences, University at Buffalo, SUNY, 551 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Correspondence: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Abstract There is a longstanding interest in whether the loss of complex characters is reversible (so-called “Dollo’s law”). Reevolution has been suggested for numerous traits but among the first was Kurtén (1963), who proposed that the presence of the second lower molar (M2) of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) was a violation of Dollo’s law because all other Felids lack M2. While an early and often cited example for the reevolution of a complex trait, Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) used an ad hoc parsimony argument to support their proposition that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. Here I revisit the evidence that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx using explicit parsimony and maximum likelihood models of character evolution and find strong evidence that Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) were correct – M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. -

2007 Conserving the Asiatic Cheetah in Iran: Launching the First Radio- Telemetry Study

ISSN 1027-2992 CAT NEWS N° 46 Spring 2007 SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION IUCNThe World Conservation Union Cat Specialist Group Contents CAT News 1. Editorial: Cat News - Quo vadis ............................................................3 is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component of the Species 2. Cheetahs in Central Asia: A Historical Summary ..................................4 Survival Commission of The World 3. Launching the First Radio-Telemetry Study for Cheetahs in Iran ...........8 Conservation Union (IUCN). 4. 2nd OGRAN Meeting in Tamanrasset, Algeria ...................................12 It is published twice a year, 5. Range-wide Conservation Planning for Cheetah and Wild Dog..........13 and is available to subscribers to Friends of the Cat Group. 6. 2005 Amur Tiger Census .....................................................................14 7. Sighting of Asiatic Wildcat in Gogelao Enclosure, Rajasthan .............17 For a subscription please contact Christine Breitenmoser at 8. Sighting of Rusty-spotted Cat in Central Gujarat ................................18 [email protected] 9. Human Attitudes Towards Wild Felids in Southern Chile ...................19 Contributions, papers, press 10. First Study of Snow Leopards Using GPS Collars in Pakistan ................22 cuttings, etc. about wild cats 11. Binational Jaguar Population in the American Gran Chaco .....................24 are welcome. 12. A New Old Clouded Leopard ..............................................................26 Send news items to 13. Lifting China‘s Tiger Trade Ban Would Be a Catastrophe ..................28 [email protected], original contributions and short notes 14. Diet of Leopard and Caracal in Northern UAE and Oman ..................30 to [email protected]. 15. A Framework for the Conservation of the Arabian Leopard ...............32 Guidelines for authors are available 16. Photos of Persian Leopard in the Alborz Mountains, Iran ...................34 at www.catsg.org 17. -

Conservation of Snow Leopards: Spill-Over Benefits for Other Carnivores?

Conservation of snow leopards: spill-over benefits for other carnivores? J USTINE S. ALEXANDER,JEREMY J. CUSACK,CHEN P ENGJU S HI K UN and P HILIP R IORDAN Abstract In high-altitude settings of Central Asia the protection will also benefit many other species (Noss, Endangered snow leopard Panthera uncia has been recog- ; Andelman & Fagan, ). Top predators often nized as a potential umbrella species. As a first step in asses- meet this criterion (Sergio et al., ; Dalerum et al., sing the potential benefits of snow leopard conservation for ; Rozylowicz et al., ), with many large carnivores other carnivores, we sought a better understanding of the additionally possessing charismatic qualities and wide pub- presence of other carnivores in areas occupied by snow leo- lic recognition that can attract disproportionate conserva- pards in China’s Qilianshan National Nature Reserve. We tion investments (Sergio et al., ; Karanth & Chellam, used camera-trap and sign surveys to examine whether ). The flagship status of such carnivores can bring in- other carnivores were using the same travel routes as snow direct benefits to other species that are neglected or over- leopards at two spatial scales. We also considered temporal looked, by highlighting common threats and emphasizing interactions between species. Our results confirm that other their mutual dependence. A fundamental step in identifying carnivores, including the red fox Vulpes vulpes, grey wolf and quantifying potential benefits for other species is to Canis lupus, Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx and dhole Cuon alpinus, demonstrate the spatial extent of co-occurrence in the occur along snow leopard travel routes, albeit with low detec- area of interest (Andelman & Fagan, ). -

Wild Cat List by Common Name

Wild Cat Family Wild Cat List by Genus # Genus Species Common Name 1 Acinonyx Acinonyx jubatus Cheetah 2 Caracal Caracal aurata African golden cat 3 Caracal caracal Caracal 4 Catopuma Catopuma badia Bornean bay cat 5 Catopuma temminckii Asiatic golden cat 6 Felis Felis chaus Jungle cat 7 Felis margarita Sand cat 8 Felis nigripes Black-footed cat 9 Felis silvestris European wildcat 10 Felis lybica African & Asiatic wildcat 11 Felis bieti Chinese mountain cat 12 Herpailurus Herpailurus yagouaroundi Jaguarundi 13 Leopardus Leopardus geoffroyi Geoffroy’s cat 14 Leopardus guigna Guiña, Kodkod 15 Leopardus jacobita Andean cat 16 Leopardus pardalis Ocelot 17 Leopardus tigrinus Northern tiger cat 18 Leopardus guttulus Southern tiger cat 19 Leopardus colocola Pampas cat 20 Leopardus wiedii Margay 21 Leptailurus Leptailurus serval Serval 22 Lynx Lynx lynx Eurasian lynx 23 Lynx pardinus Iberian lynx 24 Lynx canadensis Canada lynx 25 Lynx rufus Bobcat 26 Neofelis Neofelis nebulosa Clouded leopard 27 Neofelis diardi Sunda clouded leopard 28 Otocolobus Otocolobus manul Pallas’s cat 29 Panthera Panthera leo Lion 30 Panthera onca Jaguar 31 Panthera pardus Leopard 32 Panthera tigris Tiger 33 Panthera uncia Snow leopard 34 Pardofelis Pardofelis marmorata Marbled cat 35 Prionailurus Prionailurus bengalensis Leopard cat 36 Prionailurus javanensis Sunda leopard cat 37 Prionailurus planiceps Flat-headed cat 38 Prionailurus rubiginosus Rusty-spotted cat 39 Prionailurus viverrinus Fishing cat 40 Puma Puma concolor Puma References: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2018-2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. 20 Nov 2018. Kitchener et al. 2017. A revised taxonomy of the Felidae. The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN / SSC Cat Specialist Group.