Management of Large Carnivores in the Alps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study

Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study 15 August 2014 Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Executive Summary The UNESCO World Heritage Committee encouraged the States Parties to harmonize their Tentative Lists of potential World Heritage Sites at the regional and thematic level. Consequently, the UNESCO World Heritage Working Group of the Alpine Convention was mandated by the Ministers to contribute to the harmo- nization of the National Tentative Lists with the objective to increase the potential of success for Alpine sites and to improve the representation of the Alps on the World Heritage List. This Working Group mainly focuses on transboundary and serial transnational sites and represents an example of fruitful collaboration between two international conventions. This background study aims at collecting and updating the existing analyses on the feasibility of poten- tial transboundary and serial transnational nominations. Its main findings can be summarized in the following manner: - Optimal forum. The Alpine Convention is the optimal forum to support the harmonisation of the Tentative Lists and subsequently to facilitate Alpine nominations to the World Heritage List. - Well documented. The Alpine Heritage is well documented throughout existing contributions in particular from UNESCO, UNEP/WCMC, IUCN, ICOMOS, ALPARC and EURAC. The contents of these materials are synthesized, updated and presented in the present study. - Official sources. Only official sources, made publicly available by the UNESCO World Heritage Cen- tre, were used in this study. The Tentative Lists are not always completely updated or comparable and some entries await to be completed or revised. -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region

BRIEFING EU strategy for the Alpine region SUMMARY Launched in January 2016, the European Union strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) is the fourth and most recent macro-regional strategy to be set up by the European Union. One of the biggest challenges facing the seven countries and 48 regions involved in the EUSALP is that of securing sustainable development in the macro-region, especially in its resource-rich, but highly vulnerable core mountain area. The Alps are home to a vast array of animal and plant species and constitute a major water reservoir for Europe. At the same time, they are one of Europe's prime tourist destinations, and are crossed by busy European transport routes. Both tourism and transport play a key role in climate change, which is putting Alpine natural resources at risk. The European Parliament considers that the experience of the EUSALP to date proves that the macro-regional concept can be successfully applied to more developed regions. The Alpine strategy provides a good example of a template strategy for territorial cohesion; as it simultaneously incorporates productive areas, mountainous and rural areas, and some of the most important and highly developed cities in the EU. Although there is a marked gap between urban and rural mountainous areas, the macro-region shows a high level of socio-economic interdependence, confirmed by recent research. Disparities (in terms of funding and capacity) between participating countries, a feature that has caused challenges for other EU macro-regional strategies, are less of an issue in the Alpine region, but improvements are needed and efforts should be made in view of the new 2021-2027 programming period. -

Predicting Global Population Connectivity and Targeting Conservation Action for Snow Leopard Across Its Range

Ecography 39: 419–426, 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecog.01691 © 2015 e Authors. Ecography © 2015 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Bethany Bradley. Editor-in-Chief: Miguel Araújo. Accepted 27 April 2015 Predicting global population connectivity and targeting conservation action for snow leopard across its range Philip Riordan, Samuel A. Cushman, David Mallon, Kun Shi and Joelene Hughes P. Riordan ([email protected]) and J. Hughes, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. – S. A. Cushman, US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 800 E Beckwith, Missoula, MT 59801, USA. – D. Mallon, Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, School of Science and the Environment, Manchester Metropolitan Univ., Manchester, M1 5GD, UK. – K. Shi and PR, Wildlife Inst., College of Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry Univ., 35, Tsinghua-East Road, Beijing 100083, China. Movements of individuals within and among populations help to maintain genetic variability and population viability. erefore, understanding landscape connectivity is vital for effective species conservation. e snow leopard is endemic to mountainous areas of central Asia and occurs within 12 countries. We assess potential connectivity across the species’ range to highlight corridors for dispersal and genetic flow between populations, prioritizing research and conservation action for this wide-ranging, endangered top-predator. We used resistant kernel modeling to assess snow leopard population connectivity across its global range. We developed an expert-based resistance surface that predicted cost of movement as functions of topographical complexity and land cover. e distribution of individuals was simulated as a uniform density of points throughout the currently accepted global range. -

21998A0207(01) Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 P. 0022

21998A0207(01) Protocol of Accession of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 p. 0022 - 0024 Dates: OF DOCUMENT: 20/12/1994 OF EFFECT: 00/00/0000; ENTRY INTO FORCE SEE ART 4.2 OF SIGNATURE: 20/12/1994; Chambry OF END OF VALIDITY: 99/99/9999 Authentic language: FRENCH ; GERMAN ; ITALIAN ; SLOVENIAN Author: FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY ; SPAIN ; AUSTRIA ; FRANCE ; ITALY ; LIECHTENSTEIN ; SLOVENIA ; SWITZERLAND ; EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ; MONACO Subject matter: EXTERNAL RELATIONS ; ENVIRONMENT Directory code: 11306000 ; 15102000 EUROVOC descriptor: action programme ; cross-border cooperation ; environmental protection ; international convention ; Alpine Region ; Monaco Legal basis: 192E130S-P1............... ADOPTION 192E228-P2................ ADOPTION 192E228-P3L1.............. ADOPTION pd4ml evaluation copy. visit http://pd4ml.com Amendment to: 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION TEXT FR DAT.ENT.FORCE 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION ANN FR DAT.ENT.FORCE Amended by: ADOPTED-BY.... 398D0118.......... FR 16/12/97 PROTOCOL OF ACCESSION of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC, THE PRINCIPALITY OF LIECHTENSTEIN, THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, THE SWISS CONFEDERATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, Signatories to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention),on the one hand,and THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO,on the other, WHEREAS the Principality of Monaco has requested to become a Contracting Party to the Alpine Convention, IN THEIR DESIRE to ensure the protection of the Alps throughout theentire Alpine area, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 pd4ml evaluation copy. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY

February 2019 EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY 2019 Work Programme 1. Introduction: The Alpine Region1 The Alpine Region is among the largest natural, economic and productive areas in Europe, with over 80 million inhabitants, and among the most attractive tourist regions, welcoming millions of guests per year. While trade, businesses and industry in the Alpine Region are concentrated in the main areas of settlement on the outskirts of the Alps and in the large Alpine valleys along the major traffic routes, over 40 % of the Region is not or not permanently inhabited. Due to the Alpine Region’s unique geographic and natural characteristics, it is particularly affected by several of the challenges arising in the 21st century: Economic globalisation requires sustainable and continuously high competitiveness as well as the capacity to innovate; Demographic change leads to an ageing population and outward migration of highly qualified labour; Global climate change already has noticeable effects on the environment, biodiversity and living conditions for the inhabitants of the Alpine Region; A reliable and sustainable energy supply must be ensured in the parts of the Region which are difficult to access; As a transit region in the heart of Europe and due to its geographic features, the Alpine Region requires sustainable and custom-fit traffic concepts; The Alpine Region is to be preserved as a unique natural and cultural environment. 1 This description part comes from the Bavarian 2017 Work Programme 1 February 2019 The different characteristics of peripheral areas, centers of different sizes, and metropolises, require a dialogue on a basis of equality and the development of an alliance aimed at sustainable development while respecting its needs. -

Return of a Lost Structure in the Evolution of Felid Dentition Revisited: a Devoevo Perspective on the Irreversibility of Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Return of a lost structure in the evolution of felid dentition revisited: A DevoEvo perspective on the irreversibility of evolution Vincent J. Lynch Department of Biological Sciences, University at Buffalo, SUNY, 551 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Correspondence: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Abstract There is a longstanding interest in whether the loss of complex characters is reversible (so-called “Dollo’s law”). Reevolution has been suggested for numerous traits but among the first was Kurtén (1963), who proposed that the presence of the second lower molar (M2) of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) was a violation of Dollo’s law because all other Felids lack M2. While an early and often cited example for the reevolution of a complex trait, Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) used an ad hoc parsimony argument to support their proposition that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. Here I revisit the evidence that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx using explicit parsimony and maximum likelihood models of character evolution and find strong evidence that Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) were correct – M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. -

Conservation of Snow Leopards: Spill-Over Benefits for Other Carnivores?

Conservation of snow leopards: spill-over benefits for other carnivores? J USTINE S. ALEXANDER,JEREMY J. CUSACK,CHEN P ENGJU S HI K UN and P HILIP R IORDAN Abstract In high-altitude settings of Central Asia the protection will also benefit many other species (Noss, Endangered snow leopard Panthera uncia has been recog- ; Andelman & Fagan, ). Top predators often nized as a potential umbrella species. As a first step in asses- meet this criterion (Sergio et al., ; Dalerum et al., sing the potential benefits of snow leopard conservation for ; Rozylowicz et al., ), with many large carnivores other carnivores, we sought a better understanding of the additionally possessing charismatic qualities and wide pub- presence of other carnivores in areas occupied by snow leo- lic recognition that can attract disproportionate conserva- pards in China’s Qilianshan National Nature Reserve. We tion investments (Sergio et al., ; Karanth & Chellam, used camera-trap and sign surveys to examine whether ). The flagship status of such carnivores can bring in- other carnivores were using the same travel routes as snow direct benefits to other species that are neglected or over- leopards at two spatial scales. We also considered temporal looked, by highlighting common threats and emphasizing interactions between species. Our results confirm that other their mutual dependence. A fundamental step in identifying carnivores, including the red fox Vulpes vulpes, grey wolf and quantifying potential benefits for other species is to Canis lupus, Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx and dhole Cuon alpinus, demonstrate the spatial extent of co-occurrence in the occur along snow leopard travel routes, albeit with low detec- area of interest (Andelman & Fagan, ). -

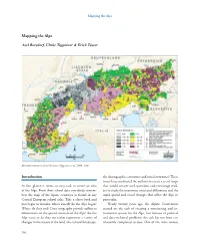

Mapping the Alps

Mapping the Alps Mapping the Alps Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser Electoral turnout in local elections (Tappeiner et al. 2008: 138). Introduction the demographic, economic and social structures? These issues have motivated the authors to create a set of maps At first glance it seems an easy task to create an atlas that would answer such questions and encourage read- of the Alps. From their school days everybody remem- ers to study the enormous structural differences and the bers the map of the alpine countries as found in any rapid spatial and social changes that affect the Alps in Central European school atlas. Take a closer look and particular. you begin to wonder: where exactly do the Alps begin? Nearly twenty years ago, the Alpine Convention Where do they end? Does orography provide sufficient started on the task of creating a monitoring and in- information on the spatial structure of the Alps? Are the formation system for the Alps, but because of political Alps static or do they not rather experience a variety of and data-technical problems this task has not been sat- changes in the nature of the land, the cultural landscape, isfactorily completed to date. One of the most serious 186 Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser problems was the harmonization of data that have been resources, but they also expose the hillsides and valleys defined in a variety of ways in the official statistics of to various dangers. individual Alpine states and moreover may have been The population in the Alps does not only face natu- gathered at different points in time.