Analysis of Mountain Areas in EU Member States, Acceding and Other European Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study

Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study 15 August 2014 Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Executive Summary The UNESCO World Heritage Committee encouraged the States Parties to harmonize their Tentative Lists of potential World Heritage Sites at the regional and thematic level. Consequently, the UNESCO World Heritage Working Group of the Alpine Convention was mandated by the Ministers to contribute to the harmo- nization of the National Tentative Lists with the objective to increase the potential of success for Alpine sites and to improve the representation of the Alps on the World Heritage List. This Working Group mainly focuses on transboundary and serial transnational sites and represents an example of fruitful collaboration between two international conventions. This background study aims at collecting and updating the existing analyses on the feasibility of poten- tial transboundary and serial transnational nominations. Its main findings can be summarized in the following manner: - Optimal forum. The Alpine Convention is the optimal forum to support the harmonisation of the Tentative Lists and subsequently to facilitate Alpine nominations to the World Heritage List. - Well documented. The Alpine Heritage is well documented throughout existing contributions in particular from UNESCO, UNEP/WCMC, IUCN, ICOMOS, ALPARC and EURAC. The contents of these materials are synthesized, updated and presented in the present study. - Official sources. Only official sources, made publicly available by the UNESCO World Heritage Cen- tre, were used in this study. The Tentative Lists are not always completely updated or comparable and some entries await to be completed or revised. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region

BRIEFING EU strategy for the Alpine region SUMMARY Launched in January 2016, the European Union strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) is the fourth and most recent macro-regional strategy to be set up by the European Union. One of the biggest challenges facing the seven countries and 48 regions involved in the EUSALP is that of securing sustainable development in the macro-region, especially in its resource-rich, but highly vulnerable core mountain area. The Alps are home to a vast array of animal and plant species and constitute a major water reservoir for Europe. At the same time, they are one of Europe's prime tourist destinations, and are crossed by busy European transport routes. Both tourism and transport play a key role in climate change, which is putting Alpine natural resources at risk. The European Parliament considers that the experience of the EUSALP to date proves that the macro-regional concept can be successfully applied to more developed regions. The Alpine strategy provides a good example of a template strategy for territorial cohesion; as it simultaneously incorporates productive areas, mountainous and rural areas, and some of the most important and highly developed cities in the EU. Although there is a marked gap between urban and rural mountainous areas, the macro-region shows a high level of socio-economic interdependence, confirmed by recent research. Disparities (in terms of funding and capacity) between participating countries, a feature that has caused challenges for other EU macro-regional strategies, are less of an issue in the Alpine region, but improvements are needed and efforts should be made in view of the new 2021-2027 programming period. -

21998A0207(01) Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 P. 0022

21998A0207(01) Protocol of Accession of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 p. 0022 - 0024 Dates: OF DOCUMENT: 20/12/1994 OF EFFECT: 00/00/0000; ENTRY INTO FORCE SEE ART 4.2 OF SIGNATURE: 20/12/1994; Chambry OF END OF VALIDITY: 99/99/9999 Authentic language: FRENCH ; GERMAN ; ITALIAN ; SLOVENIAN Author: FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY ; SPAIN ; AUSTRIA ; FRANCE ; ITALY ; LIECHTENSTEIN ; SLOVENIA ; SWITZERLAND ; EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ; MONACO Subject matter: EXTERNAL RELATIONS ; ENVIRONMENT Directory code: 11306000 ; 15102000 EUROVOC descriptor: action programme ; cross-border cooperation ; environmental protection ; international convention ; Alpine Region ; Monaco Legal basis: 192E130S-P1............... ADOPTION 192E228-P2................ ADOPTION 192E228-P3L1.............. ADOPTION pd4ml evaluation copy. visit http://pd4ml.com Amendment to: 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION TEXT FR DAT.ENT.FORCE 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION ANN FR DAT.ENT.FORCE Amended by: ADOPTED-BY.... 398D0118.......... FR 16/12/97 PROTOCOL OF ACCESSION of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC, THE PRINCIPALITY OF LIECHTENSTEIN, THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, THE SWISS CONFEDERATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, Signatories to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention),on the one hand,and THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO,on the other, WHEREAS the Principality of Monaco has requested to become a Contracting Party to the Alpine Convention, IN THEIR DESIRE to ensure the protection of the Alps throughout theentire Alpine area, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 pd4ml evaluation copy. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY

February 2019 EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY 2019 Work Programme 1. Introduction: The Alpine Region1 The Alpine Region is among the largest natural, economic and productive areas in Europe, with over 80 million inhabitants, and among the most attractive tourist regions, welcoming millions of guests per year. While trade, businesses and industry in the Alpine Region are concentrated in the main areas of settlement on the outskirts of the Alps and in the large Alpine valleys along the major traffic routes, over 40 % of the Region is not or not permanently inhabited. Due to the Alpine Region’s unique geographic and natural characteristics, it is particularly affected by several of the challenges arising in the 21st century: Economic globalisation requires sustainable and continuously high competitiveness as well as the capacity to innovate; Demographic change leads to an ageing population and outward migration of highly qualified labour; Global climate change already has noticeable effects on the environment, biodiversity and living conditions for the inhabitants of the Alpine Region; A reliable and sustainable energy supply must be ensured in the parts of the Region which are difficult to access; As a transit region in the heart of Europe and due to its geographic features, the Alpine Region requires sustainable and custom-fit traffic concepts; The Alpine Region is to be preserved as a unique natural and cultural environment. 1 This description part comes from the Bavarian 2017 Work Programme 1 February 2019 The different characteristics of peripheral areas, centers of different sizes, and metropolises, require a dialogue on a basis of equality and the development of an alliance aimed at sustainable development while respecting its needs. -

Mapping the Alps

Mapping the Alps Mapping the Alps Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser Electoral turnout in local elections (Tappeiner et al. 2008: 138). Introduction the demographic, economic and social structures? These issues have motivated the authors to create a set of maps At first glance it seems an easy task to create an atlas that would answer such questions and encourage read- of the Alps. From their school days everybody remem- ers to study the enormous structural differences and the bers the map of the alpine countries as found in any rapid spatial and social changes that affect the Alps in Central European school atlas. Take a closer look and particular. you begin to wonder: where exactly do the Alps begin? Nearly twenty years ago, the Alpine Convention Where do they end? Does orography provide sufficient started on the task of creating a monitoring and in- information on the spatial structure of the Alps? Are the formation system for the Alps, but because of political Alps static or do they not rather experience a variety of and data-technical problems this task has not been sat- changes in the nature of the land, the cultural landscape, isfactorily completed to date. One of the most serious 186 Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser problems was the harmonization of data that have been resources, but they also expose the hillsides and valleys defined in a variety of ways in the official statistics of to various dangers. individual Alpine states and moreover may have been The population in the Alps does not only face natu- gathered at different points in time. -

The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-09-16 The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices Benjamin, Mary Wilder Benjamin, M. W. (2014). The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28251 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1767 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices by Mary Wilder Benjamin A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2014 © Mary Wilder Benjamin 2014 Abstract Recreational mountaineering is a complex pursuit that continues to evolve with respect to demographics, participant numbers, methods, equipment, and the nature of the experience sought. The activity often occurs in protected areas where agency managers are charged with the inherently conflicting mandate of protecting the natural environment and facilitating high quality recreational experiences. Effective management of such mountaineering environs is predicated on meaningful understanding of the users’ motivations, expectations and behaviours. -

* Council of * Conseil De L'

Naturona * COUNCIL OF * CONSEIL DE L’ Naturopa N°72-1993 : : Editorial V. Bossevski 3 What future for our mountains? W. Bätzing 4 Managing this vulnerable environment P. Messerli 6 The Rhodope Mountains. Jewel of Bulgaria J. Danchev 8 * * * Mountainous perspectives. Lessons from history E. Lichtenberger 9 CENTRE An ecological approach P. Stoll 11 NATUROPA Living nature P. Ozenda 12 The Alpine Convention U. Tödter 14 In Italy F. Bartaletti 15 A blessing in disguise? A. Gosar 20 Editorial Teberda A.M. Amirkhanov, N. N. Polivanova 22 he Balkans represent a vast mountai and species endemic to the Balkans such as altitude run to 2,000 m. There are between nous universe with a natural environ the Pinus peuce. Coniferous bushes and 1,700 and 1,850 higher plant species and Delights in the heights H. Haid 23 T ment very similar to that of the Alps, Siberian junipers grow above the forests, between 170 and 200 species of vertebrates. the Appenines and the Carpathians, but with rocky Alpine meadows dotted with small Out of the 50 protected areas in Bulgaria on Naturopa is published in English, Wise use of natural resources F. Sieren, P. F. Sieben 24 which also has its own special features. The glaciers at the summits and peaks. the United Nations’ list of national parks, 40 French, German, Italian, Spanish and proximity of Asia has enriched its fauna and are in the mountains. Portuguese by the Centre Naturopa of the Mountaineering: protection first J. Klenner 26 flora, but it is the species and populations Mountain conservation in Bulgaria dates Council of Éurope, F-67075 Strasbourg typical of the Balkans alone that make it from the last century. -

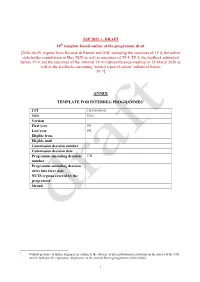

ASP 2021 +: DRAFT 10 Template Based Outline of the Programme Draft [2020-06-29, Experts from Rosinak & Partner and OIR; Incl

ASP 2021 +: DRAFT 10th template based outline of the programme draft [2020-06-29, experts from Rosinak & Partner and OIR; including the outcomes of TF 8, the online stakeholder consultation in May 2020 as well as outcomes of TF 4, TF 5, the feedback submitted before TF-6 and the outcomes of the informal TF-6 videoconference-meeting on 26 March 2020 as well as the feedback concerning “related types of action” submitted before TF 7] ANNEX TEMPLATE FOR INTERREG PROGRAMMES1 CCI [15 characters] Title [255] Version First year [4] Last year [4] Eligible from Eligible until Commission decision number Commission decision date Programme amending decision [20] number Programme amending decision entry into force date NUTS regions covered by the programme Strand 1 Without prejudice to further alignment in relation to the outcome of interinstitutional negotiations on the articles of the CPR and the fund-specific regulations. Alignments on the external Interreg programmes still to follow. 1 1. Programme strategy: main development challenges and policy responses 1.1. Programme area (not required for Interreg C programmes) Reference: Article 17(4)(a), Article 17(9)(a) Text field [2 000] Status from TF-meeting 8: The program area for the Alpine Space Programme 2021-2027 preliminary comprises the following territories: Austria: the whole territory France – NUTS 2: Alsace*, Franche-Comté, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Rhône-Alpes Germany – NUTS 2: Oberbayern, Niederbayern**, Oberpfalz**, Oberfranken**, Mittelfranken**, Unterfranken**, Schwaben; Stuttgart**, Karlsruhe**, Freiburg, Tübingen Italy – NUTS 2: Lombardia, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano / Bozen, Valle d‘Aosta / Vallée d'Aoste, Piemonte, Liguria Liechtenstein: the whole territory Slovenia: the whole territory Switzerland: the whole territory. -

Via Alpina and Ruperti Trail

VIA ALPINA AND RUPERTI TRAIL THE LONG DISTANCE HIKING LOOP THROUGH 5 NATIONAL PARKS AND 3 COUNTRIES Editor and Publisher: National Secretariat Via Alpina Austria and Germany, Department of Spatial Planning and Nature Conservation of the Austrian Alpine Association (OeAV) Texts: Triglav National Park Management, Gesäuse National Park Management, Kalkalpen National Park Management, Berchtesgaden National Park Management, Hohe Tauern National Park Management, Via Alpina National Secretariat Austria and Germany, Peter Šilak, Franz Genger, Rudi Felber, Arnold Kreditsch, Susanne Schwab, Erika and Fritz Käfer, Christina Schwann Extracts from the OeAV (Austrian Alpine Association) yearbooks of 1961, 1968, 1976, hiking guide “Österreichischer Weitwanderweg 10 (Rupertiweg)” (Austrian Long-Dis- tance Hiking Trail 10, Ruperti Trail) by Erika and Fritz Käfer, privately published by the long-distance hiking section of the Austrian Alpine Association, 2007. Translations: German - English: Markus Wieland, Steve Tomlin Maps: Latitude-Cartagène / Geosys-Mona / Teleatlas / Network of Alpine protected areas, Randonnées Créations (Jean-Philippe Repiquet), Art’Graphi Créations (Sophie Simon) Reproduction with consent from the BEV – Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen (Federal Office for Calibration and Measurement) in Vienna, EB 2008/00307, p. 32. Layout and Graphic Design: Christina Schwann - National Secretariat Via Alpina Austria and Germany, Department of Spatial Planning and Nature Conservation of the Austrian Alpine Association (OeAV) Printing: Samson Druck GmbH - St. Margarethen Cover Pictures: f.l.: “View on the Königssee with the Watzmann east wall” – Berchtesgaden National Park Management; “Reißeck balcony trail” – G. Mussnig, Hohe Tauern National Park Management – Carinthia; The “Goldlochquelle” (Golden Lair Fountain) – F. Sieghartsleitner, Kalkalpen National Park Management; “On the top of the Črna prst” – F. -

Management of Large Carnivores in the Alps

BRIEFING Requested by the ENVI committee Overcoming barriers – management of large carnivores in the Alps KEY FINDINGS After centuries of intensive hunting large carnivores like brown bears, Eurasian lynx and wolves are now recovering in many areas of Europe. This work deals with large carnivore populations in the French Alps focusing on wolf and gives information on the recent population status, management, legal frameworks and recommendations for habitat protection and coexistence of humans and large carnivores. The occurrence of wolves in France is limited to the Western Central Alps. In 2017 52 packs (360 individuals) were monitored. The Western Alpine population is of Italian origin, and migration moving from the Apennines to the Alpine population is still underway. Wolf populations are still far from being accepted by local farmers and livestock breeders, and conflicts with hunters are also reported. A French wolf plan exists. The actions listed in the wolf plan are based on livestock protection and compensations. The principles of “tir de défense” (removal of stock raiding individuals) and “tir de prélèvement” (a yearly defined number of individuals are removed) are applied. The goal is to reduce predation and keep or increase wolf populations and maintain them at favourable conservation status. Lynx is present in France in the Jura, the Vosges-Palatinian region and in the Alps. The alpine population originates from the Carpathians, where the nearest autochthonous population can be found. In 2016 100 individuals lived in France, and a small population of around 30 individuals has settled in the North of the French Alps (Savoie). For the lynx no management plan exists. -

AGROVOC Semantic Data Interoperability on Food and Agriculture AGROVOC Semantic Data Interoperability on Food and Agriculture

AGROVOC Semantic data interoperability on food and agriculture AGROVOC Semantic data interoperability on food and agriculture Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 ii Required citation: The designations employed and the presentation of material in this FAO. 2021. AGROVOC – Semantic information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever data interoperability on food on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and agriculture. Rome. (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city https://doi.org/10.4060/cb2838en or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-133831-5 © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC- SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

Water and Water Management Issues Alpine Convention | Water and Water Management Issues 43

www.alpconv.org WATER AND WATER MANAGEMENT ISSUES Report on the State of the Alps ALPINE CONVENTION Alpine Signals - Special Edition 2 SUMMARY Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention www.alpconv.org [email protected] Offi ce: Herzog-Friedrich-Strasse 15 A-6020 Innsbruck Austria Branch offi ce: Viale Druso-Drususallee 1 I-39100 Bolzano-Bozen Italy Imprint Editor: Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention Viale Druso-Drususallee 1 I-39100 Bolzano-Bozen Italy Graphic design and print: Karo Druck KG/SAS Eppan/Appiano–Bolzano, Bozen (I) Cover Photo: Magnifi cent aquamarine waters of the Socˇa River source, Slovenia. © Albert Kolar, ARSO, SOKOL © Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention, 2009 ISBN 978-8-89-043483-9 WATER AND WATER MANAGEMENT ISSUES Report on the State of the Alps ALPINE CONVENTION Alpine Signals – Special edition 2 SUMMARY ALPINE CONVENTION | WATER AND WATER MANAGEMENT ISSUES The present report has been approved by the Xth Alpine Conference, held in Evian (France) 12 March 2009. It has been elaborated by the Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention in conjunction with an ad-hoc expert group chaired jointly by Austria and Germany, in coordination with the French Presidency of the Alpine Conference. Stakeholders from the science world and relevant NGOs have also contributed to the report. A written contribution to the Climate Chapter has been made by Lucˇka Kajfež-Bogataj, Univerza v Ljubljani, Biotehnisˇka fakulteta, Ljubljana (University of Ljubljana, Biotehnical faculty, Ljubljana). The establishment and layout of the maps were done by Ingrid Roder, Umweltbundesamt Austria The text of the summary was drafted by the Austrian Presidency of the ad-hoc expert group, in coordination with the Permanent Secretariat and the members of the ad-hoc expert group.