The Challenge of the Alpine Convention and the “Strange Case” of the Andean Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Act of Carabobo

Law and Business Review of the Americas Volume 8 Number 1 Article 16 2002 Documentation: The Act of Carabobo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra Recommended Citation Documentation: The Act of Carabobo, 8 LAW & BUS. REV. AM. 309 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/lbra/vol8/iss1/16 This Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law and Business Review of the Americas by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Winter/Spring 2002 309 Documentation: The Act of Carabobo* Table of Contents I. Political Cooperation in the Sphere of Integration II. Andean Social Agenda IIl. Andean Common Market IV. Common Foreign Policy V. Border Integration and Development Policy The Presidents of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, and the Chairman of Peru's Ministerial Council, gathered in the city of Valencia, Venezuela on June 23 and 24, 2001 to meet in the Thirteenth Andean Presidential Council, underscored the impor- tance to the five Andean countries of holding this Council during the celebration of the 180th anniversary of the Battle of Carabobo, the event that consecrated Venezuela's inde- pendence, and provided the motivating force for the great Latin American independence campaign. In reaffirming their unswerving commitment to continue moving toward more advanced forms of integration in order to fulfill the historic vocation of their nations, the Presidents: 1. Noted with satisfaction that the Andean Community has continued to intensify its economic integration and strengthen its international presence; has broad- ened its Community agenda to encompass new spheres of action, like the polit- ical and social; and that the Andean business and labor sectors are becoming increasingly committed to the integration process. -

Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study

Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Alpine Sites and the UNESCO World Heritage Background Study 15 August 2014 Alpine Convention WG UNESCO World Heritage Background study Executive Summary The UNESCO World Heritage Committee encouraged the States Parties to harmonize their Tentative Lists of potential World Heritage Sites at the regional and thematic level. Consequently, the UNESCO World Heritage Working Group of the Alpine Convention was mandated by the Ministers to contribute to the harmo- nization of the National Tentative Lists with the objective to increase the potential of success for Alpine sites and to improve the representation of the Alps on the World Heritage List. This Working Group mainly focuses on transboundary and serial transnational sites and represents an example of fruitful collaboration between two international conventions. This background study aims at collecting and updating the existing analyses on the feasibility of poten- tial transboundary and serial transnational nominations. Its main findings can be summarized in the following manner: - Optimal forum. The Alpine Convention is the optimal forum to support the harmonisation of the Tentative Lists and subsequently to facilitate Alpine nominations to the World Heritage List. - Well documented. The Alpine Heritage is well documented throughout existing contributions in particular from UNESCO, UNEP/WCMC, IUCN, ICOMOS, ALPARC and EURAC. The contents of these materials are synthesized, updated and presented in the present study. - Official sources. Only official sources, made publicly available by the UNESCO World Heritage Cen- tre, were used in this study. The Tentative Lists are not always completely updated or comparable and some entries await to be completed or revised. -

Secure Passports from De La Rue

SECURE PASSPORTS FROM DE LA RUE DE LA RUE IDENTITY SYSTEMS Complete solutions to design, produce, personalise and program passports, conforming to all the recommendations of ICAO, the European Union and the US visa waiver programme. If you would like to receive a copy of our ‘Secure Passports’ brochure then please call +44 (0)1256 605259, or send an email to [email protected] A trusted partner in major projects worldwide ICAO MRTD REPORT • 1 ICAO MRTD Report Vol. 1, No. 1, 2006 Table of contents Editor: Mary McMunn Content Coordinator: Mauricio Siciliano Graphic Art Design: Sylvie Schoufs, Editor’s welcome . .2 FCM Communications Inc. Published by: Message from the President of the Council, International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Dr. Assad Kotaite . .5 999 University Street Montréal, Québec Canada H3C 5H7 Message from the Secretary Telephone: +1 (514) 954-8219 ext. 7068 General, Dr.Taïeb Chérif . .7 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.icao.int/mrtd ICAO Hosts Symposium on The objective of the ICAO MRTD Report is to pro- MRTDs and Biometrics . .8 vide a comprehensive account of new develop- ments, trends, innovations and applications in the field of MRTDs to the Contracting States of ICAO ICAO Doctrine on Travel and the international aeronautical and security Documents . worlds. 12 Copyright © 2006 International Civil Aviation TAG-MRTD 16th Meeting . .16 Organization. Unsigned material may be repro- duced in full or in part provided that it is accom- panied by reference to the ICAO MRTD Report; for Machine Readable Travel Documents rights to reproduced signed articles, please write to the editor. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region

BRIEFING EU strategy for the Alpine region SUMMARY Launched in January 2016, the European Union strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) is the fourth and most recent macro-regional strategy to be set up by the European Union. One of the biggest challenges facing the seven countries and 48 regions involved in the EUSALP is that of securing sustainable development in the macro-region, especially in its resource-rich, but highly vulnerable core mountain area. The Alps are home to a vast array of animal and plant species and constitute a major water reservoir for Europe. At the same time, they are one of Europe's prime tourist destinations, and are crossed by busy European transport routes. Both tourism and transport play a key role in climate change, which is putting Alpine natural resources at risk. The European Parliament considers that the experience of the EUSALP to date proves that the macro-regional concept can be successfully applied to more developed regions. The Alpine strategy provides a good example of a template strategy for territorial cohesion; as it simultaneously incorporates productive areas, mountainous and rural areas, and some of the most important and highly developed cities in the EU. Although there is a marked gap between urban and rural mountainous areas, the macro-region shows a high level of socio-economic interdependence, confirmed by recent research. Disparities (in terms of funding and capacity) between participating countries, a feature that has caused challenges for other EU macro-regional strategies, are less of an issue in the Alpine region, but improvements are needed and efforts should be made in view of the new 2021-2027 programming period. -

Alpcity Project Final Report

This project has received the European Regional Development Funding through the Interreg IIIB Community Initiative Interreg III B Local endogenous development and urban regeneration of small alpine towns AlpCity Project Final Report A trans-national project implemented by in collaboration with Local endogenous development and urban regeneration of small alpine towns AlpCity Project Final Report Regional Budget Planning and Statistics Division 8.3 Interreg III B AlpCity Office via Lagrange, 24 10123 Turin tel. +39 011 432 5350 fax +39 011 432 5560 e-mail: [email protected] www.alpcity.it Editor: Antonella Convertino © Regione Piemonte - October 2006 acknowledgements The AlpCity Final Report is part of the final output of an EU co-founded trans-national project promoted by Piedmont Region as Lead Partner and coordinated by a team led by DANIELA SENA (Project Manager) and com- prising ANNA MARIA CAPUTANO (Project Assistant), ANTONELLA CONVERTINO (Reporting Assistant), VALENTINA SCIONERI and MAUD TRONCHIN (I&P Assistants). The work was carried out under the overall direction of MARIA CAVALLO PERIN, Piedmont Region officer in charge of the AlpCity Project and with the support of GIUSEPPE BENEDETTO, ad interim director of the Piedmont Regional Budget Planning and Statistics Division. A special thank to Franco AMATO, former director of the mentioned Division and to CORRADO DORE, AlpCity legal officer. Great support was provided by the Managing Authority (special thanks to CHRISTIAN SALLETMAIER and to CHRISTINA BAUER), the Joint Technical Secretariat (special thanks to ANTONIA LEITZ, MICHELA CAVALLINI and IVAN CURZOLO), the Italian National Contact Point Team and the German National Contact Point (special thanks to Florian Ballnus). -

1349345* Cmw/C/Per/1

United Nations CMW/C/PER/1 International Convention on the Distr.: General 4 December 2013 Protection of the Rights of English All Migrant Workers and Original: Spanish Members of Their Families Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 73 of the Convention Initial reports of States parties due in 2007 Peru* [14 August 2013] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.13-49345 (EXT) *1349345* CMW/C/PER/1 Contents Page I Introduction................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Information of a general nature..................................................................................................... 5 A. Constitutional, legislative, judicial and administrative framework governing the implementation of the Convention, and any bilateral, regional or multilateral agreements in the field of migration made by the State party.................................................................. 5 B. Information about the nature and character of migration flows (immigration, transit and emigration)..................................................................................................................... 16 C. Present situation regarding the practical application of the Convention in the reporting State ..................................................................................................................................... -

21998A0207(01) Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 P. 0022

21998A0207(01) Protocol of Accession of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps Official Journal L 033 , 07/02/1998 p. 0022 - 0024 Dates: OF DOCUMENT: 20/12/1994 OF EFFECT: 00/00/0000; ENTRY INTO FORCE SEE ART 4.2 OF SIGNATURE: 20/12/1994; Chambry OF END OF VALIDITY: 99/99/9999 Authentic language: FRENCH ; GERMAN ; ITALIAN ; SLOVENIAN Author: FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY ; SPAIN ; AUSTRIA ; FRANCE ; ITALY ; LIECHTENSTEIN ; SLOVENIA ; SWITZERLAND ; EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ; MONACO Subject matter: EXTERNAL RELATIONS ; ENVIRONMENT Directory code: 11306000 ; 15102000 EUROVOC descriptor: action programme ; cross-border cooperation ; environmental protection ; international convention ; Alpine Region ; Monaco Legal basis: 192E130S-P1............... ADOPTION 192E228-P2................ ADOPTION 192E228-P3L1.............. ADOPTION pd4ml evaluation copy. visit http://pd4ml.com Amendment to: 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION TEXT FR DAT.ENT.FORCE 296A0312(01)......AMENDMENT..... COMPLETION ANN FR DAT.ENT.FORCE Amended by: ADOPTED-BY.... 398D0118.......... FR 16/12/97 PROTOCOL OF ACCESSION of the Principality of Monaco to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY, THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC, THE PRINCIPALITY OF LIECHTENSTEIN, THE REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA, THE SWISS CONFEDERATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, Signatories to the Convention on the Protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention),on the one hand,and THE PRINCIPALITY OF MONACO,on the other, WHEREAS the Principality of Monaco has requested to become a Contracting Party to the Alpine Convention, IN THEIR DESIRE to ensure the protection of the Alps throughout theentire Alpine area, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS: Article 1 pd4ml evaluation copy. -

June/ July Summary 11/06-14/06 Copy Date: 14.07.2006

June/ July Summary 11/06-14/06 Copy date: 14.07.2006 DYNALP²: Sustainable Development at town level Contents Within the framework of the project “Future in the Alps“, experts have gathered DYNALP²: Sustainable exhaustive knowledge about sustainable development in the Alps. The implementation of this knowledge is the objective of the new project DYNALP2, Development at town level that was launched by the “Alliance in the Alps“, a network of local authorities. ........................................ 1 ...................................................................................................... more on page 1 Brain Drain and Brain Gain Brain Drain and Brain Gain in peripheral regions in peripheral regions ........ 2 Know-how for the Alps The focus of the 2003 - 2007 “Brain Drain – Brain Gain“ Project is the online............................... 2 development, introduction and evaluation of action plans that reduce the migration of skilled labour from peripheral regions and instead favour migration Future research and into these areas. ........................................................................... more on page 2 transnational cooperation in the Alps .......................... 2 Mountain Convention: Cohesion towards growth Negotiable land use The fifth European Mountain Convention will take place on 14 and 15 September certificates ...................... 2 in Chaves in Portugal. It is organised by Euromontana, the European Association of Mountain Territories and its slogan is “Cohesion for growth – mountains as Mountain Convention: natural ingredients for Europe’s competitiveness “. ..................... more on page 3 Cohesion towards growth 3 Is mountain milk more valuable? ......................... 3 Austria: Federation money DYNALP²: Sustainable Development at town level for the implementation of the Alpine Convention ..... 3 (14.06.2006) Within the framework of the project “Future in the Alps“, experts Management and Winter have gathered exhaustive knowledge about sustainable development in the Alps. -

EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY

February 2019 EU Strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP) ITALIAN PRESIDENCY 2019 Work Programme 1. Introduction: The Alpine Region1 The Alpine Region is among the largest natural, economic and productive areas in Europe, with over 80 million inhabitants, and among the most attractive tourist regions, welcoming millions of guests per year. While trade, businesses and industry in the Alpine Region are concentrated in the main areas of settlement on the outskirts of the Alps and in the large Alpine valleys along the major traffic routes, over 40 % of the Region is not or not permanently inhabited. Due to the Alpine Region’s unique geographic and natural characteristics, it is particularly affected by several of the challenges arising in the 21st century: Economic globalisation requires sustainable and continuously high competitiveness as well as the capacity to innovate; Demographic change leads to an ageing population and outward migration of highly qualified labour; Global climate change already has noticeable effects on the environment, biodiversity and living conditions for the inhabitants of the Alpine Region; A reliable and sustainable energy supply must be ensured in the parts of the Region which are difficult to access; As a transit region in the heart of Europe and due to its geographic features, the Alpine Region requires sustainable and custom-fit traffic concepts; The Alpine Region is to be preserved as a unique natural and cultural environment. 1 This description part comes from the Bavarian 2017 Work Programme 1 February 2019 The different characteristics of peripheral areas, centers of different sizes, and metropolises, require a dialogue on a basis of equality and the development of an alliance aimed at sustainable development while respecting its needs. -

Mapping the Alps

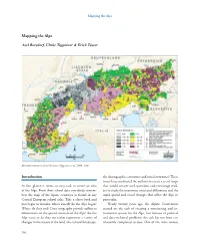

Mapping the Alps Mapping the Alps Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser Electoral turnout in local elections (Tappeiner et al. 2008: 138). Introduction the demographic, economic and social structures? These issues have motivated the authors to create a set of maps At first glance it seems an easy task to create an atlas that would answer such questions and encourage read- of the Alps. From their school days everybody remem- ers to study the enormous structural differences and the bers the map of the alpine countries as found in any rapid spatial and social changes that affect the Alps in Central European school atlas. Take a closer look and particular. you begin to wonder: where exactly do the Alps begin? Nearly twenty years ago, the Alpine Convention Where do they end? Does orography provide sufficient started on the task of creating a monitoring and in- information on the spatial structure of the Alps? Are the formation system for the Alps, but because of political Alps static or do they not rather experience a variety of and data-technical problems this task has not been sat- changes in the nature of the land, the cultural landscape, isfactorily completed to date. One of the most serious 186 Axel Borsdorf, Ulrike Tappeiner & Erich Tasser problems was the harmonization of data that have been resources, but they also expose the hillsides and valleys defined in a variety of ways in the official statistics of to various dangers. individual Alpine states and moreover may have been The population in the Alps does not only face natu- gathered at different points in time. -

Andean Community of Nations

5(*,21$/675$7(*<$1'($1&20081,7<2)1$7,216 1 $FURQ\PV1 ACT Amazonian Cooperation Treaty AEC Project for the establishment of an common external tariff for the Andean States AIS Andean Integration System (comprises all the Andean regional institutions) ALADI Latin American Integration Association (Member States of Mercosur, the Andean Pact and Mexico, Chile and Cuba) ALALC Latin American Free Trade Association, replaced by ALADI in 1980 ALA Reg. Council Regulation (EEC) No 443/92 of 25 February 1992 on technical and financial and economic cooperation with the countries of Asia and Latin America ALFA Latin American Academic Training Programme ALINVEST Latin American investment programme for the promotion of relations between SMEs @LIS Latin American Information Society Programme APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (21 members)2 APIR Project for the acceleration of the regional integration process ARIP Andean Regional Indicative Programme ATPA Andean Trade Preference Act CACM Central American Common Market: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras CAF Andean Development Corporation CALIDAD Andean regional project on quality standards CAN Andean Community of Nations: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela + AIS CAPI Andean regional project for the production of agricultural and industrial studies CARICOM3 Caribbean Community DAC Development Assistance Committee of the OECD DC Developing country DFI Direct foreign investment DG Directorate-General DIPECHO ECHO Disaster Preparedness Programme EC European Community ECHO -

Trade, Regional Integration, and Free Movement of People

A New Atlantic Community: The European Union, the US and Latin America, ed. Joaquín Roy (Miami: European Union Center of Excellence/Jean Monnet Chair, University of Miami, 2015) 111-21 Trade, Regional Integration, and Free Movement of People Willem Maas York University / European University Institute1 Abstract A building block of regional integration in Europe has been the development of supranational rights, particularly the rights of citizens of member states to live elsewhere in the community. Since the first free movement rights in the early 1950s, the concept of a common EU citizenship has hardened into law, most fa- mously in the Court of Justice’s oft-repeated assertion that “Union citizenship is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States.” By con- trast, efforts to foster the free movement of people in groupings such as CARICOM, the Andean Community, MERCOSUR, and UNASUR have so far been relatively modest. Nevertheless, actors within each of those organizations have or are considering supranational rights, thus it is useful to ask about the pro- spects of common free movement rights and perhaps eventually citizenship, fo- cused foremost on the right of member state nationals to live and work elsewhere within the community. The paper’s underlying argument is that successful and stable regional integration efforts must include free movement rights for people. Introduction In a speech at Yale University about the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) currently being negotiated between Europe and the United States, the European Commission Vice-President Viviane Reding argued that “a single market requires fundamental changes in which nation states cooperate.