Periodic Review of Animal Species Included in the CITES Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

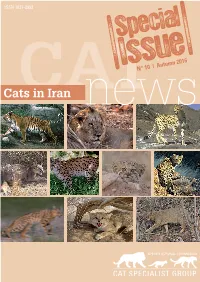

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Predicting Global Population Connectivity and Targeting Conservation Action for Snow Leopard Across Its Range

Ecography 39: 419–426, 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecog.01691 © 2015 e Authors. Ecography © 2015 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Bethany Bradley. Editor-in-Chief: Miguel Araújo. Accepted 27 April 2015 Predicting global population connectivity and targeting conservation action for snow leopard across its range Philip Riordan, Samuel A. Cushman, David Mallon, Kun Shi and Joelene Hughes P. Riordan ([email protected]) and J. Hughes, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. – S. A. Cushman, US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 800 E Beckwith, Missoula, MT 59801, USA. – D. Mallon, Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, School of Science and the Environment, Manchester Metropolitan Univ., Manchester, M1 5GD, UK. – K. Shi and PR, Wildlife Inst., College of Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry Univ., 35, Tsinghua-East Road, Beijing 100083, China. Movements of individuals within and among populations help to maintain genetic variability and population viability. erefore, understanding landscape connectivity is vital for effective species conservation. e snow leopard is endemic to mountainous areas of central Asia and occurs within 12 countries. We assess potential connectivity across the species’ range to highlight corridors for dispersal and genetic flow between populations, prioritizing research and conservation action for this wide-ranging, endangered top-predator. We used resistant kernel modeling to assess snow leopard population connectivity across its global range. We developed an expert-based resistance surface that predicted cost of movement as functions of topographical complexity and land cover. e distribution of individuals was simulated as a uniform density of points throughout the currently accepted global range. -

Return of a Lost Structure in the Evolution of Felid Dentition Revisited: a Devoevo Perspective on the Irreversibility of Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Return of a lost structure in the evolution of felid dentition revisited: A DevoEvo perspective on the irreversibility of evolution Vincent J. Lynch Department of Biological Sciences, University at Buffalo, SUNY, 551 Cooke Hall, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Correspondence: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429820; this version posted February 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RUNNING HEAD: LYNX M2 AND IRREVERSIBILE EVOLUTION Abstract There is a longstanding interest in whether the loss of complex characters is reversible (so-called “Dollo’s law”). Reevolution has been suggested for numerous traits but among the first was Kurtén (1963), who proposed that the presence of the second lower molar (M2) of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) was a violation of Dollo’s law because all other Felids lack M2. While an early and often cited example for the reevolution of a complex trait, Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) used an ad hoc parsimony argument to support their proposition that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. Here I revisit the evidence that M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx using explicit parsimony and maximum likelihood models of character evolution and find strong evidence that Kurtén (1963) and Werdelin (1987) were correct – M2 reevolved in Eurasian lynx. -

Conservation of Snow Leopards: Spill-Over Benefits for Other Carnivores?

Conservation of snow leopards: spill-over benefits for other carnivores? J USTINE S. ALEXANDER,JEREMY J. CUSACK,CHEN P ENGJU S HI K UN and P HILIP R IORDAN Abstract In high-altitude settings of Central Asia the protection will also benefit many other species (Noss, Endangered snow leopard Panthera uncia has been recog- ; Andelman & Fagan, ). Top predators often nized as a potential umbrella species. As a first step in asses- meet this criterion (Sergio et al., ; Dalerum et al., sing the potential benefits of snow leopard conservation for ; Rozylowicz et al., ), with many large carnivores other carnivores, we sought a better understanding of the additionally possessing charismatic qualities and wide pub- presence of other carnivores in areas occupied by snow leo- lic recognition that can attract disproportionate conserva- pards in China’s Qilianshan National Nature Reserve. We tion investments (Sergio et al., ; Karanth & Chellam, used camera-trap and sign surveys to examine whether ). The flagship status of such carnivores can bring in- other carnivores were using the same travel routes as snow direct benefits to other species that are neglected or over- leopards at two spatial scales. We also considered temporal looked, by highlighting common threats and emphasizing interactions between species. Our results confirm that other their mutual dependence. A fundamental step in identifying carnivores, including the red fox Vulpes vulpes, grey wolf and quantifying potential benefits for other species is to Canis lupus, Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx and dhole Cuon alpinus, demonstrate the spatial extent of co-occurrence in the occur along snow leopard travel routes, albeit with low detec- area of interest (Andelman & Fagan, ). -

The Threatening but Unpredictable Sarcoptes Scabiei: First Deadly Outbreak in the Himalayan Lynx, Lynx Lynx Isabellinus, from Pa

Hameed et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:402 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1685-0 LETTER TO THE EDITOR Open Access The threatening but unpredictable Sarcoptes scabiei: first deadly outbreak in the Himalayan lynx, Lynx lynx isabellinus, from Pakistan Khalid Hameed1,2, Samer Angelone-Alasaad3,4* , Jaffar Ud Din5,6, Muhammad Ali Nawaz7 and Luca Rossi8 Abstract Although neglected, the mite Sarcoptes scabiei is an unpredictable emerging parasite, threatening human and animal health globally. In this paper we report the first fatal outbreak of sarcoptic mange in the endangered Himalayan lynx (Lynx lynx isabellinus) from Pakistan. A 10-year-old male Himalayan lynx was found in a miserable condition with severe crusted lesions in Chitral District, and immediately died. Post-mortem examination determined high S. scabiei density (1309 mites/cm2 skin). It is most probably a genuine emergence, resulting from a new incidence due to the host-taxon derived or prey-to-predator cross-infestation hypotheses, and less probable to be apparent emergence resulting from increased infection in the Himalayan lynx population. This is an alarming situation for the conservation of this already threatened population, which demands surveillance for early detection and eventually rescue and treatment of the affected Himalayan lynx. Keywords: Sarcoptes scabiei, Lynx lynx isabellinus, Human-lynx conflict, Chitral District, Pakistan, Neglected parasite, Emerging disease Letter to the editor threatened. The last population assessment reported Although affecting more than 100 species of mammals sporadic occurrence with a minimum of six individuals worldwide [1, 2], the epidemiology of Sarcoptes scabiei is [7]. The prime threats to the existence of the Himalayan still not well understood, with differences between lynx are retaliatory killing because of human-lynx con- locations and host species [3]. -

Eurasian Lynx Reintroduction in Scotland

ECOS 33(1) 2012 ECOS 33(1) 2012 Back in 2001 Roger Sidaway commented the “real debate is about redefining the rights and responsibilities of ownership, invigorating rural economies and restoring Letting the cat out of biodiversity while the rhetorical debate is more concerned with righting the wrongs of the Clearances or attacking the conspicuous consumption of the landed gentry.” This still stands true today. For the time being I do not think the landed gentry have the bag: Eurasian lynx too much to worry about. References reintroduction in Scotland 1. Hunter J. (2000) The Making of the Crofting Community. Birlinn Ltd. Edinburgh 2. Devine T. M. (1994) Clanship to Crofters’ War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester University Press: Manchester and New York Conservation, game and land owning bodies have recently been discussing the 3. MacDonald S. (1997) Reimagining Culture: Histories, Identities and the Gaelic Renaissance. Berg: Oxford and New York conditions for any future reintroduction of lynx to Scotland. This article considers the 4. McIntosh A. (2004) Soil and Soul: People versus Corporate Power. Aurum Press Ltd. London debate amongst organisations who would be central to the possible return of the lynx. 5. Cramb A. (2000) Who owns Scotland Now? The Use and Abuse of Private Land. Mainstream Publishing: Edinburgh and London JAMES THOMSON 6. Woodin T., Crook D. and Carpentier V. (2010) Community and mutual ownership: a historical review. Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York In August 2011 it was announced that Mar Lodge estate, managed by the National 7. Chenevix-Trench H. and Philip L. J (2001) Community and conservation land ownership in highland Trust for Scotland (NTS), could face financial penalties from Scottish Natural Heritage Scotland: A common focus in s changing context. -

Management of Large Carnivores in the Alps

BRIEFING Requested by the ENVI committee Overcoming barriers – management of large carnivores in the Alps KEY FINDINGS After centuries of intensive hunting large carnivores like brown bears, Eurasian lynx and wolves are now recovering in many areas of Europe. This work deals with large carnivore populations in the French Alps focusing on wolf and gives information on the recent population status, management, legal frameworks and recommendations for habitat protection and coexistence of humans and large carnivores. The occurrence of wolves in France is limited to the Western Central Alps. In 2017 52 packs (360 individuals) were monitored. The Western Alpine population is of Italian origin, and migration moving from the Apennines to the Alpine population is still underway. Wolf populations are still far from being accepted by local farmers and livestock breeders, and conflicts with hunters are also reported. A French wolf plan exists. The actions listed in the wolf plan are based on livestock protection and compensations. The principles of “tir de défense” (removal of stock raiding individuals) and “tir de prélèvement” (a yearly defined number of individuals are removed) are applied. The goal is to reduce predation and keep or increase wolf populations and maintain them at favourable conservation status. Lynx is present in France in the Jura, the Vosges-Palatinian region and in the Alps. The alpine population originates from the Carpathians, where the nearest autochthonous population can be found. In 2016 100 individuals lived in France, and a small population of around 30 individuals has settled in the North of the French Alps (Savoie). For the lynx no management plan exists. -

Lynx Reintroduction JUNE 2014

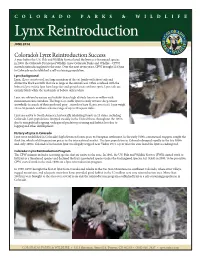

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Lynx Reintroduction JUNE 2014 Colorado’s Lynx Reintroduction Success A year before the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the lynx as a threatened species in 2000, the Colorado Division of Wildlife (now Colorado Parks and Wildlife - CPW) started reintroducing lynx to the state. Over the next seven years, CPW brought 218 lynx to Colorado and established a self-sustaining population. Lynx Background Lynx, (Lynx canadensis), are large members of the cat family with short tails and distinctive black ear tufts that are as large as the animal’s ear. Often confused with the bobcat (Lynx rufus), lynx have large feet and grayish coats without spots. Lynx tails are entirely black while the underside of bobcat tails is white. Lynx are solitary by nature and inhabit dense high altitude forests or willow-rich mountain stream corridors. The huge feet enable lynx to easily traverse deep winter snowfields in search of their preferred prey - snowshoe hare (Lepus americas). Lynx weigh 20-to-30 pounds and have a home range of up to 20 square miles Lynx are native to North America, historically inhabiting forests in 25 states, including Colorado. Lynx populations dropped steadily in the United States throughout the 1900s due to unregulated trapping, widespread predator poisoning and habitat loss due to logging and other development. History of Lynx in Colorado Lynx were established in Colorado’s high elevation forests prior to European settlement. In the early 1800s, commercial trappers sought the thick fur, which sold for premium prices in the international market. The lynx population in Colorado dropped rapidly in the late 1800s and early 1900s. -

Status and Conservation of the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx) in Europe in 2001

KORA Bericht Nr. 19 e Juni 2004 ISSN 1422-5123 Status and conservation of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe in 2001 Koordinierte Forschungsprojekte zur Erhaltung und zum Management der Raubtiere in der Schweiz. Coordinated research projects for the conservation and management of carnivores in Switzerland. KORA Projets de recherches coordonnés pour la conservation et la gestion des carnivores en Suisse. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, CH-3074 Muri. Tel +41-31-951 70 40, Fax +41-31-951 90 40, Email: [email protected], http://www.kora.unibe.ch Lynx Survey Europe 2001 2 KORA Bericht Nr. 19 englisch: Status and conservation of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe in 2001 Bearbeitung Manuela von Arx, Christine Breitenmoser- Adaptation Würsten, Fridolin Zimmermann and Editorship Urs Breitenmoser Bezugsquelle KORA, Thunstrasse 31, CH-3074 Muri Source T +41 31 951 70 40 / F +41 31 951 90 40 Source [email protected] Titelzeichnung Jacques Rime Frontispiece Cover drawing Online Version ELOIS (Eurasian Lynx Online Information System for Europe): http://www.kora.unibe.ch/en/proj/elois/online/index.html The report is also available on CD-Rom at KORA (details see above). Anzahl Seiten/Pages: 330 ISSN 1422-5123 © KORA Juni 2004 Lynx Survey Europe 2001 3 Status and conservation of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) in Europe in 2001 Edited by: Manuela von Arx, Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten, Fridolin Zimmermann, Urs Breitenmoser With the contribution of (in alphabetic order): Zanete Andersone, Henrik Andrén, Dragan Angelovski, Linas Balciauskas, Andriy-Taras Bashta, Ferdinand Bego, Urs Breitenmoser, Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten, Henrik Brøseth, Ludek Bufka, Marco Catello, Jaroslav Cerveny, Igor Dyky, Thomas Engleder, Michael Fasel, Martin Forstner, Christian Fuxjäger, Peter Genov, Constantinos Godes, Tomislav Gomercic, Eva Gregorova, Gennady Grishanov, Pavel Hell, Ulf Hohmann, Miso Hristovski, Djuro Huber, Thomas Huber, Ditmar Huckschlag, Ovidiu Ionescu, Thomas A.M.