The Beginning of the Viking Age in the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual

780S Series Spray Valves VALVEMATE™ 7040 Controller Operating Manual ® A NORDSON COMPANY US: 888-333-0311 UK: 0800 585733 Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 If you require any assistance or have spe- cific questions, please contact us. US: 888-333-0311 Telephone: 401-434-1680 Fax: 401-431-0237 E-mail: [email protected] Mexico: 001-800-556-3484 UK: 0800 585733 EFD Inc. 977 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914-1342 USA Sales and service of EFD Dispense Valve Systems is available through EFD authorized distributors in over 30 countries. Please contact EFD U.S.A. for specific names and addresses. Contents Introduction ..................................................................2 Specifications ..............................................................3 How The Valve and Controller Operate ......................4 Controller Operating Features ....................................5 Typical Setup ..............................................................6 Setup ........................................................................7-8 Adjusting the Spray......................................................9 Programming Nozzle Air Delay ..................................10 Spray Patterns ..........................................................11 Troubleshooting Guide ........................................12-13 Valve Maintenance................................................14-16 780S Exploded View..................................................17 Input / Output Connections..................................18-19 Connecting -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Wulfstan's Voyage the Baltic Sea Region in the Early Viking Age As Seen from Shipboard

MARITIME CULTURE OF THE NORTH ° 2 Wulfstan's Voyage The Baltic Sea region in the early Viking Age as seen from shipboard Edited by Anton Englert & Athena Trakadas Roskilde 2009 Contents Foreword • 7 by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen & Friedrich Liith I. WULFSTAN'S ACCOUNT Wulfstan's voyage and his description oiEstland: the text and the language of the text • 14 by Janet Bately Who was Wulfstan? • 29 by Judith Jesch Wulfstan's account in the context of early medieval travel literature • 57 by Rudolf Simek On the reliability of Wulfstan's report • 43 by Przemysiaw Urbanczyk II. THE WESTERN AND CENTRAL BALTIC SEA REGION IN THE 9™ AND 10™ CENTURIES Ests, Slavs and Saxons: ethnic groups and political structures • 50 by Christian Lu'bke, with a note by Przemysiaw Urbanczyk Danes and Swedes in written and archaeological sources at the end of the 9th century • §8 by Wladyslaw Duczko Routes and long-distance traffic — the nodal points of Wulfstan's voyage • 72 by Soren M. Sindbak Hedeby in Wulfstan's days: a Danish emporium of the Viking Age between East and West • 79 by Volker Hilberg Wulfstan and the coast of southern Scandinavia: sailing routes from Langeland to More - • 114 by Jo ban Callmer —r— -•- - Viking-Age sailing routes of the western Baltic Sea — a matter of safety • ZJJ by Jens Ulriksen Harbours and trading centres on Bornholm, Oland and Gotland in the late 9* century • 145 by Anne Norgard Jorgensen Ports and emporia of the southern coast: from Hedeby to Usedom and Wolin • 160 by Hauke Jons The settlement of Truso • 182 by Marek F. -

Introduction to 800 and Table 3

Introduction to 800 and Table 3 Version 1.3 December 2013 Learning Objectives The learner will: • Be familiar with the overall structure of the 800s • Be familiar with aids for building numbers in the 800s • Be familiar with circumstances in which Tables 3A, 3B, and 3C are used • Be able to build correct 800 numbers that use Tables 3A, 3B, and/or 3C • Be familiar with provisions for folk literature at 398.2 800 Literature: Scope In 800: • Literary texts • Works about literature • Anonymous classics Elsewhere: • Folk literature classed in 398.2 • Literature combined with other arts classed in 700, e.g., opera 782.1 800 Literature: Structure (1) 801-807 Standard subdivisions 808 Rhetoric (808.02-808.06 General topics in rhetoric; 808.1-808.7 Rhetoric in specific literary forms; comprehensive works in 808) 808.8 Collections of literary texts from more than two literatures 809 History, description, critical appraisal of more than two literatures 800 Literature: Structure (2) 810-890 Literatures of specific languages and language families 810 American literature in English 820-890 Follows pattern of Table 6 Languages (approximately) Aids to Number Building in 800 Literature Read the instructions in 800 schedule and at the beginning of Tables 3A and 3B Review extensive Manual notes for Table 3A-C and 800 Consult flow charts for Table 3A and 3B Consult Table of Mappings: DDC 000-990 to Table 3C—3 Arts and literature dealing with specific themes and subjects Table 3A Table 3A. Subdivisions for Works by or about Individual Authors Table 3A —1 -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

Situne Dei Årsskrift För Sigtunaforskning Och Historisk Arkeologi

Situne Dei Årsskrift för Sigtunaforskning och historisk arkeologi 2018 Redaktion: Anders Söderberg Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson Anna Kjellström Magnus Källström Cecilia Ljung Johan Runer Utgiven av Sigtuna Museum SITUNE DEI 2018 Viking traces – artistic tradition of the Viking Age in applied art of pre-Mongolian Novgorod Nadezhda N. Tochilova The Novgorod archaeological collection of wooden items includes a significant amount of pieces of decorative art. Many of these were featured in the fundamental work of B.A. Kolchin Novgorod Antiquities. The Carved Wood (Kolchin 1971). This work is, perhaps, the one generalizing study capable of providing a full picture of the art of carved wood of Ancient Novgorod. Studying the archaeological collec- tions of Ancient Novgorod, one’s attention is drawn to a number of wooden (and bone) objects, the art design of which distinctly differs from the general conceptions of ancient Russian art. The most striking examples of such works of applied art will be discussed in this article. The processes of interaction between the two cultures are well researched and presented in the works of a group of Swedish archaeologists, whose work showed the complex bonds of interaction between Sweden and Russia, reflected in a number of aspects of material culture (Arbman 1960; Jansson 1996; Fransson et al (eds.) 2007; Hedenstierna- Jonson 2009). Moreover, in art history literature, a few individ- ual works of applied art refer to the context of the spread of Viking art (Roesdahl & Wilson eds 1992; Graham-Campbell 2013), but not to the interrelation, as a definite branch of Scandinavian art, in Eastern Europe. If we apply this focus to Russian historiography, then the problem of studying archaeological objects of applied art is comparatively small, and what is important to note is that all of these studies also have an archaeological direction (Kolchin 1971; Bocharov 1983). -

Charlemagne's Heir

Charlemagne's Heir New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious (814-840) EDITED BY PETER' GOD MAN AND ROGER COLLINS CLARENDON PRESS . OXFORD 1990 5 Bonds of Power and Bonds of Association in the Court Circle of Louis the Pious STUART AIRLIE I TAKE my text from Thegan, from the well-known moment in his Life of Louis the Pious when the exasperated chorepiscopus of Trier rounds upon the wretched Ebbo, archbishop of Reims: 'The king made you free, not noble, since that would be impossible." I am not concerned with what Thegan's text tells us about concepts of nobility in the Carolingian world. That question has already been well handled by many other scholars, including JaneMartindale and Hans-Werner Goetz.! Rather, I intend to consider what Thegan's text, and others like it, can tell us about power in the reign of Louis the Pious. For while Ebbo remained, in Thegan's eyes, unable to transcend his origins, a fact that his treacherous behaviour clearly demonstrated, politically (and cultur- ally, one might add) Ebbo towered above his acid-tongued opponent. He was enabled to do this through his possession of the archbishopric of Reims and he had gained this through the largess of Louis the Pious. If neither Louis nor Charlemagne, who had freed Ebbo, could make him noble they could, thanks to the resources of patronage at their disposal, make him powerful, one of the potentes. It was this mis-use, as he saw it, of royal patronage that worried Thegan and it worried him because he thought that the rise of Ebbo was not a unique case. -

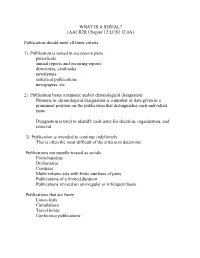

WHAT IS a SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A)

WHAT IS A SERIAL? (AACR2R Chapter 12/LCRI 12.0A) Publication should meet all three criteria 1) Publication is issued in successive parts periodicals annual reports and recurring reports directories, yearbooks newsletters statistical publications newspapers, etc. 2) Publication bears a numeric and/or chronological designation Numeric or chronological designation is a number or date given in a prominent position on the publication that distinguishes each individual issue Designation is used to identify each issue for check-in, organization, and retrieval 3) Publication is intended to continue indefinitely This is often the most difficult of the criteria to determine Publications not usually treated as serials Encyclopedias Dictionaries Censuses Multi-volume sets with finite numbers of parts Publications of a limited duration Publications revised on an irregular or infrequent basis Publications that are fuzzy Loose-leafs Cumulations Travel books Conference publications KEY POINTS OF SERIALS CATALOGING Base description on first or earliest issue. Every serial record should have a 362 or a 500 Description based on note. New record is created each time the title proper or corporate body (if main entry) changes. (See Serial title changes that require a new record) Cataloging record must represent the entire serial. Bib record must be general enough to apply to the entire serial, but specific enough to cover all access points. Notes are used to show changes in place of publication, publisher, issuing body, frequency, etc. Serial records should never have ISBN numbers for separate issues. Every serial should have a unique title. This is often accomplished with uniform titles. (See Uniform titles) Most serials do not have personal authors. -

Symbols of Power in Ireland and Scotland, 8Th-10Th Century Dr

Symbols of power in Ireland and Scotland, 8th-10th century Dr. Katherine Forsyth (Department of Celtic, University of Glasgow, Scotland) Prof. Stephen T. Driscoll (Department of Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Scotland) d Territorio, Sociedad y Poder, Anejo Nº 2, 2009 [pp. 31-66] TSP Anexto 4.indb 31 15/11/09 17:22:04 Resumen: Este artículo investiga algunos de los símbolos utilizaron las cruces de piedra en su inserción espacial como del poder utilizados por las autoridades reales en Escocia signos de poder. La segunda parte del trabajo analiza más e Irlanda a lo largo de los siglos viii al x. La primera parte ampliamente los aspectos visibles del poder y la naturaleza del trabajo se centra en las cruces de piedra, tanto las cruces de las sedes reales en Escocia e Irlanda. Los ejemplos exentas (las high crosses) del mundo gaélico de Irlanda estudiados son la sede de la alta realeza irlandesa en Tara y y la Escocia occidental, como las lastras rectangulares la residencia regia gaélica de Dunnadd en Argyll. El trabajo con cruz de la tierra de los pictos. El monasterio de concluye volviendo al punto de partida con el examen del Clonmacnoise ofrece un ejemplo muy bien documentado centro regio picto de Forteviot. de patronazgo regio, al contrario que el ejemplo escocés de Portmahomack, carente de base documental histórica, Palabras clave: pictos, gaélicos, escultura, Clonmacnoise, pero en ambos casos es posible examinar cómo los reyes Portmahomack, Tara, Dunnadd, Forteviot. Abstract: This paper explores some of the symbols of power landscape context as an expression of power. -

Toro Irrigation Golf Catalogue 2003

for pagination only... do not use this page. Golf Irrigation 20032003 ProductProduct ReferenceReference GuideGuide TABLE OF CONTENTS Toro Sprinklers Conversion Assembly Cross Reference Charts..............................................2 800S Series...................................................................................................3-6 690 and 670 Series..........................................................................................7 650 Series ........................................................................................................8 730 Series ........................................................................................................9 750 Series ......................................................................................................10 760 Series ......................................................................................................11 780 Series ......................................................................................................12 720 Series ......................................................................................................13 720G Series..............................................................................................14-15 2001® Series...................................................................................................16 Toro Valves 220 Series Brass ............................................................................................18 210 Series Brass ............................................................................................19