Samuel Slater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of Slavery Resolution

A RESOLUTION CALLING UPON BROWN TO ATTEMPT TO IDENTIFY AND REPARATE THE DESCENDANTS OF SLAVES ENTANGLED WITH THE UNIVERSITY Author: Jason Carroll, UCS President Cosponsors: Jai’el Toussaint, Zanagee Artis, Samra Beyene, Ana Boyd, Renee White, Zane Ruzicka WHEREAS in 2003, Brown University President Ruth Simmons appointed a Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice charged to investigate and prepare a report about the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade; WHEREAS, the final report by the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, presented to President Simmons in October of 2006, found that: I. University Hall, Brown University’s oldest building, according to construction records, was built by enslaved workers (13)1; II. the school’s first president, Rev. James Manning, arrived in Rhode Island accompanied by a personal slave (12); III. “many of the assets that underwrote the University’s creation and growth derived, directly and indirectly, from slavery and the slave trade” (13); IV. the Brown family of Providence, the University’s namesakes, were slave owners (14); V. in 1736, James Brown sent the first ever slave ship to sail from Providence, the Mary, to Africa, which carried a cargo of enslaved Africans to the West Indies before returning to Rhode Island with slaves for the Brown family’s own use (15); VI. the Brown family actively participated in the purchasing and selling of captives individually and in small lots, usually in the context of provisioning voyages (15); VII. in 1759, Obadiah Brown, Nicholas Brown, and John Brown, along with a handful of smaller investors, dispatched another ship to Africa which trafficked enslaved Africans before being captured by the French (15) 1 All numbered references are to the 2006 Slavery and Justice report by the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Foreseeable Futures#7 Position Papers From

Navigating the Past: Brown University and the Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764-65 James T. Campbell Foreseeable Futures#7 Position Papers from Artists and Scholars in Public Life Dear Reader, I am honored to introduce Foreseeable Futures # 7, James Campbell’s Navigating the Past: Brown University and the Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764-65. Campbell was chair of Brown University’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, charged by President Ruth Simmons in 2003 to investigate the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. The narrative around which Campbell organizes the Committee’s findings here is the 1764 voyage of the slave ship Sally from Providence to West Africa, where Captain Esek Hopkins “acquired” 196 men, women, and children intended for sale as slaves in Rhode Island. The Sally was owned by the four Brown brothers, benefactors of the College of Rhode Island, which in 1804 was renamed Brown University in recognition of a substantial gift from one of the brothers’ sons. The Committee’s willingness to resurrect that sober history and more, to organize public events to reflect on that legacy, exemplifies what Chancellor Nancy Cantor of Syracuse University calls scholarship in action. The Committee also issued concrete recommendations regarding ways that Brown students, faculty, and staff can continue to respond to that legacy in the present. The recommendations arise from Brown’s identity as an educational institution, “for the history of American education,” writes Campbell, “is -

Early Industry and Inventions

1 Early Industry and Inventions MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES New machines and factories changed The industrial development that Samuel Slater interchangeable the way people lived and worked in began more than 200 years ago Industrial parts the late 1700s and early 1800s. continues today. Revolution Robert Fulton factory system Samuel F. B. Lowell mills Morse ONE AMERICAN’S STORY In 1789, the Englishman Samuel Slater sailed to the United States under a false name. It was illegal for textile workers like him to leave the country. Britain wanted no other nation to copy its new machines for making thread and cloth. But Slater was going to bring the secret to America. With the backing of investor Moses Brown, Slater built the first successful water-powered textile mill in America. You will learn in Section Samuel Slater’s mill was located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. 1 how the development of industries changed the ways Americans lived and worked. Free Enterprise and Factories Taking Notes Use your chart to The War of 1812 brought great economic changes to the United States. take notes about It sowed the seeds for an Industrial Revolution like the one begun in early industry and Britain during the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, inventions. factory machines replaced hand tools, and large-scale manufacturing Causes replaced farming as the main form of work. For example, before the Industrial Revolution, women spun thread and wove cloth at home using spinning wheels and hand looms. The invention of such machines as the spinning jenny and the power loom made it possible for unskilled work- ers to produce cloth. -

RHODE ISLAND M Edical J Ournal

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL FEEDING OVERVIEW OF HYPERBARIC CHILDREN IN MEDICINE CENTER AT KENT HONDURAS PAGE 13 PAGE 19 BUTLER CREATES ARONSON CHAIR PAGE 44 GOOGLE GLASS MAGAZINER: IN RIH ED FIXING HEALTH CARE PAGE 47 PAGE 45 APRIL 2014 VOLUME 97• NUMBER 4 ISSN 2327-2228 Some things have changed in 25 years. Some things have not. Since 1988, physicians have trusted us to understand their professional liability, property, and personal insurance needs. Working with multiple insurers allows us to offer you choice and the convenience of one-stop shopping. Call us. 800-559-6711 rims I B C RIMS-INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION Medical/Professional Liability Property/Casualty Life/Health/Disability RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 7 COMMENTARY An Up-Front Guide to Getting Promoted: Slow and Steady JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD By the Sweat of Your Brow STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 41 RIMS NEWS CME: Eleventh Hour Education Event RIMS at the AMA National Advocacy Conference Why You Should Join RIMS 54 SPOTLIGHT Jordan Sack, MD’14: His early struggles with deafness and those who inspired him to help others 61 Physician’s LEXICON The Manifold Directions of Medicine STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 63 HERITAGE Timeless Advice to Doctors: You Must Relax MARY KORR RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL IN THE NEWS BUTLER HOSPITAL 44 51 JAMES F. PADBURY, MD creates Aronson Chair for receives March of Dimes Neurodegenerative research grant Disorders 52 BRENNA ANDERSON, MD IRA MAGAZINER 45 studies Group A strep on how to fix health care in pregnancy LIFESPAN 47 creates Clinical 52 SAMUEL C. -

Rhode Island Slavery and the University Jennifer Betts, University Archivist, Brown University Society of American Archivists, NOLA 2013

Rhode Island Slavery and the University Jennifer Betts, University Archivist, Brown University Society of American Archivists, NOLA 2013 Pre-Slavery and Justice Committee March 2001 David Horowitz’s “Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Slavery is a Bad Idea and Racist Too” July 2001 President Ruth Simmons sworn in 2002 Lawsuit against corporations mentioned Harvard, Yale, and Brown benefitted from slavery March 2004 Unearthing the past: Brown University, the Brown Family, and the Rhode Island Slave Trade symposium April 2004 “Slavery and justice: We seek to discover the meaning of our past” op ed Charge to the committee Members: 11 faculty 1 graduate student 2 administrators 3 undergraduate students Goal and charge: • Provide factual information and critical perspectives that will deepen understanding. • Organize academic events and activities that might help the nation and the Brown community think deeply, seriously, and rigorously about the questions raised by this controversy. Rhode Island and Slavery • Between 1725 and 1807 more than 900 ships from Rhode Island travelled to West Africa • Ships owned by Rhode Island merchants accounted for 60% of slave trade voyages in 18th and early 19th century • Rhode Island ships transported 106,000 slaves Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, Nicholas Brown, Sr. (1729-1791) Jr. (1769–1841) James Brown (1698-1739) Joseph Brown (1733-1785) (brothers) John Brown (1736-1803) Obadiah Brown (1712-1762) Moses Brown (1738-1836) Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, Nicholas Brown, Sr. (1729-1791) Jr. (1769–1841) James Brown • First record of slave (1698-1739) Joseph Brown trading in 1736 (1733-1785) • Mary left for Africa (brothers) • Obadiah sold slaves in John Brown West Indies (1736-1803) • Three slaves sold in Obadiah Brown Providence by James for (1712-1762) Moses Brown 120 pounds (1738-1836) Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, • SallyNicholas, 1764- 65:Brown, 109 of Sr. -

A Hous Widow

Robert l? Emlen A Hous f 0 r Widow row Architectural Statement and Social Position in Providence, 1791 Builtfor an artisan and shopkeepet;the interior of the Set-itDodge house was embellishedto a high standardfor the widow of one of Providences’ leading merchants. n the middle of picturesque rate, large-scale detailing in a middling Thomas Street, on College Hill in Providence residence and illustrates the Providence, Rhode Island, stands way in which architecture was used as a a house built about 1786 by the statement of social distinction by the lead- silversmith Seril Dodge (1759- ing family of postwar Providence. 1802)I (fig. 1). While typical in size of Seril Dodge chose to build his many wood-frame houses built in house next to the new meetinghouse of Providence in the last two decades of the the Charitable Baptist Society, built in eighteenth century, the Seril Dodge house 1774-75 on land occupied by the descen- is unique among these modest structures dants of Thomas Angell. The lane that in the elegance and extraordinary detail of passed through the Angel1 descendants ’ its interior finish work Although it has home lots, just north of the property they attracted the notice of architectural histo- sold to the Baptists, was originally known rians since at least 1934, when it was one as Angells’ Lane. In the nineteenth cen- of the first buildings in Rhode Island to be tury it became the town road known as recorded by the federal Historical Angel1 Street, with the exception of the American Buildings Survey, no explana- first block which, through a misreading of tion has been offered as to why such an the legend on a survey, was named ordinary house should boast such extraor- Thomas Street.1 dinary interiors. -

The Brown Papers the Record of a Rhode Island Business Family

The Brown Papers The Record of a Rhode Island Business Family BY JAMES B. HEDGES HE Brown Papers in the John Carter Brown Library T of Brown University constitute the major portion of the documents accumulated by the various members of the Brown family, of Providence, in the course of their multi- farious business activities during the period from 1726 to 1913.1 They comprise letters, ships' papers, invoices, ledgers, day books, log books, etc., and total approximately 350,000 separate pieces, of which by far the greater part consists of the letters which passed between the Browns and their correspondents scattered throughout those portions of the world where trade and business were transacted. About one- fifth of the collection relates to the period before 1783. Apart from the numerous specific dark corners of Ameri- can history on which they throw light, these papers are significant: first, because the Brown family touched so many difFerent facets of American business life; second, because of the family habit of destroying nothing that was important; this resulted in an initial completeness of the collection which no subsequent, self-appointed guardian of the family's reputation has seen fit to impair. The papers, therefore, give the plain, unvarnished version of several important chapters in the history of American business. They are notable in the third place because of their time span. There are, of course, many collections of papers ' A collection of Brown Papers, especially of Moses Brown, is in the Library of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence. 22 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY lApril, covering one or two generations of a given family or business but it is doubtful if there is another large body of documents in America representing seven generations of one business family, whose dominant business interests shifted from one generation to another. -

Joseph Brown, Astronomer by Stuart F. Crump, Jr. Rhode Island History

Joseph Brown, Astronomer by Stuart F. Crump, Jr. Rhode Island History, January 1968, 27:1, pp1-12 Digitally represented from original .pdf file presented on-line courtesy of the RI Historical Society at http://www.rihs.org/assetts/files/publications/1968_Jan.pdf DOCTOR J. WALTER WILSON has noted that all of the faculty at Brown University before 1790, with the exception of President Manning, were science professors. These men were David Howell, Joseph Brown, Benjamin Waterhouse, Benjamin West, and Perez Fobes. No doubt. Joseph Brown had much to do with establishing this trend.[1] Born on December 3, 1733, Joseph Brown was the son of James Brown and Hope (Power) Brown, and second oldest of the four Brown brothers, "Nick and Joe and John and Moe." His father, a merchant in Providence, died when Joseph was five, and the boy was brought up by his mother. It is interesting to note that he was a "consistent member of the Baptist Church, being the only one of the brothers who ever made a public profession of religion." [2] A testimonial to him written shortly after his death reads: "His Skill and Industry, in the earlier part of Life, in the Merchandize and Manufactures in which he was concerned, had rendered his Circumstances easy, if not affluent, and enabled him to indulge his natural Taste for Science." [3] Yet Joseph apparently had less interest in business than did his three brothers, and he spent a great deal of his time in intellectual pursuit. Professor Hedges points out that none of his business letters has survived, if indeed he ever wrote any.[4] His mind tended more toward science and mechanics than to trade and commerce. -

Moses Brown School Preferred Name *

;.. ‘‘ tates Department of the Interior :* _..ag’e Conservation and Recreation Service Q,HCRS -National Register of Historic Places dat. enterS Inventory-Nomination Form - See instructions In How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Friends’ Yearly Me eting School and/orcommon Moses Brown School preferred name * . 2. Location . street & number 250 Lloyd Avenue - not for publication city, town Providence - vicinity of congressional district112 Hon. Edward P. Beard state Rhode Islandeode 44 county Providence code 007 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use - district - public & occupied agriculture - museum ....._X buildings private unoccupied commercial - park structure both Iwork in progress .x. educational private residence - site Public Acquisition Accessible - entertainment - religious - object - In process ç yes: restricted - government - scientific being considered yes: unrest!icted - industrial - - transportation - no . military .. other: 4. Owner of Property name New England Yearly Meeting of Friends street&number The Maine Idyll U.S. Rte. 1 city, town R. D. 1, Freeport - vicinity of state Ma i tie 04032 5. Location of Legal Description . courthouse, registry ot deeds, etc. Providence City hail street & number 25 Dorrance Street Providence city, town state Rhode Island 02903 : 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Friends’ School, now Moses Brown School ;lfistorical American title Survey HABS #RI-255 has this property been determined eiegible? __yes date 1 963 .x_fede ral state county - local depository for survey records Rhode Island Historical Society Library ‘ city, town Providence state Rhode Tslarmd 02906 r’r’ 1: 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent _deteriorated .. unaltered JL original site _.2 good -. -

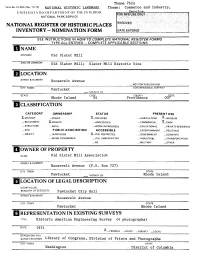

Iowner of Property

Theme 7b2a Form NO. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Theme: Commerce and Industry, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Old Slater Mill AND/OR COMMON Old Slater Mill; Slater Mill Historic Site LOCATION STREET* NUMBER RoO sevelt Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN Pawtucket CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF STATE n CO.UNTY ««QP DE Rhode Island nE4 Providence 007 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.D I STRICT —PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH. —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X—YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old Slater Mill Association STREET & NUMBER Roosevelt Avenue (P.O. Box 727) CITY. TOWN STATE Pawtucket VICINITY OF Rhode Island LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Pawtucket City Hall STREET & NUMBER Roosevelt Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Pawtucket Rhode Island REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Engineering Survey (4 photographs) DATE 1971 X — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and -

School Profile 2019-20

Moses Brown School 250 Lloyd Avenue, Providence, RI 02906-2398 2019-20 profile P: (401) 831-7350 F: (401) 455-0084 Mosesbrown.org School CEEB Code: 400180 Matt Glendinning, Ph.D. OUR PHILOSOPHY Consistent with our Quaker school philosophy, the college counseling offce seeks to nurture the Inner Light of students through the college process. Head of School We encourage young people to refect deeply about their values and priorities as well as their talents and gifts in order to identify institutions that best match their personal, educational and professional Debora Phipps goals. Whether our students choose to enroll in one of the nation’s leading liberal arts colleges, public ASSISTANT HEAD OF fagship institutions or premier research universities, they are well prepared to let their lives speak as SCHOOL: ACADEMICS they lead in the 21st century. The college options for Moses Brown graduates are as broad and diverse as our students’ talents and interests. Elise London HEAD OF UPPER SCHOOL 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 Julia Baker ENROLLMENT CO-DIRECTOR 175 155 411 of college counseling 100 105 104 102 [email protected] LOWER MIDDLE UPPER SCHOOL SCHOOL SCHOOL GRADE 9 GRADE 10 GRADE 11 GRADE 12 34% of Upper School students receive Financial Assistance. 100% of graduating seniors will attend a 4-year college. Laurie J. Nelson 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 0.00800 106.25 212.50 318.75 425.00 CO-DIRECTOR of college counseling GRADE SYSTEM AND RANKING POLICY GRADING SCALE: [email protected] The Moses Brown school year consists of two semesters, each approximately eighteen A + = 4.3 weeks long.