Ingenious Machinists to British Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book the Industrial Revolution Set Ebook

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Grolier | 10 pages | 01 Mar 2005 | Grolier, Inc. | 9780717260317 | English | none The Industrial Revolution Set PDF Book This AI, in turn, liaises with your home hub chatbot facility which rebukes you and suggests you cut down on fats and make more use of your home gym subscription and, if deemed necessary, sets up a home visit or virtual reality appointment with your local nurse or doctor. Compare Accounts. However there were two challenges due to which Britain did not grow cotton: its cold climate ; and not enough manpower to meet the demand. The United States government helped businesses by instituting tariffs—taxes on foreign goods—so that products like steel made by U. Key Takeaways The American Industrial Revolution commonly referred to as the second Industrial Revolution, started sometime between and The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were filled with examples of social and economic struggle. He was cheated out of his invention by a group of manufacturers who paid him much less than they had promised for the design. They can be used for classwork, homework, research or as a platform for projects. Macroeconomics Is Industrialization Good for the Economy? This then ushered the factory system , which was key to the Industrial Revolution. Physical products and services, moreover, can now be enhanced with digital capabilities that increase their value. But these think tanks and consultancies are hardly going to be held directly responsible for the future they help to produce. Partner Links. The Second used electric power to create mass production. In Italian physicist and inventor Guglielmo Marconi perfected a system of wireless telegraphy radiotelegraphy that had important military applications in the 20th century. -

Samuel Slater's Sunday School and the American Industrial Revolution

Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 4 Issue 1, June 2019 Pennell More than a ‘Curious Cultural Sideshow’: Samuel Slater's Sunday School and the Role of Literacy Sponsorship in Disciplining Labor Michael Pennell, University of Kentucky Abstract This article investigates the concept of literacy sponsorship through the introduction of textile factories and mill villages in New England during the American Industrial Revolution. Specifically, the article focuses on Samuel Slater’s mill villages and his disciplining and socialization of workers via the ‘family’ approach to factory production, and, in particular, his support of the Sunday school. As an institution key to managerial control and new to rural New England, the Sunday school captures the complicated networks of moral and literacy sponsorship in the transition to factory production. Keywords Industrial revolution, textile mills, literacy sponsorship, Sunday school, Samuel Slater Describing the bucolic New England manufacturing scene of the early nineteenth century, Zachariah Allen (1982 p. 6) writes, ‘[A]long the glens and meadows of solitary watercourses, the sons and daughters of respectable farmers, who live in neighborhood of the works, find for a time a profitable employment.’ A textile manufacturer and pro-industry voice in America, Allen sought to distinguish the ‘little hamlets’ of New England from the factory cities of England in the early nineteenth century. Undoubtedly, one of those ‘small communities’ to which Allen refers is Samuel Slater’s mill village in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Unlike the factory system of England, or the factory city of Lowell, Massachusetts, to the north, Slater’s village approach cultivated a ‘new work order’ relying on families, specifically children, and villages, located along pastoral landscapes, such as the Blackstone River Valley in northern Rhode Island. -

The Industrial Revolution in America

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A SECTION 1 The Industrial TEKS 5B, 5D, 7A, 11A, 12C, 12D, 13A, Revolution in 13B, 14A, 14B, 27A, 27D, 28B What You Will Learn… America Main Ideas 1. The invention of new machines in Great Britain If YOU were there... led to the beginning of the You live in a small Pennsylvania town in the 1780s. Your father is a Industrial Revolution. 2. The development of new blacksmith, but you earn money for the family, too. You raise sheep machines and processes and spin their wool into yarn. Your sisters knit the yarn into warm brought the Industrial Revolu- tion to the United States. wool gloves and mittens. You sell your products to merchants in the 3. Despite a slow start in manu- city. But now you hear that someone has invented machines that facturing, the United States made rapid improvements can spin thread and make cloth. during the War of 1812. Would you still be able to earn the same amount The Big Idea of money for your family? Why? The Industrial Revolution trans- formed the way goods were produced in the United States. BUILDING BACKOU GR ND In the early 1700s making goods depend- ed on the hard work of humans and animals. It had been that way for Key Terms and People hundreds of years. Then new technology brought a change so radical Industrial Revolution, p. 385 that it is called a revolution. It began in Great Britain and soon spread to textiles, p. -

Descendants of Slavery Resolution

A RESOLUTION CALLING UPON BROWN TO ATTEMPT TO IDENTIFY AND REPARATE THE DESCENDANTS OF SLAVES ENTANGLED WITH THE UNIVERSITY Author: Jason Carroll, UCS President Cosponsors: Jai’el Toussaint, Zanagee Artis, Samra Beyene, Ana Boyd, Renee White, Zane Ruzicka WHEREAS in 2003, Brown University President Ruth Simmons appointed a Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice charged to investigate and prepare a report about the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade; WHEREAS, the final report by the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, presented to President Simmons in October of 2006, found that: I. University Hall, Brown University’s oldest building, according to construction records, was built by enslaved workers (13)1; II. the school’s first president, Rev. James Manning, arrived in Rhode Island accompanied by a personal slave (12); III. “many of the assets that underwrote the University’s creation and growth derived, directly and indirectly, from slavery and the slave trade” (13); IV. the Brown family of Providence, the University’s namesakes, were slave owners (14); V. in 1736, James Brown sent the first ever slave ship to sail from Providence, the Mary, to Africa, which carried a cargo of enslaved Africans to the West Indies before returning to Rhode Island with slaves for the Brown family’s own use (15); VI. the Brown family actively participated in the purchasing and selling of captives individually and in small lots, usually in the context of provisioning voyages (15); VII. in 1759, Obadiah Brown, Nicholas Brown, and John Brown, along with a handful of smaller investors, dispatched another ship to Africa which trafficked enslaved Africans before being captured by the French (15) 1 All numbered references are to the 2006 Slavery and Justice report by the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

Henry Cabot Lodge

1650 Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Lodges Main Political Affiliation: (of Massachusetts & Connecticut) 1763-83 1789-1823 Federalist ?? 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1700 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican 1750 Giles Lodge (1770-1852); (planter/merchant) (Emigrated from London, England to Santo Domingo, then Massachusetts, 1791) See Langdon of NH = Abigail Harris Langdon Genealogy (1776-1846) (possibly descended from John, son of John Langdon, 1608-97) 1800 10 Others John Ellerton Lodge (1807-62) (moved to New Orleans, 1824); (returned to Boston with fleet of merchant ships, 1835) (engaged in trade with China); (died in Washington state) See Cabot of MA = Anna Sophia Cabot Genealogy (1821-1901) Part I Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) 1850 (MA house, 1880); (ally of Teddy Roosevelt) See Davis of MA (US House, 1887-93); (US Senate, 1893-1924; opponent of League of Nations) Genealogy Part I = Ann Cabot Mills Davis (1851-1914) See Davis of MA Constance Davis George Cabot Lodge Genealogy John Ellerton Lodge Cabot Lodge (1873-1909) Part I (1878-1942) (1872-after 1823) = Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen Davis (1875-at least 1903) (Oriental art scholar) = Col. Augustus Peabody Gardner = Mary Connally (1885?-at least 1903) (1865-1918) Col. Henry Cabot Lodge Cmd. John Davis Lodge Helena Lodge 1900(MA senate, 1900-01) (from Canada) (US House, 1902-17) (1902-85); (Rep); (newspaper reporter) (1903-85); (Rep) (1905-at least 1970) (no children) (WWI/US Army) (MA house, 1933-36); (US Senate, 1937-44, 1947-53; (movie actor, 1930s-40s); -

Foreseeable Futures#7 Position Papers From

Navigating the Past: Brown University and the Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764-65 James T. Campbell Foreseeable Futures#7 Position Papers from Artists and Scholars in Public Life Dear Reader, I am honored to introduce Foreseeable Futures # 7, James Campbell’s Navigating the Past: Brown University and the Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764-65. Campbell was chair of Brown University’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, charged by President Ruth Simmons in 2003 to investigate the University’s historical relationship to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. The narrative around which Campbell organizes the Committee’s findings here is the 1764 voyage of the slave ship Sally from Providence to West Africa, where Captain Esek Hopkins “acquired” 196 men, women, and children intended for sale as slaves in Rhode Island. The Sally was owned by the four Brown brothers, benefactors of the College of Rhode Island, which in 1804 was renamed Brown University in recognition of a substantial gift from one of the brothers’ sons. The Committee’s willingness to resurrect that sober history and more, to organize public events to reflect on that legacy, exemplifies what Chancellor Nancy Cantor of Syracuse University calls scholarship in action. The Committee also issued concrete recommendations regarding ways that Brown students, faculty, and staff can continue to respond to that legacy in the present. The recommendations arise from Brown’s identity as an educational institution, “for the history of American education,” writes Campbell, “is -

Early Industry and Inventions

1 Early Industry and Inventions MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES New machines and factories changed The industrial development that Samuel Slater interchangeable the way people lived and worked in began more than 200 years ago Industrial parts the late 1700s and early 1800s. continues today. Revolution Robert Fulton factory system Samuel F. B. Lowell mills Morse ONE AMERICAN’S STORY In 1789, the Englishman Samuel Slater sailed to the United States under a false name. It was illegal for textile workers like him to leave the country. Britain wanted no other nation to copy its new machines for making thread and cloth. But Slater was going to bring the secret to America. With the backing of investor Moses Brown, Slater built the first successful water-powered textile mill in America. You will learn in Section Samuel Slater’s mill was located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. 1 how the development of industries changed the ways Americans lived and worked. Free Enterprise and Factories Taking Notes Use your chart to The War of 1812 brought great economic changes to the United States. take notes about It sowed the seeds for an Industrial Revolution like the one begun in early industry and Britain during the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, inventions. factory machines replaced hand tools, and large-scale manufacturing Causes replaced farming as the main form of work. For example, before the Industrial Revolution, women spun thread and wove cloth at home using spinning wheels and hand looms. The invention of such machines as the spinning jenny and the power loom made it possible for unskilled work- ers to produce cloth. -

RHODE ISLAND M Edical J Ournal

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL FEEDING OVERVIEW OF HYPERBARIC CHILDREN IN MEDICINE CENTER AT KENT HONDURAS PAGE 13 PAGE 19 BUTLER CREATES ARONSON CHAIR PAGE 44 GOOGLE GLASS MAGAZINER: IN RIH ED FIXING HEALTH CARE PAGE 47 PAGE 45 APRIL 2014 VOLUME 97• NUMBER 4 ISSN 2327-2228 Some things have changed in 25 years. Some things have not. Since 1988, physicians have trusted us to understand their professional liability, property, and personal insurance needs. Working with multiple insurers allows us to offer you choice and the convenience of one-stop shopping. Call us. 800-559-6711 rims I B C RIMS-INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION Medical/Professional Liability Property/Casualty Life/Health/Disability RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 7 COMMENTARY An Up-Front Guide to Getting Promoted: Slow and Steady JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD By the Sweat of Your Brow STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 41 RIMS NEWS CME: Eleventh Hour Education Event RIMS at the AMA National Advocacy Conference Why You Should Join RIMS 54 SPOTLIGHT Jordan Sack, MD’14: His early struggles with deafness and those who inspired him to help others 61 Physician’s LEXICON The Manifold Directions of Medicine STANLEY M. ARONSON, MD 63 HERITAGE Timeless Advice to Doctors: You Must Relax MARY KORR RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL IN THE NEWS BUTLER HOSPITAL 44 51 JAMES F. PADBURY, MD creates Aronson Chair for receives March of Dimes Neurodegenerative research grant Disorders 52 BRENNA ANDERSON, MD IRA MAGAZINER 45 studies Group A strep on how to fix health care in pregnancy LIFESPAN 47 creates Clinical 52 SAMUEL C. -

Hclassification

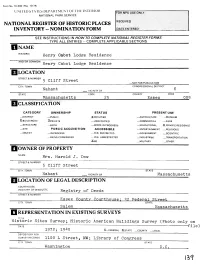

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Rhode Island Slavery and the University Jennifer Betts, University Archivist, Brown University Society of American Archivists, NOLA 2013

Rhode Island Slavery and the University Jennifer Betts, University Archivist, Brown University Society of American Archivists, NOLA 2013 Pre-Slavery and Justice Committee March 2001 David Horowitz’s “Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Slavery is a Bad Idea and Racist Too” July 2001 President Ruth Simmons sworn in 2002 Lawsuit against corporations mentioned Harvard, Yale, and Brown benefitted from slavery March 2004 Unearthing the past: Brown University, the Brown Family, and the Rhode Island Slave Trade symposium April 2004 “Slavery and justice: We seek to discover the meaning of our past” op ed Charge to the committee Members: 11 faculty 1 graduate student 2 administrators 3 undergraduate students Goal and charge: • Provide factual information and critical perspectives that will deepen understanding. • Organize academic events and activities that might help the nation and the Brown community think deeply, seriously, and rigorously about the questions raised by this controversy. Rhode Island and Slavery • Between 1725 and 1807 more than 900 ships from Rhode Island travelled to West Africa • Ships owned by Rhode Island merchants accounted for 60% of slave trade voyages in 18th and early 19th century • Rhode Island ships transported 106,000 slaves Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, Nicholas Brown, Sr. (1729-1791) Jr. (1769–1841) James Brown (1698-1739) Joseph Brown (1733-1785) (brothers) John Brown (1736-1803) Obadiah Brown (1712-1762) Moses Brown (1738-1836) Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, Nicholas Brown, Sr. (1729-1791) Jr. (1769–1841) James Brown • First record of slave (1698-1739) Joseph Brown trading in 1736 (1733-1785) • Mary left for Africa (brothers) • Obadiah sold slaves in John Brown West Indies (1736-1803) • Three slaves sold in Obadiah Brown Providence by James for (1712-1762) Moses Brown 120 pounds (1738-1836) Brown Family Tree Nicholas Brown, • SallyNicholas, 1764- 65:Brown, 109 of Sr.