Samuel Slater's Sunday School and the American Industrial Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book the Industrial Revolution Set Ebook

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Grolier | 10 pages | 01 Mar 2005 | Grolier, Inc. | 9780717260317 | English | none The Industrial Revolution Set PDF Book This AI, in turn, liaises with your home hub chatbot facility which rebukes you and suggests you cut down on fats and make more use of your home gym subscription and, if deemed necessary, sets up a home visit or virtual reality appointment with your local nurse or doctor. Compare Accounts. However there were two challenges due to which Britain did not grow cotton: its cold climate ; and not enough manpower to meet the demand. The United States government helped businesses by instituting tariffs—taxes on foreign goods—so that products like steel made by U. Key Takeaways The American Industrial Revolution commonly referred to as the second Industrial Revolution, started sometime between and The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were filled with examples of social and economic struggle. He was cheated out of his invention by a group of manufacturers who paid him much less than they had promised for the design. They can be used for classwork, homework, research or as a platform for projects. Macroeconomics Is Industrialization Good for the Economy? This then ushered the factory system , which was key to the Industrial Revolution. Physical products and services, moreover, can now be enhanced with digital capabilities that increase their value. But these think tanks and consultancies are hardly going to be held directly responsible for the future they help to produce. Partner Links. The Second used electric power to create mass production. In Italian physicist and inventor Guglielmo Marconi perfected a system of wireless telegraphy radiotelegraphy that had important military applications in the 20th century. -

The Industrial Revolution in America

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A SECTION 1 The Industrial TEKS 5B, 5D, 7A, 11A, 12C, 12D, 13A, Revolution in 13B, 14A, 14B, 27A, 27D, 28B What You Will Learn… America Main Ideas 1. The invention of new machines in Great Britain If YOU were there... led to the beginning of the You live in a small Pennsylvania town in the 1780s. Your father is a Industrial Revolution. 2. The development of new blacksmith, but you earn money for the family, too. You raise sheep machines and processes and spin their wool into yarn. Your sisters knit the yarn into warm brought the Industrial Revolu- tion to the United States. wool gloves and mittens. You sell your products to merchants in the 3. Despite a slow start in manu- city. But now you hear that someone has invented machines that facturing, the United States made rapid improvements can spin thread and make cloth. during the War of 1812. Would you still be able to earn the same amount The Big Idea of money for your family? Why? The Industrial Revolution trans- formed the way goods were produced in the United States. BUILDING BACKOU GR ND In the early 1700s making goods depend- ed on the hard work of humans and animals. It had been that way for Key Terms and People hundreds of years. Then new technology brought a change so radical Industrial Revolution, p. 385 that it is called a revolution. It began in Great Britain and soon spread to textiles, p. -

Early Industry and Inventions

1 Early Industry and Inventions MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES New machines and factories changed The industrial development that Samuel Slater interchangeable the way people lived and worked in began more than 200 years ago Industrial parts the late 1700s and early 1800s. continues today. Revolution Robert Fulton factory system Samuel F. B. Lowell mills Morse ONE AMERICAN’S STORY In 1789, the Englishman Samuel Slater sailed to the United States under a false name. It was illegal for textile workers like him to leave the country. Britain wanted no other nation to copy its new machines for making thread and cloth. But Slater was going to bring the secret to America. With the backing of investor Moses Brown, Slater built the first successful water-powered textile mill in America. You will learn in Section Samuel Slater’s mill was located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. 1 how the development of industries changed the ways Americans lived and worked. Free Enterprise and Factories Taking Notes Use your chart to The War of 1812 brought great economic changes to the United States. take notes about It sowed the seeds for an Industrial Revolution like the one begun in early industry and Britain during the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, inventions. factory machines replaced hand tools, and large-scale manufacturing Causes replaced farming as the main form of work. For example, before the Industrial Revolution, women spun thread and wove cloth at home using spinning wheels and hand looms. The invention of such machines as the spinning jenny and the power loom made it possible for unskilled work- ers to produce cloth. -

Samuel Slater and the Spinning Machine by Jane Runyon

Name Date Samuel Slater and the Spinning Machine By Jane Runyon Take a step back into history. Winter is coming in 1770, and your mother wants to make sure your clothing will keep you warm during the cold months. When you try on your best shirt, you find that you have grown right out of it. You must have a new shirt. Where do you go to find it? Do you go to the nearest mall? Do you have a choice of color and style? Of course you don't. Shopping was different in those days. Most towns had only one place to go for supplies. This shop was often called a mercantile. You could find anything from knives to seeds or flour to bonnets in this small store. Most of these supplies had been shipped to the colonies from Europe. British merchants bought the supplies in European countries and brought them to the colonies on their own ships. They sold the supplies to colonial merchants for a profit. The colonial merchant sold the goods to the colonists and made a small profit himself. All of these profits added to the cost of shipping the goods sometimes made the cost of the items hard to afford. To bring the cost down, many colonists decided to produce their own goods. Growing food and using natural resources, such as wood for carpentry items and ships, was fairly easy to do. One of the harder items to supply was cloth and textile products. Do you know how a shirt was made in those days? Let's see what it would take to make a cotton shirt. -

Industrial Revolution Industrial Revolution Begins in Britain

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION BEGINS IN BRITAIN Industrial Revolution—greatly increases output of machine-made goods Revolution begins in England in the middle 1700s Starts with agriculture- large, enclosed farms, wealthy landowners, leads to experimentation with farming methods and tools Crop rotation—switching crops each year to avoid depleting the soil Livestock breeders allow only the best to breed, improve food supply More meat and crops=Better nutrition=fewer go hungry INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION BEGINS IN BRITAIN Britain has natural resources—coal, iron, rivers, harbors Expanding economy in Britain encourages investment Britain has all needed factors of production— land, labor, capital Stable Banking System- most developed in all of Europe Loan money at reasonable interest rate More people able to borrow and invest in better machineries, build new factories, and expand their operations INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION Inventors discovered new ways of doing things to make life easier and to get things done faster Pre Industrial Revolution- everything made at home by hand After Industrial Revolution- goods manufactured in factories- buildings that house machines- such as the spinning jenny, power loom, water frames, steam engine, and later the cotton gin Urbanization- People moved from villages to cities to work in mines and textile factories Before IR, most people lived in small villages and worked hard 7 days a week from morning until night and still struggled to make a living FACTORY LIFE Work 12-14 hours a day; 6 days a week Poor working conditions- Dirty, poorly lit, and dangerous due to low ceilings and locked windows and doors. Paid low wages and would reduce wages if late, made a mistake, or business bad. -

Chapter 12 the North Chapter 13 the South Chapter 14 New Movements in America Chapter 15 a Divided Nation

UNIT 4 1790—1860 The Nation Expands Chapter 12 The North Chapter 13 The South Chapter 14 New Movements in America Chapter 15 A Divided Nation 378 6-8_SNLAESE484693_U04O.indd 378 7/2/10 1:06:42 PM What You Will Learn… The United States continued to grow in size and wealth, experiencing revolutions in technology and business as did other parts of the world. During the earliest phases of expansion, regions of the United States developed differently from each other. Citizens differed in their ideas of progress, government, and religion. For the success of the nation, they tried to compromise on their disagreements. In the next four chap- ters, you will learn about two regions in the United States, and how they were alike and different. Explore the Art This painting shows a bustling street scene in New York City around 1797. What does the scene indicate about business in the city during this period? 379 6-8_SNLAESE484693_U04O.indd 379 7/2/10 1:07:17 PM FLORIDA . The Story Continues CHAPTER 12, The North Expands (1790–1860) EVENTS 1851: The fi rst installment of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is printed. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote a ctional story intended to show the evils of slavery. e story, initially written and published in installments in a magazine, was so popular that Stowe decided to publish it in book form. e story had its intended e ect… rallying thousands of people in support of the anti-slavery movement. As popular as the story was in the North, it enraged slave supporters in Florida and across the South, and fueled the division between the North and the South that led to the outbreak of the Civil War. -

Sainuel Slater II Father of the American Industrial Revolution

; ; S Sainuel Slater II Father of the American Industrial Revolution Samuel Slater Son of a yeoman farmer, Samuel Slater was born in Belper. Derbyshire. England on June 9, 1768. He become involved in the textile industry at the age of 14 when he was apprenticed to Jedediah Strutt, a partner of Richard Arkwright and the owner of one of the first cotton mills in Belper. Slater worked for Strutt for eight years and rose to become superintendent of Strutt’s mill. It was in this capacity that he gained a comprehensive understanding of Arkwright’s machines. Believing that textile industry in England had reached its peak, Slater emigrated secretly to America in 1789 in hopes of making his fortune in Americ&s infant textile industry. While others with textile manufacturing experience had emigrated before him, Slater was the first who knew how to build as well as operate textile machines. Slater, with funding from Providence investors and assistance from skilled local artisans, built the first successful water powered textile mill in Pawtucket in 1793. Samuel Slater By the time other firms entered the industry, Slate?s organizational methods had become the model for his successors in the Blackstone River Valley. Later known as the Rhode Island System, it began when Slater enlisted entire families, including children, to work in his mills. These families often lived in company owned housing located near the mills, shopped at the company stores and attended company schools and churches. While not big enough to support the large mills which became common in Massachusetts, the Blackstone River’s steep drop and numerous falls provided ideal conditions for the development of small, rural textile mills around which mill villages developed. -

Iowner of Property

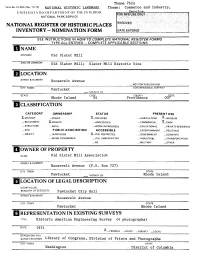

Theme 7b2a Form NO. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Theme: Commerce and Industry, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Old Slater Mill AND/OR COMMON Old Slater Mill; Slater Mill Historic Site LOCATION STREET* NUMBER RoO sevelt Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN Pawtucket CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF STATE n CO.UNTY ««QP DE Rhode Island nE4 Providence 007 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.D I STRICT —PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH. —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X—YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old Slater Mill Association STREET & NUMBER Roosevelt Avenue (P.O. Box 727) CITY. TOWN STATE Pawtucket VICINITY OF Rhode Island LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Pawtucket City Hall STREET & NUMBER Roosevelt Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Pawtucket Rhode Island REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Engineering Survey (4 photographs) DATE 1971 X — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and -

Textiles, Trenton, and a First Taste of the Industrial Revolution

On The Eagle’s Wings: Textiles, Trenton, and a First Taste of the Industrial Revolution Richard W. Hunter, Nadine Sergejeff and Damon Tvaryanas1 Abstract This paper relates the rise, fluctuating fortunes and eventual fall of the Eagle Factory, Trenton‟s first major textile manufacturing enterprise, located on the Assunpink Creek in the heart of New Jersey‟s capital city. Established in 1814 at the dawn of the American Industrial Revolution and controlled throughout by the Walns, a prominent Quaker merchant family of Philadelphia, the Eagle Factory began by producing yarns and hand-woven goods. Following the introduction of power looms in the 1820s the factory shifted into the mass production of a variety of machine-made fabrics, including plaids, checks, muslin, gingham, ticking and a number of more distinctive cloths. However, this strictly family-run enterprise was never entirely successful, falling victim to broader global economic forces and regional competition, as well as several floods and fires. The plant closed altogether following a devastating fire in 1845. In tracing the checkered history of the Eagle Factory, liberal use is made of the letter book of Lewis Waln and the Waln family papers at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as well as insurance records, newspaper advertisements and land records. Trenton‟s roots as an industrial city generally are traced to the manufacture of iron, steel and pottery, and to the entrepreneurial efforts of well-known individuals like Peter Cooper, Abram S. Hewitt, John A. Roebling, Thomas Maddock, John Hart Brewer and Walter Scott Lenox in the mid to late nineteenth century. -

Nber Working Paper Series Infrastructure and Urban

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INFRASTRUCTURE AND URBAN FORM Edward L. Glaeser Working Paper 28287 http://www.nber.org/papers/w28287 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2020 I am grateful to Margaret Brissenden and Eliza Glaeser for editorial assistance. Greg Ingram provided excellent comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2020 by Edward L. Glaeser. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Infrastructure and Urban Form Edward L. Glaeser NBER Working Paper No. 28287 December 2020 JEL No. F61,N70,R14,R41 ABSTRACT Cities are shaped by transportation infrastructure. Older cities were anchored by waterways. Nineteenth century cities followed the path of streetcars and subways. The 20th century city rebuilt itself around the car. The close connection between transportation and urban form is natural, since cities are defined by their density. Physical proximity and transportation investments serve the common cause of reducing the transportation costs for goods, people and ideas. The close connection between transportation and urban form suggests the need for spatial equilibrium models that embed a full set of equilibrium effects into any evaluation of transportation spending. Their connection implies that restrictions on land use will change, and often reduce, the value of investing in transportation infrastructure. -

The Industrial Revolution Help Shape Life in the North?

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-C Module 13 The North Essential Question How did the Industrial Revolution help shape life in the North? About the Photo: New machinery like In this module you will read about the changes that occurred in the lives this textile mill helped fuel the Industrial of Americans in the North as the result of rapid industrialization. You will Revolution. also learn about some of the new inventions of the period. What You Will Learn … Lesson 1: The Industrial Revolution in America . 424 Explore ONLINE! The Big Idea The Industrial Revolution transformed the way goods VIDEOS, including... were produced in the United States. • Industrial Revolution Lesson 2: Changes in Working Life . 430 The Big Idea The introduction of factories changed working life for • Train Technology many Americans. Lesson 3: The Transportation Revolution . 435 The Big Idea New forms of transportation improved business, travel, and communication in the United States. Lesson 4: More Technological Advances . 441 The Big Idea Advances in technology led to new inventions that Document-Based Investigations continued to change daily life and work. Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Image Carousel: Elements of Mass Production Image with Hotspots: Life of a Mill Girl Image with Hotspots: The Steam Train 420 Module 13 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 1785–1860 Explore ONLINE! United States World 1785 1790 The first steam-powered mill opens in Great Britain. 1800 1807 Robert Fulton’s Clermont becomes the first commercially successful steamboat. -

Discovering the Industrial Revolution in Killingly, CT Lesson

Discovering the Industrial Revolution in Killingly Connecticut TEACHING AMERICAN HISTORY PROJECT Lesson Title - Discovering the Industrial Revolution in Killingly, CT From Joseph Lewerk Grade – 9 - 12 Length of class period – 90 minutes Inquiry – (What essential question are students answering, what problem are they solving, or what decision are they making?) How is the birthplace of the American industrial revolution in Pawtucket, Rhode Island connected to the history of manufacturing in eastern Connecticut's town of Killingly? Objectives (What content and skills do you expect students to learn from this lesson?) Work with a group, compare and contrast industrialization in Pawtucket, Rhode Island and Killingly, Connecticut. Analyze why these similarities and differences exist. Write an essay that explains the similarities and differences and offer an explanation as to why the similarities and differences exist. Materials (What primary sources or local resources are the basis for this lesson?) – (please attach) 1. Slater Mill historical background materials and mill photos (appended below) 2. Miles of Millstreams, Section IV, The Age of Small Mills, Killingly Historical Society, 1976 (attachment) - Used with permission of Marilyn Labbe from the Killingly Historical Society on behalf of the authors: Margaret Weaver, Geraldine A. Wood and Raymond H. Wood. Activities (What will you and your students do during the lesson to promote learning?) 1. Students in small groups (3-4 homogeneously grouped) will brainstorm what they know about industrialization, especially any local connection. Ideas will then be shared by the class and recorded on the board by the teacher. 2. Working in the same small groups students will examine the materials in Handout 1 related to the industrialization effort started by Samuel Slater in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, constructing a timeline charting key developments beginning with Slater's time in England.