Coborosttfs-0-2,/Vjg the ROLE of CHRISTIAN ORGANISATIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Response to Portuguese Missionary Methods in India in the 16Th – 17Th Centuries

UNDERSTANDING THE RESPONSE TO PORTUGUESE MISSIONARY METHODS IN INDIA IN THE 16TH – 17TH CENTURIES Christianity has had a very long history in the sub-continent. Even if the traditional belief of the arrival of one of the apostles of Jesus, St. Thomas is discounted, there is evidence to prove that Christian merchants from west Asia had sailed and settled on the west coast of India in the early centuries of the present era. Catholic missionaries, mainly of the Franciscan order arrived as early as the 13th century, in the northern reaches of the Indian west coast. Some of them were, in medieval terminology, even “martyred” for the faith.1 The arrival of the Portuguese, with their padroado (patronage) privileges however marks the first large-scale appearance of Christian missionaries in India. Despite such a longstanding Christian tradition the focus of Church history writing in India, in the context of it being written as a form of ‘mission history’ has always been on the agency, the agents and their work. This has meant that the overarching emphasis has been on the mission bodies, their practices and when it has concentrated on the local bodies, the numbers they were able to convert. Conversion stories have also been narrated, yet it is done with the view to highlight the activities of the mission and their underlying role in bringing about that conversion. This overemphasis on the work of the converting agencies was no doubt the consequence of the need to legitimize their work as well as the need for further financial and other forms of aid, but it has had several implications. -

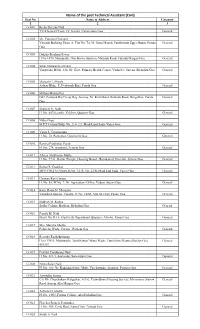

List of Representation /Objection Received Till 31St Aug 2020 W.R.T. Thomas & Araujo Committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No

List of Representation /Objection Received till 31st Aug 2020 w.r.t. Thomas & Araujo committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No. Sy.No. Penha de Leflor, H.no 223/7. BB Borkar Road Alto 1 Bardez Leo Remedios Mendes 9822121352 181/5 Franca Porvorim, Bardez Goa Penha de next to utkarsh housing society, Penha 2 Bardez Marianella Saldanha 9823422848 118/4 Franca de Franca, Bardez Goa Penha de 3 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa 7821965565 151/1 Franca Penha de 4 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa nill 151/93 Franca Penha de H.No. 583/10, Baman Wada, Penha De 5 Bardez Ujwala Bhimsen Khumbhar 7020063549 151/5 Franca France Brittona Mapusa Goa Penha de 6 Bardez Mumtaz Bi Maniyar Haliwada penha de franca 8007453503 114/7 Franca Penha de 7 Bardez Shobha M. Madiwalar Penha de France Bardez 9823632916 135/4-B Franca Penha de H.No. 377, Virlosa Wada Brittona Penha 8 Bardez Mohan Ramchandra Halarnkar 9822025376 40/3 Franca de Franca Bardez Goa Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 9 Bardez 9765830867 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. 236/20, Ward III, Haliwada, penha 8806789466/ 10 Bardez Mahboobsab Saudagar 134/1 Franca de franca Britona, Bardez Goa 9158034313 Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 11 Bardez 9765830867 135/3, & 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. -

New Data JE.TA 30.01.2014

Name of the post Technical Assistant (Civil) Seat No. Name & Address Category 12 3 G-'001 Richa Shreyas Naik 7/F-4 Kamat Classic IV, Kerant, Caranzalem Goa General G-'002 Ms. Poonam Chalaune Vinayak Building Phase A, Flat No. T4, Nr. Jama Masjid, Panditwada Upper Bazar, Ponda General Goa G-'003 Daksha Prashant Pawar H.No.1470, Manjunath, Don Bosco Junction, Maurida Road, Fatorda Margao Goa. General G-'004 Suraj Jayawant Lolyekar Varaprada, H.No. 236, Nr. Govt. Primary Health Center, Vathadev, Sarvan, Bicholim Goa General G-'005 Mrugali G. Shinde Ashray Bldg., F, Deulwada Bori, Ponda Goa General G-'006 Mithun Mohan Pai G02, Pushpak Raj Co-op Hsg. Society, Nr. Kirti Hotel, Bethoda Road, Durgabhat, Ponda General Goa G-'007 Shailesh U. Naik H. No. 607/6, tanki. Xeldem, Quepem Goa General G-'008 Nitha Goppi M.P.T Colony Bldg. No. 210 2/2, Head Land Sada, Vasco Goa General G-'009 Vinay J. Uchagaonkar H. No. 70, Pontemol, Curchorim Goa General G-'010 Ranjita Prabhakar Parab H. No. 274, arambaol, Pernem Goa General G-'011 Afreen Abulkasim Mulla H. No. 97/A, Maruti Temple, Housing Board - Rumdamol, Navelim, Salcete Goa General G-'012 Rohan R. Gaunkar MPT(CHLD) Colony, B.No. 14, R. No. 22/B, Head Lnd Sada, Vasco Goa General G-'013 Chawan Ravi Dannu H. No. 85, W.No. 7, Nr. Agriculture Office, Valpoi, Sattari Goa General G-'014 Kum. Raisa N. Mesquita Vasudha Housing Colony, H. No. 212D, Alto St. Cruz, Panaji Goa General G-'015 Siddesh M. Kotkar Sudha Colony, Bordem, Bicholim Goa General G-'016 Paresh M. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

Chapter Twelve Jesuit Schools and Missions in The

CHAPTER TWELVE JESUIT SCHOOLS AND MISSIONS IN THE ORIENT 1 MARIA DE DEUS MANSO AND LEONOR DIAZ DE SEABRA View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Missions in India brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico da Universidade de Évora The Northern Province: Goa 2 On 27 th February 1540, the Papal Bull Regimini Militantis Eclesiae established the official institution of The Society of Jesus, centred on Ignacio de Loyola. Its creation marked the beginning of a new Order that would accomplish its apostolic mission through education and evangelisation. The Society’s first apostolic activity was in service of the Portuguese Crown. Thus, Jesuits became involved within the missionary structure of the Portuguese Patronage and ended up preaching massively across non-European spaces and societies. Jesuits achieved one of the greatest polarizations and novelties of their charisma and religious order precisely in those ultramarine lands obtained by Iberian conquest and treatises 3. Among other places, Jesuits were active in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan and China. Their work gave birth to a new concept of mission, one which, underlying the Society’s original evangelic impulses, started to be organised around a dynamic conception of “spiritual conquest” aimed at converting to the Roman Catholic faith all those who “simply” ignored or had strayed from Church doctrines. In India, Jesuits created the Northern (Goa) and the Southern (Malabar) Provinces. One of their characteristics was the construction of buildings, which served as the Mission’s headquarters and where teaching was carried out. Even though we have a new concept of college nowadays, this was not a place for schooling or training, but a place whose function was broader than the one we attribute today. -

District Census Handbook, North Goa

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 6 GOA DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOK PART XII-A AND XII-B VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY AND VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT NORTH GOA DISTRICT S. RAJENDRAN DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, GOA 1991 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS OF GOA ( All the Census Publications of this State will bear Series No.6) Central Government Publications Part Administration Report. Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration. (For Official use only). Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation. Part II General Population Tables Part II-A General Population Tables-A- Series. Part II-B Primary Census Abstract. Part III General Economic Tables Part III-A B-Series tables '(B-1 to B-5, B-l0, B-II, B-13 to B -18 and B-20) Part III-B B-Series tables (B-2, B-3, B-6 to B-9, B-12 to B·24) Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part IV-A C-Series tables (Tables C-'l to C--6, C-8) Part IV -B C.-Series tables (Table C-7, C-9, C-lO) Part V Migration Tables Part V-A D-Series tables (Tables D-l to D-ll, D-13, D-15 to D- 17) Part V-B D- Series tables (D - 12, D - 14) Part VI Fertility Tables F-Series tables (F-l to F-18) Part VII Tables on Houses and Household Amenities H-Series tables (H-I to H-6) Part VIII Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled SC and ST series tables Tribes (SC-I to SC -14, ST -I to ST - 17) Part IX Town Directory, Survey report on towns and Vil Part IX-A Town Directory lages Part IX-B Survey Report on selected towns Part IX-C Survey Report on selected villages Part X Ethnographic notes and special studies on Sched uled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part XI Census Atlas Publications of the Government of Goa Part XII District Census Handbook- one volume for each Part XII-A Village and Town Directory district Part XII-B Village and Town-wise Primary Census Abstract GOA A ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS' 1991 ~. -

North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr

Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr. No. Venue Date CHC/PHC Municipality 1 CHC Pernem Mandrem ZP Hall, Mandrem 13, 14 june Morjim Sarvajanik Ganapati Hall, Morjim 15, 16 June Harmal Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav Hall, Harmal 17, 18 June Palye GPC Madhlawada, Palye 19, 20 June Keri Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Parse Panchayat hall, Parse 23, 24, June Agarwada-Chopde Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Virnoda Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Korgao Panchayat Hall, Korgao 29, 30 June 2 PHC Casarvanem Varkhand Panchayat Hall, Varkhand 13, 14 june Torse Panchayat Hall 15, 16 June Chandel-Hansapur Panchayat Hall 17, 18 June Ugave Panchayat Hall 19, 20 June Ozari Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Dhargal Panchayat Hall 23, 24, June Ibrampur Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Halarn Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Poroscode Panchayat Hall 29, 30 June 3 CHC Bicholim Latambarce Govt Primary School, Ladfe 13, 14, June Latambarce Govt. Primary School, Nanoda 15th June Van-Maulinguem Govt. Primary School, Maulinguem 16th Jun Menkure Govt. High School, Menkure 17, 18 June Mulgao Govt. Primary School, Shirodwadi 19, 20 Junw Advalpal Govt Primary Middle School, Gaonkarwada 21st Jun Latambarce - Usap / Bhatwadi GPS Usap 23 rd June Latambarce - Dodamarg & Kharpal GPS Dodamarg 25, 26 June Latambarce - Kasarpal & Vadaval GPS Kasarpal 27, 28 June Sal Panchayat Hall, Sal 29-Jun Sal - Kholpewadi/ Punarvasan / Shivajiraje High School, Kholpewadi 30-Jun Sirigao at Mayem Primary Health Centre, Kelbaiwada- Mayem 24th June Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ -

Defining Goan Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 1-12-2006 Defining Goan Identity Donna J. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Young, Donna J., "Defining Goan Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. YOUNG Under the Direction of David McCreery ABSTRACT This is an analysis of Goan identity issues in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries using unconventional sources such as novels, short stories, plays, pamphlets, periodical articles, and internet newspapers. The importance of using literature in this analysis is to present how Goans perceive themselves rather than how the government, the tourist industry, or tourists perceive them. Also included is a discussion of post-colonial issues and how they define Goan identity. Chapters include “Goan Identity: A Concept in Transition,” “Goan Identity: Defined by Language,” and “Goan Identity: The Ancestral Home and Expatriates.” The conclusion is that by making Konkani the official state language, Goans have developed a dual Goan/Indian identity. In addition, as the Goan Diaspora becomes more widespread, Goans continue to define themselves with the concept of building or returning to the ancestral home. INDEX WORDS: Goa, India, Goan identity, Goan Literature, Post-colonialism, Identity issues, Goa History, Portuguese Asia, Official languages, Konkani, Diaspora, The ancestral home, Expatriates DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. -

Series III No. 3.P65

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 18th April, 2013 (Chaitra 28, 1935) SERIES III No. 3 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Note:- There is one Supplementary issue to the Official A. D. Post at her residential address in Goa & Dubai, Gazette, Series III No. 2 dated 12th April, 2013 UAE. However the same were returned by the postal namely, Supplement dated 12-4-2013 from pages authorities with a remark unclaimed. Further since 47 to 60 regarding Notification from Department Smt. Sabina Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro, Staff Nurse of Finance, (Revenue and Expenditure Division), was not honouring the official correspondence Directorate of Small Savings & Lotteries (Goa delivered at her permanent residential address, this State Lotteries). office has also requested the Police Inspector, Panaji GOVERNMENT OF GOA Police Station to serve the said show cause order at her permanent residential address. However, it was Department of Public Health reported by the P. I., Panaji Police Station, that after conducting survey they found that the flat was Goa Medical College, closed and returned the said show cause order to Office of the Dean this office. ___ By the aforesaid act, the said Smt. Sabina Order Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro, Staff Nurse has No. 8/226/96/GMC/E2/413 failed to indicate the permanent address during her unauthorized absence period as required under Smt. Sabina Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro while office instruction. She also left the country without functioning as Staff Nurse in Goa Medical College, prior permission of the competent authority Bambolim, Goa, under the control of the Dean, Goa which she failed to do so thereby violating Rule Medical College has proceeded on Extraordinary 15(1) of the Central Civil Services (Conduct) Rules, Leave for the period of six years w.e.f. -

Official Gazette

I BEGD. GOA - 5 1 Panaji, 31 st October, 1985 (Kartika 9, 19071 SERIES II No_ 31 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOAs DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN Home Department r AND DIU General Branch/Division Department of Personnel and Administrative Reforms Notification Personnel Division No. 2/6/82-HD(G) Part File Order In exercise of the ~wers conferred by the proviSO to sub-section (1) of section 58 E of the Reserve Bank of No. 1/2/83-GA & C India Act, 1934 (Central Act 2 of 1934) (hereinafter referred The Administrator of Goa, Daman and Diu is pleased to to .as the "saJid Act") read with the Government of India, order the following transfer in the cadre of M:amlatdar/Jt. Ministry of Home Affairs, Notification No. U-l1030/3/84-UTL Mamlatdar/Block Development Officer with immediate effect dated 12~-1985. the Administrator of Goa, Daman and Diu and until further orders:- hereby authorises the Police Officers in-charge of the Police (i) Shri s. S. Kantak. Jt. MamIatdar, Quepem is trans stations in the Union Territory of Goa. Daman and Diu ferred and posted as Chief Officer, Sanguem Munici and who are not below the rank of Sub-Inspector, to make pal-COuncil vice.Shri A. C. Kamat transferred. a complaint in writing in respect of any offence pUnishable (it) Shrt A. C. Kamat, Chief Officer, Sanguem Municipal under sub-section (5A) of section 58 B of the said Act to Council is transferred and posted as Jt. M,amIatdar, any Court having jurisdiction. -

Knowing Fr Agnelo

Messages Of Support Collection of Letters and Messages received from supporters. May it be an inspiration to us all to continue in our Prayers and Work towards the Beatification Process Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 1 Dear Friends of the Venerable Fr. Agnelo, I would like first of all to congratulate you on this important milestone in your history - the silver jubilee of your foundation. It is wonderful to see how the association has grown and developed over the last twenty five years. Secondly, I would like to thank all of you for all the great work you have done in our parishes here in London helping people be aware of the great witness to Christ that Fr. Agnelo gave in his life and the various ways you have embodied his spirit of prayer, penance and good works. Finally, I join with in thanking god for the gift of Fr. Agnelo's unstinting devotion to Christ and the Church. He continues to be an inspiration to all of us. With every good wish and blessing, + Bishop Patrick Lynch SS.CC. Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 2 Friends of Venerable Fr. Agnelo (UK) Working for the cause of the Beatification in the UK for 25 years (1989 - 2014) Silver Jubilee Edition 3 A Message from Bishop Howard Tripp On the occasion of the Silver Jubilee of the Founding in the United Kingdom of the Association of the Friends of the Venerable Father Agnelo SFX I send my greetings to the members of the Association of the Friends of the Venerable Father Agnelo established here in the United Kingdom twenty five years ago. -

In the Church 22 36 We Pray That by the Virtue of Mariam Dham Catholic Priestly Ordination of Baptism, the Laity, Especially Church, Narnaul Dn

THE OFFICIAL NEWS MAGAZINE OF DELHI CATHOLIC ARCHDIOCESE VOL. 29, ISSUE 10 OCTOBER 2020 `10 Servant of God Archbishop Geevarghese Mar Ivanios The Laity's Mission in the Church 22 36 We pray that by the virtue of Mariam Dham Catholic Priestly Ordination of baptism, the laity, especially Church, Narnaul Dn. Remijus Tirkey women, may participate more in areas of responsibility in the Church. HOLY FATHER’S PRAYER INTENTION FOR OCTOBER 2020 The Laity's Mission in the Church We pray that by the virtue of baptism, the laity, especially women, may participate more in areas of responsibility in the Church. CONTENTS FROM THE EDITOR 5 The Shepherd’s Voice 8 We Drink from Our Own Wells - XXXXVII Mission of the Laity 9 Musings of the Month 10 Theology & Christian Life - 11 11 Special FR. STANLEY KOZHICHIRA 14 Christus Vivit - 9 17 Parish Roundup 24 School Snippets 32 Diocesan Digest On August 6, 2020, Pope Francis appointed new 37 Calendar of Feasts members to the Vatican's Council for the Economy, and in addition to several cardinals, he also added seven new laypeople to the committee. Six of them are women. PATRON Archbishop Anil J.T. Couto Earlier to this, Pope appointed Francesca Di Giovanni as the EDITOR Undersecretary for Multilateral Affairs in the Secretariat of Fr. Stanely Kozhichira State. Di Giovanni, an Italian lawyer, is the first woman to hold a EDITORIAL BOARD management position in the Vatican's most important office. Augustine Kurien Deepanjali Rao Undersecretary is currently the highest position women have Divya Joy reached so far, and Pope Francis has doubled the number of women FINANCE AND CIRCULATION MANAGER Fr.