Understanding the Response to Portuguese Missionary Methods in India in the 16Th – 17Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

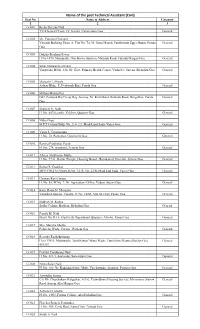

List of Representation /Objection Received Till 31St Aug 2020 W.R.T. Thomas & Araujo Committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No

List of Representation /Objection Received till 31st Aug 2020 w.r.t. Thomas & Araujo committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No. Sy.No. Penha de Leflor, H.no 223/7. BB Borkar Road Alto 1 Bardez Leo Remedios Mendes 9822121352 181/5 Franca Porvorim, Bardez Goa Penha de next to utkarsh housing society, Penha 2 Bardez Marianella Saldanha 9823422848 118/4 Franca de Franca, Bardez Goa Penha de 3 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa 7821965565 151/1 Franca Penha de 4 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa nill 151/93 Franca Penha de H.No. 583/10, Baman Wada, Penha De 5 Bardez Ujwala Bhimsen Khumbhar 7020063549 151/5 Franca France Brittona Mapusa Goa Penha de 6 Bardez Mumtaz Bi Maniyar Haliwada penha de franca 8007453503 114/7 Franca Penha de 7 Bardez Shobha M. Madiwalar Penha de France Bardez 9823632916 135/4-B Franca Penha de H.No. 377, Virlosa Wada Brittona Penha 8 Bardez Mohan Ramchandra Halarnkar 9822025376 40/3 Franca de Franca Bardez Goa Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 9 Bardez 9765830867 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. 236/20, Ward III, Haliwada, penha 8806789466/ 10 Bardez Mahboobsab Saudagar 134/1 Franca de franca Britona, Bardez Goa 9158034313 Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 11 Bardez 9765830867 135/3, & 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. -

James Elisha, "Francis Xavier and Portuguese Administration in India

IJT 46/1&2 (2004), pp. 59-66 Francis Xavier and Portuguese Administration in India James Elisha* Introduction Francis Xavier's attitude to and relationship with the Portuguese colonial administration had been consistently cordial and was based on mutuality of seeking their help for his mission and reciprocating his services in their trade embassies. He found Portuguese presence in India to be advantageous and helpful for his purpose of 'spreading Catholic Christianity to people of other faiths and Malabar Christians.1 Joao III, the king of Portugal, was supportive of the efforts of Xavier to Christianize the people of other faiths and to latinize2 the Malabar Christians in India. Rupture was not very obvious except when conduct and decisions of some administrators were found by Xav,:ier to be detrimental to the process. Xavier used his relationship with the Portugeyl king for his cause and of the Society rather discriminately. ' Xavie~' s relationship with the colonial administration in the coasts of India cannot be studied in isolation with his cordial relationships with the King of Portugal prior to his arrivp} to India in 1542. His cordiality with the Portuguese administrators was just a continuation of his relationship with the court. Xavier utilized his authority from the King to his cause of spreading Catholic Christianity, to oppose the Portugal officials whose presence was a liability to his cause, and to defend the converted communities. He was not uncritically supportive of the Portugal administrators in the land and his relationship with them after his arrival were highly regulated by the sense of a mission from the King and the Pope, and with an added vigor of being a consolation to the local converts. -

New Data JE.TA 30.01.2014

Name of the post Technical Assistant (Civil) Seat No. Name & Address Category 12 3 G-'001 Richa Shreyas Naik 7/F-4 Kamat Classic IV, Kerant, Caranzalem Goa General G-'002 Ms. Poonam Chalaune Vinayak Building Phase A, Flat No. T4, Nr. Jama Masjid, Panditwada Upper Bazar, Ponda General Goa G-'003 Daksha Prashant Pawar H.No.1470, Manjunath, Don Bosco Junction, Maurida Road, Fatorda Margao Goa. General G-'004 Suraj Jayawant Lolyekar Varaprada, H.No. 236, Nr. Govt. Primary Health Center, Vathadev, Sarvan, Bicholim Goa General G-'005 Mrugali G. Shinde Ashray Bldg., F, Deulwada Bori, Ponda Goa General G-'006 Mithun Mohan Pai G02, Pushpak Raj Co-op Hsg. Society, Nr. Kirti Hotel, Bethoda Road, Durgabhat, Ponda General Goa G-'007 Shailesh U. Naik H. No. 607/6, tanki. Xeldem, Quepem Goa General G-'008 Nitha Goppi M.P.T Colony Bldg. No. 210 2/2, Head Land Sada, Vasco Goa General G-'009 Vinay J. Uchagaonkar H. No. 70, Pontemol, Curchorim Goa General G-'010 Ranjita Prabhakar Parab H. No. 274, arambaol, Pernem Goa General G-'011 Afreen Abulkasim Mulla H. No. 97/A, Maruti Temple, Housing Board - Rumdamol, Navelim, Salcete Goa General G-'012 Rohan R. Gaunkar MPT(CHLD) Colony, B.No. 14, R. No. 22/B, Head Lnd Sada, Vasco Goa General G-'013 Chawan Ravi Dannu H. No. 85, W.No. 7, Nr. Agriculture Office, Valpoi, Sattari Goa General G-'014 Kum. Raisa N. Mesquita Vasudha Housing Colony, H. No. 212D, Alto St. Cruz, Panaji Goa General G-'015 Siddesh M. Kotkar Sudha Colony, Bordem, Bicholim Goa General G-'016 Paresh M. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr

Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ Sr. No. Venue Date CHC/PHC Municipality 1 CHC Pernem Mandrem ZP Hall, Mandrem 13, 14 june Morjim Sarvajanik Ganapati Hall, Morjim 15, 16 June Harmal Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav Hall, Harmal 17, 18 June Palye GPC Madhlawada, Palye 19, 20 June Keri Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Parse Panchayat hall, Parse 23, 24, June Agarwada-Chopde Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Virnoda Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Korgao Panchayat Hall, Korgao 29, 30 June 2 PHC Casarvanem Varkhand Panchayat Hall, Varkhand 13, 14 june Torse Panchayat Hall 15, 16 June Chandel-Hansapur Panchayat Hall 17, 18 June Ugave Panchayat Hall 19, 20 June Ozari Panchayat Hall 21, 22 June Dhargal Panchayat Hall 23, 24, June Ibrampur Panchayat Hall 25, 26 June Halarn Panchayat Hall 27, 28, June Poroscode Panchayat Hall 29, 30 June 3 CHC Bicholim Latambarce Govt Primary School, Ladfe 13, 14, June Latambarce Govt. Primary School, Nanoda 15th June Van-Maulinguem Govt. Primary School, Maulinguem 16th Jun Menkure Govt. High School, Menkure 17, 18 June Mulgao Govt. Primary School, Shirodwadi 19, 20 Junw Advalpal Govt Primary Middle School, Gaonkarwada 21st Jun Latambarce - Usap / Bhatwadi GPS Usap 23 rd June Latambarce - Dodamarg & Kharpal GPS Dodamarg 25, 26 June Latambarce - Kasarpal & Vadaval GPS Kasarpal 27, 28 June Sal Panchayat Hall, Sal 29-Jun Sal - Kholpewadi/ Punarvasan / Shivajiraje High School, Kholpewadi 30-Jun Sirigao at Mayem Primary Health Centre, Kelbaiwada- Mayem 24th June Tika Utsav 3 - North Goa Name of the Name of the Panchayat/ -

Series III No. 3.P65

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 18th April, 2013 (Chaitra 28, 1935) SERIES III No. 3 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Note:- There is one Supplementary issue to the Official A. D. Post at her residential address in Goa & Dubai, Gazette, Series III No. 2 dated 12th April, 2013 UAE. However the same were returned by the postal namely, Supplement dated 12-4-2013 from pages authorities with a remark unclaimed. Further since 47 to 60 regarding Notification from Department Smt. Sabina Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro, Staff Nurse of Finance, (Revenue and Expenditure Division), was not honouring the official correspondence Directorate of Small Savings & Lotteries (Goa delivered at her permanent residential address, this State Lotteries). office has also requested the Police Inspector, Panaji GOVERNMENT OF GOA Police Station to serve the said show cause order at her permanent residential address. However, it was Department of Public Health reported by the P. I., Panaji Police Station, that after conducting survey they found that the flat was Goa Medical College, closed and returned the said show cause order to Office of the Dean this office. ___ By the aforesaid act, the said Smt. Sabina Order Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro, Staff Nurse has No. 8/226/96/GMC/E2/413 failed to indicate the permanent address during her unauthorized absence period as required under Smt. Sabina Antonetta D’Cruz e Monteiro while office instruction. She also left the country without functioning as Staff Nurse in Goa Medical College, prior permission of the competent authority Bambolim, Goa, under the control of the Dean, Goa which she failed to do so thereby violating Rule Medical College has proceeded on Extraordinary 15(1) of the Central Civil Services (Conduct) Rules, Leave for the period of six years w.e.f. -

Some Neglected Aspects of the Conversion of Goa: a Socio-Historical Perspective1

SOME NEGLECTED ASPECTS OF THE CONVERSION OF GOA: A SOCIO-HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE1 Rowena Robinson INTRODUCTION he islands of Goa were converted to Catholicism when the Portuguese Tconquered the area in the 16th century by defeating the Adil Shahi rulers.2 The conversion and its impact on Goa - particularly the Goan Inquisition — have generated a fair body of literature. Not all this literature, however, is primarily concerned with analyzing the subject, and some of it leaves the disappointed reader with the feeling that crucial issues are not being addressed or, more unhappily, that what is written is largely apologetic in stance. A critical approach to the subject has still to be firmly established. The conversion of Goa to Catholicism was largely the work of various religious orders which came to Goa in the 16th century. The Franciscans arrived in 1517 and their work was limited mainly to Bardez. The Jesuits were the most influential order that came to Goa.3 They were responsible for the conversion of Tiswadi and Salcete. It was with their arrival in 1542 that missionary activity in Goa received an impetus. The two other orders of significance were the Dominicans, who came in 1548, and the AugustinianS, who came a few years later. These orders were not without their differences,4 but it may be said with some assurance that in their missionary activities in this period they functioned in similar ways. Some observations may be made about the relationship of these missionaries with the conquering power. Not all of those who came as missionaries belonged to the conquering nation; yet they all functioned under the orders of the King of Portugal. -

New Seating Arrangement for SSC Examination 2020

CENTRE : PAINGIN 33 (S) SHRI SHRADHANAND VIDYALAYA (03.06) REVISED SEATING ARRANGEMENT FOR SSC BOARD EXAM MAY 2020 BLOCKS NO. OF STUDENTS SEAT NO BLOCK I 13 27784 TO 27796 BLOCK II 13 27797 TO 27809 BLOCK III 13 27810 TO 27822 BLOCK IV 13 27823 TO 27838 BLOCK V 13 27839 TO 27852 BLOCK VI 13 27853 TO 27865 BLOCK VII 12 27866 TO 27877 BLOCK VIII 12 27878 TO 27894 BLOCK IX 12 27895 TO 27906 BLOCK X 12 27907 TO 27922 BLOCK XI 12 27923 TO 27939 BLOCK XII 12 27941 TO 27954 BLOCK XIII 12 27955 TO 27966 BLOCK XIV 12 27967 TO 27978 BLOCK XV 12 27979 TO 27990 BLOCK XVI 13 27991 TO 28003 27773 TO 27782 ( BLOCK XVII 9 CWSN ) 27771, 27772 & 27783 BLOCK XVIII 3 (CWSN - With reader writer) 211 PROVISION FOR SICK STUDENTS ( Science Lab ) REVISED SEATING ARRANGEMENT FOR SSC EXAMINATION , MAY-JUNE 2020 SEATING ARRANGEMENT SSC EXAMINATION CENTRE NAME: 12 – PANAJI Main Centre: Mary Immaculate Girls’ High School, Panaji Sub Centre No. Name of the school as Sub - Centres School No of code Candidates Sub Centre 1 Mary Immaculate Girls High School, Panaji 11.05 157 Sub Centre 2 a People’s High School, Panaji 11.01 101 161 b Progress High School, Panaji 11.04 60 Sub Centre 3 Don Bosco High School, Panaji 11.02 169 Sub Centre 4 St. Micheal’s High School, Taleigao 11.20 126 Sub Centre 5 a Our Lady of Rosary High School, Dona Paula 11.08 104 127 b Government High School, Dona Paula 11.36 23 Sub Centre 6 a Bal Bharati Vidyamandir, Ribandar 11.14 88 110 b St. -

Maritime Archaeology Of

An overview of shipwreck explorations in Goa waters Sila Tripati1 Abstract Since the beginning of maritime archaeological research in Indian waters, marine records housed in archives of India and abroad provide details of the shipwrecks and the loss of Indian ships in foreign waters. Information on more than 200 shipwrecks in Indian waters has been gathered from archival records and attempts made to explore in Goa, Lakshadweep and Tamil Nadu waters. These shipwrecks are dated to the post 16th century AD. Shipwrecks were explored off Sunchi Reef, St George’s Reef and Amee Shoals in Goa waters. Sunchi Reef and St George’s Reef were wooden hulled sailing ships whereas Amee Shoals was a steel hulled steam engine shipwreck. Sunchi Reef exploration led to the recovery of guns, barrels of handguns, storage jars, Chinese ceramics, elephant tusks, hippopotamus teeth, iron anchors and other items that are evidence of Indo-Portuguese trade and commerce in the 17th century. Exploration off St George’s Reef uncovered timber and terracotta artefacts such as column capitals, drums, ridge tiles, roof and floor tiles and chimney bricks The bricks and tiles have the distinct inscription of Basel Mission Tile works 1865. Amee shoals exploration revealed the remains of a steel hulled steam engine shipwreck in which boilers, boiler bricks, and engine parts were found. The stamps on the flanges and the name on the firebricks suggest a British origin, dating from the 1880s or later. Keywords: Shipwreck, Sunchi Reef, St George’s Reef, Amee Shoals, Goa, Portuguese, Basel Mission Company Introduction The geographical context of this paper lies centrally in Goa. -

November 2019.Cdr

www.goajesuits.com Vol. 28, No. 11, November 2019 Father General announces an Ignatian Year: A Call to Conversion As a province, we celebrated God's gift of two new priests—Malcolm Barreto and Shawn D'Souza—on 19 October. Now there is another celebration for the Society: Father General announced an Ignatian Year in his letter addressed to the entire Society of Jesus on the anniversary of the Bull, RegiminiMilitantis Ecclesiae.“To see all things new in Christ” is the motto of our celebration during the Ignatian year which will begin on 20 May 2021 (the date of Ignatius' injury at the Battle of Pamplona) and will end 14 months later on 31 July 2022. Conversion is at the heart of this Ignatian year. Father Sosa throws out a challenge: “It is my desire that at the heart of this Ignatian year we would hear the Lord calling us, and we would allow him to work our conversion inspired by the personal experience of Ignatius.” When Ignatius' knee was shattered by a cannon ball, he had the opportunity to reflect on his life during his convalescence. And what a difference it made for Ignatius and for the Church! Father General makes this connection with the Universal Apostolic Preferences calling us to conversion at three levels: personal, community, and institutional. During our ongoing Province Apostolic Planning, we ask for this same grace of conversion, “which is necessary for our greater spiritual and apostolic freedom and adaptability. Let us take this opportunity to let God transform our life-mission, according to his will” (Fr General, 2019/23). -

Contribution of Jesuits to Higher Education in Goa: Historical Background of Higher Education of the Jesuits

CONTRIBUTION OF JESUITS TO HIGHER EDUCATION IN GOA: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE JESUITS Savio Abreu, SJ Xavier Centre of Historical Research, Goa 1. Historical Background of Higher Education of the Jesuits Higher education has been synonymous with the Society of Jesus. The founding members of the Society, be it Ignatius or Francis Xa- vier were all University educated and right from the beginning, when the Society was founded on 27th September 1540, Ignatius stressed on a rigorous academic formation for all those who desired to become Jesuits. This tradition of higher education was seen in the Indian subcontinent right from the time when Francis Xavier landed in Goa on 6th May 1542. On his arrival he was requested to take up the responsibility of forming the youth of the seminary as he himself had adorned a chair at the Paris University. On 24th April 1541 the Vicar General of Goa, Miguel Vas and Fr. Diogo de Borba started the Confraternity of the Holy faith. The Confraternity was to propagate the catholic faith and to educate the young converts. It was also decided to establish a seminary for the indigenous boys, where they would be instructed in reading, writing, Portuguese and Latin grammar, Christian doctrine and moral theol- ogy. The work on the seminary of Holy Faith started on 10th November 1541, adjacent to the Church of Our Lady of Light in In/En: St Francis Xavier and the Jesuit Missionary Enterprise. Assimilations between Cultures / San Francisco Javier y la empresa misionera jesuita. Asimilaciones entre culturas, ed. Ignacio Arellano y Carlos Mata Induráin, Pamplona, Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra, 2012 (BIADIG, Biblioteca Áurea Digital-Publicaciones digitales del GRISO), pp.