Indonesia: Rollback in the Time of COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rainforest Foundation Annual Report 2009 P H OTO : W OLTE R SIL V E R a Contents

Rainforest Foundation Annual Report 2009 P H OTO : W OLTE R SIL V E R A Contents FROM THE DIRECTOR 4–5 LATIN AMERICA The Amazon 6–7 No Borders 7 Brazil and Peru 8–9 Paraguay, Bolivia, Venezuela, Ecuador 10–11 ASIA Southeast Asia 12 Malaysia 13 Indonesia 14–15 Papua/New Guinea 16–17 AFRICA Central Africa 18 DR Congo 18–19 CLIMATE 20–21 POLICY AND PROMOTION 22 20TH ANNIVERSARY 23 INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION 24–25 ADMINISTRATION 25 FUNDING AND SUPPORTERS 2–27 ACCOUNTS 28–31 The Rainforest Foundation The Rainforest Foundation fights to preserve the world’s rain forests and ensure the rights of indigenous peoples, in cooperation with local indigenous and environmental organizations in Southeast Asia, Central Africa and the Amazon. In Norway we work on raising awareness about the rain- forest and preventing Norwegian politics and business interests from contributing to its destruction. The Rainforest Foundation was founded in 1989. We are a part of the international network Rainforest Foundation, with sister organizations in the US and the UK. Project support is financed by public authorities, the annual school project «Operation Day’s Work», private donors and sponsors. Five Norwegian organizations are members: Earth Norway, Nature and Youth, the children’s environmental organization «Eco-agents», the Development Fund and The Future in Our Hands. 2 RAINFOREST FOUNDATION • ANNUAL REPORT 2009 RAINFOREST FOUNDATION • ANNUAL REPORT 2009 3 ANNUAL REPORT 2009 FROM THE DIRECTOR A global player with solid local contact M AP : UNEP -WCMC Director for the Rainforest » vENEZuEla Foundation, » Malaysia Lars Løvold » ECuaDoR » DRC Twenty years have passed since the » iNDoNEsia » PaPua musician Sting and the Indian leader Rainforest: » PERu » BRaZil NEW GuiNEa Raoni visited Oslo with their appeal to preserve the rainforest and create a Today Originally major new Indian territory in the » Bolivia Brazilian Amazon. -

33 CHAPTER II GENERAL DESCRIPTION of SERUYAN REGENCY 2.1. Geographical Areas Seruyan Regency Is One of the Thirteen Regencies W

CHAPTER II GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF SERUYAN REGENCY 2.1. Geographical Areas Seruyan Regency is one of the thirteen regencies which comprise the Central Kalimantan Province on the island of Kalimantan. The town of Kuala Pembuang is the capital of Seruyan Regency. Seruyan Regency is one of the Regencies in Central Kalimantan Province covering an area around ± 16,404 Km² or ± 1,670,040.76 Ha, which is 11.6% of the total area of Central Kalimantan. Figure 2.1 Wide precentage of Seruyan regency according to Sub-District Source: Kabupaten Seruyan Website 2019 Based on Law Number 5 Year 2002 there are some regencies in Central Kalimantan Province namely Katingan regency, Seruyan regency, Sukamara regency, Lamandau regency, Pulang Pisau regency, Gunung Mas regency, Murung Raya regency, and Barito Timur regency 33 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Year 2002 Number 18, additional State Gazette Number 4180), Seruyan regency area around ± 16.404 km² (11.6% of the total area of Central Kalimantan). Administratively, to bring local government closer to all levels of society, afterwards in 2010 through Seruyan Distric Regulation Number 6 year 2010 it has been unfoldment from 5 sub-districts to 10 sub-districts consisting of 97 villages and 3 wards. The list of sub-districts referred to is presented in the table below. Figure 2.2 Area of Seruyan Regency based on District, Village, & Ward 34 Source: Kabupaten Seruyan Website 2019 The astronomical position of Seruyan Regency is located between 0077'- 3056' South Latitude and 111049 '- 112084' East Longitude, with the following regional boundaries: 1. North border: Melawai regency of West Kalimantan Province 2. -

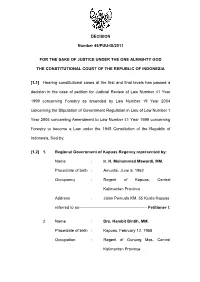

DECISION Number 45/PUU-IX/2011 for the SAKE OF

DECISION Number 45/PUU-IX/2011 FOR THE SAKE OF JUSTICE UNDER THE ONE ALMIGHTY GOD THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA [1.1] Hearing constitutional cases at the first and final levels has passed a decision in the case of petition for Judicial Review of Law Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry as amended by Law Number 19 Year 2004 concerning the Stipulation of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law Number 1 Year 2004 concerning Amendment to Law Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry to become a Law under the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, filed by: [1.2] 1. Regional Government of Kapuas Regency represented by: Name : Ir. H. Muhammad Mawardi, MM. Place/date of birth : Amuntai, June 5, 1962 Occupancy : Regent of Kapuas, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Pemuda KM. 55 Kuala Kapuas referred to as --------------------------------------------------- Petitioner I; 2. Name : Drs. Hambit Bintih, MM. Place/date of birth : Kapuas, February 12, 1958 Occupation : Regent of Gunung Mas, Central Kalimantan Province 2 Address : Jalan Cilik Riwut KM 3, Neighborhood Ward 011, Neighborhood Block 003, Kuala Kurun Village, Kuala Kurun District, Gunung Mas Regency referred to as -------------------------------------------------- Petitioner II; 3. Name : Drs. Duwel Rawing Place/date of birth : Tumbang Tarusan, July 25, 1950 Occupation : Regent of Katingan, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Katunen, Neighborhood Ward 008, Neighborhood Block 002, Kasongan Baru Village, Katingan Hilir District, Katingan Regency referred to as -------------------------------------------------- Petitioner III; 4. Name : Drs. H. Zain Alkim Place/date of birth : Tampa, July 11, 1947 Occupation : Regent of Barito Timur, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Ahmad Yani, Number 97, Neighborhood Ward 006, Neighborhood Block 001, Mayabu Village, Dusun Timur District, Barito Timur Regency 3 referred to as ------------------------------------------------- Petitioner IV; 5. -

“People of the Jungle”

“PEOPLE OF THE JUNGLE” Adat, Women and Change among Orang Rimba Anne Erita Venåsen Berta Master thesis submitted to the Department of Social Anthropology UNIVERSITY OF OSLO May 2014 II “PEOPLE OF THE JUNGLE” Adat, Women and Change among Orang Rimba Anne Erita Venåsen Berta III © Anne Erita Venåsen Berta 2014 “People of the Jungle”: Adat, Women and Change among Orang Rimba Anne Erita Venåsen Berta http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo IV Abstract In a small national park in the Jambi province of Sumatra, Indonesia lives Orang Rimba. A group of matrilineal, animist, hunter-gather and occasional swidden cultivating forest dwellers. They call themselves, Orang Rimba, which translates to ‘People of the Jungle’, indicating their dependency and their connectedness with the forest. Over the past decades the Sumatran rainforest have diminished drastically. The homes of thousands of forest dwellers have been devastated and replaced by monoculture oil palm plantations that push Orang Rimba away from their customary land. Development projects, national and international governments, the Non-Governmental Organisation KKI Warsi through initiatives such as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) seek to conserve forests and ‘develop peoples’. In the middle of all this Orang Rimba are struggling to keep their eminence as a group who define themselves in contrast to ‘others’, people of the ‘outside’. The core question this thesis asks is how physical changes in the environment have affected Orang Rimba of Bukit Duabelas and their perceptions of the world. It answers the question by going through Orang Rimba ‘now and then’, drawing mainly on the works of Steven Sager (2008) and Øyvind Sandbukt (1984, 1988, 2000 and in conversation) as well as other comparable literature to compare. -

Strategi Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara Dalam Pemberdayaan

WACANA Vol. 13 No. 1 Januari 2010 ISSN. 1411-0199 STRATEGI PEMERINTAH KABUPATEN SUKAMARA DALAM PEMBERDAYAAN EKONOMI MASYARAKAT (Studi Tentang Pemberdayaan Usaha Kecil Pembuatan Kerupuk Ikan Di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara Propinsi Kalimantan Tengah) Strategies of the Sukamara Regency Government in Empowering Community Economic (Study about Empowerment of Fish Chips Small Businesses at the Sukamara Sub District, Central Kalimantan). ISWAN GEMAYANA Mahasiswa Program Magister Ilmu Administrasi Publik, PPSUB Sukanto dan Ismani HP Dosen Jurusan Ilmu Administrasi Publik, FIAUB ABSTRAK Penelitian berawal dari latar belakang masalah tentang upaya oleh pemerintah kabupaten Sukamara dalam memberdayakan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara kabupaten Sukamara mengingat sampai saat ini, masih belum mampu menjadikan usaha kecil pembuat kerupuk ikan sebagai produk unggulan. Tujuan dari penelitian ini ialah untuk mendiskripsikan dan menganalisis: (1) Potensi usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara, (2) Strategi pemberdayaan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara dan (3) Faktor-faktor penghambat dan pendukung dalam pemberdayaan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara. Jenis penelitian yang dilakukan dalam penelitian ini adalah penelitian kwalitatif dengan lokasi penelitian pada pengusaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara Propinsi Kalimantan Tengah. Analisis yang dilakukan dengan mengikuti model Miles Huberman yaitu analisis interaktif. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa upaya yang dilakukan oleh Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara dalam memberdayakan pengusaha kecil pembuat kerupuk ikan telah dilakukan, namun belum bisa dilakukan secara maksimal mengingat Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara sebagai pemerintahan baru hasil pemekaran mengalami beberapa kendala diantaranya keterbatasan personil, alokasi anggaran masih terserap untuk pembuatan infrastruktur gedung-gedung perkantoran pemerintah dan penataan organisasi kedalam. -

Last Chance to Save Bukit Tigapuluh

Last Chance to Save Bukit Tigapuluh Sumatran tigers, elephants, orangutans and indigenous tribes face local extinction, along with forest Published by: KKI Warsi / Frankfurt Zoological Society / Eyes on the Forest / WWF-Indonesia 14 December 2010 Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Introduction to a disappearing landscape ............................................................................................. 5 3. Conservation and carbon values ............................................................................................................. 7 3.1. Fauna diversity ..................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2. Flora diversity ....................................................................................................................................... 9 3.3. Environmental and carbon values ..................................................................................................... 10 3.4. Social values ......................................................................................................................................... 11 4. Conservation efforts and natural forest loss ........................................................................................ 14 5. Natural forests lost until 2010 ............................................................................................................. -

Identification of Factors Affecting Food Productivity Improvement in Kalimantan Using Nonparametric Spatial Regression Method

Modern Applied Science; Vol. 13, No. 11; 2019 ISSN 1913-1844 E-ISSN 1913-1852 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Identification of Factors Affecting Food Productivity Improvement in Kalimantan Using Nonparametric Spatial Regression Method Sifriyani1, Suyitno1 & Rizki. N. A.2 1Statistics Study Programme, Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. 2Mathematics Education Study Programme, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. Correspondence: Sifriyani, Statistics Study Programme, Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 8, 2019 Accepted: October 23, 2019 Online Published: October 24, 2019 doi:10.5539/mas.v13n11p103 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v13n11p103 Abstract Problems of Food Productivity in Kalimantan is experiencing instability. Every year, various problems and inhibiting factors that cause the independence of food production in Kalimantan are suffering a setback. The food problems in Kalimantan requires a solution, therefore this study aims to analyze the factors that influence the increase of productivity and production of food crops in Kalimantan using Spatial Statistics Analysis. The method used is Nonparametric Spatial Regression with Geographic Weighting. Sources of research data used are secondary data and primary data obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture -

Indonesia 12

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Indonesia Sumatra Kalimantan p509 p606 Sulawesi Maluku p659 p420 Papua p464 Java p58 Nusa Tenggara p320 Bali p212 David Eimer, Paul Harding, Ashley Harrell, Trent Holden, Mark Johanson, MaSovaida Morgan, Jenny Walker, Ray Bartlett, Loren Bell, Jade Bremner, Stuart Butler, Sofia Levin, Virginia Maxwell PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Indonesia . 6 JAVA . 58 Malang . 184 Indonesia Map . 8 Jakarta . 62 Around Malang . 189 Purwodadi . 190 Indonesia’s Top 20 . 10 Thousand Islands . 85 West Java . 86 Gunung Arjuna-Lalijiwo Need to Know . 20 Reserve . 190 Banten . 86 Gunung Penanggungan . 191 First Time Indonesia . 22 Merak . 88 Batu . 191 What’s New . 24 Carita . 88 South-Coast Beaches . 192 Labuan . 89 If You Like . 25 Blitar . 193 Ujung Kulon Month by Month . 27 National Park . 89 Panataran . 193 Pacitan . 194 Itineraries . 30 Bogor . 91 Around Bogor . 95 Watu Karang . 195 Outdoor Adventures . 36 Cimaja . 96 Probolinggo . 195 Travel with Children . 52 Cibodas . 97 Gunung Bromo & Bromo-Tengger-Semeru Regions at a Glance . 55 Gede Pangrango National Park . 197 National Park . 97 Bondowoso . 201 Cianjur . 98 Ijen Plateau . 201 Bandung . 99 VANY BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK © BRANDS/SHUTTERSTOCK VANY Kalibaru . 204 North of Bandung . 105 Jember . 205 Ciwidey & Around . 105 Meru Betiri Bandung to National Park . 205 Pangandaran . 107 Alas Purwo Pangandaran . 108 National Park . 206 Around Pangandaran . 113 Banyuwangi . 209 Central Java . 115 Baluran National Park . 210 Wonosobo . 117 Dieng Plateau . 118 BALI . 212 Borobudur . 120 BARONG DANCE (P275), Kuta & Southwest BALI Yogyakarta . 124 Beaches . 222 South Coast . 142 Kuta & Legian . 222 Kaliurang & Kaliadem . 144 Seminyak . -

Usaid Lestari

USAID LESTARI LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL BRIEF OPTIMIZATION OF REFORESTATION FUND IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN MARCH 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Tetra Tech ARD. This publication was prepared for review by the United States Agency for International Development under Contract # AID-497-TO-15-00005. The period of this contract is from July 2015 to July 2020. Implemented by: Tetra Tech P.O. Box 1397 Burlington, VT 05402 Tetra Tech Contacts: Reed Merrill, Chief of Party [email protected] Rod Snider, Project Manager [email protected] USAID LESTARI – Optimization of Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Page | i LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL BRIEF OPTIMIZATION OF REFORESTATION FUND IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN MARCH 2020 DISCLAIMER This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Tetra Tech ARD and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID LESTARI – Optimization of Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Page | ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations iv Executive Summary 1 Introduction: Reforestation Fund, from Forest to Forest 3 Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Province: Answering the Uncertainty 9 LESTARI Facilitation: Optimization of Reforestation Fund through Improving FMU Role 15 Results of Reforestation Fund Optimization -

2016 Sustainability Benchmark: Indonesian Palm Oil Growers

2016 Sustainability Benchmark: Indonesian Palm Oil Growers Chain Reaction Research 1320 19th Street NW, Suite 400 Key Findings Washington, DC 20036 United States The sustainable purchasing policies of main traders/processors have strengthened Website: www.chainreactionresearch.com the sustainability policies and practices of 4 of the 10 largest palm oil growers listed Email: [email protected] on the Indonesian stock exchange (IDX). Authors: Albert ten Kate, Aidenvironment Gabriel Thoumi, CFA, FRM, Climate Advisers Most of the IDX-listed palm oil growers still have poor sustainability standards. Eric Wakker, Aidenvironment December 2016. The IDX-listed palm oil growing companies PT Tunas Baru Lampung and PT Sawit Sumbermas Sarana are presently clearing forests and/or peatlands. The world’s top food processing companies Nestlé and Unilever are among their customers. The methodologies used for scoring The sustainability policies and recent practices of 10 largest IDX-listed palm oil growers the companies in this report are were analyzed and ranked. Together these companies harvest around 10 percent of the described in Appendix 1 and world’s oil palm. Climate change, biodiversity loss and human rights abuses were the Appendix 2. key elements of screening. The companies could score a total of 12 points (Appendix 1): Aligning with No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) policies (maximum 6 points) Active membership of the RSPO (maximum 3 points) Recent practices (maximum 3 points) The scores were transferred into the categories red (policies and practices inadequate), orange (should be improved), and green (likely not perfect, yet on the way). Figure 1 below shows the final scores (largest palm oil growers mentioned first). -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 84 International Conference on Ethics in Governance (ICONEG 2016) Local Knowledge of Dayak Tomun Lamandau About the Honey Harvest Brian L. Djumaty Antakusuma University Pangkalan Bun, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract--Culture is the result of a set of experiences provided by observations and documents [5]. This type of research is nature. like the local knowledge to harvest honey by society descriptive. Descriptive Aiming to describe accurately the Tomun Lamandau, Central Borneo. This research uses characteristics and focus on the fundamental question of descriptive qualitative method and data collection techniques "How" for trying to acquire and convey the facts clearly and including observation, interviews, and documentation. The accurately [6]. The goal is to describe accurately the results showed that society already have knowledge about protecting nature in a way as not to damage the honeycomb and characteristics of a phenomenon or problem studied so as to tree. Some of the equipment used to harvest the honey has been convey the facts clearly and accurately [7]. modified. B. Research Field Keywords: Local Knowledge, Dayaknese, Protecting Nature This research was carried out starting from a survey of Introduction student placement Field Work Experience (KKN) Antakusuma I. INTRODUCTION University in Kabupatan Lamandau. Writer fascinated by the Based on data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) in culture of the local community. One of them is the knowledge 2010, there are more than 300 ethnic groups or tribes 1.340 or of local communities to harvest the honey. more than 300 ethnic groups. The diversity of the culture of This research was conducted in June-August 2016. -

Attacks on Forest-Dependent Communities in Indonesia and Resistance Stories

ATTACKS ON FOREST-DEPENDENT COMMUNITIES IN INDONESIA AND RESISTANCE STORIES Photo: Sahabat Hutan Harapan A Compilation of WRM Bulletin Articles March 2021 WORLD RAINFOREST MOVEMENT Attacks on Forest-Dependent Communities in Indonesia and Resistance Stories A Compilation of WRM Bulletin Articles March 2021 INDEX INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 4 ATTACKS ON FOREST-DEPENDENT COMMUNITIES .............................................. 7 “Paper Dragons”: Timber Plantation Corporations and Creditors in Indonesia ............... 7 Large-scale investments and climate conservation initiatives destroy forests and people’s territories ................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Indonesia: Proposed laws threaten to reinstate corporate control over agrodiversity ................................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Indonesia: Exploitation of women and violation of their rights in oil palm plantations ................................................................................................................................................................. 16 Indonesia: Oil palm plantations and their trace of violence against women ............................ 20 Indonesia: