Delineating the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

The US Anti- Apartheid Movement and Civil Rights Memory

BRATYANSKI, JENNIFER A., Ph.D. Mainstreaming Movements: The U.S. Anti- Apartheid Movement and Civil Rights Memory (2012) Directed by Dr. Thomas F. Jackson. 190pp. By the time of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, in 1990, television and film had brought South Africa’s history of racial injustice and human rights violations into living rooms and cinemas across the United States. New media formats such as satellite and cable television widened mobilization efforts for international opposition to apartheid. But at stake for the U.S. based anti-apartheid movement was avoiding the problems of media misrepresentation that previous transnational movements had experienced in previous decades. Movement participants and supporters needed to connect the liberation struggles in South Africa to the historical domestic struggles for racial justice. What resulted was the romanticizing of a domestic civil rights memory through the mediated images of the anti-apartheid struggle which appeared between 1968 and 1994. Ultimately, both the anti-apartheid and civil rights movements were sanitized of their radical roots, which threatened the ongoing struggles for black economic advancement in both countries. MAINSTREAMING MOVEMENTS: THE U.S. ANTI-APARTHEID MOVEMENT AND CIVIL RIGHTS MEMEORY by Jennifer A. Bratyanski A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2012 Approved by Thomas F. Jackson Committee -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

DOUG Mcadam CURRENT POSITION

DOUG McADAM CURRENT POSITION: The Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor of Sociology (with affiliations in American Studies, Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, and the Interdisciplinary Program in Environmental Research) Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 PRIOR POSITIONS: Fall 2001 – Summer 2005 Director, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, CA Fall 1998 – Summer 2001 Professor, Department of Sociology, Stanford University Spring 1983 - Summer 1998 Assistant to Full Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Arizona Fall 1979 - Winter 1982 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, George Mason University EDUCATION: 1973 Occidental College Los Angeles, California B.S., Sociology 1977 State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, New York M.A., Sociology 1979 State University of New York at Stony Brook Stony Brook, New York Ph.D., Sociology FELLOWSHIPS AND OTHER HONORS: Post Graduate Visiting Scholar, Russell Sage Foundation, 2013-14. DOUG McADAM Page 2 Granted 2013 “Award for Distinguished Scholar,” by University of Wisconsin, Whitewater, March 2013. Named the Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor of Sociology, 2013. Awarded the 2012 Joseph B. and Toby Gittler Prize, Brandeis University, November 2012 Invited to deliver the Gunnar Myrdal Lecture at Stockholm University, May 2012 Invited to deliver the 2010-11 “Williamson Lecture” at Lehigh University, October 2010. Named a Phi Beta Kappa Society Visiting Scholar for 2010-11. Named Visiting Scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation for 2010-11. (Forced to turn down the invitation) Co-director of a 2010 Social Science Research Council pre-dissertation workshop on “Contentious Politics.” Awarded the 2010 Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service Research Prize, given annually to a scholar for their contributions to the study of “civic engagement.” Awarded the John D. -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

Read the Full PDF

Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism Gary J. Schmitt, Editor The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmitt, Gary James, 1952– Safety, liberty, and Islamist terrorism : American and European approaches to domestic counterterrorism / Gary J. Schmitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4333-2 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4333-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4349-3 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4349-6 (pbk.) [etc.] 1. United States—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations— United States. 3. National security—International cooperation. 4. Security, International. I. Title. JZ1480.A54S38 2010 363.325'16094—dc22 2010018324 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cover photographs: Double Decker Bus © Stockbyte/Getty Images; Freight Yard © Chris Jongkind/ Getty Images; Manhattan Skyline © Alessandro Busà/ Flickr/Getty Images; and New York, NY, September 13, 2001—The sun streams through the dust cloud over the wreckage of the World Trade Center. Photo © Andrea Booher/ FEMA Photo News © 2010 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

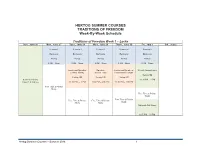

HERTOG SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS of FREEDOM Week-By-Week Schedule

HERTOG SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS OF FREEDOM Week-By-Week Schedule Traditions of Freedom Week 1 – Locke Sun., June 26 Mon., June 27 Tues., June 28 Wed., June 29 Thurs., June 30 Fri., July 1 Sat., July 2 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon Lunch and Speaker: Speaker: Lunch and Speakers: Weekly Group Lunch Charles Murray Steven Teles Fred and Kim Kagan Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Summer Fellows 12:30 PM – 2 PM Class 1 & 2 Arrive 12:30 PM – 2 PM 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM 12:30 PM – 2:00 PM Free Time & Private Study Free Time & Private Study Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Study Study Study Nationals Ball Game 6:05 PM – 10 PM Hertog Summer Courses – Summer 2016 1 Traditions of Freedom Week 2 – Burke Sun., July 3 Mon., July 4 Tues., July 5 Wed., July 6 Thurs., July 7 Fri., July 8 Sat., July 9 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Levine Levine Levine Levine Levine Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon Straussian Picnic Grad School Lunch with Weekly Group Lunch Summer Fellows American University Free Time & Private Alan Levine Free Time & Private Class 1 & 2 Depart (4400 Massachusetts Study Study Before 11 am Ave NW) Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Noon – 4 PM 12:30 PM – 2 PM 12:30 PM – 2 PM Speaker: Speaker: Leon Kass Chris DeMuth Free Time & Private Hertog HQ Free Time & Private Hertog HQ Free Time & Private Study Study Study 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Study Study Hertog Summer Courses – Summer 2016 2 HERTOG 2016 SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS OF FREEDOM SYLLABUS This two-week unit will explore foundations of conservative political thought in the works of John Locke and Edmund Burke. -

The Equal Rights Amendment Revisited

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 94 | Issue 2 Article 10 1-2019 The qualE Rights Amendment Revisited Bridget L. Murphy Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. 937 (2019). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\94-2\NDL210.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-DEC-18 7:48 THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT REVISITED Bridget L. Murphy* [I]t’s humiliating. A new amendment we vote on declaring that I am equal under the law to a man. I am mortified to discover there’s reason to believe I wasn’t before. I am a citizen of this country. I am not a special subset in need of your protection. I do not have to have my rights handed down to me by a bunch of old, white men. The same [Amendment] Fourteen that protects you, protects me. And I went to law school just to make sure. —Ainsley Hayes, 20011 If I could choose an amendment to add to this constitution, it would be the Equal Rights Amendment . It means that women are people equal in stature before the law. And that’s a fundamental constitutional principle. I think we have achieved that through legislation. -

How Sex Got Into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism As a Maker of Public Policy

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 1 June 1991 How Sex Got into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy Jo Freeman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Jo Freeman, How Sex Got into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy, 9(2) LAW & INEQ. 163 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol9/iss2/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. How "Sex" Got Into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy Jo Freeman* The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a milestone of federal legis- lation. Like much major legislation, it had "incubated" for decades but was birthed in turmoil. On June 19, 1963, after the civil rights movement of the fifties and early sixties had focused national at- tention on racial injustice, President John F. Kennedy sent a draft omnibus civil rights bill to the Congress.' On February 8, 1964, while the bill was being debated on the House floor, Rep. Howard W. Smith of Virginia, Chairman of the Rules Committee and staunch opponent of all civil rights legislation, rose up and offered a one-word amendment to Title VII, which prohibited employment discrimination. He proposed to add "sex" to the bill in order "to prevent discrimination against another minority group, the women . "2 This stimulated several hours of humorous debate, later en- shrined as "Ladies Day in the House," 3 before the amendment was passed by a teller vote of 168 to 133. -

Conversations with Bill Kristol

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Peter Berkowitz, Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution Taped, March 2, 2018 Table of Contents I: Liberal Democracy and its Critics 0:15 – 39:35 II: Reclaiming the Liberal Tradition 39:35 – 1:04:48 I: Liberal Democracy and its Critics (0:15 – 39:35) KRISTOL: Hi, I’m Bill Kristol, welcome back to CONVERSATIONS. I am joined today by my friend Peter Berkowitz, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, author of many books, articles, fine teacher, formerly at Harvard University – I have to mention that out of pride there – and the author, maybe for the point of this conversation, the one book I guess I might mention is Virtue and the Making of Modern Liberalism, since we are going to talk about liberalism. Liberalism in the broad sense, though: liberal democracy; the liberal tradition, which, we’ll get to this, whether it includes some of modern conservatism, etc. So, liberalism is under assault in a way that maybe we wouldn’t have expected ten, fifteen years ago. Sort of an intellectual, I would say, assault. It seems that way to me. Is that your sense, too? BERKOWITZ: Yes, and it’s a kind of renewed assault, right? Because what we think of as liberalism – and, of course, here I guess we should pause, you kind of gestured at it in the introduction – is what everybody thinks of as “Liberalism” in ordinary political discourse, right? We think of the left wing of the Democratic Party; we think of using government to promote equality, to regulate, to redistribute. -

Women's Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly

Sara M. EvanS Women’s Liberation: Seeing the Revolution Clearly Approximately fifty members of the five Chicago radical women’s groups met on Saturday, May 18, 1968, to hold a citywide conference. The main purposes of the conference were to create and strengthen ties among groups and individuals, to generate a heightened sense of common history and purpose, and to provoke imaginative pro- grammatic ideas and plans. In other words, the conference was an early step in the process of movement building. —Voice of Women’s Liberation Movement, June 19681 EvEry account of thE rE-EmErgEncE of feminism in the United States in the late twentieth century notes the ferment that took place in 1967 and 1968. The five groups meeting in Chicago in May 1968 had, for instance, flowered from what had been a single Chicago group just a year before. By the time of the conference in 1968, activists who used the term “women’s liberation” understood themselves to be building a movement. Embedded in national networks of student, civil rights, and antiwar movements, these activists were aware that sister women’s liber- ation groups were rapidly forming across the country. Yet despite some 1. Sarah Boyte (now Sara M. Evans, the author of this article), “from Chicago,” Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, June 1968, p. 7. I am grateful to Elizabeth Faue for serendipitously sending this document from the first newsletter of the women’s liberation movement created by Jo Freeman. 138 Feminist Studies 41, no. 1. © 2015 by Feminist Studies, Inc. Sara M. Evans 139 early work, including my own, the particular formation calling itself the women’s liberation movement has not been the focus of most scholar- ship on late twentieth-century feminism.