Download the Issue As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

NOTES Introduction 1. Robert Kagan to George Packer. Cited in Packer’s The Assassin’s Gate: America In Iraq (Faber and Faber, London, 2006): 38. 2. Stefan Halper and Jonathan Clarke, America Alone: The Neoconservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004): 9. 3. Critiques of the war on terror and its origins include Gary Dorrien, Imperial Designs: Neoconservatism and the New Pax Americana (Routledge, New York and London, 2004); Francis Fukuyama, After the Neocons: America At the Crossroads (Profile Books, London, 2006); Ira Chernus, Monsters to Destroy: The Neoconservative War on Terror and Sin (Paradigm Publishers, Boulder, CO and London, 2006); and Jacob Heilbrunn, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons (Doubleday, New York, 2008). 4. A report of the PNAC, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century, September 2000: 76. URL: http:// www.newamericancentury.org/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf (15 January 2009). 5. On the first generation on Cold War neoconservatives, which has been covered far more extensively than the second, see Gary Dorrien, The Neoconservative Mind: Politics, Culture and the War of Ideology (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1993); Peter Steinfels, The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1979); Murray Friedman, The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005); Murray Friedman ed. Commentary in American Life (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2005); Mark Gerson, The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to the Culture Wars (Madison Books, Lanham MD; New York; Oxford, 1997); and Maria Ryan, “Neoconservative Intellectuals and the Limitations of Governing: The Reagan Administration and the Demise of the Cold War,” Comparative American Studies, Vol. -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

Read the Full PDF

Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism Gary J. Schmitt, Editor The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmitt, Gary James, 1952– Safety, liberty, and Islamist terrorism : American and European approaches to domestic counterterrorism / Gary J. Schmitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4333-2 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4333-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4349-3 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4349-6 (pbk.) [etc.] 1. United States—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations— United States. 3. National security—International cooperation. 4. Security, International. I. Title. JZ1480.A54S38 2010 363.325'16094—dc22 2010018324 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cover photographs: Double Decker Bus © Stockbyte/Getty Images; Freight Yard © Chris Jongkind/ Getty Images; Manhattan Skyline © Alessandro Busà/ Flickr/Getty Images; and New York, NY, September 13, 2001—The sun streams through the dust cloud over the wreckage of the World Trade Center. Photo © Andrea Booher/ FEMA Photo News © 2010 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

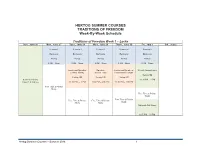

HERTOG SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS of FREEDOM Week-By-Week Schedule

HERTOG SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS OF FREEDOM Week-By-Week Schedule Traditions of Freedom Week 1 – Locke Sun., June 26 Mon., June 27 Tues., June 28 Wed., June 29 Thurs., June 30 Fri., July 1 Sat., July 2 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Berkowitz Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon Lunch and Speaker: Speaker: Lunch and Speakers: Weekly Group Lunch Charles Murray Steven Teles Fred and Kim Kagan Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Summer Fellows 12:30 PM – 2 PM Class 1 & 2 Arrive 12:30 PM – 2 PM 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM 12:30 PM – 2:00 PM Free Time & Private Study Free Time & Private Study Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Study Study Study Nationals Ball Game 6:05 PM – 10 PM Hertog Summer Courses – Summer 2016 1 Traditions of Freedom Week 2 – Burke Sun., July 3 Mon., July 4 Tues., July 5 Wed., July 6 Thurs., July 7 Fri., July 8 Sat., July 9 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Levine Levine Levine Levine Levine Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog Hertog 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon 9 AM – Noon Straussian Picnic Grad School Lunch with Weekly Group Lunch Summer Fellows American University Free Time & Private Alan Levine Free Time & Private Class 1 & 2 Depart (4400 Massachusetts Study Study Before 11 am Ave NW) Hertog HQ Hertog HQ Noon – 4 PM 12:30 PM – 2 PM 12:30 PM – 2 PM Speaker: Speaker: Leon Kass Chris DeMuth Free Time & Private Hertog HQ Free Time & Private Hertog HQ Free Time & Private Study Study Study 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM Free Time & Private Free Time & Private Study Study Hertog Summer Courses – Summer 2016 2 HERTOG 2016 SUMMER COURSES TRADITIONS OF FREEDOM SYLLABUS This two-week unit will explore foundations of conservative political thought in the works of John Locke and Edmund Burke. -

The Aspen Institute Germany ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 the Aspen Institute 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 the Aspen Institute ANNUAL REPORT 2007 3 2008

The Aspen Institute Germany ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 The Aspen Institute 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2008 The Aspen Institute ANNUAL REPORT 2007 3 2008 Dear Friend of the Aspen Institute In the following pages you will find a report on the Aspen Institute Germany’s activities for the years 2007 and 2008. As you may know, the Aspen Institute Germany is a non-partisan, privately supported organization dedicated to values-based leadership in addressing the toughest policy challenges of the day. As you will see from the reports on the Aspen European Strategy Forum, Iran, Syria, Lebanon and the Balkans that follow, a significant part of Aspen’s current work is devoted to promoting dialogue between key stakeholders on the most important strategic issues and to building lasting ties and constructive exchanges between leaders in North America, Europe and the Near East. The reports on the various events that Aspen convened in 2007 and 2008 show how Aspen achieves this: by bringing together interdisciplinary groups of decision makers and experts from business, academia, politics and the arts that might otherwise not meet. These groups are convened in small-scale conferences, seminars and discussion groups to consider complex issues in depth, in the spirit of neutrality and open mindedness needed for a genuine search for common ground and viable solutions. The Aspen Institute organizes a program on leadership development. In the course of 2007 and 2008, this program brought leaders from Germany, Lebanon, the Balkans and the United States of America together to explore the importance of values-based leadership together with one another. -

A Public Debate and Seminar on the 40Th

“CRACKING BORDERS, GROWING WALLS. EUROPEANS FACING THE UKRAINIAN CRISIS” A public debate and seminar on the 40 th anniversary of the declaration of the Helsinki Final Act 8-9 September 2015, Warsaw DRAFT PROGRAMME Tuesday, 8 September 2015 Teatr Polski / Polish Theatre, Warsaw Public debate 16.00 Registration Coffee and refreshments 17.00 Welcome: Jarosław Kuisz, Kultura Liberalna, University of Warsaw, CNRS Paris Michael Thoss, Allianz Kulturstiftung Cornelius Ochmann, Stiftung für deutsch-polnische Zusammenarbeit Antje Contius, Fischer Stiftung 17.15 Opening presentations: Robert Cooper, Special Advisor at the European Commission Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv Jarosław Pietras, General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union 17.40 Panel 1: The current crisis Viola von Cramon, Alliance '90/The Greens Ola Hnatiuk, Polish Academy of Sciences Josef Joffe, publisher-editor of Die Zeit, Hoover Institution, Harvard University Aleksander Smolar, President of Stefan Batory Foundation, CNRS Paris Matt Steinglass, The Economist Chairing : Karolina Wigura, Kultura Liberalna, University of Warsaw, and Katya Gorchinskaya, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna 19.00 Panel 2: Looking into the future of European integration Ulrike Guérot, European Democracy Lab Asle Toje, Norwegian Nobel Institute Roman Kuźniar, former foreign policy advisor to President Bronisław Komorowski Adam Daniel Rotfeld, University of Warsaw, former Poland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Adam Garfinkle, The American -

Conversations with Bill Kristol

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Peter Berkowitz, Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution Taped, March 2, 2018 Table of Contents I: Liberal Democracy and its Critics 0:15 – 39:35 II: Reclaiming the Liberal Tradition 39:35 – 1:04:48 I: Liberal Democracy and its Critics (0:15 – 39:35) KRISTOL: Hi, I’m Bill Kristol, welcome back to CONVERSATIONS. I am joined today by my friend Peter Berkowitz, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, author of many books, articles, fine teacher, formerly at Harvard University – I have to mention that out of pride there – and the author, maybe for the point of this conversation, the one book I guess I might mention is Virtue and the Making of Modern Liberalism, since we are going to talk about liberalism. Liberalism in the broad sense, though: liberal democracy; the liberal tradition, which, we’ll get to this, whether it includes some of modern conservatism, etc. So, liberalism is under assault in a way that maybe we wouldn’t have expected ten, fifteen years ago. Sort of an intellectual, I would say, assault. It seems that way to me. Is that your sense, too? BERKOWITZ: Yes, and it’s a kind of renewed assault, right? Because what we think of as liberalism – and, of course, here I guess we should pause, you kind of gestured at it in the introduction – is what everybody thinks of as “Liberalism” in ordinary political discourse, right? We think of the left wing of the Democratic Party; we think of using government to promote equality, to regulate, to redistribute. -

Anti-Semitism, Anti-Americanism, Anti-Democracy

Nations We Love to Hate: Israel, America and the New Antisemitism* Josef Joffe Classical antisemitism is a fire that has burnt out in the West; this best news in a millennium. Classical, or “operational,” antisemitism was the variant that made Spain and England judenrein for centuries, that led to persecution, expulsion and the Holocaust. Throughout the West, Jews at last have become citizens—and without the kind of assimilation that demanded the sacrifice of identity. And the not-so-good news? During the 2003 World Economic Forum in Davos, a demonstrator wearing the mask of Donald Rumsfeld and an outsized yellow Star of David with “Sheriff” inscribed) was driven forward by a cudgel- wielding likeness of Ariel Sharon, both being followed by a huge rendition of the Golden Calf.1 The message? America is in thrall to the Jews/Israelis, and both are the acolytes of Mammon and the avant-garde of pernicious global capitalism. Let’s call this “conceptual” or “neo-antisemitism.” This variant lacks the eliminationism of the classical type, but it is rife with its most ancient motifs: greed, manipulation, worship of false gods, sheer evil. What is new? It is the projection of old fantasies on two new targets: Israel and America. Indeed, the United States is an antisemitic fantasy come true, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in living color. Don’t Jews, their first loyalty to Israel, control the Congress, the Pentagon, the banks, the universities, and the media? This time, the conspirator is not “World Jewry,” but Israel. Having captured the “hyperpower,” Jews qua Israelis finally do rule the world. -

China After the Pandemic in This Issue Michael R

ISSUE 64 MAY 2020 CHINA AFTER THE PANDEMIC IN THIS ISSUE MICHAEL R. AUSLIN • GORDON G. CHANG • RALPH PETERS EDITORIAL BOARD Victor Davis Hanson, Chair Bruce Thornton David Berkey CONTRIBUTING MEMBERS CONTENTS Peter Berkowitz May 2020 • Issue 64 Josiah Bunting III Angelo M. Codevilla Thomas Donnelly BACKGROUND ESSAY Admiral James O. Ellis Jr. The Coronacrisis Will Simply Exacerbate the Niall Ferguson Geo-strategic Competition between Beijing Chris Gibson and Washington Josef Joffe by Michael R. Auslin Edward N. Luttwak Peter R. Mansoor FEATURED COMMENTARY Walter Russell Mead China Is Flailing in a Post-Coronavirus World Mark Moyar by Gordon G. Chang Williamson Murray Ralph Peters China Lies, China Kills, China Wins Andrew Roberts by Ralph Peters Admiral Gary Roughead Kori Schake EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS Kiron K. Skinner Discussion Questions Barry Strauss Suggestions for Further Reading Bing West Miles Maochun Yu ABOUT THE POSTERS IN THIS ISSUE Documenting the wartime viewpoints and diverse political sentiments of the twentieth century, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives Poster Collection has more than one hundred thousand posters from around the world and continues to grow. Thirty-three thousand are available online. Posters from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Russia/Soviet Union, and France predominate, though posters from more than eighty countries are included. Background Essay | ISSUE 64, May 2020 The Coronacrisis Will Simply Exacerbate the Geo-strategic Competition between Beijing and Washington By Michael R. Auslin Even before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, late last year, the Sino-U.S. relationship had been in a period of flux. Since coming to office in 2017, President Trump made rebalancing ties with China the centerpiece of his foreign policy. -

Political Studies Program, Summer 2015 LEFT & RIGHT in AMERICA

Political Studies Program, Summer 2015 LEFT & RIGHT IN AMERICA Instructors: Peter Berkowitz and James Ceaser Washington, D.C. We continue our study of American politics in the fourth week by taking a close look at the two great rival partisan interpretations of liberal democracy in America. We trace the development of the left from the rise of progressivism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to the implementation of FDR’s New Deal in the second third of the twentieth century, its expansion in LBJ’s Great Society programs, and President Barack Obama’s ambitious domestic agenda designed to further expand government’s reach and responsibilities. To understand the right, we concentrate on the emergence in post-World War II America of several strands of conservative thought—libertarianism, social conservatism, and neoconservatism—and then consider these various strands as they receive expression in the speeches of President Ronald Reagan and President George W. Bush. Tuesday, July 14, 2015, 1:15 pm to 4:15 pm Introduction to Left and Right Readings: • René Descartes, Excerpt from Discourse on Method • Federalist 49 • Selections from Thomas Jefferson • Selections from Edmund Burke • Port Huron Statement, 1962 • Schuette v. Coal, Sotomayor dissent, 2014 Discussion Questions: 1. Why might one want to build or reconstruct society on the basis of reason? 2. Why might one want to respect the organic growth of societies and the wisdom embodied in tradition? 3. In what ways does the Port Huron statement capture the spirit of liberalism? In what ways does it depart from it? 4. How does constitutional government reconcile the claims of reason and tradition? Progressivism Readings: • John Dewey, “My Pedagogic Creed” • Theodore Roosevelt, “Who is a Progressive?” • Woodrow Wilson, “What is Progress?” Right & Left in America – Summer 2015 1 Discussion Questions: 1. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Harvey C. Mansfield Born

1 Curriculum Vitae Harvey C. Mansfield born March 21, 1932; two children; U.S. citizen A.B. Harvard, 1953; Ph.D. Harvard, 1961 Academic Awards: Guggenheim Fellowship, 1970-71 NEH Fellowship, 1974-75 Member, Council of the American Political Science Association, 1980-82, 2004 Fellow, National Humanities Center, 1982 Member, Board of Foreign Scholarships, USIA, 1987-89 Member, Advisory Council, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1991-94 President, New England Political Science Association, 1993-4 Joseph R. Levenson Teaching Award, 1993 The Sidney Hook Memorial Award, 2002 National Humanities Medal, 2004 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, 2007 Present Positions: William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Government, 1993 to date; Carol G. Simon Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University Former Positions: Frank G. Thomson Professor of Government, 1988-93 Professor of Government, 1969-88 Chairman, Department of Government, 1973-77 Associate Professor, Harvard University, 1966-69 Assistant Professor, Harvard University, 1964-66 Lecturer, Harvard University, 1962-64 Assistant Professor, University of California, Berkeley, 1960-62 Office Address: 1737 Cambridge St., Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., 02138 Telephone: 617-495-3333, or 617-495-2148 (department office) Fax: 617-495-0438; email: [email protected] Books: Statesmanship and Party Government, A Study of Burke and Bolingbroke, University of Chicago Press, 1965. The Spirit of Liberalism, Harvard University Press, 1978. Machiavelli's New Modes and Orders: A Study of the Discourses on Livy, Cornell University Press, 1979; reprinted, University of Chicago Press, 2001. 2 Selected Letters of Edmund Burke, edited with an introduction entitled "Burke's Theory of Political Practice," University of Chicago Press, 1984. -

The Role of Academic Discourse in Shaping US-Israel Relations

Archive of SID The Role of Academic Discourse in Shaping US-Israel Relations Mohammad Ali Mousavi Elham Kadkhodaee Abstract Highlighting the need for a more nuanced and multidimensional approach to understanding the relationship between America and Israel, the current article suggests constructivist international relations as a theoretical framework that has the capacity to explain such complexity through the concept of collective identity. According to Alexander Wendt’s version of constructivism, in a Kantian culture of anarchy, states can become friends rather than rivals or enemies, meaning that the security and interests of the Self and Other become identical. In such a situation, a collective identity is formed between the two entities, leading to a friendship that involves not only governments but also the societies, and includes cultural and psychological dimensions as well as geopolitical ones. The current article argues that non-governmental entities such as the academia can play a significant role in constructing such a collective identity. Pro-Israel scholars actively promote a collective identity by producing output that clearly define Israel and America as the Self, and Arabs/Muslims/Palestinians as the Other or the dangerous common enemy. To remain more focused, Holocaust and anti-Semitism are selected as specific fields of study through which formation of the Self/Other dichotomy in academic discourse is studied. A critical discourse analysis of texts authored by Alvin H. Rosenfeld, Andrea Markovits and Josef Joffe will be carried out to demonstrate the themes through which this binary is established. The identification of these themes, and the overall endeavor of pro-Israel scholars to construct American identity in a pro-Israel manner, is necessary for understanding the ideational basis of American relations with Israel.