THE LETTERS of ALCUIN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

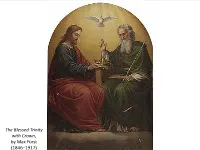

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Francia. Band 44

Francia. Forschungen zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte. Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 44 (2017) Nithard as a Military Historian of the Carolingian Empire, c 833–843 DOI: 10.11588/fr.2017.0.68995 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Bernard S. Bachrach – David S. Bachrach NITHARD AS A MILITARY HISTORIAN OF THE CAROLINGIAN EMPIRE, C 833–843 Introduction Despite the substantially greater volume of sources that provide information about the military affairs of the ninth century as compared to the eighth, the lion’s share of scholarly attention concerning Carolingian military history has been devoted to the reign of Charlemagne, particularly before his imperial coronation in 800, rather than to his descendants1. Indeed, much of the basic work on the sources, that is required to establish how they can be used to answer questions about military matters in the period after Charlemagne, remains to be done. An unfortunate side-effect of this rel- ative neglect of military affairs as well as source criticism for the ninth century has been considerable confusion about the nature and conduct of war in this period2. -

An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems

Discentes Volume 4 Issue 2 Volume 4, Issue 2 Article 4 2016 Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classics Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation . 2016. "Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems." Discentes 4, (2):7-15. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems This article is available in Discentes: https://repository.upenn.edu/discentesjournal/vol4/iss2/4 Poetry Praising Poetry: An Examination of Alcuin's Better-Known Poems Annie Craig, Brown University Alcuin, the 8th century monk, scholar, and advisor to Charlemagne, receives most of his renown from his theological and political essays, as well as from his many surviving letters. During his lifetime he also produced many works of poetry, leaving behind a rich and diverse poetic collection. Carmina 32, 59 and 61 are considered the more famous poems in Alcuin’s collection as they feature all the themes and poetic devices most prominent throughout the poet’s works. While Carmina 32 and 59 address young students Manuscript drawing of Alcuin, ca. 9th century CE. of Alcuin and Carmen 61 addresses a nightingale, all three poems are celebrations of poetry as both a written and spoken medium. This exaltation of poetry accompanies features typical of Alcuin’s other works: the theme of losing touch with a student, the use of classical - especially Virgilian – reference, and an elevation of his message into the Christian world. -

Facts on St Willibrord Patron Saint of Luxembourg &His

FACTS ON ST WILLIBRORD PATRON SAINT OF LUXEMBOURG & HIS CARLOW CONNECTION • St. Willibrord was born near York, Northumbria, England in 658AD. • He died in 739AD aged 81 in Echternach, Luxembourg. • His Feast Day is the 7th of November. • He is the Patron Saint of Luxembourg and he is the only Saint buried in Luxembourg. • He was trained and ordained at a religious site located in the townland of Garryhundon, Co Carlow commonly referred to as Killogan, Rath Melsigi (Rathmelsh) or Clonmelsh. • During the 7th and 8th centuries this site was the most important Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical settlement in Ireland. From 678AD to c. 720AD many Englishmen were trained for the continental mission. • In 690AD Willibrord led a successful mission from Carlow, made up of Irishmen and Englishmen to the continent. • He was consecrated as a Bishop by Pope Sergius 1 in Rome in 695AD. • He built a Cathedral in Utrecht, Holland and became the first Bishop of Utrecht. • In 698AD he established his monastery in Echternach, said to be the oldest town in Luxembourg. • As part of his abbey in Echternach he established a scriptorium where they produced many of the bibles, psalms and prayer-books that are to be found today in the great libraries of Europe. • His signature is the oldest dateable signature in the English language and is written in a book that was probably written in Co. Carlow. This book is now housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. • He is buried in the crypt Basilica of Echternach, Luxembourg which is the centre of his monastery. -

Agobard of Lyon, Empire, and Adoptionism Reusing Heresy to Purify the Faith

Agobard of Lyon, Empire, and Adoptionism Reusing Heresy to Purify the Faith Rutger Kramer Institute for Medieval Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria ABSTRACT — In the late eighth century, the heterodox movement Adoptionism emerged at the edge of the Carolingian realm. Initially, members of the Carolingian court considered it a threat to the ecclesiastical reforms they were spearheading, but they also used the debate against Adoptionism as an opportunity to extend their influence south of the Pyrenees. While they thought the movement had been eradicated around the turn of the ninth century, Archbishop Agobard of Lyon claimed to have found a remnant of this heresy in his diocese several decades later, and decided to alert the imperial court. This article explains some of his motives, and, in the process, reflects on how these early medieval rule-breakers (real or imagined) could be used in various ways by those making the rules: to maintain the purity of Christendom, to enhance the authority of the Empire, or simply to boost one’s career at the Carolingian court. 1 Alan H. Goldman, “Rules and INTRODUCTION Moral Reasoning,” Synthese 117 (1998/1999), 229-50; Jim If some rules are meant to be broken, others are only formulated once their Leitzel, The Political Economy of Rule Evasion and Policy Reform existence satisfies a hitherto unrealized need. Unspoken rules are codified – and (London: Routledge, 2003), 8-23. thereby become institutions – once they have been stretched to their breaking 8 | journal of the lucas graduate conference rutger Kramer point and their existence is considered morally right or advantageous to those in a 2 Alan Segal, “Portnoy’s position to impose them.1 Conversely, the idea that rules can be broken at all rests Complaint and the Sociology of Literature,” The British Journal on the assumption that they reflect some kind of common interest; if unwanted of Sociology 22 (1971), 257-68; rules are simply imposed on a group by an authority, conflict may ensue and be see also Warren C. -

Relations in Earlier Medieval Latin Philosophy: Against the Standard Account

Enrahonar. An International Journal of Theoretical and Practical Reason 61, 2018 41-58 Relations in Earlier Medieval Latin Philosophy: Against the Standard Account John Marenbon Trinity College, Cambridge [email protected] Received: 28-9-2017 Accepted: 16-4-2018 Abstract Medieval philosophers before Ockham are usually said to have treated relations as real, monadic accidents. This “Standard Account” does not, however, fit in with most discus- sions of relations in the Latin tradition from Augustine to the end of the 12th century. Early medieval thinkers minimized or denied the ontological standing of relations, and some, such as John Scottus Eriugena, recognized them as polyadic. They were especially influenced by Boethius’s discussion in his De trinitate, where relations are treated as prime examples of accidents that do not affect their substances. This paper examines non-stand- ard accounts in the period up to c. 1100. Keywords: relations; accidents; substance; Aristotle; Boethius Resum. Les relacions en la filosofia llatina medieval primerenca: contra el relat estàndard Es diu que els filòsofs medievals previs a Occam van tractar les relacions com a accidents reals i monàdics. Però aquest «Relat estàndard» no encaixa amb gran part de les discus- sions que van tenir lloc en la tradició llatina des d’Agustí fins al final del segle xii sobre les relacions. Els primers pensadors medievals van minimitzar o negar l’estatus ontològic de les relacions, i alguns, com Joan Escot Eriúgena, les van reconèixer com a poliàdiques. Aquests filòsofs van estar fonamentalment influïts per la discussió de Boeci en el seu De trinitate, on les relacions es tracten com a primers exemples d’accidents que no afecten les seves substàncies. -

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe Darren Elliot Barber Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies December 2019 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisors, Julia Barrow and William Flynn, for their sincere encouragement and dedication to this project. Heeding their advice early on made this research even more focused, interesting, and enjoyable than I had hoped it would be. The faculty and staff of the Institute for Medieval Studies and the Brotherton Library have been very supportive, and I am grateful to Melanie Brunner and Jonathan Jarrett for their good advice during my semesters of teaching while writing this thesis. I also wish to thank the Reading Room staff of the British Library at Boston Spa for their friendly and professional service. Finally, I would like to thank Jonathan Jarrett and Charles West for conducting such a gracious viva examination for the thesis, and Professor Stephen Alford for kindly hosting the examination. iv Abstract During the Carolingian renewal, Alcuin of York (c. 740–804) played a major role in promoting education for children who would later join the clergy, and encouraging advanced learning among mature clerics. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Thomas Aquinas College Newsletter Fall 2018

quinas A C s o a l Thomas Aquinas College Newsletter m l e o g h e T Fall 2018 Volume 46, Issue 3 1971 Eastward Bound! College Receives Approval for New England Campus ulminating a rigorous process that campus and, thanks be to God, that day Cbegan in the spring of 2017, Thomas has arrived.” Aquinas College has received approval Notably, the College’s need for expan- from the Massachusetts Board of Higher sion counters a 50-year trend in higher Education to operate a branch campus education, in which more than a quarter in Western Massachusetts, where it will of the country’s small liberal arts schools award the degree of Bachelor of Arts in have either closed, merged, or abandoned Liberal Arts. The decision sets the stage their missions. “At a time when more for Thomas Aquinas College, New Eng- than a few liberal arts colleges have had land, to open its doors in fall 2019. to close,” says R. Scott Turicchi, chairman The Board’s approval comes as the of the College’s Board of Governors, “it is result of a thorough and rigorous appli- a testament to the excellence of Thomas cation process conducted by its legal Aquinas College’s unique program of and academic affairs staff at the Massa- Catholic liberal education and to its good chusetts Department of Higher Educa- stewardship that the school has received tion. Its grant of authority is subject to school in Northfield, Massachusetts, course, friends’ donations to cover the approval to operate a second campus.” stipulations, the most important of which which has been shuttered since 2005. -

Prudentius of Troyes (D. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era

Prudentius of Troyes (d. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era by Jared G. Wielfaert A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Jared Wielfaert 2015 Prudentius of Troyes (d. 861) and the Reception of the Patristic Tradition in the Carolingian Era Jared Gardner Wielfaert Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2015 ABSTRACT: This study concerns Prudentius, bishop of Troyes (861), a court scholar, historian, and pastor of the ninth century, whose extant corpus, though relatively extensive, remains unstudied. Born in Spain in the decades following the Frankish conquest of the Spanish march, Prudentius had been recruited to the Carolingian court under Louis the Pious, where he served as a palace chaplain for a twenty year period, before his eventual elevation to the see of Troyes in the 840s. With a career that moved from the frontier to the imperial court center, then back to the local world of the diocese and environment of cathedral libraries, sacred shrines, and local care of souls, the biography of Prudentius provides a frame for synthesis of several prevailing currents in the cultural history of the Carolingian era. His personal connections make him a rare link between the generation of the architects of the Carolingian reforms (Theodulf and Alcuin) and their students (Rabanus Maurus, Prudentius himself) and the great period of fruition of which the work of John Scottus Eriugena is the most widely recogized example. His involvement in the mid-century theological controversy over the doctrine of predestination illustrates the techniques and methods, as well as the concerns and preoccupations, of Carolingian era scholars engaged in the consolidation and interpretation of patristic opinion, particularly, that of Augustine.