Irina Liebmann Und Der Doppelgänger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISUM #3, Per10d Ending 142400 Dec 61

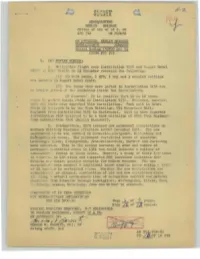

, 6-2.. • S'=I'R..."'~ ET. HEAIlQUARTElIS BERLIN BRIGADE Off ice of the AC of 8, G2 APO 742 US FOR::ES + 1 . (8 \ ~!l..'ClE1' FORCES: a. Hf'llccpter f light over Installation 4154 and AUf,J'1..lst Bebel PIa t."':t.:1 E.l.f"t Ber::'ln on 13 December revealed the following: (1) 29 T-S4 tanks , 1 BTR ~ 1 bus and 3 wheeled vehicles are lonat;u 1n August Ecbel Platz. (2) Tho tanks that were parked 1n Installation 4154 are n':) 10n3C'r jX.rkC'd oJ!" th::! hardstand inside the in::>tall at:'..on . 02 C:nlr.l.Cnt: It 1s possible thf'.t 10 to 12 tunI.s w'uld b,- p~.~'·:(r0. inside ::::h3ds 1n Insullatlon 415 1~ . Br;1 l.icved, ho~·e"E.r, thE'.t fO.ll tt.rks h'we dep.-,rtcd this installation. Tank unit in Bebel Platz 1s b_'1.i8ved to be Jchc Tt..nk Battalion, 83d Motorized Riflo il0giment fr.i:n Installation 4161 1n Karlshorst. Un! t to have departed IlStnllatl~n 4154 believe d to be a tank battalion of 68th Tnnk Regiment f rom InstallE:.tion 4102 (Berl~n Blesdorf). b . Headquarters, GSfo'G imposed new permanent 1'cstrictions on Wcs.tern Mili t:-", ry Missions effective 12000:1. December 1961. The new restrictcd c.r .m,s are located in Schwerin-~udwiglust, W:Ltt.3nburg and Ko·~igsb ru ,ck areas. The permanent r es tric ted areas of Guestrow; Letzlingcr lI~ide . Altengrabow. Jena-Weissenfe1s, Ohrdrv.f and Juetcl'bog were exten,Ld. -

The Rhetorical Crisis of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

THE RHETORICAL CRISIS OF THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL: FORGOTTEN NARRATIVES AND POLITICAL DIRECTIONS A Dissertation by MARCO EHRL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Nathan Crick Committee Members, Alan Kluver William T. Coombs Gabriela Thornton Head of Department, J. Kevin Barge August 2018 Major Subject: Communication Copyright 2018 Marco Ehrl ABSTRACT The accidental opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, dismantled the political narratives of the East and the West and opened up a rhetorical arena for political narrators like the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German leadership to define and exploit the political crisis and put forward favorable resolutions. With this dissertation, I trace the neglected and forgotten political directions as they reside in the narratives of the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German political leadership between November 1989 and February 1990. The events surrounding November 9th, 1989, present a unique opportunity for this endeavor in that the common flows of political communication between organized East German publics, the West German press, and West German political leaders changed for a moment and with it the distribution of political legitimacy. To account for these new flows of political communication and the battle between different political crisis narrators over the rhetorical rights to reestablish political legitimacy, I develop a rhetorical model for political crisis narrative. This theoretical model integrates insights from political crisis communication theories, strategic narratives, and rhetoric. -

The Fall of the Wall: the Unintended Self-Dissolution of East Germany’S Ruling Regime

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN, ISSUE 12 /13 131 The Fall of the Wall: The Unintended Self-Dissolution of East Germany’s Ruling Regime By Hans-Hermann Hertle ast Germany’s sudden collapse like a house of cards retrospect to have been inevitable.” He labeled this in fall 1989 caught both the political and academic thinking “whatever happened, had to have happened,” or, Eworlds by surprise.1 The decisive moment of the more ironically, “the marvelous advantage which historians collapse was undoubtedly the fall of the Berlin Wall during have over political scientists.”15 Resistance scholar Peter the night of 9 November 1989. After the initial political Steinbach commented that historians occasionally forget upheavals in Poland and Hungary, it served as the turning very quickly “that they are only able to offer insightful point for the revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe and interpretations of the changes because they know how accelerated the deterioration of the Soviet empire. Indeed, unpredictable circumstances have resolved themselves.”16 the Soviet Union collapsed within two years. Along with In the case of 9 November 1989, reconstruction of the the demolition of the “Iron Curtain” in May and the details graphically demonstrates that history is an open opening of the border between Hungary and Austria for process. In addition, it also leads to the paradoxical GDR citizens in September 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall realization that the details of central historical events can stands as a symbol of the end of the Cold War,2 the end of only be understood when they are placed in their historical the division of Germany and of the continent of Europe.3 context, thereby losing their sense of predetermination.17 Political events of this magnitude have always been The mistaken conclusion of what Reinhard Bendix the preferred stuff of which legends and myths are made of. -

Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989

The Berlin Wall was the 97-mile-long physical barrier that separated the city of West Berlin from East Berlin and the rest of East Germany from 1961 until the East German government relaxed border controls in November 1989. The 13-foot-high concrete wall snaked through Berlin, effectively sealing off West Berlin from ground access except for through heavily guarded checkpoints. It included guard towers and a wide area known as the “death strip” that contained anti-vehicle trenches, barbed wire, and other defenses. The wall came to symbolize the “Iron Curtain” that separated Western Europe and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. As East Germany grew more socialist in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, about 3.5 million East Germans fled from East Berlin into democratic West Berlin. From there, they could then travel to West Germany and other Western European countries. It became clear to the powers of East Germany that they might not survive as a state with open borders to the West. Between 1961 and 1989, the wall prevented almost all such emigration. Among the many attempt to escape included through underground tunnels, hot-air balloons, and with the support of organized groups of Fluchthelfer (flight helpers). The East German border guards’ shoot-to-kill order against refugees resulted in about 250-300 deaths between August 1961, and February 1989. Demonstrations and protests in the late 1980’s began to build stress on the East German government to open the city. In the summer of 1989, neighboring Hungary opened its border and thousands of East Germans fled the communist country for the West. -

Marking the 20Th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall Responsible Leadership in a Globalized World

A publication of the Contributors include: President Barack Obama | James L. Jones Chuck Hagel | Horst Teltschik | Condoleezza Rice | Zbigniew Brzezinski [ Helmut Kohl | Colin Powell | Frederick Forsyth | Brent Scowcroft ] Freedom’s Challenge Marking the 20th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall Responsible Leadership in a Globalized World The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, not only years, there have been differences in opinion on important led to the unifi cation of Germany, thus ending decades of issues, but the shared interests continue to predominate. division and immeasurable human suffering; it also ended It is important that, in the future, we do not forget what binds the division of Europe and changed the world. us together and that we defi ne our common interests and responsibilities. The deepening of personal relations between Today, twenty years after this event, we are in a position to young Germans and Americans in particular should be dear gauge which distance we have covered since. We are able to to our hearts. observe that in spite of continuing problems and justifi ed as well as unjustifi ed complaints, the unifi cation of Germany and For this reason the BMW Foundation accounts the Europe has been crowned with success. transatlantic relationship as a focus of its activity. The Transatlantic Forum for example is the “veteran“ of the It is being emphasized again and again, and rightly so, that it BMW Foundation’s Young Leaders Forums. The aim of was the people in the former GDR that started the peaceful these Young Leaders Forums is to establish a network, revolution. -

Berlin Visit Focus Berlinhistory

BERLIN / EAST BERLIN HISTORY Berlin House of Representatives (Abgeordnetenhaus) Niederkirchnerstraße 5, 10117 Berlin Contact: +49 (0) 30 23250 Internet: https://www.parlament-berlin.de/de/English The Berlin House of Representatives stands near the site of the former Berlin Wall, and today finds itself in the center of the reunified city. The president directs and coordinates the work of the House of Representatives, assisted by the presidium and the Council of Elders, which he or she chairs. Together with the Martin Gropius Bau, the Topography of Terror, and the Bundesrat, it presents an arresting contrast to the flair of the new Potsdamer Platz. (source: https://www.parlament-berlin.de/de/English) FHXB Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg museum Adalbertstraße 95A, 10999 Berlin Contact: +49 (0)30 50 58 52 33 Internet: https://www.fhxb-museum.de The intricate web of different experiences of history, lifestyles, and ways of life; the coexistence of different cultures and nationalities in tight spaces; contradictions and fissures: These elements make the Berlin district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg compelling – and not only to those interested in history. The Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum documents the history of this district. It emerged from the fusion of the districts of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg with the merger of the Kreuzberg Museum with the Heimatmuseum Friedrichshain. In 1978, the Kreuzberg Office for the Arts began to develop a new type of local museum, in which everyday history – a seemingly banal relic – and the larger significance -

1 Ulbricht's Berlin Problem

c01.qxd 1/7/04 2:51 PM Page 5 1 Ulbricht’s Berlin Problem Early in the year in which John F. Kennedy became presi- dent of the United States, apprehension about Soviet for- eign policy was high. Nikita Khrushchev was in power, and his rhetoric was threatening. Historians looking back on the crisis centering on Berlin, 1961, now mostly agree that it was not on the scale of what would come one year later over Soviet missiles in Cuba, but at the time, Khrushchev’s claims, and the bellicose language he used in pressing them, made it sound as if World War III were imminent. The threat by the noisy first secretary, boss of the Soviet Union and of the Eastern European Communist world, was that he was prepared to write a separate peace treaty with East Germany. The situation Khrushchev was exploit- ing was the result of what Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt had agreed upon at Yalta in February 1945. What they had done there was confirmed and embellished at the Potsdam conference in July and August 1945 and expanded in sub- agreements over the ensuing months. The design was to invest formal authority over Germany in the victorious pow- ers: Soviet, British, and American. To their number France 5 c01.qxd 1/7/04 2:51 PM Page 6 6 THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL was added, with the war’s end, something of a collegial gesture by Britain and the United States. These powers would jointly govern Germany and, within it, Berlin. For administrative purposes, Germany was divided into four zones, Berlin into four sectors, each assigned to one of the occupying powers. -

Stetler on Paeslack, 'Constructing Imperial Berlin: Photography and the Metropolis'

H-Urban Stetler on Paeslack, 'Constructing Imperial Berlin: Photography and the Metropolis' Review published on Wednesday, November 13, 2019 Miriam Paeslack. Constructing Imperial Berlin: Photography and the Metropolis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019. 216 pp. $30.00 (paper), ISBN 978-1-5179-0295-7. Reviewed by Pepper Stetler (Miami University of Ohio) Published on H-Urban (November, 2019) Commissioned by Alexander Vari (Marywood University) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54356 In 2008 the Palast der Republik, an architectural showpiece of the former East Berlin, was demolished to make way for the reincarnation of an eighteenth-century palace that once stood in the same place. The new old building aims to serve as the cultural center of a city already rich with fraught monuments to contested histories. According to the project’s official website, the palace will revive the “authentic orientation” of surrounding monuments and the nearby Unter den Linden, an elegant nineteenth-century boulevard now overrun with tourist shops and a wax museum. The website does not mention how this historicist assertion might disorient other buildings from Berlin’s history, such as the nearby television tower and the Tränenpalast (Palace of Tears), which was a border crossing between East and West Berlin and the site of too many separations of friends and family during the Cold War. Certain parts of history are worth remembering (and commercializing), while others, it seems, are erased. Miriam Paeslack only briefly refers to the second life of Berlin’s palace in her study,Constructing Imperial Berlin: Photography and the Metropolis. -

Cold War to the Building of the Two Opposed Blocs of Western and Eastern Europe Down to the Mid-1960S

Ian Kershaw - Europe, 1950–2017 Contents List of Illustrations List of Maps Map Preface Foreword: Europe’s Two Eras of Insecurity 1. The Tense Divide 2. The Making of Western Europe 3. The Clamp 4. Good Times 5. Culture after the Catastrophe 6. Challenges 7. The Turn 8. Easterly Wind of Change 9. Power of the People 10. New Beginnings 11. Global Exposure 12. Crisis Years Afterword: A New Era of Insecurity Illustrations Bibliography Acknowledgements Follow Penguin THE PENGUIN HISTORY OF EUROPE General Editor: David Cannadine I. SIMON PRICE AND PETER THONEMANN: The Birth of Classical Europe: A History from Troy to Augustine* II. CHRIS WICKHAM: The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000* III. WILLIAM JORDAN: Europe in the High Middle Ages* IV. ANTHONY GRAFTON: Renaissance Europe V. MARK GREENGRASS: Christendom Destroyed: Europe 1517–1648* VI. TIM BLANNING: The Pursuit of Glory: Europe 1648–1815* VII: RICHARD J. EVANS: The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815–1914* VIII. IAN KERSHAW: To Hell and Back: Europe 1914–1949* IX. IAN KERSHAW: Roller-Coaster: Europe 1950–2017* *already published List of Illustrations 1. The Aldermaston march, April 1958 (Bentley Archive/Popperfoto/Getty Images) 2. Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, 1953 (PhotoQuest/Getty Images) 3. Konrad Adenanauer and Robert Schuman, 1951 (AFP/Getty Images) 4. Crowds at Stalin’s funeral, 1953 (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images) 5. President Tito and Nikita Khrushchev in Belgade, 1963 (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 6. Soviet tank destroyed in the Hungarian uprising of 1956 (Sovfoto/UIG/Getty Images) 7. Algerian Harkis arriving in France, 1962 (STF/AFP/Getty Images) 8. -

GERMANY 1960-January 1963

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files GERMANY 1960-January 1963 Internal Affairs and Foreign Affairs Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files GERMANY 1960-January 1963 INTERNAL AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 762, 862, and 962 and FOREIGN AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 662 and 611.62 Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide Compiled by Dan Elasky Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Germany, 1960-January 1963 [microform] : internal affairs and foreign affairs / [project coordinator, Robert E. Lester]. microfilm reels. Accompanied by a printed guide entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Germany 1960-January 1963. ISBN 1-55655-750-7 1. Germany--History--1945-1990--Sources. 2. United States. Dept. of State--Archives. I. Title: Germany, 1960-January 1963. II. Lester, Robert. III. United States. Dept. of State. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Germany 1960-January 1963. DD257 943.087--dc21 2002066164 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States. No copyright is claimed in these official records. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Scope and Content Note vii Source Note ix Organization of the U.S. Department of State Decimal Filing System xi Numerical List of Country -

Cold War Stations Station A: Berlin Airlift Your Task 1

Cold War Stations Station A: Berlin Airlift Your Task 1. Read the description of the Berlin Airlift. 2. Examine the pictures and map of the Airlift. Write your observations about pictures. 3. Then, look at Cartoon A and Cartoon B: A. What is the artistic purpose in these two cartoons? B. What do you think the artist thought about the Berlin airlift in these cartoons? C. Do you think that this feeling is similar to the opinion of the rest of America? Why or Why not? D. Which cartoon do you think is more accurate? Why? Station A: Berlin Airlift (background) The Berlin airlift marked the first major confrontation in the Cold War. For 11 months, beginning in June 1948, the Western allies took part in an unprecedented attempt to keep a city alive -- entirely from the air. Following World War II, Germany is divided into four zones of occupation -- Soviet, British, French and American. Germany, and Berlin in particular, are the only places where communist and capitalist forces come into direct contact. In June 1948, an announcement by the Western Allies brings a crisis to Berlin. They establish a currency reform meant to wipe out the German black market and further tie the vulnerable German economy to the West. The Soviets are not told and are infuriated by the action. On Thursday, June 24, 1948, West Berlin wakes to find itself under a Soviet blockade -- and in the midst of the first major confrontation of the Cold War. The Western Allies impose a counter-blockade on the Soviet zone. -

The Berlin Wall: History at a Glance History – Testimonies – Relics

The Berlin Wall: History at a Glance Please note: For the respective openings and closings as well as the special protective measures during the pandemic, check the websites of the museums and memorials. History – Testimonies – Relics © Landesarchiv Berlin Checkpoint Charlie, 1961 For more than 28 years East and West Berlin were divided by an almost insurmountable Wall. Not only did it divide families and friends but it also brought much pain and suffering to the city. At least 136 people lost their lives here, mostly when attempting to flee from East to West. The joy which accompanied the fall of the wall on 9th November 1989 generated a feeling of euphoria in which the majority of border posts disappeared. There are only a few original relics left. The following round-up is intended to help with the search for evidence. In addition, it will provide an insight into the history of the Wall and highlight the dramatic events that took place on 9th November 1989. The Wall – the Background up to its Construction in 1961 As early as during the course of the Second World War the Allies had resolved to divide Germany, once defeated, into occupation zones and allow the country to be administered by the victorious powers, that is, the USA, Great Britain and the USSR. France only came on board as the fourth occupying power after the Yalta Conference in February 1945. At the Conference held in Potsdam at the beginning of August 1945, the victorious powers approved the four zones and the four sectors of Berlin, the eastern boundary along the Oder Neiße line as well as the economic unit of Germany.