Frontier of Freedom: Berlin in American Cold War Discourse from the Airlift to Kennedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violence and the Word

Essays Violence and the Word Robert M. Coverf I. INTRODUCTION: THE VIOLENCE OF LEGAL ACTS Legal interpretation' takes place in a field of pain and death. This is true in several senses. Legal interpretive acts signal and occasion the im- position of violence upon others: A judge articulates her understanding of a text, and as a result, somebody loses his freedom, his property, his chil- dren, even his life. Interpretations in law also constitute justifications for violence which has already occurred or which is about to occur. When interpreters have finished their work, they frequently leave behind victims whose lives have been torn apart by these organized, social practices of violence. Neither legal interpretation nor the violence it occasions may be properly understood apart from one another. This much is obvious, though the growing literature that argues for the centrality of interpretive practices in law blithely ignores it.2 t Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University. There are always legends of those who came first, who called things by their right names and thus founded the culture of meaning into which we latecomers are born. Charles Black has been such a legend, striding across the landscape of law naming things, speaking "with authority." And we who come after him are eternally grateful. I wish to thank Harlon Dalton, Susan Koniak and Harry Wellington for having read and com- mented upon drafts of this essay. Some of the ideas in this essay were developed earlier, in the Brown Lecture which I delivered at the Georgia School of Law Conference on Interpretation in March, 1986. -

CBU Student Handbook

DELIVERY OF INSTRUCTION California Baptist University expects to deliver instruction to its students through its traditional in-person and online formats. By attending the University, students acknowledge this expectation and understand that the University may be compelled to modify course instruction formats due to circumstances or events beyond the University’s reasonable control such as acts of God, acts of government, war, disease, social unrest, and accidents. As such, students attending the University assume the risk that circumstances may arise that mandate the closure of the campus or place restrictions upon the University’s delivery of instruction. By attending the University, each student understands and agrees that they will not be entitled to a refund or price adjustment for the cost of course instruction if their courses are required to be provided in a modified format which the University deems appropriate under such circumstances. 2021-2022 Student Handbook i California Baptist University | 09.24.21 TABLE OF CONTENTS Delivery of Instruction .................................................................................................................................................................................... i Personnel Directory ....................................................................................................................................................................................... ix Administration .................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

1956 Counter-Revolution in Hungary - Words and Weapons

Janos Berecz 1956 Counter-Revolution in Hungary - Words and Weapons - Akademiai Kiado, Budapest 1986 Translated from the second, enlarged and revised edition of Ellenforradalom tollal es fegyverrel 1956. Published by Kossuth Konyvkiado, Budapest, 1981 Translated by Istvan Butykay Translation revised by Charles Coutts ISBN 963 05 4370 2 © Akademiai Kiado, Budapest 1986 Printed in Hungary Contents Preface 7 Chapter 1. Hungary and the International Situation before 1956 9 Chapter 2. The Doctrines of "Containment" and "Libera tion "—Political Warfare (1947-1954) 14 Chapter 3. The First Phase of Operation FOCUS (1954-1955) 25 3.1. The Beginnings of Intervention 25 3.2. The Internal Situation of Hungary 32 3.3. Attack Launched by the External Enemy 43 3.4. Reactivating the Internal Enemy 48 Chapter4. The Second Phase of Operation FOCUS (1956).... 58 4.1. The Bankruptcy of the Dogmatic Leadership of the Party 58 4.2. The Group of Imre Nagy Organizes Itself into Party Opposition 63 4.3. Preparations for a Coordinated Attack 71 4.4. The Situation before the Explosion 77 4.5. The Eve of the Counter-Revolution 83 Chapter 5. The Socialist Forces against Counter-Revolution- ary Revolt and Treachery (From October 23 to November 4,1956) 97 5 5.1. The Preparation of the Demonstration 97 5.2. The First Phase of the Armed Revolt 103 5.3. The Struggle Waged by the Forces Loyal to Socialism 114 5.4. Imre Nagy and Radio Free Europe Call for the With drawal of Soviet Troops 130 5.5. The Second Phase of the Counter-Revolution: Resto ration and "Neutrality" 137 5.6. -

The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications Communication, College of 9-1-2018 The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965 Gregory R. Olson Marquette University George N. Dionisopoulos San Diego State University Steven R. Goldzwig Marquette University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/comm_fac Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Gregory R.; Dionisopoulos, George N.; and Goldzwig, Steven R., "The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965" (2018). College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications. 511. https://epublications.marquette.edu/comm_fac/511 The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945–1965 Gregory A. Olson, George N. Dionisopoulos, and Steven R. Goldzwig 8 I do not believe that any of the Presidents who have been involved with Viet- nam, Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, or President Nixon, foresaw or desired that the United States would become involved in a large scale war in Asia. But the fact remains that a steady progression of small decisions and actions over a period of 20 years had forestalled a clear-cut decision by the President or by the President and Congress—decision as to whether the defense of South Vietnam and involvement in a great war were necessary to the security and best interest of the United States. —Senator John Sherman Cooper (R-KY), Congressional Record, 1970 n his 1987 doctoral thesis, General David Petraeus wrote of Vietnam: “We do not take the time to understand the nature of the society in which we are f ght- Iing, the government we are supporting, or the enemy we are f ghting.”1 After World War II, when the United States chose Vietnam as an area for nation building as part of its Cold War strategy, little was known about that exotic land. -

George Seaton Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

George Seaton 电影 串行 (大全) 36 Hours https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/36-hours-227532/actors Chicken Every https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/chicken-every-sunday-2963389/actors Sunday What's So Bad About https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/what%27s-so-bad-about-feeling-good%3F-3204274/actors Feeling Good? Little Boy Lost https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-boy-lost-3225457/actors Showdown https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/showdown-3282975/actors For Heaven's Sake https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/for-heaven%27s-sake-3352342/actors Anything Can https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/anything-can-happen-4000927/actors Happen Where Do We Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/where-do-we-go-from-here%3F-4244332/actors from Here? Apartment for Peggy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/apartment-for-peggy-4779186/actors The Big Lift https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-big-lift-495924/actors Diamond Horseshoe https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/diamond-horseshoe-5270833/actors The Hook https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-hook-562304/actors Junior Miss https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/junior-miss-6313371/actors Williamsburg: the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/williamsburg%3A-the-story-of-a-patriot-8021151/actors Story of a Patriot The Counterfeit https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-counterfeit-traitor-908713/actors Traitor 蓬門淑女 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E8%93%AC%E9%96%80%E6%B7%91%E5%A5%B3-1305029/actors -

Berlin by Sustainable Transport

WWW.GERMAN-SUSTAINABLE-MOBILITY.DE Discover Berlin by Sustainable Transport THE SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT GUIDE GERMANY The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) serves as a guide for sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions from Germany. As a platform for exchanging knowledge, expertise and experiences, GPSM supports the transformation towards sustainability worldwide. It serves as a network of information from academia, businesses, civil society and associations. The GPSM supports the implementation of sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions in a comprehensive manner. In cooperation with various stakeholders from economic, scientific and societal backgrounds, the broad range of possible concepts, measures and technologies in the transport sector can be explored and prepared for implementation. The GPSM is a reliable and inspiring network that offers access to expert knowledge, as well as networking formats. The GPSM is comprised of more than 150 reputable stakeholders in Germany. The GPSM is part of Germany’s aspiration to be a trailblazer in progressive climate policy, and in follow-up to the Rio+20 process, to lead other international forums on sustainable development as well as in European integration. Integrity and respect are core principles of our partnership values and mission. The transferability of concepts and ideas hinges upon respecting local and regional diversity, skillsets and experien- ces, as well as acknowledging their unique constraints. www.german-sustainable-mobility.de Discover Berlin by Sustainable Transport This guide to Berlin’s intermodal transportation system leads you from the main train station to the transport hub of Alexanderplatz, to the redeveloped Potsdamer Platz with its high-qua- lity architecture before ending the tour in the trendy borough of Kreuzberg. -

Escape to Freedom: a Story of One Teenager’S Attempt to Get Across the Berlin Wall

Escape to Freedom: A story of one teenager’s attempt to get across the Berlin Wall By Kristin Lewis From the April 2019 SCOPE Issue Every muscle in Hartmut Richter’s body ached. He’d been in the cold water for four agonizing hours. His body temperature had plummeted dangerously low. Now, to his horror, he found himself trapped in the water by a wall of razor-sharp barbed wire. Precious seconds ticked by. The area was crawling with guards carrying machine guns. Some had snarling dogs at their sides. If they caught Hartmut, he could be thrown in prison—or worse. These men were trained to shoot on sight. Hartmut grabbed the wire with his bare hands. He began pulling it apart, hoping he could make a hole large enough to squeeze through. Hartmut Richter was not a criminal escaping from jail. He was not a bank robber on the run. He was simply an 18-year-old kid who wanted nothing more than to be free—to listen to the music he wanted to listen to, to say what he wanted to say and think what he wanted to think. And right now, Hartmut was risking everything to escape from his country and start a new life. A Bleak Time Hartmut was born in Germany in 1948. He lived near the capital city of Berlin with his parents and younger sister. This was a bleak time for his country. Only three years earlier, Germany had been defeated in World War II. During the war, Germany had invaded nearly every other country in Europe. -

Tageszeitung (Taz) Article on the Opening of the Berlin Wall

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) Two journalists from Die Tageszeitung (taz), a left-of-center West Berlin newspaper, describe the excitement generated by the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. The event was the result of internal pressure applied by East German citizens, and it evoked spontaneous celebration from a people who could once again freely cross the border and rekindle relationships with friends and relatives on the other side. (Please note: the dancing bear mentioned below is a figurative reference to West Berlin's official mascot. Beginning in 1954, the flag of West Berlin featured a red bear set against a white background. In 1990, the bear became the mascot of a unified Berlin. The former West Berlin flag now represents the city as a whole.) "We Want In!" The Bear Is Dancing on the Border Around midnight, RIAS – the American radio station broadcasting to the East – still has no traffic interruptions to report. Yet total chaos already reigns at the border checkpoint on Invalidenstrasse. People parked their cars at all conceivable angles, jumped out, and ran to the border. The transmission tower of the radio station "Free Berlin" is already engulfed by a throng of people (from the West) – waiting for the masses (from the East) to break through. After three seconds, even the most hardened taz editor finds himself applauding the first Trabi he sees. Everyone gets caught up in the frenzy, whether she wants to or not. Even the soberest members of the crowd are applauding, shrieking, gasping, giggling. -

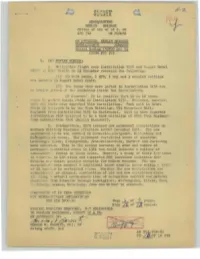

ISUM #3, Per10d Ending 142400 Dec 61

, 6-2.. • S'=I'R..."'~ ET. HEAIlQUARTElIS BERLIN BRIGADE Off ice of the AC of 8, G2 APO 742 US FOR::ES + 1 . (8 \ ~!l..'ClE1' FORCES: a. Hf'llccpter f light over Installation 4154 and AUf,J'1..lst Bebel PIa t."':t.:1 E.l.f"t Ber::'ln on 13 December revealed the following: (1) 29 T-S4 tanks , 1 BTR ~ 1 bus and 3 wheeled vehicles are lonat;u 1n August Ecbel Platz. (2) Tho tanks that were parked 1n Installation 4154 are n':) 10n3C'r jX.rkC'd oJ!" th::! hardstand inside the in::>tall at:'..on . 02 C:nlr.l.Cnt: It 1s possible thf'.t 10 to 12 tunI.s w'uld b,- p~.~'·:(r0. inside ::::h3ds 1n Insullatlon 415 1~ . Br;1 l.icved, ho~·e"E.r, thE'.t fO.ll tt.rks h'we dep.-,rtcd this installation. Tank unit in Bebel Platz 1s b_'1.i8ved to be Jchc Tt..nk Battalion, 83d Motorized Riflo il0giment fr.i:n Installation 4161 1n Karlshorst. Un! t to have departed IlStnllatl~n 4154 believe d to be a tank battalion of 68th Tnnk Regiment f rom InstallE:.tion 4102 (Berl~n Blesdorf). b . Headquarters, GSfo'G imposed new permanent 1'cstrictions on Wcs.tern Mili t:-", ry Missions effective 12000:1. December 1961. The new restrictcd c.r .m,s are located in Schwerin-~udwiglust, W:Ltt.3nburg and Ko·~igsb ru ,ck areas. The permanent r es tric ted areas of Guestrow; Letzlingcr lI~ide . Altengrabow. Jena-Weissenfe1s, Ohrdrv.f and Juetcl'bog were exten,Ld. -

Irina Liebmann Und Der Doppelgänger

https://doi.org/10.25620/ci-03_13 CATHERINE SMALE »Wir sind wie Spiegel« Irina Liebmann und der Doppelgänger ZITIERVORGABE: Catherine Smale, »»Wir sind wie Spiegel«: Irina Liebmann und der Doppelgänger«, in Phantasmata: Techniken des Unheimlichen, hg. v. Martin Doll, Rupert Gaderer, Fabio Camilletti und Jan Niklas Howe, Cultural Inquiry, 3 (Wien: Turia + Kant, 2011), S. 203–17 <https: //doi.org/10.25620/ci-03_13> ANGABE ZU DEN RECHTEN: Phantasmata: Techniken des Unheimlichen, hg. © by the author(s) v. Martin Doll, Rupert Gaderer, Fabio Camil- This version is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- letti und Jan Niklas Howe, Cultural Inquiry, 3 ShareAlike 4.0 International License. (Wien: Turia + Kant, 2011), S. 203–17 SCHLAGWÖRTER: Freud, Sigmund – Das Unheimliche; Psychoanalyse; Doppelgänger (Motiv); Liebmann, Irina – Die freien Frauen; Liebmann, Irina – In Berlin; Berliner Mauer (Motiv); Deutschland (Motiv) / Teilung (Motiv); Spiegelung (Motiv); Mise en abyme The ICI Berlin Repository is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the dissemination of scientific research documents related to the ICI Berlin, whether they are originally published by ICI Berlin or elsewhere. Unless noted otherwise, the documents are made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.o International License, which means that you are free to share and adapt the material, provided you give appropriate credit, indicate any changes, and distribute under the same license. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ for further details. In particular, you should indicate all the information contained in the cite-as section above. ¨8*34*/%8*&41*&(&-§ *SJOB-JFCNBOOVOEEFS%PQQFMHjOHFS1 $BUIFSJOF4NBMF If the story of the ›Doppelgänger‹ has to break off here for the purposes of this book, it is certainly not finished yet. -

Traction Invitation to the 129Th Annual General

Invitation to the 129th Annual General Meeting of AUDI AG at 10.00 a.m. on May 9, 2018, at the Audi Forum Ingolstadt traction AUDI GROUP KEY FIGURES 2017 2016 Change in % Production Automotive segment Cars 1) 1,879,840 1,903,259 – 1.2 Engines 1,966,434 1,927,838 2.0 Motorcycles segment Motorcycles 56,743 56,978 – 0.4 Deliveries to customers Automotive segment Cars 2,105,084 2,088,187 0.8 Audi brand 2) Cars 1,878,105 1,867,738 0.6 Lamborghini brand Cars 3,815 3,457 10.4 Other Volkswagen Group brands Cars 223,164 216,992 2.8 Motorcycles segment Motorcycles 55,871 55,451 0.8 Ducati brand Motorcycles 55,871 55,451 0.8 Workforce Average 90,402 87,112 3.8 Revenue EUR million 60,128 59,317 1.4 Operating profit before special items EUR million 5,058 4,846 4.4 Operating profit EUR million 4,671 3,052 53.0 Profit before tax EUR million 4,783 3,047 57.0 Profit after tax EUR million 3,479 2,066 68.4 Operating return on sales before special items Percent 8.4 8.2 Operating return on sales Percent 7.8 5.1 Return on sales before tax Percent 8.0 5.1 Return on investment (ROI) Percent 14.4 10.7 Ratio of capex 3) Percent 6.4 5.7 Research and development ratio Percent 6.3 7.5 Cash flow from operating activities EUR million 6,173 7,517 – 17.9 Net cash flow 4) EUR million 4,312 2,094 105.9 Balance sheet total (Dec. -

Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900

"/v9 6a~ts1 HEINRICH ZILLE'S BERLIN SELECTED THEMES FROM 1900 TO 1914: THE TRIUMPH OF 'ART FROM THE GUTTER' THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Catherine Simke Nordstrom Denton, Texas May, 1985 Copyright by Catherine Simke Nordstrom 1985 Nordstrom, Catherine Simke, Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900 to 1914: The Trium of 'Art from the Gutter.' Master of Arts (Art History), May, 1985, 139 pp., 71 illustrations, bibliography, 64 titles. Heinrich Zille (1858-1929), an artist whose creative vision was concentrated on Berlin's working class, portrayed urban life with devastating accuracy and earthy humor. His direct and often crude rendering linked his drawings and prints with other artists who avoided sentimentality and idealization in their works. In fact, Zille first exhibited with the Berlin Secession in 1901, only months after Kaiser Wilhelm II denounced such art as Rinnsteinkunst, or 'art from the gutter.' Zille chose such themes as the resultant effects of over-crowded, unhealthy living conditions, the dissolution of the family, loss of personal dignity and economic exploi tation endured by the working class. But Zille also showed their entertainments, their diversions, their excesses. In so doing, Zille laid bare the grim and the droll realities of urban life, perceived with a steady, unflinching gaze. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . S S S . vi CHRONOLOGY . xi Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 5 . 1 II. AN OVERVIEW: BERLIN, ART AND ZILLE . 8 III. "ART FROM THE GUTTER:" ZILLE'S THEMATIC CHOICES .