Kennedy, Adenauer and the Making of the Berlin Wall 1958-1961 a Dissertation Submitted to the Department of History and the Comm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violence and the Word

Essays Violence and the Word Robert M. Coverf I. INTRODUCTION: THE VIOLENCE OF LEGAL ACTS Legal interpretation' takes place in a field of pain and death. This is true in several senses. Legal interpretive acts signal and occasion the im- position of violence upon others: A judge articulates her understanding of a text, and as a result, somebody loses his freedom, his property, his chil- dren, even his life. Interpretations in law also constitute justifications for violence which has already occurred or which is about to occur. When interpreters have finished their work, they frequently leave behind victims whose lives have been torn apart by these organized, social practices of violence. Neither legal interpretation nor the violence it occasions may be properly understood apart from one another. This much is obvious, though the growing literature that argues for the centrality of interpretive practices in law blithely ignores it.2 t Chancellor Kent Professor of Law and Legal History, Yale University. There are always legends of those who came first, who called things by their right names and thus founded the culture of meaning into which we latecomers are born. Charles Black has been such a legend, striding across the landscape of law naming things, speaking "with authority." And we who come after him are eternally grateful. I wish to thank Harlon Dalton, Susan Koniak and Harry Wellington for having read and com- mented upon drafts of this essay. Some of the ideas in this essay were developed earlier, in the Brown Lecture which I delivered at the Georgia School of Law Conference on Interpretation in March, 1986. -

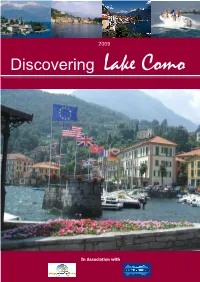

Discovering Lake Como

2009 Discovering Lake Como In Association with Welcome to Lake Como Homes About our Company Lake Como Homes in and can provide helpful Lake Como FREE conjunction with our partners assistance whatever your Advantage Card with every Happy Holiday Homes are now needs. rental booking! established as the leading property management and The Happy Holiday Homes letting company covering Lake team is here to assist you in Como. having a memorable holiday Advantage Card 2009 experience in one of the most Lake Como We are proud to offer a fully beautiful Lakes in the world. comprehensive service to our www.happyholidayhomes.net +39 0344 31723 customers and are equally Try our Happy Service which delighted in being able to offer specialises in sourcing our clients a wide and diverse exceptional good value deals on selection of holiday homes local events and activities and from contemporary studio passing the savings directly apartments to Luxurious onto you. This represents a discount to modern and period style Villas. many of the attractions and We thank you in selecting Lake Eateries about the lake. Happy Holiday Homes, based Como Homes and Happy in Menaggio have an Holiday Homes for your holiday enthusiastic multi-lingual team in the Italian Lakes. providing a personal service Happy Holiday Homes©, Via IV Novembre 39, 22017, Menaggio, Lake Como – www.happyholidayhomes.net - Tel: +39 034431723 Beauty in every sense of the word The Lake is shaped rather like an inverted 'Y', with two 'legs' starting at Como in the South- West and Lecco in the South-East, which join together half way up and the lake continues up to Colico in the North. -

San Martino 2

Passeggiate Tremezzo 2011_Layout 1 27/04/11 10.06 Pagina 7 SAN MARTINO 2 San Martino is a small church located at an altitude of 475 m on the slopes of Sasso S.Martino above Griante An easy path leads to the church from where you have a lovely view of the central lake area. Starting point: Tremezzo (or the parking lot at Rogaro – see walk 3 how to reach it) Itinerary: Tremezzo - Rogaro - San Martino - Griante - Cadenabbia - Tremezzo Total duration of the walk: 2.30 hours ascent: 275m - some signs indicating S.Martino difficulty: good walking shoes required Route: From the boat dock of Tremezzo next to the tourist information office cross the main road and in a slight descent to the right. It ends on to the trail pick up the cobble stone alley called, via Selve di that leads up from Griante to San Martino that you Rogaro, that leads to the hamlet Rogaro . At the end reach shortly. of the long steep flight of steps you end up on a paved The S. Martino church was built in the XVI century road near the tower of Rogaro. This watch tower to house the wooden statue of the 14th century repre - belonged to the important family Visconti and it was senting the Madonna with Child . The legend tells part of the defensive system of the Comacina Island. that the statue was found in the 16th century by a Before turning left we recommend a small deviation shepherd girl in a cave in the mountains where it was to the right in order to admire “ la Catapecchia ”, a put a century before by an inhabitant of Menaggio villa built at the end of the 18 th century by the bishop when the town was destroyed by the Grigioni. -

Bibliography

Bibliography I. Primary Sources A. Manuscript Collections and Government Archives Foreign Affairs Oral History Program (FAOHP), Georgetown University Washington, D.C. (copies also deposited at George C. Marshall Library) Everett Bellows (February 1989) David S. Brown (March 1989) Vincent V. Checchi (July 1990) Lincoln Gordon (January 1988) John J. Grady (August 1989) William Parks (November 1988) Melbourne Spector (December 1988) Joseph Toner (October 1989) Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. W. Averell Harriman Papers George C. Marshall Library, Lexington, Virginia Dowsley Clark Collection European Recovery Plan Commemoratives Collection William C. Foster Papers George C. Marshall Papers Marshall Plan Photograph Collection Forrest Pogue Interviews (Paul Hoffman and John McCloy) Harry B. Price Interviews (conducted 1952–54) ECA and OEEC Leland Barrows Richard M. Bissell Samuel Board Harlan Cleveland H. Van B. Cleveland John O. Coppock Glenn Craig D. A. Fitzgerald William C. Foster Theodore Geiger Lincoln Gordon W. Averell Harriman Carroll Hinman Paul Hoffman E. N. Holmgren John Lindeman Shaw Livermore Robert Marjolin Orbun V. Powell MacDonald Salter Melbourne Spector Harold Stein Donald C. Stone Allan Swim Samuel Van Hyning Greece (Americans) Michael H. B. Adler Leland Barrows Dowsley Clark John O. Coppock Helene Granby Joseph F. Heath Robert Hirschberg Paul A. Jenkins Brice M. Mace Lawrence B. Myers Walter E. Packard Paul R. Porter 163 Bibliography Greece (Americans—continued) Alan D. Strachan Edward A. Tenenbaum John O. Walker Greece (Greeks) Costa Hadjiagyras Constantin D. Tsatsos Italy (Americans) Vincent M. Barnett William E. Corfitzen Henry J. Costanzo Bartlett Harvey Thomas A. Lane Dominic J. Marcello Walter C. McAdoo Guido Nadzo Chauncey Parker Donald Simmons James Toughill Italy (Italians) Giovanni Malagodi Donato Menichella Ernesto Rossi Turkey (Americans) Clifton H. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 1961

*r r" : • »■! S Journal Service Foreign POWERFUL WRITTEN SWARTZDid you write for the new catalogue? 600 South Pulaski Street, Baltimore 23. INCREDIBLE is understating the power of the burgeoning NATURAL SHOULDER suit line (for fall 1961-62 whose delivery begins very soon.) Premium machine (NOT hand-needled) it has already induced insomnia among the $60 to $65 competitors—(with vest $47.40) coat & pant Today, the success or failure of statesmen, businessmen and industrialists is often determined by their A man knowledge of the world’s fast-changing scene. To such men, direct news and information of events transpiring anywhere in the world is of vital necessity. It ivho must know influences their course of action, conditions their judgement, solidifies their decisions. And to the most successful of what’s going on these men, the new all-transistor Zenith Trans-Oceanic portable radio has proved itself an invaluable aide. in the world For the famous Zenith Trans-Oceanic is powered to tune in the world on 9 wave bands . including long wave ... counts on the new and Standard Broadcast, with two continuous tuning bands from 2 to 9 MC, plus bandspread on the 31,25,19,16 and 13 meter international short wave bands. And it works on low-cost flashlight batteries available anywhere. No need for AC/DC power outlets or “B” batteries! ZENITH You can obtain the Zenith Trans-Oceanic anywhere in the free world, but write — if necessary — for the name of your nearest dealer. And act now if you’re a man all-transistor who must know what’s going on in the world — whether you’re at work, at home, at play or traveling! TRANS-OCEAN: world’s most magnificent radio! The Zenith Trans-Oceanic is the only radio of its kind in the world! Also available, without the long wave band, as Model Royal 1000. -

Escape to Freedom: a Story of One Teenager’S Attempt to Get Across the Berlin Wall

Escape to Freedom: A story of one teenager’s attempt to get across the Berlin Wall By Kristin Lewis From the April 2019 SCOPE Issue Every muscle in Hartmut Richter’s body ached. He’d been in the cold water for four agonizing hours. His body temperature had plummeted dangerously low. Now, to his horror, he found himself trapped in the water by a wall of razor-sharp barbed wire. Precious seconds ticked by. The area was crawling with guards carrying machine guns. Some had snarling dogs at their sides. If they caught Hartmut, he could be thrown in prison—or worse. These men were trained to shoot on sight. Hartmut grabbed the wire with his bare hands. He began pulling it apart, hoping he could make a hole large enough to squeeze through. Hartmut Richter was not a criminal escaping from jail. He was not a bank robber on the run. He was simply an 18-year-old kid who wanted nothing more than to be free—to listen to the music he wanted to listen to, to say what he wanted to say and think what he wanted to think. And right now, Hartmut was risking everything to escape from his country and start a new life. A Bleak Time Hartmut was born in Germany in 1948. He lived near the capital city of Berlin with his parents and younger sister. This was a bleak time for his country. Only three years earlier, Germany had been defeated in World War II. During the war, Germany had invaded nearly every other country in Europe. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 9-12-1962 Kabul Times (September 12, 1962, vol. 1, no. 155) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (September 12, 1962, vol. 1, no. 155)" (1962). Kabul Times. 153. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/153 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - , - > • -~ ....... , 1 •• " , '. -:- ~.-'-- '-':'....,....~ - . ~ ... -' .., ...... ~4 ~ ,:",.:~ ":S~'" . .' . :\. - 4 •• :-_ _- - '. .- :.. -r: 'S._ ""__'" _ _ - _-_ k ,- ~ • ¢ • - • '. -~•• . j -.-- ~:... :.,--.- .-' .. '. .... ' .. .- . - •- j"-- - -" . ~ " .' ,. l .I' , - .. .' ., .' .' .I .:1tABUL mas··_, '- ·"'M4iJmum· +28°Co , Minimum +l%°C. (;on1~oli~e~lth Pr~miers. KennrAly'~:r .Sun.sets ~ at s:ZO 'p.m. Piess .'.Review· With . SuD rises- toJDorrow- at 5-36 a.m. ~ " ; . ~ ~~- "~" ~-.:r'.'_:::-~ ~ -::~. ~ .~-:;~'.' . ~(CoDtd. trom PaCe·!) ., :·.Briefea~·On···r~·Brussels.·~Tcdks· ·:(~Af~~'fd~~i'Ke~~ y;:~ ~ .. o .' '. • "'./ - ::",-." :'.""'" :._ •••• i''''J o:--t:- '.:", .•. ",- • CIw'; 4..::. _. 'Jt·. ., -' .'_ ,- , ~'--:.-cians· ~t t~rday: usse ~hthe. ~iepu~~: .... .-. ': .... :.... ~.:~ '...':; .:·::':·.·.-.·:::::~·.~·r ~. '.~:--': ~ .:":.' ". -~... ~.-.:-.::.:;. ,~~ .'~~'A'r+! ± _~n:;~l·:;:~~"'!:: ~:: ~::~~ .~ should'reveal the. f.acts: '. - '0',7 , U.K' "1 < Et< ". " '," t' 'C M' .' m:: ·d ' .... The -same issue of the . paper· . n· '. "5 ntry' no' SIOns m ~rlin Wl .~. • L.':'~'!"·""'·liiIiiil·IIit!oo"';"~""~~ VOL- 1,. NO.. 155 WEDNESD~~:, .S~.~~ (SOMBpLElr~21;' ~: ~ :" { carries ~ report'abOut the Woollen:.· .' '" .....•. ..." :'. .' ., •...• ".can pred~cessor. MJ::. E~nhower. -

Tageszeitung (Taz) Article on the Opening of the Berlin Wall

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9, 1989) Two journalists from Die Tageszeitung (taz), a left-of-center West Berlin newspaper, describe the excitement generated by the sudden opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. The event was the result of internal pressure applied by East German citizens, and it evoked spontaneous celebration from a people who could once again freely cross the border and rekindle relationships with friends and relatives on the other side. (Please note: the dancing bear mentioned below is a figurative reference to West Berlin's official mascot. Beginning in 1954, the flag of West Berlin featured a red bear set against a white background. In 1990, the bear became the mascot of a unified Berlin. The former West Berlin flag now represents the city as a whole.) "We Want In!" The Bear Is Dancing on the Border Around midnight, RIAS – the American radio station broadcasting to the East – still has no traffic interruptions to report. Yet total chaos already reigns at the border checkpoint on Invalidenstrasse. People parked their cars at all conceivable angles, jumped out, and ran to the border. The transmission tower of the radio station "Free Berlin" is already engulfed by a throng of people (from the West) – waiting for the masses (from the East) to break through. After three seconds, even the most hardened taz editor finds himself applauding the first Trabi he sees. Everyone gets caught up in the frenzy, whether she wants to or not. Even the soberest members of the crowd are applauding, shrieking, gasping, giggling. -

YUGOSLAV-SOVIET RELATIONS, 1953- 1957: Normalization, Comradeship, Confrontation

YUGOSLAV-SOVIET RELATIONS, 1953- 1957: Normalization, Comradeship, Confrontation Svetozar Rajak Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London School of Economics and Political Science University of London February 2004 UMI Number: U615474 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615474 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ” OF POUTICAL «, AN0 pi Th ^ s^ s £ £2^>3 ^7&2io 2 ABSTRACT The thesis chronologically presents the slow improvement of relations between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, starting with Stalin’s death on 5 March 1953, through their full normalization in 1955 and 1956, to the renewed ideological confrontation at the end of 1956. The normalization of Yugoslav-Soviet relations brought to an end a conflict between Yugoslavia and the Eastern Bloc, in existence since 1948, which threatened the status quo in Europe. The thesis represents the first effort at comprehensively presenting the reconciliation between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, between 1953 and 1957. It will also explain the motives that guided the leaderships of the two countries, in particular the two main protagonists, Josip Broz Tito and Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, throughout this process. -

ISUM #3, Per10d Ending 142400 Dec 61

, 6-2.. • S'=I'R..."'~ ET. HEAIlQUARTElIS BERLIN BRIGADE Off ice of the AC of 8, G2 APO 742 US FOR::ES + 1 . (8 \ ~!l..'ClE1' FORCES: a. Hf'llccpter f light over Installation 4154 and AUf,J'1..lst Bebel PIa t."':t.:1 E.l.f"t Ber::'ln on 13 December revealed the following: (1) 29 T-S4 tanks , 1 BTR ~ 1 bus and 3 wheeled vehicles are lonat;u 1n August Ecbel Platz. (2) Tho tanks that were parked 1n Installation 4154 are n':) 10n3C'r jX.rkC'd oJ!" th::! hardstand inside the in::>tall at:'..on . 02 C:nlr.l.Cnt: It 1s possible thf'.t 10 to 12 tunI.s w'uld b,- p~.~'·:(r0. inside ::::h3ds 1n Insullatlon 415 1~ . Br;1 l.icved, ho~·e"E.r, thE'.t fO.ll tt.rks h'we dep.-,rtcd this installation. Tank unit in Bebel Platz 1s b_'1.i8ved to be Jchc Tt..nk Battalion, 83d Motorized Riflo il0giment fr.i:n Installation 4161 1n Karlshorst. Un! t to have departed IlStnllatl~n 4154 believe d to be a tank battalion of 68th Tnnk Regiment f rom InstallE:.tion 4102 (Berl~n Blesdorf). b . Headquarters, GSfo'G imposed new permanent 1'cstrictions on Wcs.tern Mili t:-", ry Missions effective 12000:1. December 1961. The new restrictcd c.r .m,s are located in Schwerin-~udwiglust, W:Ltt.3nburg and Ko·~igsb ru ,ck areas. The permanent r es tric ted areas of Guestrow; Letzlingcr lI~ide . Altengrabow. Jena-Weissenfe1s, Ohrdrv.f and Juetcl'bog were exten,Ld. -

Irina Liebmann Und Der Doppelgänger

https://doi.org/10.25620/ci-03_13 CATHERINE SMALE »Wir sind wie Spiegel« Irina Liebmann und der Doppelgänger ZITIERVORGABE: Catherine Smale, »»Wir sind wie Spiegel«: Irina Liebmann und der Doppelgänger«, in Phantasmata: Techniken des Unheimlichen, hg. v. Martin Doll, Rupert Gaderer, Fabio Camilletti und Jan Niklas Howe, Cultural Inquiry, 3 (Wien: Turia + Kant, 2011), S. 203–17 <https: //doi.org/10.25620/ci-03_13> ANGABE ZU DEN RECHTEN: Phantasmata: Techniken des Unheimlichen, hg. © by the author(s) v. Martin Doll, Rupert Gaderer, Fabio Camil- This version is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- letti und Jan Niklas Howe, Cultural Inquiry, 3 ShareAlike 4.0 International License. (Wien: Turia + Kant, 2011), S. 203–17 SCHLAGWÖRTER: Freud, Sigmund – Das Unheimliche; Psychoanalyse; Doppelgänger (Motiv); Liebmann, Irina – Die freien Frauen; Liebmann, Irina – In Berlin; Berliner Mauer (Motiv); Deutschland (Motiv) / Teilung (Motiv); Spiegelung (Motiv); Mise en abyme The ICI Berlin Repository is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the dissemination of scientific research documents related to the ICI Berlin, whether they are originally published by ICI Berlin or elsewhere. Unless noted otherwise, the documents are made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.o International License, which means that you are free to share and adapt the material, provided you give appropriate credit, indicate any changes, and distribute under the same license. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ for further details. In particular, you should indicate all the information contained in the cite-as section above. ¨8*34*/%8*&41*&(&-§ *SJOB-JFCNBOOVOEEFS%PQQFMHjOHFS1 $BUIFSJOF4NBMF If the story of the ›Doppelgänger‹ has to break off here for the purposes of this book, it is certainly not finished yet.