Parsons 31..67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Britain

Roman Britain Hadrian s Wall - History Vallum Hadriani - Historia “ Having completely transformed the soldiers, in royal fashion, he made for Britain, where he set right many things and - the rst to do so - drew a wall along a length of eighty miles to separate barbarians and Romans. (The Augustan History, Hadrian 11.1)” Although we have much epigraphic evidence from the Wall itself, the sole classical literary reference for Hadrian having built the Wall is the passage above, wrien by Aelius Spartianus towards the end of the 3rd century AD. The original concept of a continuous barrier across the Tyne-Solway isthmus, was devised by emperor Hadrian during his visit to Britain in 122AD. His visit had been prompted by the threat of renewed unrest with the Brigantes tribe of northern Britain, and the need was seen to separate this war-like race from the lowland tribes of Scotland, with whom they had allied against Rome during recent troubles. Components of The Wall Hadrian s Wall was a composite military barrier which, in its nal form, comprised six separate elements; 1. A stone wall fronted by a V-shaped ditch. 2. A number of purpose-built stone garrison forti cations; Forts, Milecastles and Turrets. 3. A large earthwork and ditch, built parallel with and to the south of the Wall, known as the Vallum. 4. A metalled road linking the garrison forts, the Roman Military Way . 5. A number of outpost forts built to the north of the Wall and linked to it by road. 6. A series of forts and lookout towers along the Cumbrian coast, the Western Sea Defences . -

Galway City Walls Conservation, Management and Interpretation Plan

GALWAY CITY WALLS CONSERVATION, MANAGEMENT & INTERPRETATION PLAN MARCH 2013 Frontispiece- Woman at Doorway (Hall & Hall) Howley Hayes Architects & CRDS Ltd. were commissioned by Galway City Coun- cil and the Heritage Council to prepare a Conservation, Management & Interpre- tation Plan for the historic town defences. The surveys on which this plan are based were undertaken in Autumn 2012. We would like to thank all those who provided their time and guidance in the preparation of the plan with specialist advice from; Dr. Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Dr. Kieran O’Conor, Dr. Jacinta Prunty & Mr. Paul Walsh. Cover Illustration- Phillips Map of Galway 1685. CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE 6 3.0 PHYSICAL EVIDENCE 17 4.0 ASSESSMENT & STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 28 5.0 DEFINING ISSUES & VULNERABILITY 31 6.0 CONSERVATION PRINCIPLES 35 7.0 INTERPRETATION & MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES 37 8.0 CONSERVATION STRATEGIES 41 APPENDICES Statutory Protection 55 Bibliography 59 Cartographic Sources 60 Fortification Timeline 61 Endnotes 65 1.0 INTRODUCTION to the east, which today retains only a small population despite the ambitions of the Anglo- Norman founders. In 1484 the city was given its charter, and was largely rebuilt at that time to leave a unique legacy of stone buildings The Place and carvings from the late-medieval period. Galway City is situated on the north-eastern The medieval street pattern has largely been shore of a sheltered bay on the west coast of preserved, although the removal of the walls Ireland. It is located at the mouth of the River during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Corrib, which separates the east and western together with extra-mural developments as the sides of the county. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

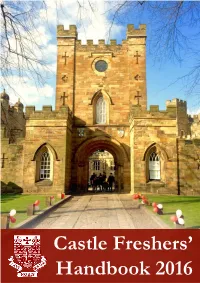

Castle Freshers' Handbook 2016

Castle Freshers’ Handbook 2016 2 Contents Welcome - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Your JCR Executive Committee - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 Your International Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Your Male Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -13 Your Female Freshers’ Representatives- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 15 Your Welfare Team - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Your Non-Executive Officers - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 21 JCR Meetings - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 24 College Site Plan - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 25 Accommodation in College - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -27 What to bring to Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -28 College Dictionary - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 29 The Key to the Lowe Library - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Social life in Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Our College’s Sports - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Our College’s Societies - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -46 Durham Students’ Union and Team Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 52 General -

Martello Towers Research Project

Martello Towers Research Project March 2008 Jason Bolton MA MIAI IHBC www.boltonconsultancy.com Conservation Consultant [email protected] Executive Summary “Billy Pitt had them built, Buck Mulligan said, when the French were on the sea”, Ulysses, James Joyce. The „Martello Towers Research Project‟ was commissioned by Fingal County Council and Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, with the support of The Heritage Council, in order to collate all known documentation relating to the Martello Towers of the Dublin area, including those in Bray, Co. Wicklow. The project was also supported by Dublin City Council and Wicklow County Council. Martello Towers are one of the most well-known fortifications in the world, with examples found throughout Ireland, the United Kingdom and along the trade routes to Africa, India and the Americas. The towers are typically squat, cylindrical, two-storey masonry towers positioned to defend a strategic section of coastline from an invading force, with a landward entrance at first-floor level defended by a machicolation, and mounting one or more cannons to the rooftop gun platform. The Dublin series of towers, built 1804-1805, is the only group constructed to defend a capital city, and is the most complete group of towers still existing in the world. The report begins with contemporary accounts of the construction and significance of the original tower at Mortella Point in Corsica from 1563-5, to the famous attack on that tower in 1794, where a single engagement involving key officers in the British military became the catalyst for a global military architectural phenomenon. However, the design of the Dublin towers is not actually based on the Mortella Point tower. -

Strukturdaten Des IHK-Gremiums Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Stand Februar 2019

Strukturdaten des IHK-Gremiums Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Strukturdaten des IHK-Gremiums Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Stand Februar 2019 Industrie- und Handelskammer Nürnberg für Mittelfranken Ulmenstraße 52 | 90443 Nürnberg Tel: 0911 1335-375 | Fax: 0911 1335-150375 | [email protected] | www.ihk-nuernberg.de Strukturdaten des IHK-Gremiums Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Das IHK-Gremium Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Vorsitz Paul Habbel, Lebendige Organisation GmbH Im Winkel 40 91757 Treuchtlingen [email protected] Telefon: 09141 9975-101 Stellvertretende Vorsitzende 1. Stellvertretender Vorsitz Hans-Georg Degenhart, Degenhart Eisenhandel GmbH & Co. KG Leiter der IHK Geschäftsstelle Karin Bucher, IHK Nürnberg für Mittelfranken, Bahnhofsplatz 8 91522 Ansbach [email protected] Telefon: 0981 209570-01 Telefax: 0981 209570-29 Industrie- und Handelskammer Nürnberg für Mittelfranken Ulmenstraße 52 | 90443 Nürnberg Tel: 0911 1335-375 | Fax: 0911 1335-150375 | [email protected] | www.ihk-nuernberg.de Strukturdaten des IHK-Gremiums Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Das IHK-Gremium Weißenburg Gunzenhausen Mitglieder Wahlgruppe Dienstleistung Markus Etschel, Etschel netkey GmbH, Weißenburg i. Bay. Klaus Horrolt, Parkhotel Altmühltal GmbH & Co. KG, Gunzenhausen Stefan Hueber, Hueber GmbH & Co. KG, Pleinfeld Harald Höglmeier, HB-B Höglmeier Beratungs- und Beteiligungs GmbH, Ellingen Gerhard Müller, Hotel Adlerbräu GmbH & Co. KG, Gunzenhausen Matthias Schork, Spedition Wüst GmbH & Co. KG, Weißenburg Wahlgruppe Handel Hans-Georg Degenhart, Degenhart Eisenhandel GmbH & Co. KG, Gunzenhausen Erika Gruber, Zweirad Gruber GmbH, Gunzenhausen Reiner Hackenberg, STABILO International GmbH, Heroldsberg Christina Kühleis, Foto Gebhardt & Lahm Inh. Christina Kühleis e. K., Treuchtlingen Mathias Meyer, Karl Meyer Buch + Papier Inh. Mathias Meyer, Weißenburg i. Bay. Hans Riedel, Huber & Riedel GmbH, Gunzenhausen Henriette Schlund, Wohnwiese Einrichtungen Jette Schlund, Ellingen Wahlgruppe Industrie Dr.-Ing. -

Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Fought under the walls of Bergida Citation for published version: Brown, CJ, Torres-martínez, JF, Fernández-götz, M & Martínez-velasco, A 2018, 'Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 115-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Conflict Archaeology Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Brown, C. J., Torres-martínez, J. F., Fernández-götz, M., & Martínez-velasco, A. (2018). Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 12(2), which has been published in final form at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

VGN – Lokal Spezial Stadtverkehr Gunzenhausen

m ur rt 2 • Die umliegenden Ortsteile wer- e Ihre Tickets für Fahrten innerhalb der b Über 15.800 km Verbundgebiet stehen Ihnen weit r Stadtverkehr Gunzenhausen ä F den von insgesamt 9 Regio nal- Stadt Gunzenhausen offen. Mit nur einer VGN-Fahrkarte können Sie rund bus linien an den Bahnhof und 780 Bus- und Bahnlinien nutzen – ganz bequem und € Preisstufe F 637 Igelsbach die Kernstadt angebunden. 744 Merkendorf z weiterhin günstig. Denn der VGN hält das passende t Mitteleschenbach R 8 Marktbreit Spalt a 621 l Einfache Fahrt Erwachsene 1,30 p • Außerdem sind die Ortsteile von t Angebot bereit: für Gelegenheits-Fahrer genauso wie für rk Kind 0,60 Gunzenhausen und mehrere Umland- Ma Dauernutzer, für Beruf, Shopping oder Freizeit. gemeinden abends mit einem Anrufsammeltaxi (AST) 4er-Ticket Erwachsene 5,00 Kind 2,50 vom bzw. zum Bahnhof Gunzenhausen angebunden. TagesTicket Solo 1 Person, Tag o. Wochenende 2,80 Schlungenhof Gute Fahrt wünschen Ihnen Laubenzedlerstr. TagesTicket Plus Tag oder Wochenende 4,70 Mitte die Stadt Gunzenhausen und der VGN! Pleinfeld MobiCard ** 7-Tage-MobiCard 9,70 744 9-Uhr-MobiCard, 31 Tage 26,70 Betriebshof Fichtenweg R62 31-Tage-MobiCard 33,20 Ebert Breslauer Str. Ansbacher Str. Carlo-Loos-Str. Weinstr. Wiesen- Bahnhof Gunzenhausen 77 Parkplätze Nürnberger Str. Spitalfeldstr. str. Im Eisenreich Solo 31 * 1 Person, 31 Tage 29,80 648 649 Waldstr. R62 621 637 639 Schlesierstr. 188 Fahrradstellplätze Lerchenstr. 640 641 648 649 Bahnhof Zufuhrstr. Zeppelinstr. Stuttgarter Str. Stein- Schulstr. Bechhofen 829 kreuzstr. Abo 3 * 1 Person, 3 Monate mtl. 28,20 744 801.1 801.2 Ärztehaus Blütenstr. -

Rebuilding the Soul: Churches and Religion in Bavaria, 1945-1960

REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 _________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________ by JOEL DAVIS Dr. Jonathan Sperber, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2007 © Copyright by Joel Davis 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled REBUILDING THE SOUL: CHURCHES AND RELIGION IN BAVARIA, 1945-1960 presented by Joel Davis, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________ Prof. Jonathan Sperber __________________________________ Prof. John Frymire __________________________________ Prof. Richard Bienvenu __________________________________ Prof. John Wigger __________________________________ Prof. Roger Cook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a number of individuals and institutions whose help, guidance, support, and friendship made the research and writing of this dissertation possible. Two grants from the German Academic Exchange Service allowed me to spend considerable time in Germany. The first enabled me to attend a summer seminar at the Universität Regensburg. This experience greatly improved my German language skills and kindled my deep love of Bavaria. The second allowed me to spend a year in various archives throughout Bavaria collecting the raw material that serves as the basis for this dissertation. For this support, I am eternally grateful. The generosity of the German Academic Exchange Service is matched only by that of the German Historical Institute. The GHI funded two short-term trips to Germany that proved critically important. -

Fahrradvermietungen

Fahrradvermietungen Über die Radwege im Bereich "Fränkisches Seenland" informiert der Prospekt "Radwandern", Maßstab 1:100000, mit Kurzbeschreibungen. Auskunft, Prospekte und Information: Tourismusverband "Fränkisches Seenland" Hafnermarkt 13 91710 Gunzenhausen Telefon 09831/ 5001-20, Telefax 09831/5001-40, E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.fraenkischeseen.de Rikschas sind für Urlauber mit Handicap geeignet; für Sehbehinderte und Blinde mit Begleitperson stehen Rikschas oder Tandems zur Verfügung Gunzenhausen: Surfzentrum Gunzenhausen-Schlungenhof, 91710 Gunzenhausen, Telefon 09831/1233 oder 1240, E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: www.surfcenter-altmuehlsee.de. 15 Räder, 2 Rikschas. Gebühr: 1 Stunde 2,50 €, 3 Stunden 5,- €, Tag 7,50 €. Seezentrum Gunzenhausen-Schlungenhof , Telefon 0171/2658315, 09831/2177. Gebühr: nach Vereinbarung. 70 Fahrräder (auch Kinderfahrräder), 10 Rikschas (überdacht), Tandems, behindertengerechte Fahrräder. Radsport-Gruber, Weißenburger Straße 49, 91710 Gunzenhausen, Telefon 09831/2177. Internet: www.radsport-gruber.de E-Mail: [email protected] Gebühr: 6,- € je Tag (Vor- und Nachsaison 5,- €), 2 Stunden 3,- € (am See). 130 Fahrräder, 8 Rikschas, 2 Tandems, Mountainbikes. 10 Kinderräder ab 16 Zoll, Kindersitze und Kinderanhänger. SAN-aktiv-TOURS, Spitalstraße 26, Nähe Parkplatz Zentrum-Nord. Mobiler Fahrradverleih, ca. 450 Fahrräder aller Größen im Verleih sowie Rikschas, Tandems, Kinderanhänger und weiteres Zubehör. Damen-, Herren- und Kinderräder 8,- €/Tag, bis 2 Stunden 3,50 €, bis 4 Stunden 6,- €. Abendtarif (18 bis 9 Uhr) 5,50 €, Fitnessbikes 13,- €/Tag, bis 2 Stunden 6,50 €. Sonderpreise in Gunzenhausen, Spitalstraße 26 (ab 4,50 €/Tag und Rad). Information, Reservierung und Buchung bei: SAN-aktiv-TOURS, Bühringerstraße 11, 91710 Gunzenhausen, Telefon 09831/4936, Telefax 09831/80594. Internet: www.san-aktiv-tours.de Seezentrum Gunzenhausen - Wald: SAN-aktiv-TOURS, Bühringerstraße 11, 91710 Gunzenhausen, Telefon 09831/4936, Telefax 80594. -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.