Roman Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map for Day out One Hadrian's Wall Classic

Welcome to Hadian’s Wall Country a UNESCO Arriva & Stagecoach KEY Map for Day Out One World Heritage Site. Truly immerse yourself in Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east A Runs Daily the history and heritage of the area by exploring 685 Hadrian’s Wall Classic Tickets and Passes National Trail (See overleaf) by bus and on foot. Plus, spending just one day Arriva Cuddy’s Crags Newcastle - Corbridge - Hexham www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east Alternative - Roman Traveller’s Guide without your car can help to look after this area of X85 Runs Monday - Friday Military Way (Nov-Mar) national heritage. Hotbank Crags 3 AD122 Rover Tickets The Sill Walk In this guide to estbound These tickets offer This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave Milecastle 37 Housesteads eet W unlimited travel on Parking est End een Hadrian’s Wall uns r the AD122 service. Roman Fort the confines of your car behind and truly “walk G ee T ont Str ough , Hexham Road Approx Refreshments in the footsteps of the Romans”. So, find your , Lion and Lamb journey times Crag Lough independent spirit and let the journey become part ockley don Mill, Bowes Hotel eenhead, Bypass arwick Bridge Eldon SquaLemingtonre Thr Road EndsHeddon, ThHorsler y Ovington Corbridge,Road EndHexham Angel InnHaydon Bridge,Bar W Melkridge,Haltwhistle, The Gr MarketBrampton, Place W Fr Scotby Carlisle Adult Child Concession Family Roman Site Milecastle 38 Country Both 685 and X85 of your adventure. hr Sycamore 685 only 1 Day Ticket £12.50 £6.50 £9.50 £26.00 Haydon t 16 23 27 -

HADRIAN's WALL WORLD HERITAGE SITE Management Plan

HADRIAN’S WALL WORLD HERITAGE SITE Management Plan July 1996 ENGLISH HERITAGE HADRIAN’S WALL WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Hadrian’s Wall Management Plan July 1996 HADRIAN’S WALL WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN CONTENTS Page Forward Overview 1. Introduction 1 2. The boundaries of the World Heritage Site 7 3. The need for a Management Plan 11 4. The status and objectives of the Management Plan 13 5. Date and research 19 6. Conservation and enhancement of the World Heritage Site and its Setting 21 7. Treatment of the built-up areas of the World Heritage Site 25 8. Public access, transport and tourism 29 9. Making things happen 39 Maps 1 - 20: Proposed extent of the World Heritage Site and its Setting. Annex A: References to World Heritage Sites in Planning Policy Guidance Note: 15. Annex B: Scheduled Ancient Monuments forming detached parts of the World Heritage Site. Hadrian’s Wall Management Plan July 1996 OVERVIEW Hadrian's Wall, started by the Emperor Hadrian in AD 122, is an historic and cultural phenomenon of international significance. A treasured national landmark, it is the most important monument left behind by the Romans during their occupation of Britain. It is also the best known and best preserved frontier within the whole Roman world. From the Wall, its northernmost boundary, the Roman Empire stretched 1,500 miles south to the deserts of the Sahara, and 2,500 miles east to what is present-day Iraq. The Wall stands today as a reminder of such past glories. A symbol of power, it remains an awe-inspiring testament to Roman mastery of the ancient world. -

ROMANO- BRITISH Villa A

Prehistoric (Stone Age to Iron Age) Corn-Dryer Although the Roman villa had a great impact on the banks The excavated heated room, or of the River Tees, archaeologists found that there had been caldarium (left). activity in the area for thousands of years prior to the Quarry The caldarium was the bath Roman arrival. Seven pots and a bronze punch, or chisel, tell house. Although this building us that people were living and working here at least 4000 was small, it was well built. It years ago. was probably constructed Farm during the early phases of the villa complex. Ingleby Roman For Romans, bath houses were social places where people The Romano-British villa at Quarry Farm has been preserved in could meet. Barwick an area of open space, in the heart of the new Ingleby Barwick housing development. Excavations took place in 2003-04, carried out by Archaeological Services Durham University Outbuildings (ASDU), to record the villa area. This included structures, such as the heated room (shown above right), aisled building (shown below right), and eld enclosures. Caldarium Anglo-Saxon (Heated Room) Winged With the collapse of the Roman Empire, Roman inuence Preserved Area Corridor began to slowly disappear from Britain, but activity at the Structure Villa Complex villa site continued. A substantial amount of pottery has been discovered, as have re-pits which may have been used for cooking, and two possible sunken oored buildings, indicating that people still lived and worked here. Field Enclosures Medieval – Post Medieval Aisled Building Drove Way A scatter of medieval pottery, ridge and furrow earthworks (Villa boundary) Circular Building and early eld boundaries are all that could be found relating to medieval settlement and agriculture. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location Map for the District Described in This Book

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location map for the district described in this book AA68 68 Duns A6105 Tweed Berwick R A6112 upon Tweed A697 Lauder A1 Northumberland Coast A698 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Holy SCOTLAND ColdstreamColdstream Island Farne B6525 Islands A6089 Galashiels Kelso BamburghBa MelrMelroseose MillfieldMilfield Seahouses Kirk A699 B6351 Selkirk A68 YYetholmetholm B6348 A698 Wooler B6401 R Teviot JedburghJedburgh Craster A1 A68 A698 Ingram A697 R Aln A7 Hawick Northumberland NP Alnwick A6088 Alnmouth A1068 Carter Bar Alwinton t Amble ue A68 q Rothbury o C B6357 NP National R B6341 A1068 Kielder OtterburOtterburnn A1 Elsdon Kielder KielderBorder Reservoir Park ForForestWaterest Falstone Ashington Parkand FtForest Kirkwhelpington MorpethMth Park Bellingham R Wansbeck Blyth B6320 A696 Bedlington A68 A193 A1 Newcastle International Airport Ponteland A19 B6318 ChollerforChollerfordd Pennine Way A6079 B6318 NEWCASTLE Once Housesteads B6318 Gilsland Walltown BrewedBrewed Haydon A69 UPON TYNE Birdoswald NP Vindolanda Bridge A69 Wallsend Haltwhistle Corbridge Wylam Ryton yne R TTyne Brampton Hexham A695 A695 Prudhoe Gateshead A1 AA689689 A194(M) A69 A686 Washington Allendale Derwent A692 A6076 TTownown A693 A1(M) A689 ReservoirReservoir Stanley A694 Consett ChesterChester-- le-Streetle-Street Alston B6278 Lanchester Key A68 A6 Allenheads ear District boundary ■■■■■■ Course of Hadrian’s Wall and National Trail N Durham R WWear NP National Park Centre Pennine Way National Trail B6302 North Pennines Stanhope A167 A1(M) A690 National boundaryA686 Otterburn Training Area ArAreaea of 0 8 kilometres Outstanding A689 Tow Law 0 5 miles Natural Beauty Spennymoor A688 CrookCrook M6 Penrith This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and/or database right 2007. -

Ii. Sites in Britain

II. SITES IN BRITAIN Adel, 147 Brough-by-Bainbridge, 32 Alcester, cat. #459 Brough-on-Noe (Navia), cat. #246, Aldborough, 20 n.36 317, 540 Antonine Wall, 20 n.36, 21, 71, 160, 161 Brough-under-Stainmore, 195 Auchendavy, I 61, cat. #46, 225, 283, Burgh-by-Sands (Aballava), 100 n.4, 301, 370 118, 164 n.32, cat. #215, 216, 315, 565-568 Backworth, 61 n.252, 148 Burgh Castle, 164 n.32 Bakewell, cat. #605 Balmuildy, cat. #85, 284 Cadder, cat. #371 Bar Hill, cat. #296, 369, 467 Caerhun, 42 Barkway, 36, 165, cat. #372, 473, 603 Caerleon (lsca), 20 n.36, 30, 31, 51 Bath (Aquae Sulis), 20, 50, 54 n.210, n.199, 61 n.253, 67, 68, 86, 123, 99, 142, 143, 147, 149, 150, 151, 128, 129, 164 n.34, 166 n.40, 192, 157 n.81, 161, 166-171, 188, 192, 196, cat. #24, 60, 61, 93, 113, I 14, 201, 206, 213, cat. #38, 106, 470, 297, 319, 327, 393, 417 526-533 Caernarvon (Segontium), 42 n.15 7, Benwell (Condercum), 20 n.36, 39, 78, 87-88, 96 n.175, 180, 205, 42 n.157, 61, 101, 111-112, 113, cat. #229 121, 107 n.41, 153, 166 n.40, 206, Caerwent (Venta Silurum), 143, 154, cat. #36, 102, 237, 266, 267, 318, 198 n. 72, cat. #469, 61 7 404, 536, 537, 644, 645 Canterbury, 181, 198 n.72 Bertha, cat. #5 7 Cappuck, cat. #221 Bewcastle (Fan um Cocidi), 39, 61, I 08, Carley Hill Quarry, 162 111 n.48, 112, 117, 121, 162, 206, Carlisle (Luguvalium), 43, 46, 96, 112, cat. -

Novedades Sobre Las Termas Legionarias En Britannia

© Tomás Vega Avelaira [email protected] http://www.traianvs.net/ Novedades sobre las Termas Legionarias en Britannia Tomás Vega Avelaira [email protected] a q v a e 1. Introducción radicionalmente, las investigaciones sobre las edificaciones termales han estado en estrecha relación con ambientes civiles y, en general, con aquellos conjuntos más Tespectaculares, como por ejemplo las termas de Ca- racalla o las de Diocleciano en Roma. Como conse- cuencia de ello, en el imaginario popular se han im- plantado unas estampas excesivamente evocadoras de emperadores seguidos por interminables séquitos disfrutando de los frugales placeres de la vida. En épocas pasadas, pintores como Lawrence Alma-Ta- dema (1836-1912), plasmaban en sus lienzos escenas un tanto oníricas que contribuían a difundir una ima- gen un tanto irreal del pasado de la Ciudad Eterna e, incluso, hoy, la vida militar de los romanos, en pa- labras de Carrié, garantiza el éxito de “anacronistas” de profesión, ingenuos cineastas de cine o maliciosos autores Figura 2. “A Favourite Custom” (1909), óleo sobre tabla, de Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Tate Gallery, Londres. de historietas (Carrié, 1991: 123). Ese tipo de edificios con mayor o peor fortuna se difundió por todo el Im- perio, desde el norte de Escocia hasta los confines del Sáhara, y desde el Océano Atlántico hasta los territo- rios bañados por el Rin, el Danubio y el Eúfrates. Pero Figura 1. Termas de Caracalla en Roma. Las técnicas y las construcciones de la Ingeniería Romana 299 © Tomás Vega Avelaira [email protected] http://www.traianvs.net/ aqvae Novedades sobre las Termas Legionarias en Britannia Figura 3. -

English/French

World Heritage 36 COM WHC-12/36.COM/8D Paris, 1 June 2012 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-sixth Session Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 24 June – 6 July 2012 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8D: Clarifications of property boundaries and areas by States Parties in response to the Retrospective Inventory SUMMARY This document refers to the results of the Retrospective Inventory of nomination files of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. To date, seventy States Parties have responded to the letters sent following the review of the individual files, in order to clarify the original intention of their nominations (or to submit appropriate cartographic documentation) for two hundred fifty-three World Heritage properties. This document presents fifty-five boundary clarifications received from twenty-five States Parties, as an answer to the Retrospective Inventory. Draft Decision: 36 COM 8D, see Point IV I. The Retrospective Inventory 1. The Retrospective Inventory, an in-depth examination of the Nomination dossiers available at the World Heritage Centre, ICOMOS and IUCN, was initiated in 2004, in parallel with the launching of the Periodic Reporting exercise in Europe, involving European properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. The same year, the Retrospective Inventory was endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its 7th extraordinary session (UNESCO, 2004; see Decision 7 EXT.COM 7.1). -

A Kink in the Cosmography?

A Kink in the Cosmography? One vital clue for deciphering Roman-era names is that the order of names in the Ravenna Cosmography is geographically logical. The unknown cosmographer appears to have taken names off maps and/or itineraries that were tolerably accurate, not up to modern cartographic standards, but good enough for Roman soldiers to plan their travels logically. An apparent exception to this logic occurs near Hadrian’s Wall, where RC’s sequence of names runs thus: ... Bereda – Lagubalium – Magnis – Gabaglanda – Vindolande – Lincoigla ... The general course is clear enough, looping up from the south onto the Stanegate road (which was built earlier than the actual Wall) and then going back south. Lagubalium must be Carlisle and Vindolande must be Chesterholm, so it seems obvious that Magnis was at Carvoran and Gabaglanda was at Castlesteads. The problem is that Carvoran lies east of Castlesteads, which would make RC backtrack and put a kink in its path across the ground. Most people will simply say “So what? Cosmo made a mistake. Or his map was wrong. Or the names were written awkwardly on his map.” But this oddity prompted us to look hard at the evidence for names on and around Hadrian’s Wall, as summarised in a table on the following page. How many of the name-to-place allocations accepted by R&S really stand up to critical examination? One discovery quickly followed (a better location for Axelodunum), but many questions remain. For a start, what was magna ‘great’ about the two places that share the name Magnis, Carvoran and Kenchester? Did that name signify something such as ‘headquarters’ or ‘supply base’ in a particular period? Could another site on the Stanegate between Carlisle and Castlesteads be the northern Magnis? The fort at Chapelburn (=Nether Denton, NY59576460) would reduce the size of the kink, but not eliminate it. -

Walking in Hadrian's Wall Country

Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country Welcome to Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country The Granary, Housesteads © Roger Clegg Contents Page An Introduction to Walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country . 3 Helping us to look after Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site . 4 Hadrian’s Wall Path National Trail . 6 Three walking itineraries incorporating the National Trail . 8 Walk Grade 1 Fort-to-Fort . .Easy . .10 2 Jesmond Dene – Lord Armstrong’s Back Garden . Easy . .12 3 Around the Town Walls . Easy . .14 4 Wylam to Prudhoe . Easy . .16 5 Corbridge and Aydon Castle . Moderate . .18 6 Chesters and Humshaugh . Easy . 20 7 A “barbarian” view of the Wall . Strenuous . 22 8 Once Brewed, Vindolanda and Housesteads . Strenuous . 24 9 Cawfields to Caw Gap. Moderate . 26 10 Haltwhistle Burn to Cawfields . Strenuous . 28 11 Gilsland Spa “Popping-stone”. Moderate . 30 12 Carlisle City . Easy . 32 13 Forts and Ports . Moderate . 34 14 Roman Maryport and the Smugglers Route . Easy . 36 15 Whitehaven to Moresby Roman Fort . Easy . 38 Section 4 Section 3 West of Carlisle to Whitehaven Gilsland to West of Carlisle 14 13 12 15 2 hadrians-wall.org Cuddy’s Crag © i2i Walltown Crags © Roger Coulam River Irthing Bridge © Graeme Peacock This set of walks and itineraries presents some of the best walking in Hadrian’s Wall Country. You can concentrate on the Wall itself or sample some of the hidden gems just waiting to be discovered – the choice is yours. Make a day of it by visiting some of the many historic sites and attractions along the walks and dwell awhile for refreshment at the cafés, pubs and restaurants that you will come across. -

Notitia Dignitatum Table and Map Chapter 40, the Dux Britanniarum, from the Notitia Dignitatum Occidentis

Notitia Dignitatum table and map Chapter 40, the dux Britanniarum, from the Notitia Dignitatum Occidentis. Uncertain locations marked with an asterisk*. Placenames have been changed to the generally-accepted Latin spellings, though variations of these spellings are found in the Notitia. 17. At the disposal of viri spectabilis the Duke of the Britains Location 18. Prefect of the 6th Legion York 19. Prefect of the cavalry Dalmatarum at Praesidium *East or North Yorkshire 20. Prefect of the cavalry Crispianorum at Danum Doncaster 21. Prefect of the cavalry catafractariorum at Morbio *Piercebridge 22. Prefect of the unit of barcariorum Tigrisiensium at Arbeia South Shields 23. Prefect of the unit of Nerviorum Dictensium at Dictum *Wearmouth 24. Prefect of the unit vigilum at Concangium Chester-le-Street 25. Prefect of the unit exploratorum at Lavatris Bowes 26. Prefect of the unit directorum at Verteris Brough-under-Stainmore 27. Prefect of the unit defensorum at Braboniacum Kirkby Thore 28. Prefect of the unit Solensium at Maglonis Old Carlisle 29. Prefect of the unit Pacensium at Magis *Piercebridge 30. Prefect of the unit Longovicanorum at Longovicium Lanchester 31. Prefect of the unit supervenientium Petueriensium at Derventione *Malton 32. Along the line of the Wall 33. Tribune of the 4th cohort Lingonum at Segedunum Wallsend 34. Tribune of the 1st cohort Cornoviorum at Pons Aelius Newcastle 35. Prefect of the 1st ala Asturum at Condercum Benwell 36. Tribune of the 1st cohort Frixagorum at Vindobala Rudchester 37. Prefect of the ala Sabiniana at Hunnum Haltonchesters 38. Prefect of the 2nd ala Asturum at Cilurnum Chesters 39. -

13 Annex to Appendix B

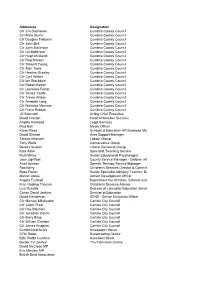

Addressee Designation Cllr Jim Buchanan Cumbria County Council Clrl Anne Burns Cumbria County Council Cllr Douglas Fairbairn Cumbria County Council Cllr John Bell Cumbria County Council Cllr John Mallinson Cumbria County Council Cllr Liz Mallinson Cumbria County Council Cllr Hugh McDevitt Cumbria County Council Cllr Reg Watson Cumbria County Council Cllr Stewart Young Cumbria County Council Cllr Alan Toole Cumbria County Council Cllr Heather Bradley Cumbria County Council Cllr Cyril Weber Cumbria County Council Cllr Ian Stockdale Cumbria County Council Cllr Robert Betton Cumbria County Council Clr Lawrence Fisher Cumbria County Council Cllr James Tootle Cumbria County Council Cllr Trevor Allison Cumbria County Council Cllr Amanda Long Cumbria County Council Cllr Nicholas Marriner Cumbria County Council Cllr Fiona Robson Cumbria County Council Jill Stannard Acting Chief Executive David Claxton Head of Member Services Angela Harwood Legal Services Paul Bell Media Officer Karen Rees Schools & Education HR Business Man David Sheard Area Support Manager Teresa Atkinson Labour Group Tony Wolfe Conservative Group Derek Houston Liberal Democrat Group Kate Astle Specialist Teaching Service Ruth Willey Senior Educational Psychologist Joan Lightfoot County Service Manager - Children wit Ana Harrison Speech Therapy Service Manager Ros Berry Children's Services Director & Commis Rose Foster Senior Specialist Advisory Teacher: De Marion Jones Autism Development Officer Angela Tunstall Department foe Children, Schools and Fran Gosling Thomas Children's