Chapter 4: INTERIOR BUILDINGS: STOREHOUSES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Britain

Roman Britain Hadrian s Wall - History Vallum Hadriani - Historia “ Having completely transformed the soldiers, in royal fashion, he made for Britain, where he set right many things and - the rst to do so - drew a wall along a length of eighty miles to separate barbarians and Romans. (The Augustan History, Hadrian 11.1)” Although we have much epigraphic evidence from the Wall itself, the sole classical literary reference for Hadrian having built the Wall is the passage above, wrien by Aelius Spartianus towards the end of the 3rd century AD. The original concept of a continuous barrier across the Tyne-Solway isthmus, was devised by emperor Hadrian during his visit to Britain in 122AD. His visit had been prompted by the threat of renewed unrest with the Brigantes tribe of northern Britain, and the need was seen to separate this war-like race from the lowland tribes of Scotland, with whom they had allied against Rome during recent troubles. Components of The Wall Hadrian s Wall was a composite military barrier which, in its nal form, comprised six separate elements; 1. A stone wall fronted by a V-shaped ditch. 2. A number of purpose-built stone garrison forti cations; Forts, Milecastles and Turrets. 3. A large earthwork and ditch, built parallel with and to the south of the Wall, known as the Vallum. 4. A metalled road linking the garrison forts, the Roman Military Way . 5. A number of outpost forts built to the north of the Wall and linked to it by road. 6. A series of forts and lookout towers along the Cumbrian coast, the Western Sea Defences . -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Fought under the walls of Bergida Citation for published version: Brown, CJ, Torres-martínez, JF, Fernández-götz, M & Martínez-velasco, A 2018, 'Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) ', Journal of Conflict Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 115-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of Conflict Archaeology Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Brown, C. J., Torres-martínez, J. F., Fernández-götz, M., & Martínez-velasco, A. (2018). Fought under the walls of Bergida: KOCOA analysis of the Roman attack on the Cantabrian oppidum of Monte Bernorio (Spain) Journal of Conflict Archaeology, 12(2), which has been published in final form at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1440993 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Report on the Society's Excavation of Rough Castle on the Antonine Vallum, by Mungo Buchanan, C.M.S.A. Scot. ; Introductory Hist

2 44 PROCEEDING E SOCIETY , 19058 TH Y F . O SMA , XI. E REPORSOCIETY'TH N O T S EXCAVATIO F ROUGO N H CASTLN O E ANTONINE TH E VALLUM MUNGY B , O BUCHANAN, C.M.S.A. SCOT; . INTRODUCTORY HISTOK DAVIE D Y YB D CHRISTISON ; DESCKIPTIO E TH F XO REUCS BY DB JOSEPH ANDERSON. (PLATES I., II.) I. HISTORY. As the funds of the Society had been considerably encroached upon in defraying the expenses of excavating Roman sites for a period of eight years, the Council instituted in 1902 a subscription among the Fellows e purposd otherth an r f continuinfo seo g that lin f investigationeo d an , ample funds were thus obtained for the excavation of Rough Castle, leavin gconsiderabla e balanc r favourou n ei . Leave having been freely grante r ForbeM y f Callandedb o s e th d ran Ver . RussellC y . J Rev r , D . proprietor e groundth f o worse th , k began earl continueds Marchyn i wa d without an , no , t some interruption frod mba weather, till October 1903. Several members of the Council kept up a general superintendence, Mr Thomas Ross's great experience being again available in directing the work. Mr Mungo Buchanan once more gave his valuable services in taking the plans, devoting every moment he could spare from his own business to a careful study of the complex structures that were revealed; and Mr Alex. Mackie, who had served us already so wel s Clera l f Worko k n foui s r excavation f Romao s n- re sites s wa , appointed on this occasion. -

Le Gisement Protohistorique De Gorge-De-Loup (Vaise - Rhône) : Campagne 1986 Catherine Bellon, Joëlle Burnouf, Jean-Michel Martin, Agnès Vérot-Bourrély

Le gisement protohistorique de Gorge-de-Loup (Vaise - Rhône) : campagne 1986 Catherine Bellon, Joëlle Burnouf, Jean-Michel Martin, Agnès Vérot-Bourrély To cite this version: Catherine Bellon, Joëlle Burnouf, Jean-Michel Martin, Agnès Vérot-Bourrély. Le gisement protohis- torique de Gorge-de-Loup (Vaise - Rhône) : campagne 1986. Bulletin de l’Association française pour l’étude de l’âge du fer, AFEAF, 1987, 5, pp.16-17. hal-02923069 HAL Id: hal-02923069 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02923069 Submitted on 26 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License 2 LES SANCTUAIRES DU ORONZE rINAL lllb D'ACY-ROMANCE (Ardennes) Fouillé depuis quatre ans, le complexe pro tohistor ique d'Acy-Romance nous a révélé, cette année encore, quelques surprises. L'an dernier 3 inhumations du Bronze Final lia -Ilb, au mobilier archéologique peu commun, étajent découvertes (LAMBOT B. - TALON M. 1987). La campagne 1986 nous a permis d'é tudier 3 sanctuaires du Bronze Final lllb. 1 - SITUATION ET ENVIRONNEMENT ARCHEOLOGIQUE Le finage de la co mmune cl'Acy-Ro mance est particulièrement riche en structures proto historiques, pratiquement adjacentes, qui méritent le terme de "complexe protohistorique" (fig. -

Rome's Northern European Boundaries by Peter S. Wells

the limes hadrian’sand wall Rome’s Northern European Boundaries by peter s. wells Hadrian’s Wall at Housesteads, looking east. Here the wall forms the northern edge of the Roman fort (the grass to the right is within the fort’s interior). In the background the wall extends northeastward, away from the fort. s l l e W . S r e t e P 18 volume 47, number 1 expedition very wall demands attention and raises questions. Who built it and why? The Limes in southern Germany and Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain are the most distinctive physical remains of the northern expansion and defense of the Roman Empire. Particularly striking are the size of these monuments today and their uninterrupted courses Ethrough the countryside. The Limes, the largest archaeological monument in Europe, extends 550 km (342 miles) across southern Germany, connecting the Roman frontiers on the middle Rhine and upper Danube Rivers. It runs through farmland, forests, villages, and towns, and up onto the heights of the Taunus and Wetterau hills. Hadrian’s Wall is 117 km (73 miles) long, crossing the northern part of England from the Irish Sea to the North Sea. While portions of Hadrian’s Wall run through urban Newcastle and Carlisle, its central courses traverse open landscapes removed from modern settlements. The frontiers of the Roman Empire in northwestern Europe in the period AD 120–250. For a brief period around AD 138–160, Roman forces in Britain established and maintained a boundary far- ther north, the Antonine Wall. The frontier zones, indicated here by oblique hatching, are regions in which intensive interaction took place between the Roman provinces and other European peoples. -

The Development of the Mural Frontier in Britain from Hadrian to Caracalla* by David J

The Development of the Mural Frontier in Britain from Hadrian to Caracalla* by David J. Breeze and Brian Dobson In 1936 in a short paper in the Journal of Roman Studies,1 Sir lan Richmond effectively demonstrated tha Antonine th t frontiery t 'ato e no t actuallWals bu ' wa l y embodied structural advances ove s Hadrianiit r c predecessor somd an , e year sRomans latehi n i r Britain gave h 2 e briea t concisbu f e accoun improvemente th f o t s introduce Antonine th y db e planners inte oth later Wall developmene Th . resula s ta experiencf to murae th f eo l barrier from Hadria Carao nt - calla has, however, never been examined in detail: the purpose of this paper is to study this development. Hadrian's Wall, from the start of building in the early 120s to its abandonment when the Antonine earl e Walbuils th ywa n l ti 140s, underwent several modifications. When first planned the units closesfrontiee th o t Romaf ro n Britain appea havo rt e been accommodate seriea n di s of forts base Agricola'n do s road from Carlisl Corbridgeo et Stanegatee th , lina ,f com o e - munication through one of the few convenient east-west gaps.3 The forts were at half the normal interval of one day's march, allowing the rapid assembly of a force to meet an attack on whatever scale or to go on the offensive, striking up from Corbridge or Carlisle. Beyond the road to the west Kirkbride - and possibly Drumburgh4-may have housed units to control the localpopulation guard an Solwaye d th ease newle th th t o t ;y discovered for t Whickhaa t havy mma e formed part of a system of protection of the south bank of the Tyne, unbridged below Corbridge. -

'EXCAVATION of CASTLECAEY FORT on the ANTONINE VALLUM. PART I.-HISTORY and GENERAL DESCRIPTION. the Attention of the Society

EXCAVATIO F CASTLECAEO N E ANTONJNY TH FOR N O T E VALLUM1 27 . IV. 'EXCAVATION OF CASTLECAEY FORT ON THE ANTONINE VALLUM. PART I.-HISTORY AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION. B. CHEISTISONYD , SECRETARY. The attentio e Societth f no y having been e riscalle f publith o k o t d c works being erected clos Castlecaro et y Fort e Councith , l resolved that, continuancn i theif eo r investigation f Romao s n sites nexe th , t woro kt be undertaken should be there. Permission to excavate having been freely granted by Lord Zetland, the proprietor of the ground, and every facility given by Mr Charles -Brown, the factor, the direction of the CunninghamH. wor committe J. kwas Mr dto Thoma ,Mr C.E.and s, Boss, architect. Mr Mungo Buchanan again volunteered to fill the arduous post of surveyor; and with Mr Alexander Mackie as clerk of works, an efficient staff was made up, every member having had a large •experience in conducting operations of the kind. As previously, not more than two or three workmen were usually employed at a time, in order to ensure a strict supervision of the output. Ground was broken •early in March 1902, and the work proceeded, with but little interrup- tion froweatherd mba , tilfollowine th l g November. Position of the Fort.—The Roman fort of Castlecary, so named, perhaps, fro anciene mth t kee f Castlecaro p y s situatei nea , it r d about six miles west of Falkirk. Remains of eight forts on the line of the Antonine Vallue th mo t f stilonle o wese lon yd th f exisitan o t,o t t «ast. -

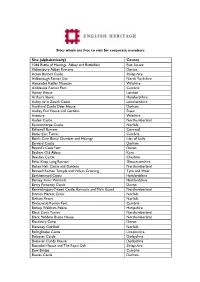

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Military Defeats, Casualties of War and the Success of Rome

MILITARY DEFEATS, CASUALTIES OF WAR AND THE SUCCESS OF ROME Brian David Turner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved By: Advisor: Prof. R. J. A. Talbert Prof. F. Naiden Prof. D. M. Reid Prof. J. Rives Prof. W. Riess Prof. M. T. Boatwright © 2010 Brian David Turner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BRIAN DAVID TURNER: Military Defeats, Casualties of War and the Success of Rome (Under the direction of Richard J. A. Talbert) This dissertation examines how ancient Romans dealt with the innumerable military losses that the expansion and maintenance of their empire demanded. It considers the prose writers from Polybius (c. 150 B.C.E.) through Dio Cassius (c. 230 C.E.), as well as many items from the material record, including triumphal arches, the columns of Trajan and Marcus, and other epigraphic and material evidence from Rome and throughout the empire. By analyzing just how much (or how little) the Romans focused on their military defeats and casualties of war in their cultural record, I argue that the various and specific ways that the Romans dealt with these losses form a necessary part of any attempt to explain the military success of Rome. The discussion is organized into five chapters. The first chapter describes the treatment and burial of the war dead. Chapter two considers the effect war losses had on the morale of Roman soldiers and generals. -

Hadrian's Wall: a Study in Function Mylinh Van Pham San Jose State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SJSU ScholarWorks San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Fall 2014 Hadrian's Wall: A Study in Function Mylinh Van Pham San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Pham, Mylinh Van, "Hadrian's Wall: A Study in Function" (2014). Master's Theses. 4509. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.u8sf-yx2w https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HADRIAN’S WALL: A STUDY IN FUNCTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Mylinh V. Pham December 2014 2014 Mylinh V. Pham ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled HADRIAN’S WALL: A STUDY IN FUNCTION by Mylinh V. Pham APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY December 2014 Dr. Jonathan Roth Department of History Dr. John Bernhardt Department of History Dr. Elizabeth Weiss Department of Anthropology ABSTRACT HADRIAN’S WALL: A STUDY IN FUNCTION by Mylinh V. Pham Earlier studies on Hadrian’s Wall have focused on its defensive function to protect the Roman Empire by foreign invasions, but the determination is Hadrian’s Wall most likely did not have one single purpose, but rather multiple purposes. -

The North-West Frontier of the Roman Empire

Frontiers of the Roman Empire inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2005 Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site Hadrian’s Wall Interpretation Framework Primary Theme: The north-west frontier of the Roman Empire HADRIAN’S WALL COUNTRY Interpretation Framework Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site Hadrian’s Wall Interpretation Framework Primary Theme: The north-west frontier of the Roman Empire Genevieve Adkins and Nigel Mills Cover image Event at Segedunum © Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums i Interpretation Framework Published by Hadrian’s Wall Heritage Limited East Peterel Field Dipton Mill Road Hexham Northumberland NE46 2JT © Hadrian’s Wall Heritage Limited 2011 First published 2011 ISBN 978-0-9547342-4-4 Typeset by Printed and bound in Great Britain by Campbell & Co Farquhar and Son Ltd Edinburgh Perth EH9 1NR PH2 8HY ii Interpretation Framework Foreword v 1 Introduction – recognising the need for change 2 2 An Interpretation Framework for Hadrian’s Wall – establishing a framework for change 2.1 Hadrian’s Wall – "the north-west frontier of the Roman Empire" 4 2.2 Why an interpretation framework? 6 2.3 What is interpretation and how can it help? 6 2.4 Creating visitor experiences 6 2.5 The benefits of good interpretation 7 2.6 Audience development 7 2.7 Purpose of the Interpretation Framework 8 3 The audiences for Hadrian’s Wall 3.1 The existing audiences 10 3.2 The potential audiences 10 3.3 Audience knowledge and perceptions of Hadrian’s Wall 11 3.4 Key findings from research 12 3.5 What visitors want and need