University of Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Woman for Women in Bengal

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Vol. III. Issue. IV 1 December 2012 The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Rokeya’s Reverse Thoughts: Sketch of Male Characters in Sultana’s Dream Md. Mohoshin Reza Assistant Professor, Department of English Bangladesh University of Business and Technology (BUBT) Rupnagar, Mirpur 2, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract: Characters of the male folk in Rokeya’s Sultana’s Dream impart images of men with no human characteristics and tendencies. They only physically resemble as humans but are indeed idle, unpunctual, arrogant, selfish, dominating and fanatic to customs and convention and most of all, anti woman in attitude. They are, egocentric, dominating, and scornful to women. But things turn reverse and the entire male folk come to be terribly avenged in the story of Sultana’s Dream. Finally, they come to wear the shackles of Purdah and remain confined to Murdana (Seclusion) as the same way as they did to women. 1 Introduction Rokeya (1887-1947 A.D) is considered to be the visionary emancipator of women in Bengal (presently Bangladesh). The core inspiration of her literary works rests in her realization of the needs of taking measures against the suppression, oppression and domination of men over the women race for centuries in Bengal (Alam, 1992: 55). Her mission of sowing the seeds of self strength in the mind of Bengal’s women has always been underlying in her literary works. Sultana’s Dream is one of her distinguished literary pieces in English. -

1 Introduction

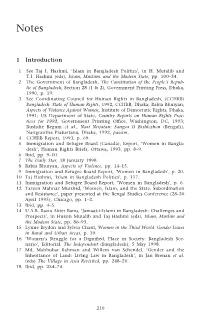

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

Toward a Definitive Grammar of Bengali - a Practical Study and Critique of Research on Selected Grammatical Structures

TOWARD A DEFINITIVE GRAMMAR OF BENGALI - A PRACTICAL STUDY AND CRITIQUE OF RESEARCH ON SELECTED GRAMMATICAL STRUCTURES HANNE-RUTH THOMPSON Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD SOUTH ASIA DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES LONDON O c t o b e r ZOO Laf ProQuest Number: 10672939 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672939 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis is a contribution to a deeper understanding of selected Bengali grammatical structures as far as their syntactic and semantic properties are concerned. It questions traditional interpretations and takes a practical approach in the detailed investigation of actual language use. My methodology is based on the belief that clarity and inquisitiveness should take precedence over alliance to particular grammar theories and that there is still much to discover about the way the Bengali language works. Chapter 1 This chapter on non-finite verb forms discusses the occurrences and functions of Bengali non-finite verb forms and concentrates particularly on the overlap of infinitives and verbal nouns, the distinguishing features between infinitives and present participles, the semantic properties of verbal adjectives and the syntactic restrictions of perfective participles. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Tagore, the Home and the World

Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare Baire (Bengali, 1915) / The Home and the World (1919) EN123, Modern World Literatures Lecture: Week 1, Term 2 Dr. Divya Rao ([email protected]) Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) • Man of Letters, Nobel Prize (1913) • Modernist | Humanist | Internationalist • Viswa Bharati University (1921) – a radical experiment in education • Benevolent Paternalist: elite, upper-caste, upper-class Bengali family; landed gentry that combined traditional zamindari (‘landlordism’) with modern education and progressive ideals and politics • Renounced knighthood in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (1919) The Indian Empire in 1907. From Charles Joppen, Historical Atlas of India for the Use of High Schools, Colleges, & Private Students (London, Longmans, Green & Co., 1907), No. 26. [Source: Wikipedia] Partition of Bengal in 1905. The western part (Bengal) gained parts of Odisha, the eastern part (Eastern Bengal and Assam) regained Assam that had been made a separate province in 1874 Historical Context • 1905, Lord Curzon’s Partition of Bengal (‘divide and rule’) • The crystallisation of Hindu- Muslim communal division: which sets off a series of major historical repercussions thereafter (and felt even today) • 1905-1908: Swadeshi movement—sees both reformists and revolutionaries; moderates and extremists • Boycott of foreign goods; emphasis on economic self- reliance The Home and the World (‘Ghare Baire’) • 1915-1916: appears in the serialised form in avant- garde journal Sabuj Patra (‘Green Leaves’) • 1919: translated into English by Tagore’s nephew (in consultation with Tagore) Surendranath Tagore • Intersections of: Home | Nation | World with that of Tradition | Modernity • Colloquial Cholito-bhasha (‘running language’) preferred to Sanskritised Sadhu-bhasha (‘uptight language’) Influences on the Novel • Auguste Comte (1798-1857): French philosopher and social scientist; formulated the doctrine of positivism. -

'War, Violence and Rabindranath Tagore's Quest for World Peace

War, Violence and Rabindranath Tagore’s Quest for World Peace1 Mohammad A. Quayum International Islamic University Malaysia Abstract Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), India’s messianic poet and Asia’s first Nobel Laureate (1913), promulgated a vision of peace through the cultivation of the ideologies of Ahimsa, or non-violence, which he derived from the Bhagavad Gita and Advita, or one-identity of the universe, which he derived from the Upanishads. This paper investigates how Tagore formulated this vision of peace against a backdrop of and as an antidote to the reckless ‘jihadism’ (both religious and secular) and ‘war-madness’ of the twentieth century, which witnessed the two World Wars as well as an on-going violence in different forms, effectively turning the world into a ‘tower of skulls.’ He attributed this ‘devil dance of destruction’ to three intersecting forces: the unmediated materialism of modern society; belligerent nationalism which often led to nationalist selfishness, chauvinism and self- aggrandisement; and the machinery of organised religion which, he said, ‘obstructs the free flow of inner life of the people and waylays and exploits it for the augmentation of its own power.’ His response to it was the creation of a global human community, or a ‘grand harmony of all human races,’ by shunning exclusivism and dogmatism of all forms, and through the fostering of awareness that human beings were not only material and rational as creatures but also moral and spiritual, sharing a dew-drop of God in every soul. * * * * * In July 1955, Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein issued a joint manifesto, asking humanity to shun the path of conflicts and war and save the species from an impending doom. -

Chalantika : Strategies of Compilation Md

iex›`ª wek¦we`¨vjq cwÎKv \ msL¨v : 2 \ kir 1427 Chalantika : Strategies of Compilation Md. Mainul Islam* [Abstract : Chalantika (1930) Dictionary was published at a time when many Bangla dictionaries, large and small, were readily available. Despite having such a large number of dictionaries, Rajshekhar Basu realized the lack of a handy and at a time effective dictionary. So he decided to compile such a dictionary which will help much the readers who faces trouble reading modern literature. To meet the objectives Rajshekhar Basu followed some special strategies in the Compilation of Chalantika.This paper is concerned almost exclusively with the process and techniques of compilation applied in Chalantika] Key words : Lexicography, Compilation, Entry, Orthography, Synonym, Appendix. The effects of the Renaissance in the nineteenth century that were observed on education, social development, study of native culture etc. in British India became much clearer in the next century. Along with other sectors, many positive changes and developments were noticed in the study of language and literature. Study of Bangla Lexicography moved a step forward in twentieth century. The most important and mentionable achievement for this sector is that, native lexicographers took several initiatives to compile Bangla Dictionary and showed profound skill in their works. Names of some native lexicographers who have played a leading role in the twentieth century are : Jogesh Chandra Ray Vidyanidhi (Bangala Sabdakosh, 1903), Subal Chandra Mitra (Saral Bangala Abhidahan, 1906), Janendra Mohan Das (Bangala Bhashar Abhidhan, 1917), Rajshekhar Basu (Chalantika, 1930) Haricharan Bandopadhayaya (Bangiya Sabdakosh, 1932), Ashu Tosh Dev (1938), Kazi Abdul Wadud (Byabaharik Sabdakosh, 1953), Sailendra Biswas (Samsad Bangla Abhidhan, 1955), Muhammad Enamul Haque & Shibprosanna Lahiri (Byabaharik Bangla Abhidhan, 1974 & 1984), Ahmed Sharif (Sangkhipta Bangla Abhidhan, 1992), Abu Ishaque (Bangla Academy Samakalin Bangla Bhashar Abhidhan, 1993) et al. -

Family, School and Nation

Family, School and Nation This book recovers the voice of child protagonists across children’s and adult literature in Bengali. It scans literary representations of aberrant child- hood as mediated by the institutions of family and school and the project of nation-building in India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The author discusses ideals of childhood demeanour; locates dissident children who legitimately champion, demand and fight for their rights; examines the child protagonist’s confrontations with parents at home, with teachers at school and their running away from home and school; and inves- tigates the child protagonist’s involvement in social and national causes. Using a comparative framework, the work effectively showcases the child’s growing refusal to comply as a legacy and an innovative departure from analogous portrayals in English literature. It further reviews how such childhood rebellion gets contained and re-assimilated within a predomi- nantly cautious, middle-class, adult worldview. This book will deeply interest researchers and scholars of literature, espe- cially Bengali literature of the renaissance, modern Indian history, cultural studies and sociology. Nivedita Sen is Associate Professor of English literature at Hans Raj College, University of Delhi. Her translated works (from Bengali to English) include Rabindranath Tagore’s Ghare Baire ( The Home and the World , 2004) and ‘Madhyabartini’ (‘The In-between Woman’) in The Essential Tagore (ed. Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarty, 2011); Syed Mustafa Siraj’s The Colo- nel Investigates (2004) and Die, Said the Tree and Other Stories (2012); and Tong Ling Express: A Selection of Bangla Stories for Children (2010). She has jointly compiled and edited (with an introduction) Mahasweta Devi: An Anthology of Recent Criticism (2008). -

Colonialism & Cultural Identity: the Making of A

COLONIALISM & CULTURAL IDENTITY: THE MAKING OF A HINDU DISCOURSE, BENGAL 1867-1905. by Indira Chowdhury Sengupta Thesis submitted to. the Faculty of Arts of the University of London, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies, London Department of History 1993 ProQuest Number: 10673058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673058 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis studies the construction of a Hindu cultural identity in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries in Bengal. The aim is to examine how this identity was formed by rationalising and valorising an available repertoire of images and myths in the face of official and missionary denigration of Hindu tradition. This phenomenon is investigated in terms of a discourse (or a conglomeration of discursive forms) produced by a middle-class operating within the constraints of colonialism. The thesis begins with the Hindu Mela founded in 1867 and the way in which this organisation illustrated the attempt of the Western educated middle-class at self- assertion. -

Imagining “One World”: Rabindranath Tagore's Critique of Nationalism

Imagining “One World”: Rabindranath Tagore’s Critique of Nationalism Mohammad A. Quayum International Islamic University Malaysia Our mind has faculties which are universal, but its habits are insular. —Rabindranath Tagore Introduction In a poem entitled, “The Sunset of the Century,” written on the last day of the nineteenth century, India’s messianic poet and Asia’s first Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), launched a fierce diatribe on nationalism. In a mood of outrage and disenchantment, tempered with intermittent hope, he wrote: The last sun of the century sets amidst the blood-red clouds of the West and the whirlwind of hatred. The naked passion of the self-love of Nations, in its drunken delirium of greed, is dancing to the clash of steel and howling verses of vengeance. The hungry self of the Nation shall burst in a violence of fury from its shameless feeding. For it has made the world its food. And licking it, crunching it and swallowing it in big morsels, It swells and swells Till in the midst of its unholy feast descends the sudden shaft of heaven piercing its heart of grossness. (Nationalism 80) This anti-nationalitarian sentiment—that nationalism is a source of war and carnage; death, destruction and divisiveness, rather than international solidarity, that induces a larger and more expansive vision of the world— remains at the heart of Tagore’s imagination in most of his writings: his letters, essays, lectures, poems, plays and fiction. 1 He was always opposed to the nationalism of Realpolitik and hyper-nationalism that breathed meaning into Thucydides’s ancient maxim that “large nations do what they wish, while small nations accept what they must” (qtd. -

India's Struggle for Independence 1857-1947

INDIA’S STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1857-1947 BIPAN CHANDRA MRIDULA MUKHERJEE ADITYA MUKHERJEE K N PANIKKAR SUCHETA MAHAJAN Penguin Books CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. THE FIRST MAJOR CHALLENGE: THE REVOLT OF 1857 2. CIVIL REBELLIONS AND TRIBAL UPRISINGS 3. PEASANT MOVEMENTS AND UPRISINGS AFTER 1857 4. FOUNDATION OF THE CONGRESS: THE MYTH 5. FOUNDATION OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS: THE REALITY 6. SOCIO-RELIGIOUS REFORMS AND THE NATIONAL AWAKENING 7. AN ECONOMIC CRITIQUE OF COLONIALISM 8. THE FIGHT TO SECURE PRESS FREEDOM 9. PROPAGANDA IN THE LEGISLATURES 10. THE SWADESHI MOVEMENT— 1903-08 11. THE SPLIT IN THE CONGRESS AND THE RISE OF REVOLUTIONARY TERRORISM 12. WORLD WAR I AND INDIAN NATIONALISM: THE GHADAR 13. THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT AND ITS FALLOUT 14. GANDHIJI‘S EARLY CAREER AND ACTIVISM 15. THE NON-COOPERATION MOVEMENT— 1920-22 16. PEASANT MOVEMENTS AND NATIONALISM IN THE 1920’S 17. THE INDIAN WORKING CLASS AND THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT 18. THE STRUGGLES FOR GURDWARA REFORM AND TEMPLE ENTRY 19. THE YEARS OF STAGNATION — SWARAJISTS, NO-CHANGERS AND GANDHIJI 20. BHAGAT SINGH, SURYA SEN AND THE REVOLUTIONARY TERRORISTS 21. THE GATHERING STORM — 1927-29 22. CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE— 1930-31 23. FROM KARACHI TO WARDHA: THE YEARS FROM 1932-34 24. THE RISE OF THE LEFT-WING 25. THE STRATEGIC DEBATE 1935-37 26. TWENTY-EIGHT MONTHS OF CONGRESS RULE 27. PEASANT MOVEMENTS IN THE 1930s AND ‘40s 28. THE FREEDOM STRUGGLE IN PRINCELY INDIA 29. INDIAN CAPITALISTS AND THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT 30. THE DEVELOPMENT OF A NATIONALIST FOREIGN POLICY 31. THE RISE AND GROWTH OF COMMUNALISM 32. -

Professor KAZI DIN MUHAMMAD (B

http://www.bmri.org.uk Professor KAZI DIN MUHAMMAD (b. 1927- d. 2011) I have been aware of Kazi Din Muhammad since my youth. I first became familiar with his name as early as 1958 when I read a book of humorous anecdotes titled “Golak Chandrer Antmakatha” (Autobiography of Golak Chandra). As a young student, I found the book very funny and hilarious. The author of this book was born in the district Faridpur (circa 1906), but many years later when I asked Dr Kazi Din Muhammad whether he was the author of that book, he revealed that it was, in fact, written by another Kazi Din Muhammad who was also a prominent writer. Long time after I left Alokdihi Jan Bakhsh High English School in Dinajpur, I heard Kazi Din Muhammad’s name again, thanks to late Professor Mufakhkharul Islam, who taught Bengali Literature at Carmichael College, Rangpur. He told me that he was a classmate of Kazi Din Muhammad in the Department of Bangla at Dhaka University in the late 1940s. He remembered him affectionately, as both of them had studied for their Master’s Degree (MA) in Bengali Literature at Dhaka University in 1949. When the Examination results were published, Kazi Din Muhammad was awarded First Class First Degree and Mufakhkharul Islam had received a Second Class First. They remained good friends and held each other in high regard. In fact, both of them became very prominent scholars of Bengali Literature. When I had an opportunity to speak to Professor Kazi Din Muhammad in 2006, he confirmed that he was indeed a classmate of Mufakhkharul Islam at Dhaka University.