Copyright by Raymond Joseph Parrott 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Won't Buy All Books

The Courier Volume 4 Issue 31 Article 1 6-4-1971 The Courier, Volume 4, Issue 31, June 4, 1971 Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First CD nursing Nearly 700 class graduates to graduate The fourth commencement College of DuPage will graduate Berg, college president, was the exercises of College of DuPage will its first class of nurses at next speaker. be Friday evening, June 11, at 7:45 week’s commencement exercises. Mrs. Santucci said she is urging in the college gym. About 650 Twenty eight nurses, one of them the students to work in general Associate degrees and about 50 male, will graduate and after hospitals for wide experience certificates in various technologies taking a state board examination before specializing. will be awarded. qualify as registered nurses. The class that was “pinned” Dr. Rodney Berg, college Mary Ann Santucci, chairman of includes: president, will introduce the stage the nursing program, presented Susan Altorfer, Carol Beechler, party and the speakers of the pins to the class at a meeting May Betty Black, Patricia Crandall, evening. Thomas Biggs, president 16 in the Gymnasium. Dr. Rodney Betty Crim, Donna Dorrough, of the Associated Student Body, Noreen Ehlenburg, Gloria Ellis, will make remarks. Phyllis Foster, Denise Gilman, The main speaker of the evening Diane Hastings, Carol Jenkins, will be Dr. -

Reconstructing Democracy

Reconstructing Democracy Joint Report of Independent Electoral Monitors of Haiti’s November 28, 2010 Election Let Haiti Live Organizations listed indicate participants in November 28th observer delegation Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Credibility and Timing of November 28, 2010 Election The CEP and Exclusions Without Justification Inadequate Time to Prepare Election Election in the Midst of Crises The Role of MINUSTAH III. Observations of the Independent Monitors IV. Responses from Haiti and the International Community Haitian Civil Society The OAS and CARICOM The United Nations The United States Canada V. Conclusions APPENDICES A. Additional Analysis of the Electoral Law B. Detailed Observation from the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti Team C. Summary of Election Day 11/28/10, The Louisiana Justice Institute, Jacmel D. Observations from Nicole Lazarre, The Louisiana Justice Institute, in Port-au-Prince E. Observations from Alexander Main, Center for Economic and Policy Research F. Observations from Clay Kilgore, Kledev G. Voices of Haiti: In Pursuit of the Undemocratic, Mark Snyder, International Action Ties H. U.S. Will Pay for Haitian Vote Fraud, Brian Concannon and Jeena Shah, IJDH Executive Summary The first round of Haiti’s presidential and legislative election was held on November 28, 2010 in particularly inauspicious conditions. Over one million people who lost their homes in the earthquake were still living in appalling conditions, in makeshift camps, in and around Port-au- Prince. A cholera epidemic that had already claimed over two thousand lives was raging throughout the country. Finally, the election was being organized by a provisional electoral authority council that was hand-picked by President Préval and widely distrusted. -

Between Power and Vulnerability

THE SMALLNESS OF SMALL STATES: BETWEEN POWER AND VULNERABILITY Happy Tracy Stephanie1 Abstract This essay examines the power of small states in global development diplomacy. This essay seeks to address the following things. The power and obstacles of small states in global development diplomacy, how small states can increase their power, and the limitations of small state diplomacy. The most important part of this essay is the analysis related to the strategies to increase the power of small states. This essay argues that the sources of power of small states in global development diplomacy are the rise of non-traditional issues and their inherent resilience. Moreover, small states can use strategies of coalition building, issue prioritisation, and agenda setting to increase their power in global negotiations through intergovernmental organisations, focusing on the United Nations. Keywords: diplomacy, small states, power, vulnerability Introduction About two-thirds of the United Nations (UN) members are small states (https://www.diplomacy.edu/small-states-diplomacy). According to Diana Panke (2012, 316), a small state is a "state with less than average financial resources in a particular negotiation setting.” Just like their bigger counterparts, small states pursue the same interests of security, prosperity, and wellbeing of their citizens. They also conduct their diplomacy using the same diplomatic instruments as larger states. However, how small states conduct diplomacy attracts deep examinations because unlike bigger states, small states can experience some difficulties in conducting international negotiations due to limited budgets (Panke, 2012;317). In this essay, I shall argue that: First, the sources of power of small states in global development diplomacy are the rise of non-traditional issues and their inherent resilience. -

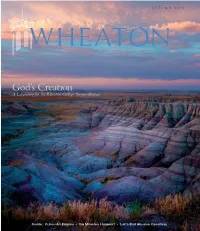

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

Wheaton Athletes Worldwide

WH E A WHEATON T O N 21 INNOVATORS | COMMUNISM TO CHRIST | JIM HEIMBACH '78 | STUDENT DEBT REAR ADMIRAL R. TIMOTHY ZIEMER '68, P.46 USN (RET.) VOLUME 2015 ISSUE 18 3 // // AUTUMN 2015AUTUMN 21 Innovators in the 21st Century WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE Student Debt: Why It’s Worth It From Communism to Christ KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT WHEATON? TELL US! As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to recruit to the College. You have a unique understanding of Wheaton and can easily identify the type of students who will take full advantage of the Wheaton College experience. We value your opinion and invite you to join us in the recruit- ment process. Please send contact information of potential students you believe will thrive in Wheaton’s rigorous and Christ-centered academic environment. We will take the next step to connect with them and begin the process. 800.222.2419 x0 wheaton.edu/refer VOLUME 18 // ISSUE 3 AUTUMN 2015 featuresWHEATON “ I consider my work a success if I can provide a showcase of God’s creation with my creation.” ➝ Facebook facebook.com/ 21 INNOVATORS: ART: wheatoncollege.il LEADING THE JIM HEIMBACH ’78 WAY / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege COMMENCEMENT: STUDENT DEBT: GOD’S DOUBLE WHY IT’S WORTH IT Instagram AGENT 30 34 instagram.com/ / / wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE THE WHEATON FUND + YOU IT ALL ADDS UP TO A BIG DIFFERENCE households gave to 6,650 the Wheaton Fund 75 households gave $10,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund 635 households made a first-time Wheaton Fund gift 5 households gave $100,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund $814,614.85 given by those who gave less than $1,000 to the Wheaton Fund 58.55% of dollars came from alumni 26.57% of dollars came from parents 14.88% of dollars came from friends Numbers included here represent giving through June 10, 2015 Thank you for all you did to make fiscal year 2015 successful! Make your Wheaton Fund gift today to help get fiscal year 2016 off to a strong start. -

Danielle De St. Jorre Scholarship

THE INTERNATIONAL OCEAN INSTITUTE announces the DANIELLE DE ST. JORRE SCHOLARSHIP Call for Applications In memory of Danielle de St. Jorre, applications and nominations are invited for a scholarship to help fund the participation of a woman from a Small Island Developing State in IOI’s training programme on Ocean Governance: Policy, Law and Management, to be held from 20th May to 17th July 2020 at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. See: http://internationaloceaninstitute.dal.ca/training.html. Application deadline: 10th February 2020 The International Ocean Institute (IOI) was founded in 1972 by Elisabeth Mann Borgese as an international, non-governmental, non-profit organisation. Headquartered in Malta under an agreement with the Government of Malta, the institute has a twofold mission: • to ensure the sustainability of the Ocean as “the source of life”, and to uphold and expand the principle of the common heritage as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; • to promote the concept of Pacem in Maribus (peace in the Oceans) and its management and conservation for the benefit of future generations. Since 2000 the IOI has awarded an annual scholarship to one woman from a Small Island Developing State (SIDS) who is involved in marine related activities to improve her knowledge of the subject through relevant training or university studies. This scholarship was established to honour the memory of the late Danielle de St. Jorre, Minister for Foreign Affairs, the Environment and Tourism of the Republic of the Seychelles and a member of the IOI Governing Board, in consideration of all she did in her short life for the benefit of her country, the small island developing states and the world at large. -

Pygmalion Scheduled (Or March 12,13,14

Friday, March 6, 1964 ECHO TAYLOR UNIVERSITY — UPLAND, INDIANA VOL. XLIV —NO. 9 George B. Shaw's "Pygmalion Scheduled (or March 12,13,14 Pygmalion, a full length play by transformation, approved of the 12th 13th and 14th. George Bernard Shaw, will be pre project as a scientific experiment, The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, sented at Taylor on March 12, 13, but did not agree with the inhu is portrayed by Marilyn Domhoff; and 14 at 8:15 in Shreiner Audi man treatment that Higgins gave Professor Higgins is played by torium. out to Eliza. Pickering is as intelli Bob Finch; and Colonel Pickering, Mr. Shaw wrote the play to im gent as Higgins, but he has man Higgin's Phonetician cohort, is press upon the public the impor ners becoming a gentleman, which portrayed by Tom Allen. are quite conspicious in Higgins tance of phoneticians in modern The other members of the cast by their absence. day society. include Cliff Robertson, Marion Pickering observes that Higgins Dodd, Eleanor Hustwick, Margo The plot involves Henry Hig- has brought Eliza up from one Dryer, Darlene Young, Ann Lentz, gins, an English speech teacher, grade of living in the direction of Dale Dickey, Gale Strain, and Bob who attempts to transform a Bob Finch, Eleanor Hustwick, and Tom Allen practice a scene another and in the process has Finton. cockney flower girl, Eliza Doo made her unfit for both lives. for the Trojan Player's production of Pygmalion. little, into an English lady by Tickets for the play may be Higgins thinks of himself as a teaching her to speak cultivated purchased prior to the date of very sufficient man until the hand English. -

World Justice Forum Worldworking Togetherjustice to Advance the Ruleforum of Law

World Justice Forum WorldWorking TogetherJustice to Advance the RuleForum of Law July 2-5, 2008 Vienna, Austria Tble of Contents Tbletable of of Contentscontents Welcome Letters Founder’s Welcome 5 Mayor’s Welcome 7 World Justice Project Overview 8 Honorary Chairs 10 Co-Sponsors 11 Financial Supporters 12 Forum Agenda 15 Maps Austria Center Vienna 44 City Of Vienna 48 Underground Metro 49 Special Thanks 50 Useful Information 53 Notes 69 Welcome to the InauguralWelcome World Justice Forum Every nation and culture has universal aspirations: we want communities that are safe, prosperous, just, healthy and educated. The rule of law is essential to achieving these goals. Over the next three days, leaders from around the world representing many disciplines will forge new partnerships and design programs to advance the rule of law in our communities. The World Justice Forum brings us together around our shared belief in two complementary premises. First, the rule of law is the foundation for communities of opportunity and equity. Second, collaboration across disciplines is the most effective way to advance the rule of law and fulfill our hopes for society. This Forum depends upon the support of the World Justice Project’s distinguished honorary chairs, sponsors and funders. I thank them for their contributions to this effort. Each of you can play a key role in launching a multinational, multidisciplinary movement to advance the rule of law. It is essential that the Forum serve as an incubator of new programs to advance the rule of law in our respective communities. I look forward to working with you in the days ahead. -

Interview with Bob Van Lierop

Interview with Bob Van Lierop "[Our film A Luta Continua ] was smuggled into Portugal by Frelimo. They used it there. It was also smuggled into South Africa. And prior to the Soweto uprising it was shown by the Black Consciousness Movement and others in South Africa. And they began to use some of the slogans-a luta continua [the struggle continues], which was, of course, as you know, the way Eduardo [Mondlane] always signed his letters." - Bob Van Lierop Introduction Bob Van Lierop doesn't know how many copies of his film A Luta Continua were made, or how many times it was shown. And it is probably impossible to track exactly how much influence it had in making the Portuguese-language slogan from the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo) a rallying cry in South Africa and for allied movements around the world. But there is no doubt that for many in North America and Europe it provided the definitive visual imagery that made identification with African liberation struggles come alive in the 1970s. This short film portraying Mozambican guerrillas fighting against Portuguese colonialism was filmed in 1971 and was widely distributed throughout the 1970s. A sequel, O Povo Organizado , was filmed shortly after Mozambique's independence in 1975 and released in 1976. Bob Van Lierop, who produced these two films which deeply impacted black independent cinema in the United States in this period, was not a filmmaker by training. He was a progressive African American lawyer based in New York who launched the project in solidarity with Frelimo, and decided to do the film himself when he was unable to locate a filmmaker willing to take on the task. -

Decentering the Dictator: 'In the Time of the Butterflies' and the Mirabal Sisters' Outspoken Challenge

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive English Honors College Spring 5-2019 Decentering the Dictator: ‘In the Time of the Butterflies’ and the Mirabal Sisters’ Outspoken Challenge Elise Coombs University at Albany, State University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_eng Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Coombs, Elise, "Decentering the Dictator: ‘In the Time of the Butterflies’ and the Mirabal Sisters’ Outspoken Challenge" (2019). English. 26. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_eng/26 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in English by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Decentering the Dictator: ‘In the Time of the Butterflies’ and the Mirabal Sisters’ Outspoken Challenge An honors thesis presented to the Department of English, University at Albany, State University of New York, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in English and Graduation from the Honors College Elise Coombs Directed by Professor Paul Stasi, English Second Reader: Professor Laney Salisbury, Journalism May 2019 Abstract Julia Alvarez’s portrayal of the Mirabal sisters from In the Time of the Butterflies centers the novel around the sisters’ speech and humanity. This decenters the dictator, a figure who was often central to Latin American dictator novels. The first chapter will provide background on the dictator’s characteristics to demonstrate how the Mirabal sisters’ speech draws attention away from his power. -

1 ALAN BJERGA: Good Afternoon, and Welcome to the National Press

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB SPEAKERS PRESS CONFERENCE WITH RAYMOND JOSEPH SUBJECT: HAITI: RECOVERY EFFORTS AND OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE MODERATOR: ALAN BJERGA, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB HOLEMAN LOUNGE, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2010 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. ALAN BJERGA: Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club for our Speakers Press Conference. My name is Alan Bjerga. I'm a reporter at Bloomberg News and President of the National Press Club. We're the world’s leading professional organization for journalists, and we are committed to the future of journalism by providing informative programming and journalism education and by fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. And on behalf of our members, I'd like to welcome our speaker and our guests in the audience today, as well as those who may be watching on television. We're looking forward to today’s speech and afterwards, I will ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. But first, a few words about our speaker. -

Program Pages

The Lincoln Academy of Illinois 49th Annual Convocation and Investiture of Laureates Saturday, the thirteenth day of April Two thousand thirteen Centennial Hall Augustana College Rock Island, Illinois Lincoln appreciated the power of ‘living histories’ as a source of wisdom and inspiration for future generations. The Lincoln Academy of Illinois was created to recognize the living histories of those who walk among us believing, as Lincoln did, that those living histories remind future generations of the endless possibilities ahead. We gather to recognize the living histories of our time – individuals who exemplify the highest ideals of their respective callings, whose lives and contributions to society perpetuate the complete spectrum of human endeavor. They are the ‘Lincoln hearted’ people among us. Dr. Thomas F. Schwartz Illinois State Historian 1993-2011 The Lincoln Academy of Illinois Introductory Music The Ascension Chapel Ringers, directed by Larry Peterson Call to Order James Gidwitz Regent of the Academy Processional* The Academic Trustees, Rectors, General Trustees, Regents, Regents for Life, Laureates, Clergy, Officers of the Academy and the Governor of the State of Illinois Festmarsch from Wagner‟s Tannhäuser, orchestrated by Robert W. Rumbelow The Augustana Symphonic Band, directed by Dr. James Lambrecht Presentation of the Colors* Sergeant Joshua Brown, USAR; Specialist John Daniel Engelhardt, USAR; Officer Candidate William Bredberg, USMC; and Officer Candidate Alex Kurian, USMC The National Anthem* Invocation* The Reverend Richard Priggie Chaplain, Augustana College Opening of the Convocation The Chancellor Illinois Arranged by Andrew Boysen The Augustana College Symphonic Band, directed by Dr. James Lambrecht The Augustana Choir, directed by Dr. Jon Hurty The Lincoln Academy of Illinois Decoration of Laureates Brenda C.