Decentering the Dictator: 'In the Time of the Butterflies' and the Mirabal Sisters' Outspoken Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hidden Value of House and Home an Analysis of the Social And

Ivy Fredriksson Örebro University Department of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences English The Hidden Value of House and Home An analysis of the social and physical setting in The House on Mango Street Author: Ivy Fredriksson C-essay Autumn 2015 Supervisor: Dr Anna Linzie 0 Ivy Fredriksson Abstract The goal of this essay is to establish what influence the social and physical setting in the novel The House on Mango Street, written by Sandra Cisneros, has on the value of house and home for the protagonist. The thesis of this essay is that the meaning and value of house and home, upon the discovery and acceptance of social identity, evolve and change from a negative and dependent impression to a positive and independent one for the protagonist. The analysis of the social and physical setting, based on close reading, helps to determine and monitor the value of home throughout the entire novel, including the final value of home to the protagonist. 1 Ivy Fredriksson Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Background …………………………………………………………………………... 5 Analysis ……………………………………………………………………………...... 9 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………… 17 Works Cited ………………………………………………………………………….. 19 2 Ivy Fredriksson Introduction What is the meaning of home? The place which a person calls home is usually the place where he or she lives, but that does not guarantee a sense of belonging. A house is a physical or material home, while a “real home” may be seen as the psychological living space, where a person will feel that he or she belongs, or “a home in the heart”. Historically, a home or domestic space often occupies the core of many novels, as it still does today. -

Won't Buy All Books

The Courier Volume 4 Issue 31 Article 1 6-4-1971 The Courier, Volume 4, Issue 31, June 4, 1971 Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First CD nursing Nearly 700 class graduates to graduate The fourth commencement College of DuPage will graduate Berg, college president, was the exercises of College of DuPage will its first class of nurses at next speaker. be Friday evening, June 11, at 7:45 week’s commencement exercises. Mrs. Santucci said she is urging in the college gym. About 650 Twenty eight nurses, one of them the students to work in general Associate degrees and about 50 male, will graduate and after hospitals for wide experience certificates in various technologies taking a state board examination before specializing. will be awarded. qualify as registered nurses. The class that was “pinned” Dr. Rodney Berg, college Mary Ann Santucci, chairman of includes: president, will introduce the stage the nursing program, presented Susan Altorfer, Carol Beechler, party and the speakers of the pins to the class at a meeting May Betty Black, Patricia Crandall, evening. Thomas Biggs, president 16 in the Gymnasium. Dr. Rodney Betty Crim, Donna Dorrough, of the Associated Student Body, Noreen Ehlenburg, Gloria Ellis, will make remarks. Phyllis Foster, Denise Gilman, The main speaker of the evening Diane Hastings, Carol Jenkins, will be Dr. -

Reconstructing Democracy

Reconstructing Democracy Joint Report of Independent Electoral Monitors of Haiti’s November 28, 2010 Election Let Haiti Live Organizations listed indicate participants in November 28th observer delegation Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Credibility and Timing of November 28, 2010 Election The CEP and Exclusions Without Justification Inadequate Time to Prepare Election Election in the Midst of Crises The Role of MINUSTAH III. Observations of the Independent Monitors IV. Responses from Haiti and the International Community Haitian Civil Society The OAS and CARICOM The United Nations The United States Canada V. Conclusions APPENDICES A. Additional Analysis of the Electoral Law B. Detailed Observation from the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti Team C. Summary of Election Day 11/28/10, The Louisiana Justice Institute, Jacmel D. Observations from Nicole Lazarre, The Louisiana Justice Institute, in Port-au-Prince E. Observations from Alexander Main, Center for Economic and Policy Research F. Observations from Clay Kilgore, Kledev G. Voices of Haiti: In Pursuit of the Undemocratic, Mark Snyder, International Action Ties H. U.S. Will Pay for Haitian Vote Fraud, Brian Concannon and Jeena Shah, IJDH Executive Summary The first round of Haiti’s presidential and legislative election was held on November 28, 2010 in particularly inauspicious conditions. Over one million people who lost their homes in the earthquake were still living in appalling conditions, in makeshift camps, in and around Port-au- Prince. A cholera epidemic that had already claimed over two thousand lives was raging throughout the country. Finally, the election was being organized by a provisional electoral authority council that was hand-picked by President Préval and widely distrusted. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

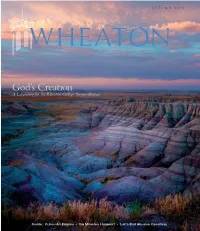

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

Julia Alvarez & Junot Díaz: the Formation of Boundaries In

JULIA ALVAREZ & JUNOT DÍAZ: THE FORMATION OF BOUNDARIES IN CREATING A NEW DOMINICAN-AMERICAN IDENTITY By VANESSA COLEMAN A capstone submitted to the Graduate School- Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Richard Drucker And approved by ____________________________________ Richard Drucker Camden, New Jersey October 2016 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT Julia Alvarez & Junot Díaz: The Formation of Boundaries in Creating a New Dominican-American Identity By VANESSA COLEMAN Capstone Director: Dr. Richard Drucker This essay will explore the concept of ethnicity in the stories and through the characters in the writings of Junot Díaz and Julia Alvarez. In particular, I will examine their critically acclaimed novels, Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) and Alvarez’s How the García Girls Lost Their Accents (1991), and how the authors’ personal lives are reflected in these novels. Through the novels, I will examine the acculturation of Dominicans immigrating to the United States and consider how their narratives relate to the idea of a new Dominican-American identity. I will analyze how displacement, economics, and national expectations affect the characters’ behaviors as they search for a new identity. Finally, I will evaluate, and corroborate with scholarship, the aspects of immigrants’ former lives, and how their past and present ethnic identities have transformed with their attempt to balance both cultures, and establish an understanding of the immigrant and ethnic experience. ii 1 Introduction Julia Alvarez and Junot Díaz are acclaimed authors who have built their narratives around their personal experiences as Dominican-Americans. -

Martina Urioste-Buschmann Literary Representations Of

Martina Urioste-Buschmann Literary Representations of Fear and Anger during the Trujillato: An Approach to the Female Performing of Emotions in the Novels In the Time of the Butterflies and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao Leibniz Universität Hannover, Alemania [email protected] Since the dictatorial era of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina came to an end in 1961, various texts of fictional prose have contributed to the Dominican processing of history in terms of artistic inscriptions into a collective memory. In particular, from the late 1990s, literary representations of the Trujillato have been a firm focus of local Dominican writers. This tendency is apparent in the novels published during this period. Diógenes Valdez’s Retrato de dinosaurios en la Era de Trujillo (1997), Marcio Veloz Maggiolo’s Uña y carne. Memorias de la virilidad (1999) and Ángela Hernández’s Mudanza de los sentidos (2001) are just a few examples of this common focus. However, this literary processing regarding one of the darkest chapters of Dominican history has not been promoted solely by local Dominican authors. At the same time, American- Dominican authors have helped give literary expression to this era of political persecution, terror and censorship, which probably claimed more than 30,000 lives.1 Writing in English, “Dominicanyorks” (Herzog 143) managed to situate their texts within a US-American minority literature that was also received by a mainstream audience (Cocco de Filippis 255). Julia Alvarez 1 It is estimated that approximately 30,000 deaths were caused during the massacres of Haitian guest workers ordered by Trujillo in 1937 (Hilton 83). -

Wheaton Athletes Worldwide

WH E A WHEATON T O N 21 INNOVATORS | COMMUNISM TO CHRIST | JIM HEIMBACH '78 | STUDENT DEBT REAR ADMIRAL R. TIMOTHY ZIEMER '68, P.46 USN (RET.) VOLUME 2015 ISSUE 18 3 // // AUTUMN 2015AUTUMN 21 Innovators in the 21st Century WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE Student Debt: Why It’s Worth It From Communism to Christ KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT WHEATON? TELL US! As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to recruit to the College. You have a unique understanding of Wheaton and can easily identify the type of students who will take full advantage of the Wheaton College experience. We value your opinion and invite you to join us in the recruit- ment process. Please send contact information of potential students you believe will thrive in Wheaton’s rigorous and Christ-centered academic environment. We will take the next step to connect with them and begin the process. 800.222.2419 x0 wheaton.edu/refer VOLUME 18 // ISSUE 3 AUTUMN 2015 featuresWHEATON “ I consider my work a success if I can provide a showcase of God’s creation with my creation.” ➝ Facebook facebook.com/ 21 INNOVATORS: ART: wheatoncollege.il LEADING THE JIM HEIMBACH ’78 WAY / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege COMMENCEMENT: STUDENT DEBT: GOD’S DOUBLE WHY IT’S WORTH IT Instagram AGENT 30 34 instagram.com/ / / wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE THE WHEATON FUND + YOU IT ALL ADDS UP TO A BIG DIFFERENCE households gave to 6,650 the Wheaton Fund 75 households gave $10,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund 635 households made a first-time Wheaton Fund gift 5 households gave $100,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund $814,614.85 given by those who gave less than $1,000 to the Wheaton Fund 58.55% of dollars came from alumni 26.57% of dollars came from parents 14.88% of dollars came from friends Numbers included here represent giving through June 10, 2015 Thank you for all you did to make fiscal year 2015 successful! Make your Wheaton Fund gift today to help get fiscal year 2016 off to a strong start. -

The Sigma Tau Delta Review

The Sigma Tau Delta Review Journal of Critical Writing Sigma Tau Delta International English Honor Society Volume 11, 2014 Editor of Publications: Karlyn Crowley Associate Editors: Rachel Gintner Kacie Grossmeier Anna Miller Production Editor: Rachel Gintner St. Norbert College De Pere, Wisconsin Honor Members of Sigma Tau Delta Chris Abani Katja Esson Erin McGraw Kim Addonizio Mari Evans Marion Montgomery Edward Albee Anne Fadiman Kyoko Mori Julia Alvarez Philip José Farmer Scott Morris Rudolfo A. Anaya Robert Flynn Azar Nafisi Saul Bellow Shelby Foote Howard Nemerov John Berendt H.E. Francis Naomi Shihab Nye Robert Bly Alexandra Fuller Sharon Olds Vance Bourjaily Neil Gaiman Walter J. Ong, S.J. Cleanth Brooks Charles Ghigna Suzan-Lori Parks Gwendolyn Brooks Nikki Giovanni Laurence Perrine Lorene Cary Donald Hall Michael Perry Judith Ortiz Cofer Robert Hass David Rakoff Henri Cole Frank Herbert Henry Regnery Billy Collins Peter Hessler Richard Rodriguez Pat Conroy Andrew Hudgins Kay Ryan Bernard Cooper William Bradford Huie Mark Salzman Judith Crist E. Nelson James Sir Stephen Spender Jim Daniels X.J. Kennedy William Stafford James Dickey Jamaica Kincaid Lucien Stryk Mark Doty Ted Kooser Amy Tan Ellen Douglas Ursula K. Le Guin Sarah Vowell Richard Eberhart Li-Young Lee Eudora Welty Timothy Egan Valerie Martin Jessamyn West Dave Eggers David McCullough Jacqueline Woodson Delta Award Recipients Richard Cloyed Elizabeth Holtze Elva Bell McLin Sue Yost Beth DeMeo Elaine Hughes Isabel Sparks Bob Halli E. Nelson James Kevin Stemmler Copyright © 2014 by Sigma Tau Delta All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Sigma Tau Delta, Inc., the International English Honor Society, William C. -

Dictators: Ethnic American Narrative and the Strongman Genre by David

Dictators: Ethnic American Narrative and the Strongman Genre By David C. Liao B.A., State University of New York, Binghamton 2006 M.A., Brown University Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of English at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2015 © 2015 by David C. Liao This dissertation is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _________ __________________________________________ Deak Nabers, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _________ __________________________________________ Tamar Katz, Reader Date _________ __________________________________________ Olakunle George, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _________ __________________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA David Chang Yi Liao was born on July 20, 1984 in Taipei, Taiwan. The child of a diplomat, he has also lived in Houston, Texas and Long Island, New York, as well as spending numerous holidays with his brothers in California. He graduated magna cum laude from the State University of New York at Binghamton in 2006, earning a B.A. in English, with a concentration in Creative Writing. He began pursuing a Master’s Degree in English at Brown University in September of 2006, and began his doctoral studies with the English Department at Brown in the fall of 2008. In the course of completing his Ph.D., he has taught courses in literature and composition at both Brown and Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank the English Department at Brown University, who accepted me into their ranks on two separate occasions. -

Julia Alvarez

Julia Alvarez: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Alvarez, Julia Title: Julia Alvarez Papers Dates: 1963-2014 (bulk 1983-2011) Extent: 224 document boxes, 7 oversize boxes (osb) (106 linear feet), 3 oversize folders (osf), 252 bound volumes (bv), 20 computer disks Abstract: The papers document all major writings by author and poet Julia Alvarez and include notes, typescripts, periodicals, photographs, background research, publicity materials, and electronic files. Editorial, business, and personal correspondence are also present. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-5311 Language: English, Spanish Access: Open for research Certain restrictions apply to the use of electronic files. Please contact the Ransom Center well in advance of your visit if you are interested in accessing this type of material (email: [email protected]). Access to original computer disks and forensic disk images is restricted. Restrictions on Use: Copying electronic files is not permitted. Staff will make a good faith effort to retrieve electronic files from digital media but in certain cases, due to technological obsolescence or file degradation, data may be inaccessible. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase and Gift, 2013-2014 (13-03-009-P, 14-04-009-G) Processed by: Micah Erwin, 2015 and Grace Hansen, 2016 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Alvarez, Julia Manuscript Collection MS-5311 Biographical Sketch The daughter of native Dominicans, Julia Alvarez was born in New York City in 1950. Within three months of her birth her parents decided to return to their homeland overthrow American-backed dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo. The family was forced to flee the Dominican Republic in 1960 when his involvement in a plot to assassinate the dictator was uncovered. -

Pygmalion Scheduled (Or March 12,13,14

Friday, March 6, 1964 ECHO TAYLOR UNIVERSITY — UPLAND, INDIANA VOL. XLIV —NO. 9 George B. Shaw's "Pygmalion Scheduled (or March 12,13,14 Pygmalion, a full length play by transformation, approved of the 12th 13th and 14th. George Bernard Shaw, will be pre project as a scientific experiment, The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, sented at Taylor on March 12, 13, but did not agree with the inhu is portrayed by Marilyn Domhoff; and 14 at 8:15 in Shreiner Audi man treatment that Higgins gave Professor Higgins is played by torium. out to Eliza. Pickering is as intelli Bob Finch; and Colonel Pickering, Mr. Shaw wrote the play to im gent as Higgins, but he has man Higgin's Phonetician cohort, is press upon the public the impor ners becoming a gentleman, which portrayed by Tom Allen. are quite conspicious in Higgins tance of phoneticians in modern The other members of the cast by their absence. day society. include Cliff Robertson, Marion Pickering observes that Higgins Dodd, Eleanor Hustwick, Margo The plot involves Henry Hig- has brought Eliza up from one Dryer, Darlene Young, Ann Lentz, gins, an English speech teacher, grade of living in the direction of Dale Dickey, Gale Strain, and Bob who attempts to transform a Bob Finch, Eleanor Hustwick, and Tom Allen practice a scene another and in the process has Finton. cockney flower girl, Eliza Doo made her unfit for both lives. for the Trojan Player's production of Pygmalion. little, into an English lady by Tickets for the play may be Higgins thinks of himself as a teaching her to speak cultivated purchased prior to the date of very sufficient man until the hand English.