Reconstructing Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election-Violence-Mo

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF IMMIGRATION REVIEW IMMIGRATION COURT xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx In the Matter of: IN REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS XX YYY xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx DECLARATION OF ZZZZZZ I, ZZZZZ, hereby declare under penalty of perjury that the following statements are true and correct to the best of my knowledge. 1. I do not recall having ever met XX YYY in person. This affidavit is based on my review of Mr. YYY’s Application for Asylum and my knowledge of relevant conditions in Haiti. I am familiar with the broader context of Mr. YYY’s application for asylum, including the history of political violence in Haiti, especially surrounding elections, attacks against journalists and the current security and human rights conditions in Haiti. Radio in Haiti 2. In Haiti, radio is by far the most important media format. Only a small percentage of the population can afford television, and electricity shortages limit the usefulness of the televisions that are in service. An even smaller percentage can afford internet access. Over half the people do not read well, and newspaper circulation is minuscule. There are many radio stations in Haiti, with reception available in almost every corner of the country. Radios are inexpensive to buy and can operate without municipal electricity. 3. Radio’s general importance makes it particularly important for elections. Radio programs, especially call-in shows, are Haiti’s most important forum for discussing candidates and parties. As a result, radio stations become contested ground for political advocacy, especially around elections. Candidates, officials and others involved in politics work hard and spend money to obtain favorable coverage. -

The Election Impasse in Haiti

At a glance April 2016 The election impasse in Haiti The run-off in the 2015 presidential elections in Haiti has been suspended repeatedly, after the opposition contested the first round in October 2015. Just before the end of President Martelly´s mandate on 7 February 2016, an agreement was reached to appoint an interim President and a new Provisional Electoral Council, fixing new elections for 24 April 2016. Although most of the agreement has been respected , the second round was in the end not held on the scheduled date. Background After nearly two centuries of mainly authoritarian rule which culminated in the Duvalier family dictatorship (1957-1986), Haiti is still struggling to consolidate its own democratic institutions. A new Constitution was approved in 1987, amended in 2012, creating the conditions for a democratic government. The first truly free and fair elections were held in 1990, and won by Jean-Bertrand Aristide (Fanmi Lavalas). He was temporarily overthrown by the military in 1991, but thanks to international pressure, completed his term in office three years later. Aristide replaced the army with a civilian police force, and in 1996, when succeeded by René Préval (Inite/Unity Party), power was transferred democratically between two elected Haitian Presidents for the first time. Aristide was re-elected in 2001, but his government collapsed in 2004 and was replaced by an interim government. When new elections took place in 2006, Préval was elected President for a second term, Parliament was re-established, and a short period of democratic progress followed. A food crisis in 2008 generated violent protest, leading to the removal of the Prime Minister, and the situation worsened with the 2010 earthquake. -

Haiti's National Elections

Haiti’s National Elections: Issues and Concerns Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs March 23, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41689 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Haiti’s National Elections: Issues and Concerns Summary In proximity to the United States, and with such a chronically unstable political environment and fragile economy, Haiti has been a constant policy issue for the United States. Congress views the stability of the nation with great concern and commitment to improving conditions there. Both Congress and the international community have invested significant resources in the political, economic, and social development of Haiti, and will be closely monitoring the election process as a prelude to the next steps in Haiti’s development. For the past 25 years, Haiti has been making the transition from a legacy of authoritarian rule to a democratic government. Elections are a part of that process. In the short term, elections have usually been a source of increased political tensions and instability in Haiti. In the long term, elected governments in Haiti have contributed to the gradual strengthening of government capacity and transparency. Haiti is currently approaching the end of its latest election cycle. Like many of the previous elections, the current process has been riddled with political tensions, allegations of irregularities, and violence. The first round of voting for president and the legislature was held on November 28, 2010. That vote was marred by opposition charges of fraud, reports of irregularities, and low voter turnout. When the electoral council’s preliminary results showed that out-going President Rene Préval’s little-known protégé, and governing party candidate, Jude Celestin, had edged out a popular musician for a spot in the runoff elections by less than one percent, three days of violent protests ensued. -

Won't Buy All Books

The Courier Volume 4 Issue 31 Article 1 6-4-1971 The Courier, Volume 4, Issue 31, June 4, 1971 Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First CD nursing Nearly 700 class graduates to graduate The fourth commencement College of DuPage will graduate Berg, college president, was the exercises of College of DuPage will its first class of nurses at next speaker. be Friday evening, June 11, at 7:45 week’s commencement exercises. Mrs. Santucci said she is urging in the college gym. About 650 Twenty eight nurses, one of them the students to work in general Associate degrees and about 50 male, will graduate and after hospitals for wide experience certificates in various technologies taking a state board examination before specializing. will be awarded. qualify as registered nurses. The class that was “pinned” Dr. Rodney Berg, college Mary Ann Santucci, chairman of includes: president, will introduce the stage the nursing program, presented Susan Altorfer, Carol Beechler, party and the speakers of the pins to the class at a meeting May Betty Black, Patricia Crandall, evening. Thomas Biggs, president 16 in the Gymnasium. Dr. Rodney Betty Crim, Donna Dorrough, of the Associated Student Body, Noreen Ehlenburg, Gloria Ellis, will make remarks. Phyllis Foster, Denise Gilman, The main speaker of the evening Diane Hastings, Carol Jenkins, will be Dr. -

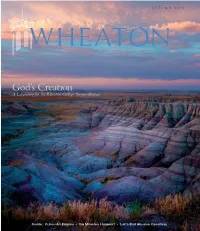

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

Washington N'a Pas Tous Les Torts !

Haïti en Marche, édition du 27 Juillet au 02 Août 2016 • Vol XXX • N° 28 Un président Trump ne serait pas l’ami d’Haïti JACMEL, 23 Juillet – Donald Trump ne saurait être le Cela signifie, a dit Donald Trump, que dans toute décision meilleur ami du peuple haïtien à la Maison blanche. Lors d’une qu’il aura à prendre, s’il est élu président des Etats-Unis, il vérifiera conférence de presse, la veille de recevoir l’investiture du parti d’abord si c’est dans l’intérêt des Etats-Unis. Républicain, le jeudi 21 juillet écoulé, à Cleveland (Ohio), le Et il entend clairement : intérêts économiques. candidat à la présidentielle américaine de novembre prochain, a Aussi voit-on difficilement un tel personnage s’intéresser Donald Trump reçoit l’investiture Républicaine défini dans le détail son slogan ‘America first.’ à la convention du parti tenue à Cleveland (Ohio) (TRUMP / p. 7) Kenneth Merten Washington ‘appui moral’ de Washington n’a pas tous les torts ! JACMEL, 22 Juillet – Entre Haïti et les Etats- Washington manipule, l’Haïtien tantôt il en profite, Unis, chacun tend à accuser l’autre alors qu’il faudrait tantôt il dénonce mais dans les deux cas il n’a rien pu pour aux élections parler plutôt de torts partagés. (WASHINGTON / p. 5) Le président du CEP demanderait aux Etats-Unis de se définir avec plus de clarté P-au-P., 22 juillet 2016 [AlterPresse] --- Le coordonnateur (MERTEN / p. 6) Sén. dominicain Danilo Medina devant Commission Sén. Youri Latortue Le sénateur et homme d’affaires dominicain Danilo Medina comparait devant la commission présidée par le sénateur haïtien Youri Latortue sur l’usage insatisfaisant de fonds (Petrocaribe) dans des projets de construction confiés à des compagnies appartenant au parlementaire dominicain et restés inachevés (photo J.J. -

Country Fact Sheet HAITI June 2007

National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca ● Français ● Home ● Contact Us ● Help ● Search ● canada.gc.ca Home > Research > National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Country Fact Sheet HAITI June 2007 Disclaimer 3. POLITICAL PARTIESF Front for Hope (Front de l’espoir, Fwon Lespwa): The Front for Hope was founded in 2005 to support the candidacy of René Préval in the 2006 presidential election.13 This is a party of alliances that include the Effort and Solidarity to Build a National and Popular Alternative (Effort de solidarité pour la construction d’une alternative nationale et populaire, ESCANP);14 the Open the Gate Party (Pati Louvri Baryè, PLB);15 and grass-roots organizations, such as Grand-Anse Resistance Committee Comité de résistance de Grand-Anse), the Central Plateau Peasants’ Group (Mouvement paysan du plateau Central) and the Southeast Kombit Movement (Mouvement Kombit du SudEst or Kombit Sudest).16 The Front for Hope is headed by René Préval,17 the current head of state, elected in 2006.18 In the 2006 legislative elections, the party won 13 of the 30 seats in the Senate and 24 of the 99 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.19 Merging of Haitian Social Democratic Parties (Parti Fusion des sociaux-démocrates haïtiens, PFSDH): This party was created on 23 April 2005 with the fusion of the following three democratic parties: Ayiti Capable (Ayiti kapab), the National Congress of Democratic Movements (Congrès national des -

Wheaton Athletes Worldwide

WH E A WHEATON T O N 21 INNOVATORS | COMMUNISM TO CHRIST | JIM HEIMBACH '78 | STUDENT DEBT REAR ADMIRAL R. TIMOTHY ZIEMER '68, P.46 USN (RET.) VOLUME 2015 ISSUE 18 3 // // AUTUMN 2015AUTUMN 21 Innovators in the 21st Century WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE Student Debt: Why It’s Worth It From Communism to Christ KNOW A STUDENT WHO BELONGS AT WHEATON? TELL US! As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to recruit to the College. You have a unique understanding of Wheaton and can easily identify the type of students who will take full advantage of the Wheaton College experience. We value your opinion and invite you to join us in the recruit- ment process. Please send contact information of potential students you believe will thrive in Wheaton’s rigorous and Christ-centered academic environment. We will take the next step to connect with them and begin the process. 800.222.2419 x0 wheaton.edu/refer VOLUME 18 // ISSUE 3 AUTUMN 2015 featuresWHEATON “ I consider my work a success if I can provide a showcase of God’s creation with my creation.” ➝ Facebook facebook.com/ 21 INNOVATORS: ART: wheatoncollege.il LEADING THE JIM HEIMBACH ’78 WAY / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege COMMENCEMENT: STUDENT DEBT: GOD’S DOUBLE WHY IT’S WORTH IT Instagram AGENT 30 34 instagram.com/ / / wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE THE WHEATON FUND + YOU IT ALL ADDS UP TO A BIG DIFFERENCE households gave to 6,650 the Wheaton Fund 75 households gave $10,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund 635 households made a first-time Wheaton Fund gift 5 households gave $100,000 or more to the Wheaton Fund $814,614.85 given by those who gave less than $1,000 to the Wheaton Fund 58.55% of dollars came from alumni 26.57% of dollars came from parents 14.88% of dollars came from friends Numbers included here represent giving through June 10, 2015 Thank you for all you did to make fiscal year 2015 successful! Make your Wheaton Fund gift today to help get fiscal year 2016 off to a strong start. -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

Haiti's National Elections

Haiti’s National Elections: Issues, Concerns, and Outcome Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs July 18, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41689 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Haiti’s National Elections: Issues, Concerns, and Outcome Summary In proximity to the United States, and with such a chronically unstable political environment and fragile economy, Haiti has been a constant policy issue for the United States. Congress views the stability of the nation with great concern and commitment to improving conditions there. The Obama Administration considers Haiti its top priority in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Both Congress and the international community have invested significant resources in the political, economic, and social development of Haiti, and have closely monitored the election process as a prelude to the next steps in Haiti’s development. For the past 25 years, Haiti has been making the transition from a legacy of authoritarian rule to a democratic government. Elections are a part of that process. In the short term, elections have usually been a source of increased political tensions and instability in Haiti. In the long term, elected governments in Haiti have contributed to the gradual strengthening of government capacity and transparency. Haiti has concluded its latest election cycle, although it is still finalizing the results of a few legislative seats. The United States provided $16 million in election support through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Like many of the previous Haitian elections, the recent process has been riddled with political tensions, violence, allegations of irregularities, and low voter turnout. -

Pygmalion Scheduled (Or March 12,13,14

Friday, March 6, 1964 ECHO TAYLOR UNIVERSITY — UPLAND, INDIANA VOL. XLIV —NO. 9 George B. Shaw's "Pygmalion Scheduled (or March 12,13,14 Pygmalion, a full length play by transformation, approved of the 12th 13th and 14th. George Bernard Shaw, will be pre project as a scientific experiment, The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, sented at Taylor on March 12, 13, but did not agree with the inhu is portrayed by Marilyn Domhoff; and 14 at 8:15 in Shreiner Audi man treatment that Higgins gave Professor Higgins is played by torium. out to Eliza. Pickering is as intelli Bob Finch; and Colonel Pickering, Mr. Shaw wrote the play to im gent as Higgins, but he has man Higgin's Phonetician cohort, is press upon the public the impor ners becoming a gentleman, which portrayed by Tom Allen. are quite conspicious in Higgins tance of phoneticians in modern The other members of the cast by their absence. day society. include Cliff Robertson, Marion Pickering observes that Higgins Dodd, Eleanor Hustwick, Margo The plot involves Henry Hig- has brought Eliza up from one Dryer, Darlene Young, Ann Lentz, gins, an English speech teacher, grade of living in the direction of Dale Dickey, Gale Strain, and Bob who attempts to transform a Bob Finch, Eleanor Hustwick, and Tom Allen practice a scene another and in the process has Finton. cockney flower girl, Eliza Doo made her unfit for both lives. for the Trojan Player's production of Pygmalion. little, into an English lady by Tickets for the play may be Higgins thinks of himself as a teaching her to speak cultivated purchased prior to the date of very sufficient man until the hand English. -

Election-Report-11-2

Haiti’s November 28 Elections: Trying to Legitimize the Illegitimate November 22, 2010 Introduction Voices from across the political spectrum in both Haiti and the U.S., joined by human rights groups, and most importantly, Haitian voters—have warned both the Haitian and U.S. governments that the deeply flawed elections in Haiti currently scheduled for November 28 risk putting the country into turmoil and endangering all investment in reconstruction. But the U.S. and Haitian Administrations refuse to listen. The November elections may be the most important in Haitian history. Voters will choose the entire House of Deputies for four years, a President for five years, and one- third of the Senate for six years. These officials will have the responsibility of guiding Haiti’s reconstruction for at least the next four years, which will require making many hard, important decisions that will shape Haitian society for decades. Since our June report calling for fair elections, The International Community Should Pressure the Haitian Government for Prompt and Fair Elections, widespread election irregularities continue to threaten to send the nation into a political crisis. As it stands, the elections planned for November 28 are neither fair nor credible. The United States and other international donors have committed to funding and working with the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP), ignoring allegations of fraud, unconstitutional activity, and the politically motivated exclusion of candidates and entire political parties. On October 7, 2010, U.S. Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-CA) and 44 other Members of Congress sent a letter urging Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton to support free, fair and open elections in Haiti.1 The letter warned that supporting flawed elections ‚will come back to haunt the international community‛ by generating unrest and threatening the implementation of earthquake reconstruction projects.