The Play of Morality in Feng Xiaogang's Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

A World Without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies

A World without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies Rujie Wang, College of Wooster Should we get serious about A World without Thieves (tian xia wu zei), with two highly skilled pickpockets, Wang Bo (played by Liu Dehua) and Wang Li (Liu Ruoying), risking their lives to protect both the innocence and the hard-earned money of an orphan and idiot who does not believe there are thieves in the world? The answer is yes, not because this film is a success in the popular entertainment industry but in spite of it. To Feng Xiaogang’s credit, the film allows the viewer to feel the pulse of contemporary Chinese cultural life and to express a deep anxiety about modernization. In other words, this production by Feng Xiaogang to ring in the year of the roster merits our critical attention because of its function as art to compensate for the harsh reality of a capitalist market economy driven by money, profit, greed, and individual entrepreneurial spirit, things of little value in the old ethical and religious traditions. The title is almost sinisterly ironic, considering the national problem of corruption and crime that often threatens to derail economic reform in China, although it may ring true for those optimists clinging tenaciously to the old moral ideals, from Confucians to communists, who have always cherished the utopia of a world without thieves. Even during the communist revolutions that redistributed wealth and property by violence and coercion, that utopian fantasy was never out of favor or discouraged; during the Cultural Revolution, people invented and bought whole-heartedly into the myth of Lei Feng (directed by Dong Yaoqi, 1963), a selfless PLA soldier and a paragon of socialist virtues, who wears socks with holes but manages to donate all his savings to the flood victims in a people’s commune. -

0Ca60ed30ebe5571e9c604b661

Mark Parascandola ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI Cofounders: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff Creative Director: Ursula Damm Copy Editors: Nancy Hubbard, Barbara Richard © 2019 Daylight Community Arts Foundation Photographs and text © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Notes on the Locations © 2019 by Mark Parascandola Once Upon a Time in Shanghai: Images of a Film Industry in Transition © 2019 by Michael Berry All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-942084-74-7 Printed by OFSET YAPIMEVI, Istanbul No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher. Daylight Books E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.daylightbooks.org 4 5 ONCE UPON A TIME IN SHANGHAI: IMAGES OF A FILM INDUSTRY IN TRANSITION Michael Berry THE SOCIALIST PERIOD Once upon a time, the Chinese film industry was a state-run affair. From the late centers, even more screenings took place in auditoriums of various “work units,” 1940s well into the 1980s, Chinese cinema represented the epitome of “national as well as open air screenings in many rural areas. Admission was often free and cinema.” Films were produced by one of a handful of state-owned film studios— tickets were distributed to employees of various hospitals, factories, schools, and Changchun Film Studio, Beijing Film Studio, Shanghai Film Studio, Xi’an Film other work units. While these films were an important part of popular culture Studio, etc.—and the resulting films were dubbed in pitch-perfect Mandarin during the height of the socialist period, film was also a powerful tool for education Chinese, shot entirely on location in China by a local cast and crew, and produced and propaganda—in fact, one could argue that from 1949 (the founding of the almost exclusively for mainland Chinese film audiences. -

Charles Zhang

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema. -

Middlebrow Cinema

7 WEALTH AND JUSTICE Contemporary Chinese middlebrow cinema Ting Guo Introduction In the past decade, the theme of the middle class in Chinese cinema has attracted considerable attention from critics and scholars in China, focusing on the middle class either as the dominant narrative of contemporary Chinese films or as the main audiences of Chinese cinema (see Duan 2007; Yang 2011; Zhang 2011). However, despite this increasing interest in this newly emergent middle-class culture in Chinese cinema, the term ‘middlebrow’ (中眉 zhongmei or 平眉 pingmei in Chinese)1 has been seldom discussed or used. I will argue that the caution that Chinese film scholars have shown in applying the con- cept of middlebrow to the Chinese context is partly related to the porosity between the concepts of middlebrow culture and middle-class culture, and partly related to the ambivalent position that the new middle-class taste has in current Chinese cinematic culture, as this taste has itself been fostered in part by the state. However, before we think middlebrow across borders, it is important to revisit the use of the term in its original context. Since its origin in Britain and Ireland, ‘middlebrow’ has been persistently identified by literary critics, from F.R. Leavis and Q.D. Leavis (1932) to Virginia Woolf (1942) and Dwight MacDonald (1960), as a pejorative label for intellectually inferior cultural production that vulgarizes and devalues high culture. Since the 1990s, this early hostility on the part of literary critics has been identified as an expression of contemporary anxieties about cultural authority and fear of cultural change (see Baxendale and Pawling 1996; Rubin 2002; Brown and Grover 2012). -

From China with a Laugh: a Perusal of Chinese Comedy Films

From China with a Laugh: A Perusal of Chinese Comedy Films Shaoyi Sun Laughter has always been a rarity in Chinese official culture. The dead serious Confucians were too engaged with state affairs and everyday mannerism to enjoy a laugh. Contemporary Party officials are oftentimes too self-important to realize they could easily become a target of ridicule. Some thirty years ago, the legendary Chinese literary critic C. T. Hsia (1921-) observed that, despite the fact that modern Chinese life “constitutes a source of ‘unconscious’ humor to a good-tempered onlooker, foreign or Chinese”; and despite the allegation that “China is a rich land of humor, not because the people have adopted the humorous attitude but rather because they can be objects of humorous contemplation,” modern Chinese writers, however, “stopped at the sketch or essay and did not create a sustained humorous vision of modern Chinese life.”1 Having said that, Chinese laughter/humor is by no means in short supply. While a Taoist hedonist may find joy and laughter in the passing of his beloved wife, a modern-day cross talker (typically delivered in the Beijing dialect, crosstalk or xiangsheng is a traditional comedic performance of China that usually involves two talkers in a rapid dialogue, rich in social and political satire) has no problem in finding a willing ear and a knowing laugh when he cracks a joke at the government official, the pot-bellied businessman, or the self-proclaimed public intellectual. Laughter and humor, therefore, triumph in popular imagination, unorthodox writings, folk literature, and other mass entertainment forms. -

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times Edited by Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey A Companion Volume to H umour in Chinese Life and Letters: Classical and Traditional Approaches Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2013 ISBN 978-988-8139-23-1 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8139-24-8 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Limited, Hong Kong, China Contents List of illustrations and tables vii Contributors xi Editors’ note xix Preface xxi 1. Humour and its cultural context: Introduction and overview 1 Jessica Milner Davis 2. The phantom of the clock: Laughter and the time of life in the 23 writings of Qian Zhongshu and his contemporaries Diran John Sohigian 3. Unwarranted attention: The image of Japan in twentieth-century 47 Chinese humour Barak Kushner 4 Chinese cartoons and humour: The views of fi rst- and second- 81 generation cartoonists John A. Lent and Xu Ying 5. “Love you to the bone” and other songs: Humour and rusheng 103 rhymes in early Cantopop Marjorie K. M. Chan and Jocelyn Chey 6. -

Mise En Page 1

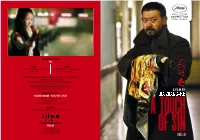

INTERNATIONAL SALES MK2 PARIS CANNES MK2 - 55 rue Traversière FIVE HOTEL - 1 rue Notre-Dame 75012 Paris 06400 Cannes Juliette Schrameck, Head of International Sales & Acquisitions [email protected] Fionnuala Jamison, International Sales Executive [email protected] Victoire Thevenin, International Sales Executive [email protected] A FILM BY INTERNATIONAL PRESS RICHARD LORMAND - FILM ⎮PRESS ⎮PLUS JIA ZHANG-KE www.FilmPressPlus.com [email protected] Tel: +33-9-7044-9865 / +33-6-2424-1654 m IN CANNES o c . s Tel: 08 70 44 98 65 / 06 09 92 55 47 / 06 24 24 16 54 a e r c - l e s k a . w w w : k r o w t XSTREAM PICTURES (BEIJING) r EVA LAM A Tel: +86 10 8235 0984 Fax: +86 10 8235 4938 [email protected] Xstream Pictures (Beijing), Office Kitano Shangai Film Group Corporation & MK2 present A FILM BY JIA ZHANG-KE 133 min / Color / 1:2.4 / 2013 Xstream Pictures (Beijing ) Office Kitano Shanghai Film Group Corporation Present In association with Shanxi Film and Television Group Bandai Visual Bitters End SYNOPSIS DIRECTOR’S NOTE This film is about four deaths, four incidents which actually happened in China in recent years: three murders and one suicide. These incidents are well-known to people throughout China. They happened in Shanxi, Chongqing, Hubei and Guangdong – that is, from the north to the south, spanning much of the country. I wanted to use these news reports to build a comprehensive portrait of life in contemporary China. China is still changing rapidly, in a way that makes the country look more prosperous than before. -

Genre Film, Media Corporations, and The

This article was downloaded by: [Simon Fraser University] On: 20 December 2011, At: 21:18 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Asian Studies Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/casr20 Genre Film, Media Corporations, and the Commercialisation of the Chinese Film Industry: The Case of “New Year Comedies” Shuyu Kong a a University of Sydney Available online: 04 Apr 2008 To cite this article: Shuyu Kong (2007): Genre Film, Media Corporations, and the Commercialisation of the Chinese Film Industry: The Case of “New Year Comedies” , Asian Studies Review, 31:3, 227-242 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10357820701559055 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Master Document Template

Copyright by Yi Lu 2009 The Thesis Committee for Yi Lu Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Feng Xiaogang, New Year Films, and the Transformation of Chinese Film Industry In the 1990s APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Sung-seng Yvonne Chang Tom Schatz Feng Xiaogang, New Year Films, and the Transformation of Chinese Film Industry In the 1990s by Yi Lu, B.A., M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2009 Dedication To My Parents . Acknowledgements I would first like to express my deep gratitude to Prof. Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang for her insights, open-mindedness, boundless support, and constant encouragement, which have been instrumental in my graduate research study. Next, I am sincerely grateful to Prof. Tom Schatz for his intellectual curiosity, wisdom, and extremely practical input about the future development of this project. Prof. Chang and Prof. Schatz‘s belief in my value as a scholar has given me the confidence to believe in my ideas. Their constructive criticism and advice have been extremely helpful. I would also like to extend thanks to the lecturers and staff of the Department of Asian Studies, who were very encouraging and helpful to me during this process. I also wish to thank the faculty in the Department of Radio, Television, and Film for their wonderful courses and guidance. They provided invaluable support for this research. -

Film and Society in China the Logic of the Market

11 Film and Society in China The Logic of the Market Stanley Rosen By 2011, after more than thirty years of reform in China, developments in the film industry reminded observers how far the industry has come, pointed to future directions and still evolving trends, and suggested some of the key issues that are likely to remain contentious for the foreseeable future. Since these developments are closely linked to the interactive role between Chinese film and society, it is useful at the outset to note some of the major recent developments suggested above. First, 2010 continued the familiar annual increase in box-office performance that has been a feature of the Chinese market over the last decade. By 2008 China’s box-office revenues had hit RMB 4.3 billion, bringing the country for the first time into the top ten film markets in the world. After climbing to RMB 6.1 billion in 2009, the figure for 2010 reached a remarkable RMB 10.17 billion, a 43 percent increase over the previous year; as recently as 2003 the box-office total had been under RMB 1 billion (H. Liu 2011).1 While previously lacking an “industry” in any commonly understood sense of that term, Chinese film authorities and filmmak- ers are now driven more and more by the bottom line, dedicated to making films that will bring audiences into the theaters. The increasing importance of the box office and the implications for the Chinese film industry and Chinese society are a major theme of this chapter. Second and very much related to the first point, the familiar boundaries – and contradictions – among art, politics, and commerce (Zhu and Rosen 2010) have begun to break down, with films previously designated as “main melody” in China and “propaganda” films abroad successfully finding ways to stimulate audience interest.