Middlebrow Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

Harmonious Cooperation, Essential for Myanmar Arts to Become

Established 1914 Volume XVIII, Number 245 1st Waning of Nadaw 1372 ME Wednesday, 22 December, 2010 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round develop- * Uplift of the morale and morality of the entire * Stability of the State, community peace and ment of other sectors of the economy as well nation tranquillity, prevalence of law and order * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic system * Uplift of national prestige and integrity and * National reconsolidation * Development of the economy inviting participation in terms of preservation and safeguarding of cultural her- * Emergence of a new enduring State Constitu- technical know-how and investments from sources inside the itage and national character tion country and abroad * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit * Building of a new modern developed nation in * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept in the * Uplift of health, fitness and education stand- accord with the new State Constitution hands of the State and the national peoples ards of the entire nation Harmonious cooperation, essential for Myanmar arts to become popular worldwide Information Minister attends presenting of cash donations for 2nd ceremony to pay respects to old musicians YANGON, 21 Dec— music world and the music Myanmar music to become The presenting of cash do- community. Music popular worldwide as well Minister nations to organize the professionals not only as the need of preserving second ceremony to pay serve national interests and promoting tradition for Infor- respects to octogenarian hand in hand with the gov- and national culture. -

A World Without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies

A World without Thieves: Film Magic and Utopian Fantasies Rujie Wang, College of Wooster Should we get serious about A World without Thieves (tian xia wu zei), with two highly skilled pickpockets, Wang Bo (played by Liu Dehua) and Wang Li (Liu Ruoying), risking their lives to protect both the innocence and the hard-earned money of an orphan and idiot who does not believe there are thieves in the world? The answer is yes, not because this film is a success in the popular entertainment industry but in spite of it. To Feng Xiaogang’s credit, the film allows the viewer to feel the pulse of contemporary Chinese cultural life and to express a deep anxiety about modernization. In other words, this production by Feng Xiaogang to ring in the year of the roster merits our critical attention because of its function as art to compensate for the harsh reality of a capitalist market economy driven by money, profit, greed, and individual entrepreneurial spirit, things of little value in the old ethical and religious traditions. The title is almost sinisterly ironic, considering the national problem of corruption and crime that often threatens to derail economic reform in China, although it may ring true for those optimists clinging tenaciously to the old moral ideals, from Confucians to communists, who have always cherished the utopia of a world without thieves. Even during the communist revolutions that redistributed wealth and property by violence and coercion, that utopian fantasy was never out of favor or discouraged; during the Cultural Revolution, people invented and bought whole-heartedly into the myth of Lei Feng (directed by Dong Yaoqi, 1963), a selfless PLA soldier and a paragon of socialist virtues, who wears socks with holes but manages to donate all his savings to the flood victims in a people’s commune. -

List of Action Films of the 2010S - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of action films of the 2010s - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_action_films_of_the_2010s List of action films of the 2010s From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is an incomplete list, which may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness. You can help by expanding it (//en.wikipedia.org /w/index.php?title=List_of_action_films_of_the_2010s&action=edit) with reliably sourced entries. This is chronological list of action films originally released in the 2010s. Often there may be considerable overlap particularly between action and other genres (including, horror, comedy, and science fiction films); the list should attempt to document films which are more closely related to action, even if it bends genres. Title Director Cast Country Sub-Genre/Notes 2010 13 Assassins Takashi Miike Koji Yakusho, Takayuki Yamada, Yusuke Iseya Martial Arts[1] 14 Blades Daniel Lee Donnie Yen, Vicky Zhao, Wu Chun Martial Arts[2] The A-Team Joe Carnahan Liam Neeson, Bradley Cooper, Quinton Jackson [3] Alien vs Ninja Seiji Chiba Masanori Mimoto, Mika Hijii, Shuji Kashiwabara [4][5] Bad Blood Dennis Law Simon Yam, Bernice Liu, Andy On [6] Sorapong Chatree, Supaksorn Chaimongkol, Kiattisak Bangkok Knockout Panna Rittikrai, Morakot Kaewthanee [7] Udomnak Blades of Blood Lee Joon-ik Cha Seung-won, Hwang Jung-min, Baek Sung-hyun [8] The Book of Eli Albert Hughes, Allen Hughes Denzel Washington, Gary Oldman, Mila Kunis [9] The Bounty Hunter Andy Tennant Jennifer Aniston, Gerard Butler, Giovanni Perez Action comedy[10] The Butcher, the Chef and the Wuershan Masanobu Ando, Kitty Zhang, You Benchang [11] Swordsman Centurion Neil Marshall Michael Fassbender, Olga Kurylenko, Dominic West [12] City Under Siege Benny Chan [13] The Crazies Breck Eisner Timothy Olyphant, Radha Mitchell, Danielle Panabaker Action thriller[14] Date Night Shawn Levy Steve Carell, Tina Fey, Mark Wahlberg Action comedy[15] The Expendables Sylvester Stallone Sylvester Stallone, Jason Statham, Jet Li [16] Faster George Tillman, Jr. -

Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China Since 1990

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 43 Literary Production and Popular Culture Film Adaptations in China since 1990 Yimiao ZHU Nanjing Normal University, China Email: [email protected] Abstract: Since their invention, films have developed hand-in-hand with literature and film adaptations of literature have constituted the most important means of exchange between the two mediums. Since 1990, Chinese society has been undergoing a period of complete political, economic and cultural transformation. Chinese literature and art have, similarly, experienced unavoidable changes. The market economy has brought with it popular culture and stipulated a popularisation trend in film adaptations. The pursuit of entertainment and the expression of people’s anxiety have become two important dimensions of this trend. Meanwhile, the tendency towards popularisation in film adaptations has become a hidden factor influencing the characteristic features of literature and art. While “visualization narration” has promoted innovation in literary style, it has also, at the same time, damaged it. Throughout this period, the interplay between film adaptation and literary works has had a significant guiding influence on their respective development. Key Words: Since 1990; Popular culture; Film adaptation; Literary works; Interplay Volume 12, No. 1 44 Since its invention, cinema has used “adaptation” to cooperate closely with literature, draw on the rich, accumulated literary tradition and make up for its own artistic deficiencies during early development. As films became increasingly dependent on their connection with the novel, and as this connection deepened, accelerating the maturity of cinematic art, by the time cinema had the strength to assert its independence from literature, the vibrant phase of booming popular culture and rampant consumerism had already begun. -

Academy Invites 774 to Membership

MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] June 28, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ACADEMY INVITES 774 TO MEMBERSHIP LOS ANGELES, CA – The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is extending invitations to join the organization to 774 artists and executives who have distinguished themselves by their contributions to theatrical motion pictures. Those who accept the invitations will be the only additions to the Academy’s membership in 2017. 30 individuals (noted by an asterisk) have been invited to join the Academy by multiple branches. These individuals must select one branch upon accepting membership. New members will be welcomed into the Academy at invitation-only receptions in the fall. The 2017 invitees are: Actors Riz Ahmed – “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” “Nightcrawler” Debbie Allen – “Fame,” “Ragtime” Elena Anaya – “Wonder Woman,” “The Skin I Live In” Aishwarya Rai Bachchan – “Jodhaa Akbar,” “Devdas” Amitabh Bachchan – “The Great Gatsby,” “Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham…” Monica Bellucci – “Spectre,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” Gil Birmingham – “Hell or High Water,” “Twilight” series Nazanin Boniadi – “Ben-Hur,” “Iron Man” Daniel Brühl – “The Zookeeper’s Wife,” “Inglourious Basterds” Maggie Cheung – “Hero,” “In the Mood for Love” John Cho – “Star Trek” series, “Harold & Kumar” series Priyanka Chopra – “Baywatch,” “Barfi!” Matt Craven – “X-Men: First Class,” “A Few Good Men” Terry Crews – “The Expendables” series, “Draft Day” Warwick Davis – “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” “Harry Potter” series Colman Domingo – “The Birth of a Nation,” “Selma” Adam -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema. -

Chinese Transnational Cinema and the Collaborative Tilt Toward South Korea Brian Yecies University of Wollongong, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2016 Chinese transnational cinema and the collaborative tilt toward South Korea Brian Yecies University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Yecies, B. "Chinese transnational cinema and the collaborative tilt toward South Korea." The aH ndbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in China. Ed.M. Keane. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar, 2016, 226-244. 2016 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Chinese transnational cinema and the collaborative tilt toward South Korea Abstract To shed light on the important and growing trend in international filmmaking, this chapter investigates the increasing levels of co-operation in co-productions and post-production work between China and Korea since the mid-2000s, following a surge in personnel exchange and technological transfer. It explains how a range of international relationships and industry connections is contributing to a new ecology of expertise, which in turn is boosting the expansion of China’s domestic market and synergistically transforming the shape and style of Chinese cinema. Keywords transnational, cinema, collaborative, tilt, toward, south, korea, chinese Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Yecies, B. "Chinese transnational cinema and the collaborative tilt toward South Korea." The aH ndbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in China. Ed.M. Keane. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar, 2016, 226-244. -

Liu, Xiao. "From the Glaring Sun to Flying Bullets: Aesthetics And

Liu, Xiao. "From the Glaring Sun to Flying Bullets: Aesthetics and Memory in the ‘Post-’ Era Chinese Cinema." China’s iGeneration: Cinema and Moving Image Culture for the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu and Luke Vulpiani. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 321–336. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501300103.ch-017>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 13:31 UTC. Copyright © Matthew D. Johnson, Keith B. Wagner, Tianqi Yu, Luke Vulpiani and Contributors 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 17 From the Glaring Sun to Flying Bullets: Aesthetics and Memory in the ‘Post-’ Era Chinese Cinema Xiao Liu How do we remember the past in a post-medium era in which our memories of a previous era are increasingly reliant upon, and thus continually revised by, the ubiquitous presence of media networks? Writing about the weakening historicity under late capitalism, Fredric Jameson sharply points out that the past has been reduced to ‘a multitudinous photographic simulacrum,’ ‘a set of dusty spectacles.’1 Following Guy Debord’s critique of the spectacle as ‘the final form of commodity reification’ in a society ‘where exchange value has been generalized to the point at which the very memory of use value is effaced,’ Jameson reveals the ways in which the past appropriated by what he calls ‘nostalgia films’ is ‘now refracted through the iron law of fashion change and the emergent ideology of the generation’ for omnivorous consumption that is an outcome of neoliberalism and its cultural motor – post- modernism. -

Mise En Page 1

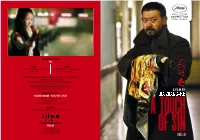

INTERNATIONAL SALES MK2 PARIS CANNES MK2 - 55 rue Traversière FIVE HOTEL - 1 rue Notre-Dame 75012 Paris 06400 Cannes Juliette Schrameck, Head of International Sales & Acquisitions [email protected] Fionnuala Jamison, International Sales Executive [email protected] Victoire Thevenin, International Sales Executive [email protected] A FILM BY INTERNATIONAL PRESS RICHARD LORMAND - FILM ⎮PRESS ⎮PLUS JIA ZHANG-KE www.FilmPressPlus.com [email protected] Tel: +33-9-7044-9865 / +33-6-2424-1654 m IN CANNES o c . s Tel: 08 70 44 98 65 / 06 09 92 55 47 / 06 24 24 16 54 a e r c - l e s k a . w w w : k r o w t XSTREAM PICTURES (BEIJING) r EVA LAM A Tel: +86 10 8235 0984 Fax: +86 10 8235 4938 [email protected] Xstream Pictures (Beijing), Office Kitano Shangai Film Group Corporation & MK2 present A FILM BY JIA ZHANG-KE 133 min / Color / 1:2.4 / 2013 Xstream Pictures (Beijing ) Office Kitano Shanghai Film Group Corporation Present In association with Shanxi Film and Television Group Bandai Visual Bitters End SYNOPSIS DIRECTOR’S NOTE This film is about four deaths, four incidents which actually happened in China in recent years: three murders and one suicide. These incidents are well-known to people throughout China. They happened in Shanxi, Chongqing, Hubei and Guangdong – that is, from the north to the south, spanning much of the country. I wanted to use these news reports to build a comprehensive portrait of life in contemporary China. China is still changing rapidly, in a way that makes the country look more prosperous than before. -

Genre Film, Media Corporations, and The

This article was downloaded by: [Simon Fraser University] On: 20 December 2011, At: 21:18 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Asian Studies Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/casr20 Genre Film, Media Corporations, and the Commercialisation of the Chinese Film Industry: The Case of “New Year Comedies” Shuyu Kong a a University of Sydney Available online: 04 Apr 2008 To cite this article: Shuyu Kong (2007): Genre Film, Media Corporations, and the Commercialisation of the Chinese Film Industry: The Case of “New Year Comedies” , Asian Studies Review, 31:3, 227-242 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10357820701559055 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.