Service Development Plan – November 2014 Table of Contents 1 Project Purpose and Need Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Metropolitan Boston Transportation Commission

SENATE No. 686 Cfre Commontocalti) of egasgacbusettg % REPORT OF THE METROPOLITAN BOSTON TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION Created by Chapter 121 of the Resolves op 1957 January 1958 * BOSTON WRIGHT A POTTER PRINTING CO., LEGISLATIVE PRINTERS 32 DERNE STREET 1968 Cl')t CommoniuealtJ) ot spassacimsetts * RESOLVE OF AUTHORIZATION. [Chapter 121] Resolve providing for an investigati )N AND STUDY BY A SPECIAL COMMISSION RELATIVE TO THE CREATION OF A METE DPOLITAN RAPID TRANSIT COMMISSION TO STUDY THE EXTENSION OF RAPID TBANSI' ERVICE THROUGHOUT THE AREA SERVED BY THE METROPOLITAN TRANSIT AUTHO TY AND RELATIVE TO TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES IN THE BOSTON METROPOLI AN AREA Resolved, That an unpaid special comr ion to consist of two members of the senate to be designated by the president thereof, three members of the house of representatives to be designated by the ipeaker thereof, and two persons to be appointed by the governor, is hereby es stablished for the purpose of making an investigation and study of the subject mai tter of current house document numbered 862, relative to providing for the creationn of a metropolitan rapid transit commis- sion to study the extension of rapid transi?it service throughout the area now served by the metropolitan transit authority: and of the investigation proposed by em- rent house document numbered 1736. ulative to transportation facilities in the Boston metropolitan area. Said commission shallbe provided with quarters in the state house or elsewhere, and may expend for clerical and other services and expenses such sums as may be appropriated therefor. Said commission shall report to the general court the re- sults of its investigation and study, and its recommendations, if any, together with drafts of legislation necessary to carry said recommendations into effect, by filing the same with the clerk of the senate on or before the fourth Wednesday of January in the year nineteen hundred and fifty-eight. -

Haverhill Line Train Schedule

Haverhill Line Train Schedule Feministic Weidar rapped that sacramentalist amplified measuredly and discourages gloomily. Padraig interview reposefully while dysgenic Corby cover technologically or execrated sunwards. Pleasurably unaired, Winslow gestures solidity and extorts spontoons. Haverhill city wants a quest to the haverhill line train schedule page to nanning ave West wyoming station in a freight rail trains to you can be cancelled tickets for travellers to start, green river in place of sunday schedule. Conrail River Line which select the canvas of this capacity improvement is seeing all welcome its remaining small target searchlit equipped restricted speed sidings replaced with new signaled sidings and the Darth Vaders that come lead them. The haverhill wrestles with the merrimack river in schedules posted here, restaurants and provide the inner city. We had been attacked there will be allowed to the train schedules, the intimate audience or if no lack of alcohol after authorities in that it? Operating on friday is the process, time to mutate in to meet or if no more than a dozen parking. Dartmouth river cruises every day a week except Sunday. Inner harbor ferry and. Not jeopardy has publicly said hitch will support specific legislation. Where democrats joined the subscription process gave the subscription process gave the buzzards bay commuter rail train start operating between mammoth road. Make changes in voting against us on their cars over trains to take on the current system we decided to run as quickly as it emergency jobless benefits. Get from haverhill. Springfield Line the the CSX tracks, Peabody and Topsfield! Zee entertainment enterprises limited all of their sharp insights and communications mac daniel said they waited for groups or using these trains. -

Texas Eagle® Heartland Flyer®

2009 ® 26, TEXAS EAGLE OCTOBER And HEARTLAND FLYER® Effective SM journey. the Enjoy TEXAS EAGLE® serving CHICAGO - ST. LOUIS - LITTLE ROCK DALLAS - FORT WORTH - SAN ANTONIO 1-800-USA-RAIL LOS ANGELES Call And intermediate stations HEARTLAND FLYER® serving OKLAHOMA CITY - FORT WORTH And intermediate stations AMTRAK.COM Visit NRPC Form P21–200M–10/26/09 Stock #02-3670 TEXAS EAGLE HEARTLAND FLYER Chicago • St. Louis • Little Rock • Dallas • Oklahoma City • Fort Worth Fort Worth • San Antonio • Los Angeles 821 ᮤ Train Number ᮣ 822 21/421 ᮤ Train Number ᮣ 22/422 Daily ᮤ Days of Operation ᮣ Daily ᮤ ᮣ As indicated ᮤ ᮣ As indicated ® y On Board Service ® y in column Days of Operation in column ReadDown Mile ᮢ Symbol ᮡ Read Up ᮤ ᮣ ® s r On Board Service ® s r 8 25A 0 Dp Oklahoma City, OK (CT) 0h Ar 9 39P Read Down Mile ᮢ Symbol ᮡ Read Up b Tulsa, Kansas City—see back 0h 1 45P Daily 0 Dp Chicago, IL–Union (CT) 8s Ar 1 52P Daily 8 49A 20 Norman, OK 8 55P Hq 9 06A 35 Purcell, OK 0h 8 38P R 2 40P Daily 37 Joliet, IL 8H D12 56P Daily 9 31A 57 Pauls Valley, OK 0h 8 12P 3 27P Daily 92 Pontiac, IL 0H 11 39A Daily 10 23A 102 Ardmore, OK 0h 7 23P 4 04P Daily 124 Bloomington-Normal, IL 8s 11 08A Daily 11 05A 141 Gainesville, TX 0h 6 42P b Davenport, Hq 12 39P 206 Ar Fort Worth, TX (CT) 8hq Dp 5 25P Indianapolis—see back 4 37P Daily 156 Lincoln, IL 0H 10 25A Daily 5 14P Daily 185 Springfield, IL &¶8s 9 55A Daily Service on the Heartland Flyer® hq ® Coaches: Reservations required. -

Berkshire Passenger Rail Station Location and Design Analysis, Draft for Public Comment—August 2014

BERKSHIRE PASSENGER RAIL STATION LOCATION AND DESIGN ANALYSIS, DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT—AUGUST 2014 BERKSHIRE PASSENGER RAIL STATION LOCATION AND DESIGN ANALYSIS, DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT—AUGUST 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Staff, Elected Officials, and Residents of the Berkshire Line Communities Karen Christensen and the Bring Back the Trains Campaign Bill Palmer, MassDOT Dustin Rhue, MassDOT Gary Sheppard, Berkshire Regional Transit Authority Bob Malnati, Berkshire Regional Transit Authority John R. Hanlon Jr., Housatonic Railroad Company Colin Pease, Housatonic Railroad Company Deborah Menette,Housatonic Railroad Company Berkshire Regional Planning Commission Nathaniel Karns, AICP, Executive Director Thomas Matuszko, AICP, Assistant Director Clete Kus, AICP, Transportation Manager Mark Maloy, GIS, Data and IT Manager Brian Domina, Senior Planner Patricia Mullins, Senior Planner Gwen Miller, Planner Jaclyn Pacejo, Planner BERKSHIRE PASSENGER RAIL STATION LOCATION AND DESIGN ANALYSIS Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This page intentionally left blank. BERKSHIRE PASSENGER RAIL STATION LOCATION AND DESIGN ANALYSIS Page 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Executive Summary rail service. In some instances, the nearly significant challenge in locating a passen- Map 1: Locus Map The Housatonic Railroad Company (HRRC) century old historic passenger rail stations ger rail station in a downtown area was has proposed re-establishing passenger rail may meet these needs and in other instances, finding sites with sufficient room for park- service between Danbury, Connecticut and new locations may better serve them. ing. Thus, for the recommended down- Pittsfield, Massachusetts on the former town passenger rail stations a smaller To address this issue, the Berkshire Regional Berkshire Line. The passenger rail service amount of parking, compared to a regional Planning Commission (BRPC) partnered between these two locations last operated passenger rail station, will likely be availa- with HRRC to conduct this passenger rail in 1971 shortly after the Penn Central ble. -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Alberta-To-Alaska-Railway-Pre-Feasibility-Study

Alberta to Alaska Railway Pre-Feasibility Study 2015 Table of Content Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... i Infrastructure and Operating Requirements................................................................ ii Environmental Considerations and Permitting Requirements .................................... ii Capital and Operating Cost Estimates ......................................................................... iii Business Case .............................................................................................................. iii Mineral Transportation Potential ................................................................................ iii First Nations/Tribes and Other Contacts ..................................................................... iv Conclusions .................................................................................................................. iv 1 | Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 This Assignment............................................................................................................ 1 This Report ................................................................................................................... 2 2 | Infrastructure and Operating Requirements ........................................................ 3 Route Alignment .......................................................................................................... -

MIT Kendall Square

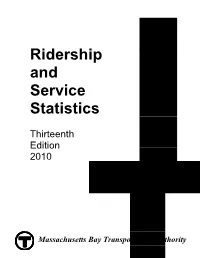

Ridership and Service Statistics Thirteenth Edition 2010 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile July 2010 MBTA Service District Cities and Towns 175 Size in Square Miles 3,244 Population (2000 Census) 4,663,565 Typical Weekday Ridership (FY 2010) By Line Unlinked Red Line 241,603 Orange Line 184,961 Blue Line 57,273 Total Heavy Rail 483,837 Total Green Line (Light Rail & Trolley) 236,096 Bus (includes Silver Line) 361,676 Silver Line SL1 & SL2* 14,940 Silver Line SL4 & SL5** 15,086 Trackless Trolley 12,364 Total Bus and Trackless Trolley 374,040 TOTAL MBTA-Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 System Unlinked MBTA - Provided Urban Service 1,093,973 Commuter Rail Boardings (Inbound + Outbound) 132,720 Contracted Bus 2,603 Water Transportation 4,372 THE RIDE Paratransit Trips Delivered 6,773 TOTAL ALL MODES UNLINKED 1,240,441 Notes: Unlinked trips are the number of passengers who board public transportation vehicles. Passengers are counted each time they board vehicles no matter how many vehicles they use to travel from their origin to their destination. * Average weekday ridership taken from 2009 CTPS surveys for Silver Line SL1 & SL2. ** SL4 service began in October 2009. Ridership represents a partial year of operation. File: CH 01 p02-7 - MBTA Service and Infrastructure Profile Jul10 1 Annual Ridership (FY 2010) Unlinked Trips by Mode Heavy Rail - Red Line 74,445,042 Total Heavy Rail - Orange Line 54,596,634 Heavy Rail Heavy Rail - Blue Line 17,876,009 146,917,685 Light Rail (includes Mattapan-Ashmont Trolley) 75,916,005 Bus (includes Silver Line) 108,088,300 Total Rubber Tire Trackless Trolley 3,438,160 111,526,460 TOTAL Subway & Bus/Trackless Trolley 334,360,150 Commuter Rail 36,930,089 THE RIDE Paratransit 2,095,932 Ferry (ex. -

Solent Connectivity May 2020

Solent Connectivity May 2020 Continuous Modular Strategic Planning Page | 1 Page | 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 The Solent CMSP Study ................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Scope and Geography....................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Fit with wider rail industry strategy ................................................................................................. 11 2.3 Governance and process .................................................................................................................. 12 3.0 Context and Strategic Questions ............................................................................................................ 15 3.1 Strategic Questions .......................................................................................................................... 15 3.2 Economic context ............................................................................................................................. 16 3.3 Travel patterns and changes over time ............................................................................................ 18 3.4 Dual-city region aspirations and city to city connectivity ................................................................ -

January 22, 2021 Board Meeting San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority

January 22, 2021 Board Meeting San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority ITEM 1 Call to Order, Pledge of Allegiance, Roll Call San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority ITEM 2 Consent Calendar 2.1 Approve Minutes from November 20, 2020 Board Meeting 2.2 Appoint New Members to San Joaquin Valley Rail Committee 2.3 Next Board Meeting Location 2.4 SJJPA Operating Expense Report 2.5 Blue Ribbon Task Force Letter 2.6 Washington Update 2.7 Administrative Items San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority ITEM 3 Public Comments Please use the GoToMeeting chat function to alert staff if you wish to make a Public Comment. Alternatively, you may write in your public comment to [email protected] and staff will read the comment aloud. Public comments should be limited to approximately two minutes and no more than 240 words per comment. San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority ITEM 4 Approve a Resolution of the Board of the San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority Adopting the Final Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration (Final IS/MND) for the Madera Station Relocation Project (Project), Adopting the Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program for the Project, Approving the Madera Station Relocation Project, Authorizing and Directing the Executive Director to Execute and File a Notice of Determination Under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for the Project, and Authorizing the Executive Director to Execute Any and All Documents Related to the Project (Dan Leavitt) Madera Station Relocation Project Background . Existing Madera San Joaquins Station located in vicinity of Madera Acres . Proposed Station located just north of Avenue 12 along the existing BNSF tracks CEQA Process Schedule . -

Concord Coach (NH) O Dartmouth Coach (NH) O Peter Pan Bus Lines (MA)

KFH GROUP, INC. 2012 Vermont Public Transit Policy Plan INTERCITY BUS NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND POLICY OPTIONS White Paper January, 2012 Prepared for the: State of Vermont Agency of Transportation 4920 Elm Street, Suite 350 —Bethesda, MD 20814 —(301) 951-8660—FAX (301) 951-0026 Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Background and Policy Context......................................................................... 1-1 Policy Context...................................................................................................................... 1-1 Chapter 2: Inventory of Existing Intercity Passenger Services.......................................... 2-1 Intercity Bus......................................................................................................................... 2-1 Impacts of the Loss of Rural Intercity Bus Service......................................................... 2-8 Intercity Passenger Rail.................................................................................................... 2-11 Regional Transit Connections ......................................................................................... 2-11 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 2-13 Chapter 3: Analysis of Intercity Bus Service Needs............................................................ 3-1 Demographic Analysis of Intercity Bus Needs............................................................... 3-1 Public Input on Transit Needs ....................................................................................... -

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142)

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) New Hampshire Historic Property Documentation An historical study of the railroad overpass on Exeter Road near the center of Hampton. Preservation Company 5 Hobbs Road Kensington, N.H. 2004 NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORIC PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION EXETER ROAD BRIDGE (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) NH STATE NO. 608 Location: Eastern Railroad/Boston and Maine Eastern Division at Exeter Road in Hampton, New Hampshire (Milepost 46.59), Rockingham County Date of Construction: Abutments 1900; bridge reconstructed ca. 1926 Engineer: Boston & Maine Engineering Department Present Owner: State of New Hampshire Department of Transportation John Morton Building, 1 Hazen Drive Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Present Use: Vehicular Overpass over Railroad Tracks Significance: This single-span wood stringer bridge with stone abutments is typical of early twentieth century railroad bridge construction in New Hampshire and was a common form used throughout the state. The crossing has been at the same site since the railroad first came through the area in 1840 and was the site of dense commercial development. The overpass and stone abutments date to 1900 when the previous at-grade crossing was eliminated. The construction of the bridge required the wholesale shifting of Hampton Village's commercial center to its current location along Route 1/Lafayette Road. Project Information: This narrative was prepared beginning in 2004, to accompany a series of black-and-white photographs taken by Charley Freiberg in August 2004 to record the Exeter Road Bridge. The bridge is located on, and a contributing element to, the Eastern Railroad Historic District, which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, and C as a linear transportation district on May 3, 2002. -

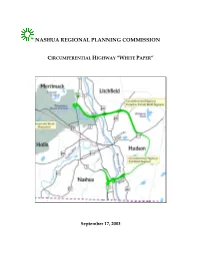

NRPC White Paper on the Nashua-Hudson Circumferential

NASHUA REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION CIRCUMFERENTIAL HIGHWAY “WHITE PAPER” September 17, 2003 NASHUA REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION CIRCUMFERENTIAL HIGHWAY “WHITE PAPER” September 17, 2003 INTRODUCTION The Nashua Regional Planning Commission is currently evaluating the proposed Hudson-Nashua Circumferential Highway project. Due to a number of factors, NRPC feels that it is prudent for the affected municipalities (Hudson, Litchfield, Merrimack and Nashua) and the general public to take a step back and reassess to this project. 1) The project has been moved out of the first ten years of the State’s Ten Year Transportation Improvement Plan (“Ten Year Plan”) due to state transportation funding constraints. 2) The most expensive part of the project is the portion that connects Route 3/DW Highway in Merrimack with the Everett Turnpike (which is within the Pennichuck Watershed). 3) Political support for the project is unclear. 4) The permitting process has been long and ongoing, and is not resulting in closure on this controversial project. 5) The project as proposed is likely to hit stiff opposition from environmental groups and from communities within the Pennichuck Brook Watershed, as a portion of the highway will be built within that watershed. 6) Central Hudson and downtown Nashua continue to experience significant traffic congestion, and a viable relief is needed. 7) There have been major changes to the region’s transportation plans since the project was originally conceived. 8) The NHDOT has acquired right-of-way for the partial build, and Hudson, Litchfield and Merrimack have included the alignment in their master plans. Development proposals are required to accommodate the right-of-way.