A Contested Chronology of the Yayoi-Kofun Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Volume 19 (2012), Article 2

Volume 19 (2012), Article 2 http://chinajapan.org/articles/19/2 Fogel, Joshua A. “On Saeki Arikiyo’s Monumental Study of the ‘Treatise on the People of Wa’” Sino-Japanese Studies 19 (2012), article 2. Abstract: Saeki Ariyiko was one of the world’s premier historians of ancient Japanese and East Asian history. His knowledge of texts and his ability to use them in creative ways and thus bring antiquity to life were virtually unmatched. One of his last works was a reading of the single most commented upon text in Sino-Japanese historical and cultural relations, the Treatise on the People of Wa in the Chronicle of the Kingdom of Wei (known in Japan as Gishi Wajinden). Saeki’s book, entitled Gishi Wajingden o yomu 魏 志倭人伝を読む (Reading the Treatise on the People of Wa in the Chronicle of the Kingdom of Wei), appeared in two volumes (over 450 pages in total) and was published by Yoshikawa kōbunkan in 2000. To give a flavor of the work, I offer a translation of the introductions to each of the volumes. Sino-Japanese Studies http://chinajapan.org/articles/19/2 On Saeki Arikiyo’s Monumental Study of the “Treatise on the People of Wa” Joshua A. Fogel Saeki Ariyiko 佐伯有清 (1925-2005) was one of the world’s premier historians of ancient Japanese and East Asian history. His knowledge of texts and his ability to use them in creative ways and thus bring antiquity to life were virtually unmatched. Although I never had the honor to study with or even meet him, I have long been an admirer of his scholarship both for his approach and product. -

Muko City, Kyoto

Muko city, Kyoto 1 Section 1 Nature and(Geographical Environment and Weather) 1. Geographical Environment Muko city is located at the southwest part of the Kyoto Basin. Traveling the Yodo River upward from the Osaka Bay through the narrow area between Mt. Tenno, the famous warfield of Battle of Yamazaki that determined the future of this country, and Mt. Otoko, the home of Iwashimizu Hachimangu Shrine, one of the three major hachimangu shrines in Japan, the city sits where three rivers of the Katsura, the Uji and the Kizu merge and form the Yodo River. On west, Kyoto Nishiyama Mountain Range including Mt. Oshio lays and the Katsura River runs on our east. We share three boundaries with Kyoto city - the northern and western boundaries with Nishikyo-ku, and the eastern boundary with Minami-ku and Fushimi-ku. Across the southern boundary is Nagaokakyo city abutting Oyamazaki-cho which is the neighbor of Osaka Prefecture. The city is approximiately 2km from east to west and approximiately 4km from south to north covering the 7.72km2 area. This makes us the third smallest city in Japan after Warabi city and Komae city. Figure 1-1-1 Location of Muko city (Right figure (Kyoto map) : The place of red is Muko city) (Lower figure (Japan map) : The place of red is Kyoto) N W E S 1 Geographically, it is a flatland with the northwestern part higher and the southwestern part lower. This divides the city coverage into three distinctive parts of the hilly area in the west formed by the Osaka Geo Group which is believed to be cumulated several tens of thousands to several million years ago, the terrace in the center, and the alluvial plain in the east formed by the Katsura River and the Obata River. -

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan [ Main Document ] 2018 JAPAN Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive Summary 1. State Party Japan 2. State, Province or Region Osaka Prefecture 3. Name of the Property Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan 4. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second Table e-1 Component parts of the nominated property and their locations Coordinate of the central point ID Name of the No. component part Region / District Latitude Longitude 1 Hanzei-tenno-ryo Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 34” E 135° 29’ 18” Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun, Chayama Kofun and Daianjiyama Kofun 2-1 Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun 2 Sakai City N 34° 33’ 53” E 135° 29’ 16” 2-2 Chayama Kofun 2-3 Daianjiyama Kofun 3 Nagayama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 05” E 135° 29’ 12” 4 Genemonyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 54” E 135° 29’ 28” 5 Tsukamawari Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 46” E 135° 29’ 26” 6 Osamezuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 31” E 135° 29’ 16” 7 Magodayuyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 36” E 135° 29’ 06” 8 Tatsusayama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 40” E 135° 29’ 00” 9 Dogameyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 46” E 135° 28’ 56” 10 Komoyamazuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 01” E 135° 29’ 03” 11 Maruhoyama Kofun Sakai City N 34° 34’ 01” E 135° 29’ 07” 12 Nagatsuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 29” E 135° 29’ 16” 13 Hatazuka Kofun Sakai City N 34° 33’ 24” E 135° 28’ 58” Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group e 001 Executive Summary Coordinate of the central point ID Name of the No. -

The Creation of National Treasures and Monuments: the 1916 Japanese Laws on the Preservation of Korean Remains and Relics and Their Colonial Legacies Hyung Il Pai

The Creation of National Treasures and Monuments: The 1916 Japanese Laws on the Preservation of Korean Remains and Relics and Their Colonial Legacies Hyung Il Pai This article surveys the history of Korea’s heritage management laws and administration beginning with the current divisions of the Office of Cultural Properties and tracing its structure back to the 1916 Japanese Preservations Laws governing Korean remains and relics. It focuses on the eighty-year-old bureaucratic process that has led to the creation of a distinct Korean patrimony, now codified and ranked in the nationally designated registry of cultural properties (Chijông munhwajae). Due to the long-standing perceived “authentic” status of this sanctified list of widely recognized “Korean” national treasures, they have been preserved, reconstructed, and exhibited as tangible symbols of Korean identity and antiquity since the early colonial era. The Office of Cultural Properties and the Creation of Korean Civilization The Office of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae Kwalliguk, hereafter re- ferred to as the OCP) since its foundation in 1961 has been the main institution responsible for the legislation, identification, registration, collection, preserva- tion, excavations, reconstruction and exhibitions of national treasures, archi- tectural monuments, and folk resources in the Republic of Korea.1 This office used to operate under the Ministry of Culture and Sports, but, due to its ever- expanding role, it was awarded independent ministry (ch’ông) status in 1998. With a working staff of more than five hundred employees, it also oversees a vast administrative structure including the following prominent cultural insti- tutions: the Research Institute of Cultural Properties (Munhwajae Yôn’guso) founded in 1975; the two central museums, the National and Folk Museum, which are in charge of an extended network of nine national museums (located in Kyôngju, Kwangju, Chônju, Ch’ôngju, Puyô, Kongju, Taegu, Kimhae, and Korean Studies, Volume 25, No. -

A Historical Analysis of the Traditional Japanese Decision-Making Process in Contrast with the U.S

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1976 A historical analysis of the traditional Japanese decision-making process in contrast with the U.S. system and implications for intercultural deliberations Shoji Mitarai Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mitarai, Shoji, "A historical analysis of the traditional Japanese decision-making process in contrast with the U.S. system and implications for intercultural deliberations" (1976). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2361. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2358 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Shoji Mitarai for the Master of Arts in Speech Conununication presented February 16, 1976. Title: A Historical Analysis of the Traditional Japanese Decision-Maki~g Process in Contrast with the U.S. System and Implications for Intercultural Delibera tions. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEES: The purpose of this research.is to (1) describe and analyze the different methods used by Japanese ·and by U.S. persons to reach ~greement in small. group deliberations, (2) discover the depth of ·conunitment and personal involvement with th~se methods by tracing their historical b~ginni~gs, and (3) draw implications 2 from (1) and (2) as to probability of success of current problem solving deliberations involving members of both ·groups. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

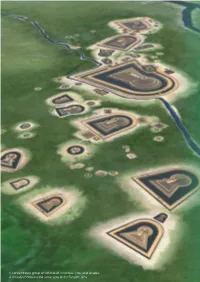

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group

Mahorashiroyama Yamatogawa River Sakai-Higashi Sakaishi Sakai Exit [Exhibition facility] 南海本線 Shukuin 170 WORLD HERITAGE SITE What is kofun? Terajicho Sakai City Hall What is the Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group? Observatory Lobby Osaka Chuo Loop Line 170 Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun Sakai-Yamatotakada Line Fujiidera Public Library Kofun is a collective term for the ancient tombs with earthen mounds that 湊 御陵前 [Exhibition facility] The World Heritage property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb Ryonannomori Synthesis Pyramid of Cheops Fujiidera Center 12 Fujiidera City Hall were actively constructed in the Japanese archipelago from the middle of 26 I.C. Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group group of the king’s clan that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago. Mausoleum of [Exhibition facility] the 3rd century to the late 6th century CE. In those days, members of the Hajinosato The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late the First Qin Emperor 30 Takawashi Fujiidera high-ranking elite were buried in kofun. Kintetsu Minami-Osaka Line Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period. They are located Mikunigaoka in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important Domyoji A burial mound was constructed by heaping up the soil that was dug 197 AICEL Shura Hall political cultural centers and a maritime gateway to the Asian continent. from the ground around the mound site. The sloping sides of the mound [Exhibition facility] were covered with stones, and the excavated area formed a moat, Mozuhachiman The kofun group includes many tombs in the shape of a keyhole, descending to a level lower than any other part of the tomb. -

Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1992 19/2-3 Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period I s h in o H ironobu 石野博信 The rituals of the Kofun period were closely connected with both daily life and political affairs. The chieftain presided over the principal rites, whether in the mountains, on the rivers, or along the roadsides. The chieftain’s funeral was the preeminent rite, with a tomb mound, or kofun, constructed as its finale. The many and varied kofun rituals have been discussed elsewhere;1 here I shall concentrate on other kami rites and their departure from Yayoi practices. A Ritual Revolution Around AD 190, following a period of warfare called the “Wa Unrest,” the overall leadership of Wa was assumed by Himiko [Pimiko], female ruler of the petty kingdom of Yamatai. Beginning in 239 she opened diplomatic relations with the Wei court in China as the monarch of Wa, and she died around 248. Makimuku 1 type pottery appeared around 190; in 220 or so it was followed by Makimuku 2,and then by Makimuku 3, in about 250. The 92-meter-long keyhole-shaped Makimuku Ishizuka tomb in Sakurai City, Nara, was constructed in the first half of the third century; in the latter half of the same century the Hashihaka tomb was built. Hence the reign of Himiko, circa 190 to 248,corresponds to the appearance of key hole-shaped tombs. It was the dawn of the Kofun period and a formative time in Kofun-period ritual. In the Initial Kofun, by which I mean the period traditionally assigned to the very end of the Yayoi, bronze ritual objects were smashed, dis * This article is a partial translation of the introductory essay to volume 3 of Ish in o et al. -

Japan: Yayoi Period (About 300 BC - AD 300)

Japan: Yayoi period (about 300 BC - AD 300) The Yayoi period takes its name from the Yayoi district of Tokyo where simple pottery differing significantly in style from earlier Jōmon wares, was first discovered in 1884. The Yayoi period was a time of significant change, from hunting and gathering to a settled, agricultural way of life. Wet-rice agriculture and bronze and iron were introduced from the continent (Korea and China), probably by individual peaceful settlement, rather than hostile invasion. With the establishment of small kuni (farming settlements) came the beginnings of complex regional politics and a simple class system. There was a systemization of animist religious beliefs. Armed conflict over territory dates from about the third century AD. Most of our knowledge of this period comes through archaeology, but written Chinese documents also give valuable insights. The Han shu (late first century AD) describes Japan as a land of about 100 small kuni which sent tribute to the Han court. A gold seal found in Japan in 1784 was probably the one presented to a local ruler in northern Kyūshū by Emperor Guangwu (Kuang-wu) in AD 57. The third-century Wei zhi describes Japanese culture and mentions the kuni of Yamatai which became dominant during the Kofun period. Most of the pottery of the period, with its characteristic combed designs, was used for cooking, eating and storage of grain. However, burial urns up to 76 cm in height have also been found. Rice, millet, beans and gourds were grown around settlements of thatched pit houses, granaries and wells.