Theory, with Special Attention to Moving-Image Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibits Registrations

July ‘09 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY TUESDAY SATURDAY ART ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBERS’ 6 14 “STREET ANGEL” (1928-101 min.). In HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free 18 SHOW, throughout the summer. AAC MANHASSET BAY BOAT TOURS: Have “laughter-loving, careless, sordid Naples,” screening by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. a look at Manhasset Bay – from the water! In the Photography Gallery a fugitive named Angela (Oscar winner to 2 p.m. A free 90-minute boat tour will explore Janet Gaynor) joins a circus and falls in Legendary Long the history and ecology of our corner of love with a vagabond painter named Gino TOPICAL TUESDAY: Islanders. What do Billy Joel, Martha Stew- Long Island Sound. Tour dates are July (Charles Farrell). Philip Klein and Henry art, Kiri Te Kanawa and astronaut Dr. Mary 18; August 8 and 29. The tour is free, but Roberts Symonds scripted, from a novel Cleave have in common? They have all you must register at the Information Desk by Monckton Hoffe, for director Frank lived on Long Island and were interviewed for the 30 available seats. Registration for Borzage. Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano by Helene Herzig when she was feature the July 18 tour begins July 2; Registration provided the glistening cinematography. editor of North Shore Magazine. Herzig has for the August tours begins July 21. Phone Silent with orchestral score. 7:30 p.m. collected more than 70 of her interviews, registration is acceptable. Tours at 1 and written over a 20-year period. The celebri- 3 p.m. Call 883-4400, Ext. -

Film Essay for "7Th Heaven"

7th Heaven By Aubrey Solomon In the years between 1926 and 1928, Hollywood ex- perienced a maturation which blended art and indus- try to a new level of cinema. Influenced heavily by the experiments of foreign talents, largely German, new concepts of cinematography, lighting, set de- sign, and special effects known as “trick shots,” per- meated American film-making methods. The somber and sometimes morbid themes of German cinema also seeped into their films, often to the chagrin of American exhibitors who preferred their own exuber- ant optimism and happy endings. “7th Heaven” characterizes a perfect blend of opti- mistic romantic fantasy and German influenced pro- duction design. It also became one of the most pop- ular films of the late silent era. Its opening title card set the tone: “For those who will climb it, there is a ladder leading from the depths to the heights - from the sewer to the stars - the ladder of Courage.” Based on a hugely successful play by Austin Strong which ran at the Booth Theatre on Broadway from October 30, 1922, to May 21,1924 for a total of 685 performances, it portrayed the travails of young lov- An advertisement from a June 1927 edition of Motion ers who meet amidst the sordid gutters of pre-World Picture News. Courtesy Media History Digital Library. War I Paris. Happy-go-lucky street cleaner Chico saves waifish, homeless, Diane, a runaway from her abusive sister. Against Chico’s initial resistance, he Fox Films vice-president and general manager falls in love with Diane only to end up going to war Winfield Sheehan acknowledged audiences were and being declared dead in battle. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

The People's Institute, the National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America

In Defense of the Moving Pictures: The People's Institute, The National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America Nancy J, Rosenbloom Located in the midst of a vibrant and ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood on New York's Lower East Side, the People's Institute had by 1909 earned a reputation as a maverick among community organizations.1 Under the leadership of Charles Sprague Smith, its founder and managing director, the Institute supported a number of political and cultural activities for the immigrant and working classes. Among the projects to which Sprague Smith committed the People's Institute was the National Board of Censorship of Motion Pictures. From its creation in June 1909 two things were unusual about the National Board of Censorship. First, its name to the contrary, the Board opposed growing pressures for legalized censorship; instead it sought the voluntary cooperation of the industry in a plan aimed at improving the quality and quantity of pictures produced. Second, the Board's close affiliation with the People's Institute from 1909 to 1915 was informed by a set of assumptions about the social usefulness of moving pictures that set it apart from many of the ideas dominating American reform. In positioning itself to defend the moving picture industry, the New York- based Board developed a national profile and entered into a close alliance with the newly formed Motion Picture Patents Company. What resulted was a partnership between businessmen and reformers that sought to offset middle-class criticism of the medium. The officers of the Motion Picture Patents Company also hoped 0026-3079/92/3302-O41$1.50/0 41 to increase middle-class patronage of the moving pictures through their support of the National Board. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Festa Del Cinema Di Roma FESTA DEL CINEMA DI ROMA 13/23 OTTOBRE 2016

11A Festa del Cinema di Roma FESTA DEL CINEMA DI ROMA 13/23 OTTOBRE 2016 FONDATORI PRESIDENTE Roma Capitale Piera Detassis Regione Lazio Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale Camera di Commercio di Roma DIRETTORE GENERALE Fondazione Musica per Roma Francesca Via Istituto Luce Cinecittà S.r.l DIRETTORE ARTISTICO COLLEGIO DEI FONDATORI Antonio Monda Presidente Lorenzo Tagliavanti Presidente della Camera di Commercio di Roma COMITATO DI SELEZIONE Virginia Raggi Mario Sesti, Coordinatore Sindaca di Roma Capitale Valerio Carocci e della Città Metropolitana Alberto Crespi Giovanna Fulvi Nicola Zingaretti Richard Peña Presidente della Regione Lazio Francesco Zippel Aurelio Regina Presidente della Fondazione Musica per Roma Roberto Cicutto Presidente dell’Istituto Luce Cinecittà CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE RESPONSABILE UFFICIO CINEMA Piera Detassis, Presidente Alessandra Fontemaggi Laura Delli Colli Lorenzo Tagliavanti José Ramón Dosal Noriega Roberto Cicutto COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Roberto Mengoni, Presidente Massimo Gentile, Revisore Effettivo Giovanni Sapia, Revisore Effettivo Maurizio Branco, Revisore Supplente Marco Buttarelli, Revisore Supplente A FESTA 13-23 DEL CINEMA OTTOBRE 11 DI ROMA 2016 Prodotto da Main Partner Promosso da Partner Istituzionali Con il supporto di In collaborazione con Official sponsor Partner Tecnico Eco Mobility Partner Sponsor di Servizi Media Partner Partner Culturali Sponsor2.1 Invicta institutional logo “Since” 2.1.1 Dimensions, proportions and colour references The Invicta corporate logo is made up of 2 colours, blue and red. The Invicta corporate logo must never be modified or reconstructed. FOOD PROMOTION & EVENTS MANAGEMENT 26x 8x 87x 1x 15x 31x 2x 3x 5x 3x 1x Pantone 33xCMYK Pantone RGB 2x Textile 20x Invicta red C: 0 4852x C P. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

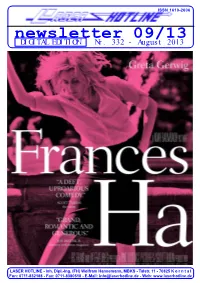

Newsletter 09/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 09/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 332 - August 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 09/13 (Nr. 332) August 2013 editorial Neues Video auf unserem Youtube-Kanal! http://www.youtube.com/user/laserhotline WOCHENENDKRIEGER DIE FILMMUSIK Wir haben Uwe Schenk, den Komponisten der Musik zu dem Film „Wochenendkrieger“, in seinem Studio besucht. Anhand von Beispielen demonstriert er seine Arbeitsweise und erzählt über den sinfonischen Score zu Andreas Geigers Dokumentarfilm. Viel Spaß bei Anschauen wünscht Ihr LASER HOTLINE Team! LASER HOTLINE Seite 2 Newsletter 09/13 (Nr. 332) August 2013 Batfleck and Wonder-Where-She-Is-Woman Vereinzelte Sonnenstrahlen scheinen durch die Wol- Joker gecastet wurde. Dass er sich in Batman verlie- kendecke durch und kitzeln mir das Gesicht. Schlaf- ben würde, wurde gehöhnt, und dass er die Persön- trunken greife ich nach meinem iPhone, reibe mir die lichkeit und schauspielerischen Fähigkeiten eines Augen und rufe mein Twitter auf. Das Internet ist in Blattes Salat habe. Und nun ist Ledgers Joker eine Rage, nur ein Thema beherrscht meine Timeline: Ben Legende und wird verehrt. Nicht nur, weil es seine Affleck ist offiziell der neue Batman! Missmut, Auf- letzte Performance war und er alles dafür gegeben ruhr, Revolution! Alle sind sich einig, dass Affleck der hat. Ben Affleck ist heutzutage ein weit besserer totale Fehlgriff für den Dunklen Ritter ist. Ich lege das Schauspieler als er es zu Zeiten von Jack Ryan und iPhone beiseite und stöhne.