Productivity Growth and the Regional Dynamics of Antebellum Southern Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXIX Fall/Winter 2017 No. 3 and No. 4 CONTENTS Death on a Summer Night: Faulkner at Byhalia 101 By Jack D. Elliott, Jr. and Sidney W. Bondurant The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, 137 and Slavery: 1848–1860 By Elias J. Baker William Leon Higgs: Mississippi Radical 163 By Charles Dollar 2017 Mississippi Historical Society Award Winners 189 Program of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 193 Annual Meeting By Brother Rogers Minutes of the 2017 Mississippi Historical Society 197 Business Meeting By Elbert R. Hilliard COVER IMAGE —William Faulkner on horseback. Courtesy of the Ed Meek digital photograph collection, J. D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. UNIV. OF MISS., THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, STUDENTS, AND SLAVERY 137 The University of Mississippi, the Board of Trustees, Students, and Slavery: 1848-1860 by Elias J. Baker The ongoing public and scholarly discussions about many Americans’ widespread ambivalence toward the nation’s relationship to slavery and persistent racial discrimination have connected pundits and observers from an array of fields and institutions. As the authors of Brown University’s report on slavery and justice suggest, however, there is an increasing recognition that universities and colleges must provide the leadership for efforts to increase understanding of the connections between state institutions of higher learning and slavery.1 To participate in this vital process the University of Mississippi needs a foundation of research about the school’s own participation in slavery and racial injustice. The visible legacies of the school’s Confederate past are plenty, including monuments, statues, building names, and even a cemetery. -

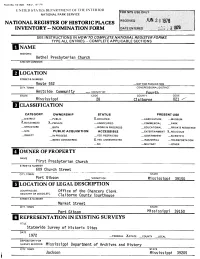

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9 '77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Bethel Presbyterian Church AND/OR COMMON LOCATION .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wests ide Community __.VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Clai borne 021 ^*" BfCLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) X_PR| VATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME First Presbyterian Church STREET & NUMBER 609 Church Street CITY, TOWN STATE Port Gibson VICINITY OF Mississippi 39150 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. Office of the Chancery Clerk REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. C1a1borne STREET & NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Port Gibson Mississippi 39150 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Statewide Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1972 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Mississippi Department of Archives and History CITY. TOWN STATE Jackson Mississippi 39205 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Bethel Presbyterian Church, facing southwest on a grassy knoll on the east side of Route 552 north of Alcorn and approximately three miles from the Mississippi River shore, is representative of the classical symmetry and gravity expressed in the Greek Revival style. -

Land Use Legacies and the Future of Southern Appalachia

Society and Natural Resources, 19:175-190 Taylor & Francis Copyright 02006 Taylor & Francis LLC ,,&F,Grn", ISSN: 0894-1920 print/ 1521-0723 online 0 DOI: 10.1080/08941920500394857 Land Use Legacies and the Future of Southern Appalachia TED L. GRAGSON Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA PAUL V. BOLSTAD Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA Southern Appalachian forests have apparently recovered from extractive land use practices during the 19th and 20th centuries, yet the legacy of this use endures in terrestrial and aquatic systems of the region. Thefocus on shallow time or the telling of stories about the past circumscribes the ability to anticipate the most likely out- comes of the trajectory of changeforecast for the Southeast as the "Old South" con- tinues its transformation into the "New South." We review land use research of the Coweeta Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) project that addresses the nature and extent of past andpresent human land use, how land use has affected the struc- ture and function of terrestrial and aquatic communities, and the forces guiding the anticipated trajectory of change. Unlike development in the western or northeastern regions of the United States, the southeastern region has few practical, political, or geographical boundaries to the urban sprawl that is now developing. Keywords aquatic communities, land use, land-use decision making, legacy, reforestation, southern Appalachia, terrestrial communities, urban sprawl In different locations around the world and for diverse reasons, lands once dedicated to extractive use have been abandoned and forest vegetation has expanded (e.g., Foster 1992). -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

Buck-Horned Snakes and Possum Women: Non-White Folkore, Antebellum *Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2010 Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange John Douglas Miller College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Miller, John Douglas, "Buck-horned snakes and possum women: Non-white folkore, antebellum *Southern literature, and interracial cultural exchange" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623556. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-rw5m-5c35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. BUCK-HORNED SNAKES AND POSSUM WOMEN Non-White Folklore, Antebellum Southern Literature, and Interracial Cultural Exchange John Douglas Miller Portsmouth, Virginia Auburn University, M.A., 2002 Virginia Commonwealth University, B.A., 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2010 ©Copyright John D. Miller 2009 APPROVAL SHEET This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by the Committee, August 21, 2009 Professor Robert J. Scholnick, American Studies Program The College of William & Mary Professor Susan V. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas. Justin Garrett Orh Ton East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2007 The econdS Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas. Justin Garrett orH ton East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Horton, Justin Garrett, "The eS cond Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2025. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2025 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Second Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas ___________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History ______________________________________ by Justin Horton August 2007 ____________________________________ Melvin Page, Chair Tom Lee Doug Burgess Keywords: Manifest Destiny, Brazil, Mexico, colonization, emigration, Venezuela, Confederate States of America, Southern Nationalism ABSTRACT The Second Lost Cause: Post-National Confederate Imperialism in the Americas by Justin Horton At the close of the American Civil War some southerners unwilling to remain in a reconstructed South, elected to immigrate to areas of Central and South America to reestablish a Southern antebellum lifestyle. -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

Declarations of Independence Since 1776* DAVID ARMITAGE Harvard

South African Historical Journal, 52 (2005), 1-18 The Contagion of Sovereignty: Declarations of Independence since 1776* DAVID ARMITAGE Harvard University The great political fact of global history in the last 500 years is the emergence of a world of states from a world of empires. That fact – more than the expansion of democracy, more than nationalism, more than the language of rights, more even than globalisation – fundamentally defines the political universe we all inhabit. States have jurisdiction over every part of the Earth’s land surface, with the exception of Antarctica. The only states of exception – such as Guantánamo Bay – are the exceptions created by states.1 At least potentially, states also have jurisdiction over every inhabitant of the planet: to be a stateless person is to wander an inhospitable world in quest of a state’s protection. An increasing number of the states that make up that world have adopted democratic systems of representation and consultation, though many competing, even inconsistent, versions of democracy can exist beneath the carapace of the state.2 Groups that identify themselves as nations have consistently sought to realise their identities through assertions of statehood. The inhabitants of the resulting states have increasingly made their claims to representation and consultation in the language of rights. Globalisation has made possible the proliferation of the structures of democracy and of the language of rights just as it has helped to spread statehood around the world. Yet all of these developments – democratisation, nationalism, the diffusion of rights-talk and globalisation itself – have had to contend with the stubbornness of states as the basic datum of political existence. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Alan Gallay Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History Tel. (817) 257-6299 Department of History and Geography Office: Reed Hall 303 Texas Christian University e-mail: [email protected] Fort Worth, TX 76129 Education Ph.D. Georgetown University, April 1986. Dissertation: “Jonathan Bryan and the Formation of a Planter Elite in South Carolina and Georgia, 1730-1780.” Awarded Distinction M.A. Georgetown University, November 1981 B.A. University of Florida, March 1978, Awarded High Honors Professional Experience Lyndon B. Johnson Chair of U.S. History, Texas Christian University, 2012- Warner R. Woodring Chair of Atlantic World and Early American History, Ohio State University, 2004- 2012 Director, The Center for Historical Research, Ohio State University, 2006-2011 Professor of History, 1995-2004; Associate Professor of History, 1991-1995, Assistant Professor of History, Western Washington University, 1988- 1991 American Heritage Association Professor for London, Fall 1996, Fall 1999 Visiting Lecturer, Department of History, University of Auckland, 1992 Visiting Professor, Departments of Afro-American Studies and History, Harvard University, 1990-1991 Visiting Assistant Professor of History and Southern Studies, University of Mississippi, 1987-1988 Visiting Assistant Professor of History, University of Notre Dame, 1986- 1987 Instructor, Georgetown University, Fall 1983; Summer 1984; Summer 1986 Instructor, Prince George’s Community College, Fall 1983 Teaching Assistant, Georgetown University, 1979-1983 1 Academic Honors Historic -

Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move Ronald J. McCall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McCall, Ronald J., "Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1121. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1121 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move __________________________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ___________________________ by Ronald J. McCall May 2013 ________________________ Dr. Steven N. Nash, Chair Dr. Tom D. Lee Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Family History, Southern Plain Folk, Herder, Mississippi Territory ABSTRACT Never Quite Settled: Southern Plain Folk on the Move by Ronald J. McCall This thesis explores the settlement of the Mississippi Territory through the eyes of John Hailes, a Southern yeoman farmer, from 1813 until his death in 1859. This is a family history. As such, the goal of this paper is to reconstruct John’s life to better understand who he was, why he left South Carolina, how he made a living in Mississippi, and to determine a degree of upward mobility. -

The Domestic Slave Trade

Lesson Plan: The Domestic Slave Trade Intended Audience Students in Grades 8-12 Background The importation of slaves to the United States from foreign countries was outlawed by the Act of March 2, 1807. After January 1, 1808, it was illegal to import slaves; however, the domestic slave trade thrived within the United States. With the rise of cotton in the Deep South slaves were moved and traded from state to state. Slaves were treated as commodities and listed as such on ship manifests as cargo. Slave manifests included such information as slaves’ names, ages, heights, sex and “class”. This lesson introduces students to the domestic slave trade between the states by analyzing slave manifest records of ships coming and going through the port of New Orleans, Louisiana. The Documents Slave Manifest of the Brig Algerine, March 25, 1826; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Slave Manifest of the Brig Virginia, November 18, 1823; Slave Manifests, 1817-1856 and 1860-1861 (E. 1630); Records of the U.S. Customs Service—New Orleans, Record Group 36; National Archives at Fort Worth. Standards Correlations This lesson correlates to the National History Standards. Era 4 Expansion and Reform (1801-1861) ○ Standard 2-How the industrial revolution, increasing immigration, the rapid expansion of slavery and the westward movement changed the lives of Americans and led toward regional tensions. Teaching Activities Time Required: One class period Materials Needed: Copies of the Documents Copies of the Document Analysis worksheet Analyzing the Documents Provide each student with a copy of the Written Document Analysis worksheet.