3. Allen, Holy Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pete Seegerhas Always Walked the Road Less Traveled. a Tall, Lean Fellow

Pete Seegerhas always walked the road less traveled. A tall, lean fellow with long arms and legs, high energy and a contagious joy of spjrit, he set everything in motion, singing in that magical voice, his head thrown back as though calling to the heavens, makingyou see that you can change the world, risk everything, do your best, cast away stones. “Bells of Rhymney,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “ One Grain of Sand,” “ Oh, Had I a Golden Thread” ^ songs Right, from top: Seeger, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie (from left) at the Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert at Carnegie Hail, 1967; filming “Wasn’t That a Time?," a movie of the Weavers’ 19 8 0 reunion; Seeger with banjo; at Red Above: The Weavers in the early ’50s - Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman (from left). Left: Seeger singing on a Rocks, in hillside in El Colorado, 1983; Cerrito, C a l|p in singing for the early '60s. Eleanor Roosevelt, et al., at the opening of the Washington Labor Canteen, 1944; aboard the “Clearwater” on his beloved Hudson River; and a recent photo of Seeger sporting skimmer (above), Above: The Almanac Singers in 1 9 4 1 , with Woody Guthrie on the far left, and Seeger playing banjo. Left: Seeger with his mother, the late Constance Seeger. PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE COLLECTION OF HAROLD LEVENTHAL AND THE WOODY GUTHRIE ARCHIVES scattered along our path made with the Weavers - floor behind the couch as ever, while a retinue of like jewels, from the Ronnie Gilbert, Fred in the New York offices his friends performed present into the past, and Hellerman and Lee Hays - of Harold Leventhal, our “ Turn Turn Turn,” back, along the road to swept into listeners’ mutual manager. -

Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968)

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Carney, “With Electric Breath” “With Electric Breath”: Bob Dylan and the Reimagining of Woody Guthrie (January 1968) Court Carney In 1956, police in New Jersey apprehended Woody Guthrie on the presumption of vagrancy. Then in his mid-40s, Guthrie would spend the next (and last) eleven years of his life in various hospitals: Greystone Park in New Jersey, Brooklyn State Hospital, and, finally, the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, where he died. Woody suffered since the late 1940s when the symptoms of Huntington’s disease first appeared—symptoms that were often confused with alcoholism or mental instability. As Guthrie disappeared from public view in the late 1950s, 1,300 miles away, Bob Dylan was in Hibbing, Minnesota, learning to play doo-wop and Little Richard covers. 1 Young Dylan was about to have his career path illuminated after attending one of Buddy Holly’s final shows. By the time Dylan reached New York in 1961, heavily under the influence of Woody’s music, Guthrie had been hospitalized for almost five years and with his motor skills greatly deteriorated. This meeting between the still stylistically unformed Dylan and Woody—far removed from his 1940s heyday—had the makings of myth, regardless of the blurred details. Whatever transpired between them, the pilgrimage to Woody transfixed Dylan, and the young Minnesotan would go on to model his early career on the elder songwriter’s legacy. More than any other of Woody’s acolytes, Dylan grasped the totality of Guthrie’s vision. Beyond mimicry (and Dylan carefully emulated Woody’s accent, mannerisms, and poses), Dylan almost preternaturally understood the larger implication of Guthrie in ways that eluded other singers and writers at the time.2 As his career took off, however, Dylan began to slough off the more obvious Guthrieisms as he moved towards his electric-charged poetry of 1965-1966. -

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 the Contemporary Jewish Muse

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 The Contemporary Jewish Museum San Francisco 2015 Sokołów, video; 2 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York Letters to Afar is made possible with generous support from the following sponsors: POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Museum of the City of New York Kronhill Pletka Foundation New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Righteous Persons Foundation Seedlings Foundation Mr. Sigmund Rolat The Contemporary Jewish Museum Patron Sponsorship: Major Sponsorship: Anonymous Donor David Berg Foundation Gaia Fund Siesel Maibach Righteous Persons Foundation Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Anita and Ronald Wornick Major support for The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibitions and Jewish Peoplehood Programs comes from the Koret Foundation. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw 05.18.2013 - 09.30.2013 Museum of the City of New York 10.22.2014 - 03.22.2015 The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco 02.26.2015 - 05.24.2015 Video installation by Péter Forgács with music by The Klezmatics, commissioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. The footage used comes from the collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, the National Film Archive in Warsaw, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Beit Hatfutsot in Tel Aviv and the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive in Jerusalem. 4 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics Kolbuszowa, video; 23 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York 6 7 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics beginning of the journey Andrzej Cudak The Museum of the History of Polish Jews invites you Acting Director on a journey to the Second Polish-Jewish Republic. -

“WOODY” GUTHRIE July 14, 1912 – October 3, 1967 American Singer-Songwriter and Folk Musician

2012 FESTIVAL Celebrating labour & the arts www.mayworks.org For further information contact the Workers Organizing Resource Centre 947-2220 KEEPING MANITOBA D GOING AN GROWING From Churchill to Emerson, over 32,000 MGEU members are there every day to keep our province going and growing. The MGEU is pleased to support MayWorks 2012. www.mgeu.ca Table of ConTenTs 2012 Mayworks CalendaR OF events ......................................................................................................... 3 2012 Mayworks sChedule OF events ......................................................................................................... 4 FeatuRe: woody guthRie ............................................................................................................................. 8 aCKnoWledgMenTs MAyWorkS BoArd 2012 Design: Public Service Alliance of Canada Doowah Design Inc. executive American Income Life Front cover art: Glenn Michalchuk, President; Manitoba Nurses Union Derek Black, Vice-President; Mike Ricardo Levins Morales Welfley, Secretary; Ken Kalturnyk, www.rlmarts.com Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 500 Financial Secretary Printing: Members Transcontinental Spot Graphics Canadian Union of Public Stan Rossowski; Mitch Podolak; Employees Local 3909 Hugo Torres-Cereceda; Rubin MAyWorkS PuBLIcITy MayWorks would also like to thank Kantorovich; Brian Campbell; the following for their ongoing Catherine Stearns Natanielle Felicitas support MAyWorkS ProgrAMME MAyWorkS FundErS (as oF The Workers Organizing Resource APrIL -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS February 22, 1973

5200 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS February 22, 1973 ORDER FOR RECOGNITION OF SEN be cousin, the junior Senator from West DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE ATOR ROBERT C. BYRD ON MON Virginia (Mr. ROBERT c. BYRD)' for a James N. Gabriel, of Massachusetts, to be DAY period of not to exceed 15 minutes; to be U.S. attorney for the district of Massachu Mr. ROBERT c. BYRD. I ask unani followed by a period for the transaction setts for the term of 4 years, vice Joseph L. mous consent that following the remarks of routine morning business of not to Tauro. exceed 30 minutes, with statements James F. Companion, of West Virginia, to of the distinguished senior Senator from be U.S. attorney for the northern district of Virginia (Mr. HARRY F. BYRD, JR.) on therein limited to 3 minutes, at the con West Virginia for the term of 4 years, vice Monday, his would-be cousin, Mr. RoB clusion of which the Senate will proceed Paul C. Camilletti, resigning. ERT C. BYRD, the junior Senator from to the consideration of House Joint Reso lution 345, the continuing resolution. IN THE MARINE CORPS West Virginia, the neighboring State just The following-named officers of the Marine over the mountains, be recognized for not I would anticipate that there would Corps for temporary appointment to the to exceed 15 minutes. likely be a rollcall vote--or rollcall grade of major general: The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without votes--in connection with that resolu Kenneth J. HoughtonJames R. Jones objection, it is so ordered. tion, but as to whether or not the Senate Frank C. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography

LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations William H. Hannon Library 8-2014 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey Gatten Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Gatten, Jeffrey, "The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography" (2014). LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations. 91. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs/91 This Article - On Campus Only is brought to you for free and open access by the William H. Hannon Library at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Music and Society, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 4, 464–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.834749 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey N. Gatten This bibliography updates two extensive works designed to include comprehensively all significant works by and about Woody Guthrie. Richard A. Reuss published A Woody Guthrie Bibliography, 1912–1967 in 1968 and Jeffrey N. Gatten’s article “Woody Guthrie: A Bibliographic Update, 1968–1986” appeared in 1988. With this current article, researchers need only utilize these three bibliographies to identify all English- language items of relevance related to, or written by, Guthrie. Introduction Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–67) was a singer, musician, composer, author, artist, radio personality, columnist, activist, and philosopher. By now, most anyone with interest knows the shorthand version of his biography: refugee from the Oklahoma dust bowl, California radio show performer, New York City socialist, musical documentarian of the Northwest, merchant marine, and finally decline and death from Huntington’s chorea. -

What Makes Klezmer So Special? Geraldine Auerbach Ponders the World Wide Popularity of Klezmer Written November 2009 for JMI Newsletter No 17

What Makes Klezmer so Special? Geraldine Auerbach ponders the world wide popularity of klezmer Written November 2009 for JMI Newsletter no 17 Picture this: Camden Town’s Jazz Café on 12 August 2009 with queues round the block including Lords of the realm, hippies, skull-capped portly gents, and trendy young men and women. What brought them all together? They were all coming to a concert of music called Klezmer! So what exactly is klezmer, and how, in the twenty-first century, does it still manage to resonate with and thrill the young and the old, the hip and the nostalgic, alike? In the 18th and 19th centuries, in the Jewish towns and villages of Eastern Europe the Yiddish term 'klezmer' referred to Jewish musicians themselves. They belonged to professional guilds and competed for work at weddings and parties for the Jewish community – as well as the local gentry. Their repertory included specific Jewish tunes as well as local hit songs played on the instruments popular in the locality. Performance was influenced by the ornamented vocal style of the synagogue cantor. When life became intolerable for Jews in Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century, and opportunity came for moving to newer worlds – musicians brought this music to the west, adapting all the while to immigrant tastes and the new recording scene. During the mid-twentieth century, this type of music fell from favour as the sons and daughters of Jewish immigrants turned to American and British popular styles. But just a few decades later, klezmer was back! A new generation of American musicians reclaimed the music of their predecessors. -

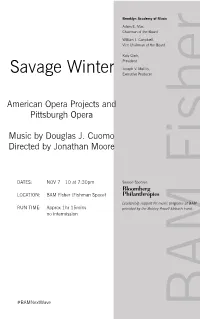

Savage Winter #Bamnextwave No Intermission LOCATION: RUN TIME: DATES: Pittsburgh Opera Approx 1Hr15mins BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) NOV 7—10At7:30Pm

Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Savage Winter Executive Producer American Opera Projects and Pittsburgh Opera Music by Douglas J. Cuomo Directed by Jonathan Moore DATES: NOV 7—10 at 7:30pm Season Sponsor: LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) Leadership support for music programs at BAM RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15mins provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund. no intermission #BAMNextWave BAM Fisher Savage Winter Written and Composed by Music Director This project is supported in part by an Douglas J. Cuomo Alan Johnson award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and funding from The Andrew Text based on the poem Winterreise by Production Manager W. Mellon Foundation. Significant project Wilhelm Müller Robert Signom III support was provided by the following: Ms. Michele Fabrizi, Dr. Freddie and Directed by Production Coordinator Hilda Fu, The James E. and Sharon C. Jonathan Moore Scott H. Schneider Rohr Foundation, Steve & Gail Mosites, David & Gabriela Porges, Fund for New Performers Technical Director and Innovative Programming and The Protagonist: Tony Boutté (tenor) Sean E. West Productions, Dr. Lisa Cibik and Bernie Guitar/Electronics: Douglas J. Cuomo Kobosky, Michele & Pat Atkins, James Conductor/Piano: Alan Johnson Stage Manager & Judith Matheny, Diana Reid & Marc Trumpet: Sir Frank London Melissa Robilotta Chazaud, Francois Bitz, Mr. & Mrs. John E. Traina, Mr. & Mrs. Demetrios Patrinos, Scenery and properties design Assistant Director Heinz Endowments, R.K. Mellon Brandon McNeel Liz Power Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. William F. Benter, Amy & David Michaliszyn, The Estate of Video design Assistant Stage Manager Jane E. -

Carmel Pine Cone, September 19, 2008

Late-night surprise: Mountain lion charges into woman’s bedroom By CHRIS COUNTS was reading in bed, ” recalled Jane Chanteau, who lives off “I hit him, and I yelled really loud,” she explained. Palo Colorado Road. “I woke up when my cat let out a horri- Much to the 73-year-old grandmother’s surprise, a lion SECONDS AFTER a late-night encounter with a moun- ble scream. It sounded like a cat fighting, only much louder.” pulled its head from beneath the bed. tain lion this week, a Big Sur house cat did the most logical Opening her eyes in the dimly lit bedroom, Chanteau “He jumped up on a box about four feet away, sat down thing possible — it scampered under its owner’s bed. thought she saw a dog chase her cat, a black and white 11- and just looked at me,” she said. “He wasn’t aggressive at all. Unfortunately for the cat, the mountain lion — following year-old named Bearli, under the bed. The intruder’s head He was calm.” close on its heels — tried to do the exact same thing. was also under the bed, so Chanteau gave him a good whack “It was about 11:30 p.m. Tuesday, and I dozed off while I on his behind. See LION page 9A BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID CARMEL, CA Permit No. 149 Volume 94 No. 38 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com September 19-25, 2008 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 Fierce advocate for historic buildings dies at 86 Kenney’s sentence to be By MARY BROWNFIELD with, because she had definite ideas about how she wanted things done,” said former Carmel City life without parole ENID SALES — a dedicated preservationist Councilwoman Barbara Livingston, who met touted as a hero by some and vilified by others for Sales more than 50 years ago when both were liv- ■ Convicted of two murders her fierce fights against the demolition of historic ing in the San Francisco Bay Area. -

(At) Miracosta

The Creative Music Recording Magazine Jeff Tweedy Wilco, The Loft, Producing, creating w/ Tom Schick Engineer at The Loft, Sear Sound Spencer Tweedy Playing drums with Mavis Staples & Tweedy Low at The Loft Alan Sparhawk on Jeff’s Production Holly Herndon AI + Choir + Process Ryan Bingham Crazy Heart, Acting, Singing Avedis Kifedjian of Avedis Audio in Behind the Gear Dave Cook King Crimson, Amy Helm, Ravi Shankar Mitch Dane Sputnik Sound, Jars of Clay, Nashville Gear Reviews $5.99 No. 132 Aug/Sept 2019 christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu christy (at) miracosta (dot) edu Hello and welcome to Tape Op 10 Letters 14 Holly Herndon 20 Jeff Tweedy 32 Tom Schick # 40 Spencer Tweedy 44 Gear Reviews ! 66 Larry’s End Rant 132 70 Behind the Gear with Avedis Kifedjian 74 Mitch Dane 77 Dave Cook Extra special thanks to Zoran Orlic for providing more 80 Ryan Bingham amazing photos from The Loft than we could possibly run. Here’s one more of Jeff Tweedy and Nels Cline talking shop. 83 page Bonus Gear Reviews Interview with Jeff starts on page 20. <www.zoranorlic.com> “How do we stay interested in the art of recording?” It’s a question I was considering recently, and I feel fortunate that I remain excited about mixing songs, producing records, running a studio, interviewing recordists, and editing this magazine after twenty-plus years. But how do I keep a positive outlook on something that has consumed a fair chunk of my life, and continues to take up so much of my time? I believe my brain loves the intersection of art, craft, and technology. -

“Jewish Problem”: Othering the Jews and Homogenizing Europe

NOTES Introduction 1. Dominick LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz (Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press, 1998), 26. 2. Lyotard, Jean Francois, Heidegger and “the jews,” trans. Andreas Michel and Mark S. Roberts (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990). 3. Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless (New York: Grove Press, 1988). 4. Charles Maier, The Unmasterable Past, History, Holocaust and German National Identity (Harvard University Press, 1988), 1. 5. See Maurizio Passerin d’Entrèves and Seyla Benhabib, eds., Habermas and the Unfinished Project of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1996). 6. LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz, 22, note 14. 7. Ibid., 41. 8. Ibid., 40–41. 9. Jeffrey Alexander et al., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004). 10. Idith Zertal, Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, trans. Chaya Galai, Cambridge Middle East Studies 21 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 4. 11. Angi Buettner, “Animal Holocausts,” Cultural Studies Review 8.1 (2002): 28. 12. Angi Buettner, Haunted Images: The Aesthetics of Catastrophe in a Post-Holocaust World (PhD diss., University of Queensland, 2005), 139. 13. Ibid, 139. 14. Ibid., 157. 15. Ibid., 159–160. 16. Ibid., 219. 17. Tim Cole, Selling the Holocaust: From Auschwitz to Schindler, How History Is Bought, Packaged and Sold (New York: Routledge, 1999). 18. LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz, 21. Chapter One Producing the “Jewish Problem”: Othering the Jews and Homogenizing Europe 1. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, “Exile and Expulsion in Jewish History,” in Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World 1391–1648, ed.