Liberian Studies Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

A Short History of the First Liberian Republic

Joseph Saye Guannu A Short History of the First Liberian Republic Third edition Star*Books Contents Preface viii About the author x The new state and its government Introduction The Declaration of Independence and Constitution Causes leading to the Declaration of Independence The Constitutional Convention The Constitution The kind of state and system of government 4 The kind of state Organization of government System of government The l1ag and seal of Liberia The exclusion and inclusion of ethnic Liberians The rulers and their administrations 10 Joseph Jenkins Roberts Stephen Allen Benson Daniel Bashiel Warner James Spriggs Payne Edward James Roye James Skirving Smith Anthony William Gardner Alfred Francis Russell Hilary Richard Wright Johnson JosephJames Cheeseman William David Coleman Garretson Wilmot Gibson Arthur Barclay Daniel Edward Howard Charles Dunbar Burgess King Edwin James Barclay William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman William Richard Tolbert PresidentiaI succession in Liberian history 36 BeforeRoye After Roye iii A Short HIstory 01 the First lIberlJn Republlc The expansion of presidential powers 36 The socio-political factors The economic factors Abrief history of party politics 31 Before the True Whig Party The True Whig Party Interior policy of the True Whig Party Major oppositions to the True Whig Party The Election of 1927 The Election of 1951 The Election of 1955 The plot that failed Questions Activities 2 Territorial expansion of, and encroachment on, Liberia 4~ Introduction 41 Two major reasons for expansion 4' Economic -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Taylor Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR THURSDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 2010 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Julia Sebutinde, Presiding Justice Richard Lussick Justice Teresa Doherty Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Ms Erica Bussey For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Ms Zainab Fofanah For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Nicholas Koumjian Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Morris Anyah Mr Simon Chapman CHARLES TAYLOR Page 35995 25 FEBRUARY 2010 OPEN SESSION 1 Thursday, 25 February 2010 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:29:10 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We will take appearances, 6 please. 7 MR KOUMJIAN: Good morning, Madam President, your Honours, 8 counsel opposite. For the Prosecution this morning, Brenda J 9 Hollis, Maja Dimitrova and myself Nicolas Koumjian. 09:33:35 10 MR ANYAH: Good morning, Madam President. Good morning, 11 your Honours. Good morning, counsel opposite. Appearing for the 12 Defence this morning are Courtenay Griffiths QC and myself Morris 13 Anyah. Thank you. 14 MR GRIFFITHS: Madam President, can I raise a matter which 09:33:49 15 was brought to my notice by the Court Manager this morning. 16 Apparently Mr Taylor doesn't have access to LiveNote at the 17 moment. That really concerns me, because from our point of view 18 it's imperative that the defendant, of all people in this 19 courtroom, be able to follow the proceedings. -

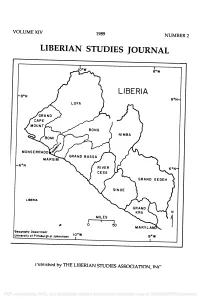

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

2008 National Population and Housing Census: Preliminary Results

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA 2008 NATIONAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS: PRELIMINARY RESULTS LIBERIA INSTITUTE OF STATISTICS AND GEO-INFORMATION SERVICES (LISGIS) MONROVIA, LIBERIA JUNE 2008 FOREWORD Post-war socio-economic planning and development of our nation is a pressing concern to my Government and its development partners. Such an onerous undertaking cannot be actualised with scanty, outdated and deficient databases. Realising this limitation, and in accordance with Article 39 of the 1986 Constitution of the Republic of Liberia, I approved, on May 31, 2007, “An Act Authorizing the Executive Branch of Government to Conduct the National Census of the Republic of Liberia”. The country currently finds itself at the crossroads of a major rehabilitation and reconstruction. Virtually every aspect of life has become an emergency and in resource allocation, crucial decisions have to be taken in a carefully planned and sequenced manner. The publication of the Preliminary Results of the 2008 National Population and Housing Census and its associated National Sampling Frame (NSF) are a key milestone in our quest towards rebuilding this country. Development planning, using the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), decentralisation and other government initiatives, will now proceed into charted waters and Government’s scarce resources can be better targeted and utilized to produce expected dividends in priority sectors based on informed judgment. We note that the statistics are not final and that the Final Report of the 2008 Population and Housing Census will require quite sometime to be compiled. In the interim, I recommend that these provisional statistics be used in all development planning for and in the Republic of Liberia. -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME VI 1975 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL (-011111Insea.,.... , .. o r r AFA A _ 2?-. FOR SALE 0.1+* CHARLIE No 4 PO ßox 419, MECNttt+ ST tR il LIBERIA C MONROVIA S.. ) J;1 MMNNIIN. il4j 1 Edited by: Svend E. Holsoe, Frederick D. McEvoy, University of Delaware Marshall University PUBLISHED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor African Art Stores, Monrovia. (Photo: Jane J. Martin) PDF compression, OCR, web optimizationi using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME VI 1975 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL EDITED BY Svend E. Holsoe Frederick D. McEvoy University of Delaware Marshall University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Igolima T. D. Amachree Western Illinois University J. Bernard Blamo Mary Antoinette Brown Sherman College of Liberal & Fine Arts William V. S. Tubman Teachers College University of Liberia University of Liberia George E. Brooks, Jr. Warren L. d'Azevedo Indiana University University of Nevada David Dalby Bohumil Holas School of Oriental and African Studies Centre des Science Humaines University of London Republique de Côte d'Ivoire James L. Gibbs, Jr. J. Gus Liebenow Stanford University Indiana University Bai T. Moore Ministry of Information, Cultural Affairs & Tourism Republic of Liberia Published at the Department of Anthropology, University of Delaware James E. Williams Business Manager PDFb compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS page THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE STATE OF AGRICULTURE AND COMMERCE, by M. B. Akpan 1 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF KRU POWER: FERNANDO PO IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, by Ibrahim K. -

There Are Two Systems of Surveillance Operating in Burundi at Present

LIVELIHOOD ZONING ACTIVITY IN LIBERIA - UPDATE A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM NETWORK (FEWS NET) May 2017 1 LIVELIHOOD ZONING ACTIVITY IN LIBERIA - UPDATE A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM NETWORK (FEWS NET) April 2017 This publication was prepared by Stephen Browne and Amadou Diop for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), in collaboration with the Liberian Ministry of Agriculture, USAID Liberia, WFP, and FAO. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Page 2 of 60 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................................... 5 Background and Introduction......................................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 8 National Livelihood Zone Map .......................................................................................................12 National Seasonal Calendar ..........................................................................................................13 Timeline of Shocks and Hazards ....................................................................................................14 -

Seasons in Hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Phillip James, "Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3905. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SEASONS IN HELL: CHARLES S. JOHNSON AND THE 1930 LIBERIAN LABOR CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Phillip James Johnson B. A., University of New Orleans, 1993 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1995 May 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt of gratitude goes to my wife, Ava Daniel-Johnson, who gave me encouragement through the most difficult of times. The same can be said of my mother, Donna M. Johnson, whose support and understanding over the years no amount of thanks could compensate. The patience, wisdom, and good humor of David H. Culbert, my dissertation adviser, helped enormously during the completion of this project; any student would be wise to follow his example of professionalism. -

LIBERIA. -A Republic Founded by Black Men, Reared by Black Men, Maintained by Black Men, and Which Holds out to Our Hope the Brightest Prospects.—H Enry C L a Y

LIBERIA. -A republic founded by black men, reared by black men, maintained by black men, and which holds out to our hope the brightest prospects.—H enry C l a y . ./ BULLETIN No. 33. NOVEMBER, 19' ISSUED BY THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION ... ~ * *.^ Ui?un/ri5 c o x t k n t s . V £ REV. DR. ALEXANDER PRIESTLY CAMPHOR..............................Frontispiece PRESIDENT ARTHUR BARCLAY'S MESSAGE................. I LIBERIAN ENVOYS RECEIVED AT THE EXECUTIVE MANSION.... 14 THE LIBERIAN COMMISSION.............................................................................. 18 REMARKS OP H. R. p . THE PRINCE OF WALES.....................T 22 REMARKS OF THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL.OF CREWE, K. G 24 OUR LIBERIAN ENVOYS MEET PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT.................. 28 ,EX-PRESIDENT WILLIAM DAVID COLEMAN DEAD..-....................... f .. 30 ■JBERIA AND THE FOREIGN POWERS................................................. 33 LMPOSIUM OF NEWS FROM AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS ON L^ERIAN ENVOYS............................................... 37 PRESIDENT TO NEGRO—EQUAL OPPORTUNITY FOR WHITE AND BLACK RACES................ 39 THE RETURN-OF LIBERIA’S BIRTHDAY ......... 47 DR. BOOKER T. WASHINGTON WRITES OF RECEPTION IN WASH INGTON AND ELSEWHERE—THE UNITED STATES A FRIEND’ .49 BLIND TO M ........ ....................................... 52 THE THREE NEEDS OF LIBERIA.....................Dr. Edward W. Bi<yden 54 ITEMS ............................ 57 WASHINGTON, D. C. COLONIZATION BUILDING, 460 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE. THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY. I'UE^IDEXT: 1907 Rev. SAMUEL E. APPLETON,D. D,, Pa. 1 'ICE-PR RSJDEN TS : k 1876 Rev. Bishop H. M. Turner, D. D., 6a., 1896 Rev. Bishop J. A. Handy, D. J)., Fla. ■ 1881 Rev. Bishop H. W. g ir re n , D. D., Col. 1896 Mr. George A. Pope, Md. W 881 Prof. Edw. W.BJyden, LL.D., Liberia. 1896 Rev. -

Modern African Leaders

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 012 SO 032 175 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, CherieD., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People ofInterest to Young Readers. World Leaders Series: Modern AfricanLeaders. Volume 2. ISBN ISBN-0-7808-0015-X PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 223p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., 615 Griswold, Detroit,MI 48226; Tel: 800-234-1340; Web site: http: / /www.omnigraphics.com /. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020)-- Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African History; Biographies; DevelopingNations; Foreign Countries; *Individual Characteristics;Information Sources; Intermediate Grades; *Leaders; Readability;Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Africans; *Biodata ABSTRACT This book provides biographical profilesof 16 leaders of modern Africa of interest to readersages 9 and above and was created to appeal to young readers in a format theycan enjoy reading and easily understand. Biographies were prepared afterextensive research, and this volume contains a name index, a general index, a place of birth index, anda birthday index. Each entry providesat least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead thereader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, firstjobs, marriage and family,career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies,and honors and awards. All of the entries end with a list of highly accessiblesources designed to lead the student to further reading on the individual.African leaders featured in the book are: Mohammed Farah Aidid (Obituary)(1930?-1996); Idi Amin (1925?-); Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1898?-); HaileSelassie (1892-1975); Hassan II (1929-); Kenneth Kaunda (1924-); JomoKenyatta (1891?-1978); Winnie Mandela (1934-); Mobutu Sese Seko (1930-); RobertMugabe (1924-); Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972); Julius Kambarage Nyerere (1922-);Anwar Sadat (1918-1981); Jonas Savimbi (1934-); Leopold Sedar Senghor(1906-); and William V. -

FED FY4 Q2 Report January-March 2015

FOO D AND ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT (FED) PROGRAM FOR LIBERIA QUARTERLY REPORT: JANUARY-MARCH 2015 Contract Number: 669-C-00-11-00047-00 0 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Development Alternatives Incorporated. Contractor: DAI Program Title: Food and Enterprise Development Program for Liberia (FED) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Liberia Contract Number: 669-00-11-00047-00 Date of Publication: April 15, 2015 Photo Caption: USAID FED-supported Zeelie Farmers Association engaging in aggregation and trading, with its paddy rice purchased through a loan from the LEAD microfinance. DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID Food and Enterprise Development Program for Liberia Quarterly Report, Q2 FY 2015 Acronyms AEDE Agency for Economic Development and Empowerment APDRA Association Pisciculture et Development Rural en Afrique AVTP Accelerated Vocational Training Program AYP Advancing Youth Project BSTVSE Bureau of Science, Technical, Vocational and Special Education BWI Booker Washington Institute CARI Center of Agriculture Research Institute CAHW Community Animal Health Worker CBF County Based Facilitator CBL Central Bank of Liberia CILSS Permanent Interstates Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel CoE Center of Excellence CYNP Community Youth Network Program DAI Development Alternatives Inc. DCOP Deputy Chief