Liberian Studies Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transversal Politics and West African Security

Transversal Politics and West African Security By Moya Collett A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences and International Studies University of New South Wales, 2008 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed Moya Collett…………….............. Date 08/08/08……………………….............. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

A Short History of the First Liberian Republic

Joseph Saye Guannu A Short History of the First Liberian Republic Third edition Star*Books Contents Preface viii About the author x The new state and its government Introduction The Declaration of Independence and Constitution Causes leading to the Declaration of Independence The Constitutional Convention The Constitution The kind of state and system of government 4 The kind of state Organization of government System of government The l1ag and seal of Liberia The exclusion and inclusion of ethnic Liberians The rulers and their administrations 10 Joseph Jenkins Roberts Stephen Allen Benson Daniel Bashiel Warner James Spriggs Payne Edward James Roye James Skirving Smith Anthony William Gardner Alfred Francis Russell Hilary Richard Wright Johnson JosephJames Cheeseman William David Coleman Garretson Wilmot Gibson Arthur Barclay Daniel Edward Howard Charles Dunbar Burgess King Edwin James Barclay William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman William Richard Tolbert PresidentiaI succession in Liberian history 36 BeforeRoye After Roye iii A Short HIstory 01 the First lIberlJn Republlc The expansion of presidential powers 36 The socio-political factors The economic factors Abrief history of party politics 31 Before the True Whig Party The True Whig Party Interior policy of the True Whig Party Major oppositions to the True Whig Party The Election of 1927 The Election of 1951 The Election of 1955 The plot that failed Questions Activities 2 Territorial expansion of, and encroachment on, Liberia 4~ Introduction 41 Two major reasons for expansion 4' Economic -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XVI 1991 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL 1 1 0°W 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6 °N RIVER I 6 °N- 1 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department ION/ 8 °W 1 University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XVI 1991 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Alfred B. Konuwa Butte College EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS ABOUT LANDSELL K. CHRISTIE, THE LIBERIAN IRON ORE INDUSTRY AND SOME RELATED PEOPLE AND EVENTS: GETTING THERE 1 by Garland R. Farmer ZO MUSA, FONINGAMA, AND THE FOUNDING OF MUSADU IN THE ORAL TRADITION OF THE KONYAKA .......................... 27 by Tim Geysbeek and Jobba K. Kamara CUTTINGTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DURING THE LIBERIAN CIVIL WAR: AN ADMINISTRATOR'S EXPERIENCE ............ -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Seasons in Hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis Phillip James Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Phillip James, "Seasons in hell: Charles S. Johnson and the 1930 Liberian Labor Crisis" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3905. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SEASONS IN HELL: CHARLES S. JOHNSON AND THE 1930 LIBERIAN LABOR CRISIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Phillip James Johnson B. A., University of New Orleans, 1993 M. A., University of New Orleans, 1995 May 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt of gratitude goes to my wife, Ava Daniel-Johnson, who gave me encouragement through the most difficult of times. The same can be said of my mother, Donna M. Johnson, whose support and understanding over the years no amount of thanks could compensate. The patience, wisdom, and good humor of David H. Culbert, my dissertation adviser, helped enormously during the completion of this project; any student would be wise to follow his example of professionalism. -

LIBERIA. -A Republic Founded by Black Men, Reared by Black Men, Maintained by Black Men, and Which Holds out to Our Hope the Brightest Prospects.—H Enry C L a Y

LIBERIA. -A republic founded by black men, reared by black men, maintained by black men, and which holds out to our hope the brightest prospects.—H enry C l a y . ./ BULLETIN No. 33. NOVEMBER, 19' ISSUED BY THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION ... ~ * *.^ Ui?un/ri5 c o x t k n t s . V £ REV. DR. ALEXANDER PRIESTLY CAMPHOR..............................Frontispiece PRESIDENT ARTHUR BARCLAY'S MESSAGE................. I LIBERIAN ENVOYS RECEIVED AT THE EXECUTIVE MANSION.... 14 THE LIBERIAN COMMISSION.............................................................................. 18 REMARKS OP H. R. p . THE PRINCE OF WALES.....................T 22 REMARKS OF THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL.OF CREWE, K. G 24 OUR LIBERIAN ENVOYS MEET PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT.................. 28 ,EX-PRESIDENT WILLIAM DAVID COLEMAN DEAD..-....................... f .. 30 ■JBERIA AND THE FOREIGN POWERS................................................. 33 LMPOSIUM OF NEWS FROM AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS ON L^ERIAN ENVOYS............................................... 37 PRESIDENT TO NEGRO—EQUAL OPPORTUNITY FOR WHITE AND BLACK RACES................ 39 THE RETURN-OF LIBERIA’S BIRTHDAY ......... 47 DR. BOOKER T. WASHINGTON WRITES OF RECEPTION IN WASH INGTON AND ELSEWHERE—THE UNITED STATES A FRIEND’ .49 BLIND TO M ........ ....................................... 52 THE THREE NEEDS OF LIBERIA.....................Dr. Edward W. Bi<yden 54 ITEMS ............................ 57 WASHINGTON, D. C. COLONIZATION BUILDING, 460 PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE. THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY. I'UE^IDEXT: 1907 Rev. SAMUEL E. APPLETON,D. D,, Pa. 1 'ICE-PR RSJDEN TS : k 1876 Rev. Bishop H. M. Turner, D. D., 6a., 1896 Rev. Bishop J. A. Handy, D. J)., Fla. ■ 1881 Rev. Bishop H. W. g ir re n , D. D., Col. 1896 Mr. George A. Pope, Md. W 881 Prof. Edw. W.BJyden, LL.D., Liberia. 1896 Rev. -

Questionnaire Liberia

Questionnaire Liberia Foreword by Researcher I deemed it practical to give a short introduction on the Liberian Judicial System as well as its constitutional framework by pointing out a few historical, structural and legal specialities. Due to its historical background1, political and military disruptions and years of civil war, the formal Liberian justice system is markedly weak. The discrepancy between the law on the books and the law in action is probably more distinct than in many other countries of West-Africa (especially Ghana and Nigeria), as the formal judicial system earns only a minimum of trust amongst the population of Liberia. A study by the United States Peace Institute2 revealed that in civil disputes of a total of 3181 cases, 59% are not taken to any forum for resolving the issue, 38% of the cases are taken to the informal /customary forum and only 3% of the civil disputes (2% of criminal disputes) are taken to the formal judicial forum of Magistrate Courts at the lowest instance. According to the International Development Law Organisation3, out of 320 Magistrate Judges, 30 can offer some kind of judicial training. Financial shortages make it extremely difficult to train judicial officers. The Judicial Training Institute (JTI) of Liberia explained that almost the entire salaries of the judiciary are paid by external donors (in the past mainly by the American Bar Association). The JTI was to a large extend financed by the GIZ, whose Programme in Liberia was terminated at the end of 2013. Most stakeholders are aware that revision and reform processes need to be expedited but they are still moving rather moderately. -

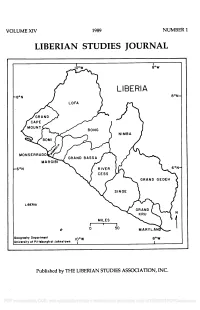

Volume Xiv 1989 Number 1 Liberian Studies Journal -8

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL I 10 °W 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6°N RIVER 6°N- MILES I I 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department °W 10 8°W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 1 I Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. El wood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Joseph S. Guannu Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN REFINERY, A LOOK INSIDE A PARTIALLY "OPEN DOOR" ....................................................... 1 by Garland R. Farmer HARVEY S. FIRESTONE'S LIBERIAN INVESTMENT: 1922 -1932 .. 13 by Arthur J. Knoll LIBERIA AND ISRAEL: THE EVOLUTION OF A RELATIONSHIP 34 by Yekutiel Gershoni THE KRU COAST REVOLT OF 1915 -1916 ........................................... 51 by Jo Sullivan EUROPEAN INTERVENTION IN LIBERIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE "CADELL INCIDENT" OF 1908 -1909 . -

Africa and Liberia in World Politics

© COPYRIGHT by Chandra Dunn 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AFRICA AND LIBERIA IN WORLD POLITICS BY Chandra Dunn ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes Liberia’s puzzling shift from a reflexive allegiance to the United States (US) to a more autonomous, anti-colonial, and Africanist foreign policy during the early years of the Tolbert administration (1971-1975) with a focus on the role played by public rhetoric in shaping conceptions of the world which engendered the new policy. For the overarching purpose of understanding the Tolbert-era foreign-policy actions, this study traces the use of the discursive resources Africa and Liberia in three foreign policy debates: 1) the Hinterland Policy (1900-05), 2) the creation of the Organization for African Unity (OAU) (1957- 1963), and finally, 3) the Tolbert administration’s autonomous, anti-colonial foreign policy (1971-1975). The specifications of Liberia and Africa in the earlier debates are available for use in subsequent debates and ultimately play a role in the adoption of the more autonomous and anti-colonial foreign policy. Special attention is given to the legitimation process, that is, the regular and repeated way in which justifications are given for pursuing policy actions, in public discourse in the United States, Europe, Africa, and Liberia. The analysis highlights how political opponents’ justificatory arguments and rhetorical deployments drew on publicly available powerful discursive resources and in doing so attempted to define Liberia often in relation to Africa to allow for certain courses of action while prohibiting others. Political actors claimed Liberia’s membership to the purported supranational cultural community of Africa. -

Post-Emancipation Barbadian Emigrants in Pursuit Of

“MORE AUSPICIOUS SHORES”: POST-EMANCIPATION BARBADIAN EMIGRANTS IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONHOOD IN LIBERIA, 1834 – 1912 By Caree A. Banton Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Richard Blackett Professor Jane Landers Professor Moses Ochonu Professor Jemima Pierre To all those who labored for my learning, especially my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to more people than there is space available for adequate acknowledgement. I would like to thank Vanderbilt University, the Albert Gordon Foundation, the Rotary International, and the Andrew Mellon Foundation for all of their support that facilitated the research and work necessary to complete this project. My appreciation also goes to my supervisor, Professor Richard Blackett for the time he spent in directing, guiding, reading, editing my work. At times, it tested his patience, sanity, and will to live. But he persevered. I thank him for his words of caution, advice and for being a role model through his research and scholarship. His generosity and kind spirit has not only shaped my academic pursuits but also my life outside the walls of the academy. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of my dissertation committee: Jane Landers, Moses Ochonu, and Jemima Pierre. They have provided advice and support above and beyond what was required of them. I am truly grateful not only for all their services rendered but also the kind words and warm smiles with which they have always greeted me. -

Military and Civilian Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Comparative Analysis of Public Policy Outputs and Outcomes

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Military and Civilian Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Analysis of Public Policy Outputs and Outcomes. Iren Omo-bare Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Omo-bare, Iren, "Military and Civilian Regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Analysis of Public Policy Outputs and Outcomes." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5085. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5085 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Open Door Policy of Liberia

VEROFFENTLICHUNGEN AUS DEM UBERSEE-MUSEUM BREMEN Reihe F Bremer Afrika Archiv Band 17/2 Bremen 1983 Im Selbstverlag des Museums The Open Door Policy of Liberia An Economic History of Modern Liberia R R M. van der Kraaij CONTENTS VOLUME II List of Annexes ii Footnotes 4-61 Introduction 4-61 Chapter 1 . .4-62 Chapter 2 ........ .4-65 Chapter 3 ........ .4-72 Chapter 4- ........ .4-78 Chapter 5 .4-83 Chapter 6 . .4-86 Chapter 7 492 Chapter 8 500 Chapter 9 ........ .509 Chapter 10 ........ .513 Chapter 11 '. .518 Chapter 12 ........ .522 Chapter 13 .528 Annexes 531 Bibliography 662 Curriculum Vitae 703 Index 704. ii LIST OF ANNEXES Page 1 One of the gaps in Liberian History: President Roye's death and his succession 531 2 The Open Door: The question of immigration 533 3 Statement of the public debt 1914-1926 536 4 Public Debt as at August 31, 1926 537 5 Letter dated July 12, 1971 from L. Kwia Johnson, Acting Secretary of the Treasury to A.G. Lund, President, Firestone Plantations Company 538 6 Letter dated October 7, 1969 from W. Edward Greaves, Under Secretary for Revenues to R.F. Dempster, Comptroller, Firestone Plantations Company 539 7 The Planting Agreement of 1926 with amendments of 1935", 1936, 1937, 1939, 1950, 1951, 1953, 1959, 1962 and 1965. 540 8 Summary Table of renegotiation of the 1926 Planting Agreement with Firestone 1974 - 1975 - 1976 551 9 A comparison of four gold and/or diamond mining concession agreements 567 10 The "Columbia Southern Chemical Corporation" concession agreement (1956) and the "Liberian Beach Sands Exploitation Company" mining con- cession agreement (1973).